Birmingham, Warwickshire

Up to 1834

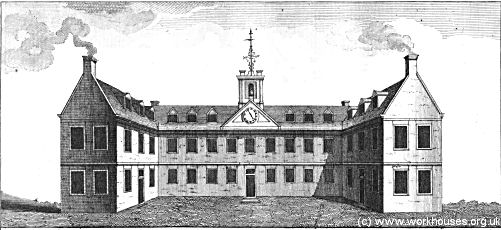

On 3rd April 1734, a meeting was held and orders given for the purchasing of a site and building of a workhouse for the parish of Birmingham (Dent, 1893). The workhouse was erected soon afterwards on land between Lichfield Street and Steelhouse Lane, where Coleridge Passage now stands. The building cost £1,173 and was intended to accommodate 600. Later extensions included an infirmary wing at the left erected in 1766 at a cost of £400, and a workshop wing at the right erected in 1779 at a cost of £1,100.

Birmingham parish workhouse, mid-1700s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1783, Birmingham was incorporated under a local Act of Parliament, giving it greater powers over the management of poor relief. The Incorporation was managed by a body of 108 Guardians of the Poor and was enabled to set up a workhouse "with Apartments for the sick and diseased, and for the old, impotent and infirm, and for those able to work, for the carrying on divers Trades, Works, and Manufactures, as also for the Punishment of the idle, refractory, and profligate". In fact, the Incorporation appears to have continued using the existing parish workhouse building for a further 70 years. By 1848, it could accommodate 645 inmates and was generally full.

Part of Birmingham's 1783 Local Act of Incorporation.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1789, Josiah Robins, a worsted maker in Digbeth, was given permission to set up a workshop in premises adjoining the workhouse, and to employ the inmates. Their earnings were paid each week to the workhouse governor. Some inmates, who were deemed capable, were appointed as instructors and supervisors and given separate accommodation at the workhouse.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, reported of Birmingham that:

| BIRTHS. | DEATHS. | ||||||||||

| Year. | Av.No.in house. | Boys. | Girls. | T'l. | Men. | Women. | Boys. | Girls. | T'l. | ||

| 1791 | 350 | 24 | 20 | 44 | 58 | 51 | 12 | 7 | 128 | ||

| 1792 | 400 | 25 | 18 | 43 | 62 | 55 | 12 | 7 | 136 | ||

| 1793 | 470 | 20 | 15 | 35 | 28 | 39 | 14 | 12 | 93 | ||

| 1794 | 640 | 43 | 20 | 63 | 41 | 57 | 40 | 24 | 162 | ||

| 1795 | 500 | 25 | 36 | 61 | 28 | 57 | 18 | 18 | 121 | ||

| 1796 to Sept. 2. | 464 | 25 | 16 | 41 | 27 | 39 | 8 | 8 | 82 | ||

From around 1812, during a national shortage of coins, Birmingham was one of several workhouses to issue workhouse tokens — specially minted coins given as poor relief. Local shopkeepers could then redeem the tokens at the workhouse. This example, from 1812, features a picture of the Incorporation workhouse, and the wording "ONE POUND NOTE PAYABLE AT THE WORKHOUSE FOR 240 TOKENS".

Birmingham workhouse token.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Plans were regularly being devised to try and keep the poor rates down. In 1754, the spinning of packthread was introduced into the workhouse. In 1756, a mill for grinding corn was set up in the house, but was sold in 1761. In 1766, the spinning of mop yarn was introduced, but the yarn proved of less value than the wool. Various other plans were tried, but all failed, and the rates kept advancing — from £661 in 1700, to £12,045 in 1792, £61,928 in 1818, and £37,586 in the half year ending Lady-day, 1848. Birmingham's population rose from 15,032 in 1700, to 73,653 in 1791, and to around 170,000 in 1848. In other words, between 1700 and 1848 the population rose nearly elevenfold, but over the same period the poor rate rose more than 135 times in amount.

