Oxford, Oxfordshire

Up to 1834

In March 1601, the year of the great Poor Law Act, Oxford's city council resolved that "Robert Phillis, weaver, shall have delivered unto him twenty powndes towards the setting on worcke in spynning of lynnen and in carding and spynning of wollen within the cytty and suburbes; wherein specyall regard must bee had that the idle and loytring sort be sett on worcke, and yf they refuse and doe their worcke amysse, that they be punnyshed by whipping."

In 1724, Richard Hutt was given the lease of Bridewell for seven years at an annual rent of £8 to "receive and employ all such poor as shall be committed by way of His Majesty's justices of the peace by the City". The Bridewell was used at various times both as a general workhouse and also as a house of correction to punish the able-bodied destitute who refused to work. It stood outside Oxford's north gate, at the east side of the street, and was accessed from Cornmarket by an arched doorway. In 1638, the mayor complained that inmates in its barred cellar begged from passers-by and took in tools for breaking the bars.

St Peter le Bailey had a parish workhouse from 1723. From 1726 until around 1735, the parishes of St. Mary the Virgin, All Saints, and St. Martin's parishes joined to lease the Flying Horse (73 High Street) as a workhouse. In 7th August 1727, Oxford Council records note that a lease was renewed to the feoffees of St Mary Magdalen parish for their workhouse.

From the 1720s to the 1760s, the poor were regularly "farmed" by contractors who operated workhouses at Holywell Manor, and in part of the Whitefriars building on Gloucester Green owned by St John's College. From 1726 to 1741 the Gloucester Green workhouse, also known as Gloucester Hall, was used by a contractor named James Piggot, for the poor of at least seven parishes. His 1740 contract with St. Ebbe's required him to provide lodging, fuel, three meals a day, clothing and washing, and basic medical care. The children were to be taught to read and say the catechism, and in addition to daily prayers, all the inmates were to be brought to church once a month to be inspected by the parish. After Piggot retired, St. Martin's switched to using Holywell, and St. Michael's opened its own workhouse. In the early 1750s, a new contractor named Solomon Cross operated the Gloucester Green workhouse with eight parishes under contract with him. The Holywell workhouse was still in use in the late 1760s when the poor of St. Giles's parish were sent there. In 1767, Solomon Cross gave up his activities and again, the parishes were left to try and organise a replacement. The recurring difficulties that arose when contractors came and went resulted in proposals for the formation of a permanent solution in the shape of an incorporation.

Holywell Manor, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1771, eleven of Oxford's parishes were legally incorporated by a local Act of Parliament For better regulating the Poor within the City of Oxford (11 Geo.3. c.14). This was a path followed by a number of other cities around this time, for example Canterbury was incorporated in the same year. The Act gave the Incorporation a number of powers relating to poor relief including the assessment of the poor rate and the erection of a House of Industry.

Oxford's Incorporation was managed by a body called The Guardians of the Poor within the City of Oxford which comprised a number of ex officio members (the city's Mayor, Recorder, Aldermen, Assistants, Town Clerk, and Solicitor) together with elected members from each parish (All Saints, 3; St. Aldate's, 4; St. Ebbe's, 2; Holywell, 3; St. Martin's, 3; St. Mary Magdalen, 4; St. Mary the Virgin, 3; St. Michael's, 3; St. Peter le Bailey, 2; St. Peter in the East, 3; and St. Thomas, 4).

The Guardians of the Poor decided to build a General House of Industry on a five-acre site at Rats and Mice Hill to the north side of the city centre on the site of the palace of Henry the Second. In modern times, Wellington Square and the University administrative offices cover this area. On 14th September 1771, an advertisement appeared in Jackson's Oxford Journal for a builder for the scheme.

1771 Advertisement for builder.

The foundation stone of the building, designed by Mr John Gwynn (also the architect of the Magdalen Bridge and the new market), was laid on May 1st 1772. The ceremony was performed by the Rev Sir J Peshall accompanied by the Mayor of Oxford, the Governor, and the Guardians of several parishes. The building contract specified a cost limit of £4,030 with a completion date of Michaelmas Day, 1773. The location of the new House of industry are shown on the 1792 map below. The southern end of the map also shows the old contractor's workhouse at the north of Gloucester Green.

Oxford in 1792

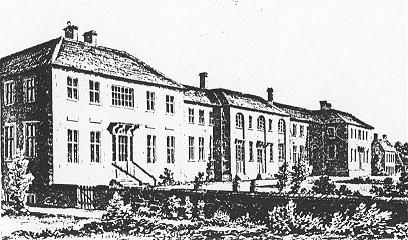

The House of Industry, described as a "very neat stone building", could accommodate 300 inmates. The two-storey main block at the west of the site contained a board-room and chapel at its centre, a carding-room for the men and spinning-room for the women, dining-rooms, and dormitories. Single-storey blocks at each side of the main building contained a bakehouse and brewhouse, and long workshops, each with a supervisor's room. Small separate buildings at the east of site contained a deadhouse, school-house, larder and salting room, and correction room. In the 1790s, wards for the aged and infirm and a nursery were added.

The original Oxford workhouse.

In 1775, the Guardians advertised for a married couple to take over the running of the establishment.

1775 Advertisement for builder.

Eden, in his 1797 survey, records that in July 1795, there were 167 inmates in the Incorporation workhouse:

In St. Clement's, which is not an incorporated parish, the Poor are generally maintained by an allowance at home. Last year (1794) they were sent into the General Workhouse, for which the parish paid 2s. 6d. a head per week.

In October 1826, it was reported that the governor of the Oxford workhouse, a man named Hollis, had decamped with the sum of £1000.