The Asylum for the Infant Poor

In 1797, an "Asylum for the Infant Poor" was opened an Asylum Road, at the east side of Summer Lane. William Hutton's 1836 History of Birmingham records that:

The Asylum closed in around 1852.

After 1834

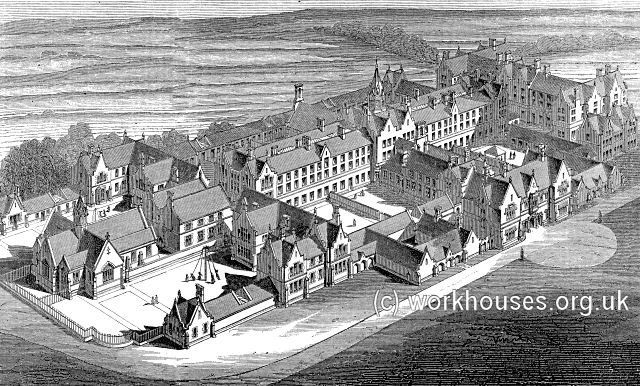

Birmingham's Local Act status made it exempt from most of the provisions of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act and the Incorporation remained in operation, continuing to use the Lichfield Street workhouse. Finally, in the late 1840s, it was decided that a new workhouse was needed. The design of the new building was the subject of competitions in 1848 and 1849, with the eventual winning plans being submitted by JJ Bateman. The foundation stone of the new building was laid on 9th September 1850 on a site at the junction of Dudley Road and Western Road at Winson Green. The building was opened on 9th March 1852. An architect's "bird's-eye view" of the site shows its layout.

Birmingham bird's-eye view from the south, 1852.

A contemporary report describes the main features of the building.

The cooking for the whole of the establishment is performed in one central kitchen. One entrance only is provided to the buildings for the better control of ingress and egress to and from the establishment.

The main building, comprising the workhouse department, has an open corridor throughout, 10 feet wide, and open from the second floor to the roof, with iron galleries at each floor, for supervision by the officers only. This arrangement gives great facility for effective ventilation, and inspection.

The chapel is fitted up with open seats, and two small galleries in the transepts for children.

By private subscription of the guardians, the officers of the workhouse, and the contractors, three stained glass windows (by Messrs. Chance), from Winchester examples, have been placed in the chancel and aisles. The chancel window contains, in the five principal lights, figures of the Saviour and four Evangelists, with canopies and pedestals, and symbols in the ten upper lights. The two aisle windows contain four scriptural subjects of almsgiving. Two other one-light windows have been presented by Messrs. Chance, of the Baptism and Preaching of St. John. The remaining aisle and transept windows have been filled with stained flower quarries by the architect. Mr. Minton has presented encaustic tiles for the chancel, and the architect has given Minton's tiles for the aisles and nave.

The whole of the building works have been very creditably performed by Mr. Glenn, of Liverpool-road, London.

The cold water is supplied from a well by an engine to a tank, containing 30,000 gallons, placed above the ridges of the building, and a reserve of 10,000 gallons from the ordinary supply is always retained in the tank for the supply of the fire-mains, which extend throughout the buildings. The drains are flushed from this tank.

From a high-pressure steam-boiler, placed in a central situation, hot supplies for baths, lavatories, hospital, wash-house, drying-house, kitchen, sculleries, and for warming the infirm wards, dining-hall, and other parts of the building, are obtained. The engineering work has been ably constructed and applied by Mr. W. Jeakes, of London, and the comprehensive centralization of the heating powers has been very successfully carried out. Every room will be lighted by gas.

The furniture, of design to correspond with the building, has been made by Messrs. Jenkins and Ashford, of Birmingham.

The arrangements for ventilation, and other sanitary provisions, have been well spoken of. The buildings include an area of above five acres, and liberal accommodation is provided for 1,610 inmates. The cost of the building amounts to about 29,000l., exclusive of fixtures, furniture and fittings.

The layout of the building is shown on the plan below.

Birmingham workhouse plan, 1852.

Birmingham workhouse entrance, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse entrance block from the north-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse entrance from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse entrance block from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse chapel interior, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Various additions were made to the buildings. By 1885, a T-shaped school block for boys had been erected at the north of the workhouse, with a corresponding one for girls to the south.

Birmingham workhouse boys' school block from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1888, a large infirmary designed by WH Ward of Birmingham was erected at the west of the workhouse. The layout of the site in 1890 is shown on the map below.

Birmingham map, 1890.

An architect's bird's-eye view of the buildings was published in 1888.

Birmingham workhouse infirmary from the south-east, 1888.

Birmingham workhouse infirmary from the south-west, 1930s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse infirmary Blocks 4 and 6 from the north-east, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse infirmary block from the north-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham workhouse maternity block, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the winters of 1878-79 and 1879-80, a stoneyard was opened to serve as a labour test for men being given out-relief. However, little work was performed by many of the applicants and the scheme only succeeded in attracting the able-bodied poor of neighbouring districts. The Guardians then took over a large disused factory in which they set up a temporary branch workhouse for the able-bodied. A mixture of spartan conditions and a requirement for hard labour proved so effective in deterring applicants that a permanent Test House was erected at the north-west of the main workhouse site, separate from the main establishment. The work required of inmates included oakum-picking — the daily amounts demanded being 4lb for men and 3lb. for women. This compared somewhat unfavourably with the amounts required of prisoners serving terms of hard labour of 3½lb. and 2lb. respectively. Sleeping accommodation in the Test House comprised a continuous sloping shelf on which inmates had to lie together. The Test House continued in operation until 1889 at which time the numbers of inmates had fallen so low as to warrant its closure.

Birmingham workhouse former Test House, 2007.

© Peter Higginbotham.

On 11th November, 1893, a touching workhouse romance was revealed in a letter from an inmate of the workhouse to the master, Mr Mitchell, and the guardians. Literally transcribed, the missive ran:

We remain your Humble Servants. Thomas Hughes 80 Emma Llewllen 63.

By the early 1900s, a separate "male merit" ward had been established to provide more comfortable conditions for older inmates judged to be of good character. Presumably, one was also set up for the women.

Birmingham workhouse male merit ward, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 1 Western Road, Birmingham.

In 1911, Birmingham merged the adjacent Aston and King's Norton unions to form enlarged Birmingham Poor Law union. The Birmingham workhouse site later became Dudley Road Hospital. Almost all of the original workhouse buildings have now been demolished.

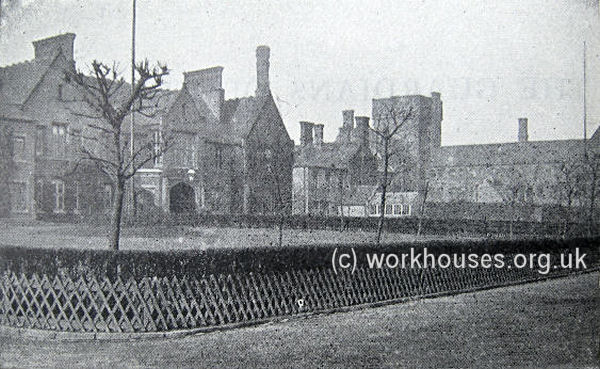

Birmingham workhouse site from the west, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

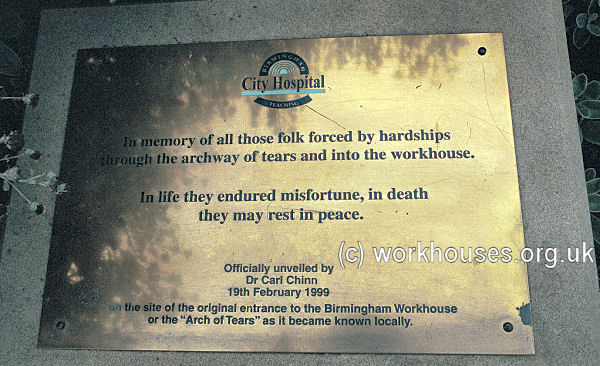

Birmingham workhouse memorial plaque, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green Cottage Homes

The Marston Green Cottage Homes were erected in 1878-9 to provide accommodation for pauper children aged from three upwards. The Marston Green site was one the earliest such developments to be organised as a "village" located away from the workhouse in an airy rural setting. The original scheme, which opened in January 1880, included seven homes for boys and seven for girls, together with a probationary home, school, infirmary, swimming baths, workshops, bakehouse, a superintendent's house and offices. A farm was built to the south of the homes. The site layout is shown on the 1904 map below:

Marston Green Cottage Homes site, 1904.

Birmingham Marston Green children's home, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham Marston Green children's home, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham Marston Green children's home (detail), c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Each cottage was under the care of foster parents and could house around 30 boys or girls, giving accommodation for a total of 420 children.

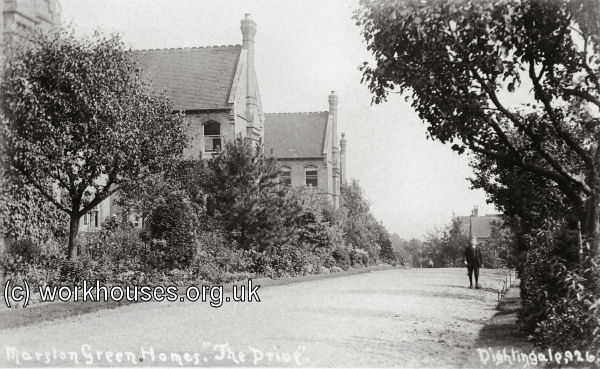

Marston Green cottage homes, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes resident, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes - a dining room, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes - a dining room (detail), c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

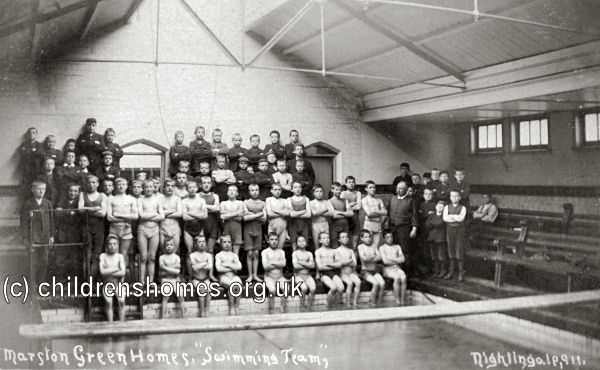

Marston Green cottage homes - swimming team, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green cottage homes - swimming team (detail), c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green children's house from the south-west, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A porter's lodge was added at the site entrance in 1881.

Marston Green Entrance lodge from the south-east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green Entrance lodge from the south, c.1921.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A board at the entrance noted that visits to children were permitted between 2pm and 4pm on the first Wednesday in the months of January, March, May, July, September and November.

Marston Green Cottage Homes notice board, c.1921.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A laundry was built in 1899, then in 1905 two further children's houses were added, together with a 500-seat chapel located at the north-west of the lodge.

Marston Green homes and chapel under construction from the west, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Marston Green chapel from the south-east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

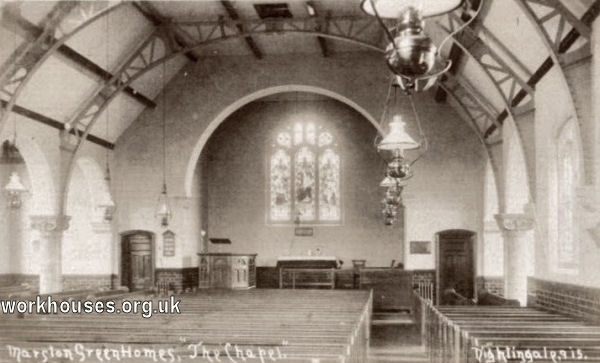

Marston Green chapel interior, early 1900s.

After 1911, the age limit for admission was lowered to two, and two new cottages for infants were erected giving a total capacity of 510 children. Other additions included a convalescent home (Ivy Lodge) in 1913, and an assembly hall and new swimming bath in 1923.

Boys at the homes learnt various trades, and the girls household work. A chaplain attended the homes regularly to give instruction and to conduct religious services.

After 1930, the site became Coleshill Mental Hospital, caring for what were then referred to as mental defectives. The remaining children children were then either boarded out with families, or transferred to either the Aston Cottage Homes at Erdington, or the King's Norton Cottage Homes at Shenley Fields.

The site was later renamed Chelmsley Hospital. Most of the cottage homes buildings have now been demolished and replaced by modern housing. Only the lodge, chapel, mortuary, and two houses survive, now converted to business use.

Jenifer Wayne recounts scenes from the 1890s when her grandfather was a teacher at the school. Another teacher, named Benbow, was an ex-workhouse boy with bright red hair and who had a withered arm and facial disfigurement received when he had rescued someone from a fire. Benbow was much feared by his pupils but also a source of fascination for Jenifer's father and his friends who were then teenage schoolboys. The boys, who called themselves the Benbow Society, used to secretly eavesdrop on Benbow's classes from outside his classroom window. They took much delight in his nasal yet breathy sing-song voice which had a strong Midland accent, and used with laboured mellifluousness to read poetry. Benbow's fearsomeness was demonstrated on one memorable occasion when, during a lesson on "Christ as the Comforter", he rewarded one inattentive boy with a beating from his withered arm to a repeated tirade of "'E was the Kermforter, the Kermforter, the Kermforter!".

Summer Hill Receiving Home

In 1905, Birmingham established a children's Receiving Home known as Summer Hill at 19 Summer Hill Terrace, Ladywood. Children coming into the union's care went first to Summer Hill for assessment, medical examination etc. Some would then be transferred to the Marston Green cottage homes. Summer Hill also provided accommodation for children who were frequent short-term recipients of the union's care, the so-called ins-and-outs.

Birmingham Summer Hill children's home, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Birmingham Summer Hill children's home, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In more recent times, the Summer Hill building has been occupied by a daycare centre and medical unit.

Monyhull Colony

In 1908, Birmingham, Aston and King's Norton set up a Joint Poor Law Colony at Monyhull near King's Norton to accommodate up to 210 "sane epileptics and feebleminded persons". The site later became Monyhull Hall Hospital but closed in around 2000. The surviving buildings now form part of Lindsworth School.

Monyhull Colony site, 1916.

Monyhull Colony — administrative block, 1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Monyhull Colony — inmates' home, 1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Staff

- 1867 Staff List - Birmingham workhouse

- 1881 Census - Birmingham workhouse

- 1881 Census - Marston Green Homes

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1881 Census - Birmingham workhouse

- 1881 Census - Marston Green Homes

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Birmingham Archives and Heritage Service, Library of Birmingham, Centenary Square, Broad Street, Birmingham B1 2ND. Holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1783-1930); Indoor relief lists (1889-1915); Baptism registers (1864 onwards); Workhouse infirmary (later Dudley Road Hospital) admission and discharge registers (1899 onwards with many gaps and in poor condition); Various other workhouse infirmary records e.g. post mortems, death registers (from early 1900s); Marston Green Cottage Homes registers (1880-1934).

- Birmingham Archdiocesan Archives, Cathedral House, St Chad's Queensway, Birmingham, B4 6EU. Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows in the Workhouse, Western Road — RC Baptisms (1856-1902).

Bibliography

- Dent, Robert K (1893) The Making of Old Birmingham

- Hetherington, RJ (1991) Birmingham Workhouse Records by (in Midland Ancestor, 9).

- Wayne, Jenifer (1973) Brown Bread and Butter in the Basement (London: Gollancz)

- Upton, Chris (2019) he Birmingham Parish Workhouse, 1730-1840.

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.