In 1833, a report by Mr H Bishop on the state of the Oxford workhouse was published as part of the evidence being collected by the Royal Commission investigating the operation of the poor laws. Many aspects of the workhouse were criticised and, like Eden, many of the problems were attributed to the high turnover rate of the thirty-four strong board of Guardians. There was a lack of segregation between the sexes, and the lack of regular employment was also a cause for concern. Weaving by this time had been abandoned, and only a little street-cleaning and stone-breaking was given to the inmates. Bishop reported that:

Great improvement in the internal management of the house seems to have taken place under the present master, who appears to have done all in his power, but he is sadly hampered by the interference of one or two meddling and mischievous guardians.

The house is clean, and as regular in its arrangements as its defective construction allows. There is, however, a lamentable want of means of classification, even the sexes cannot be kept separate. The house stands in the middle of a garden, or piece of ground between three and four acres in extent: this lies in one allotment, without the slightest internal fence or division, and surrounded by a high wall. Visitors are admitted by a porter living in a small lodge at the gate. The house opens into this piece of ground; consequently all, men, women, and children, may meet in this space, even after dark. It is hardly necessary to add, that there is, to speak in the most cautious terms, strong suspicion that the bastardy list has been swelled even within the walls.

The diet-table of the house has been constructed on too liberal a scale; the inhabitants of the workhouse are better fed than they could expect to be at their own homes.

The house is not an object of terror, but rather of desire, to the young and able-bodied pauper. There is no seclusion or confinement. Permission, it is true, must be asked to leave the walls, but it is never refused, and the pauper, when once out, need not return till bed-time.

There is, in fact, no government in the house. One guardian frequently undoes what another has done. There is, at the present moment, a guardian, who, probably from a morbid craving for popularity, goes about to the gangs of men that are occasionally set to work (for the house has 16 acres of pasture land to keep cows and horses on, in addition to the garden ground) and will order the men to go to the house and get bread and cheese and beer, in addition to their pay. This took place lately, in the case of eight men engaged in cleaning a ditch, and so far were they from deserving encouragement, that the whole eight did not do the work of two men.

St Giles' Parish

The parish of St Giles, which was not part of the Oxford Incorporation, had leased a house from St. John's College in 1776 for accommodating a number of its poor, although no food, fuel, or furniture was provided. In 1824-5, a new workhouse was erected to the north of the city at Summertown, at a cost of £800 for land and £300 for the building. Mr Bishop's 1833 report was also scathing about both of these establishments:

There is a poor-house situated in the county part of the parish; but this house, though newly built, at some considerable expense, is merely a pauper barrack. There is no master or mistress now, and the occupants are congregated together as in a collection of cottages. It is, as might be expected, a very grievous nuisance to the neighbourhood: women of the town with their bullies have been residing there, and robberies have been effected by its inmates. It is at the present time in rather better order. Still, however, as a place of regulation or discipline, it is worse than useless. The parish, however, contrives to extract this good from it. If there is a pauper likely to be troublesome, and to summon the overseer before a magistrate, the parish authorities remove him to this house if possible, and, by so doing, bring him under the authority of the county magistrates, who are much more pains-taking in their inquiries than some, at least, of the city magistrates.

. . .

It appears, on investigation, that, in seven cases out of ten, the paupers are idle or drunken, abusive or thieving. "I don't care for your work, I can get as much from the parish," is their constant language.

. . .

These various persons are supported in their applications by the city magistrates; and the parish authorities and vestry, knowing how useless it is to look to them for countenance, prefer paying these people their annuities to contesting them and failing.

A considerable quantity of casual relief takes place in clothing. Shoes are made by parishioners, who charge 14s. a pair, for articles which would be sold to private individuals for 12s.

No balance sheet is published, neither are the paupers' names printed. No visitation of them at their houses takes place. They have been all ordered to attend a vestry for examination, and the absentees were struck off, but were, however, restored to the pay-list the next week. There is no parish work of any kind. The paupers, at one time, were set to stone-breaking; but it was found that they destroyed their tools, and that their earnings were insufficient to pay for the repairs.

The assistant-overseer is generally a decayed tradesman, with a salary of 50l. per annum. He was to have lived in the poor-house, and taken the superintendence of the paupers; but the present one, finding the place, or the inhabitants, disagreeable, left the house and came to Oxford, and no notice has been taken.

The annual amount of money actually expended on the poor is 1317l. The overseer comes into office every year, and this is a great evil, as the new officer is always assailed with a number of false complaints.

The "pauper barrack" was located on what is now Mayfield Road in Summertown. After its closure in 1836 it was sold for only £300.

St Giles' former Summertown workhouse, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1834

Oxford's Local Act status made it largely exempt from the provisions of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act although the Poor Law Commissioners tried to persuade the Incorporation to convert to a Poor Law Union, which it declined to do. The PLC also proposed the Incorporation should add Oxford's three other parishes (St John the Baptist, St Giles, and St Clements) to its membership. St John the Baptist, at the centre of the city, was included, while St Giles and St Clement were rejected. The apparent reason was that the Incorporation had a contract with the City for its paupers to clean all of Oxford's streets, including those of its non-member parishes, for which it received a net annual income of £600. This revenue would be lost if the Incorporation took on St Giles and St Clements. These parishes therefore formed the basis of a new Poor Law Union based at Headington. Oxford continued as an Incorporation until 1926. Some slight changes took place in its composition, most notably the addition of Grandpont from 1889.

According to the VCH, conditions in the workhouse did not improve after 1834. In 1843, arrangements for the sick and the children were under criticism, as was a failure to comply with a decision in 1833 that women and young girls should be separated — though prostitutes were now being separately housed. By 1848, overcrowding had reached a point where inmates were sleeping three to a bed and the board-room was in use as a dormitory.

Plans for a new workhouse were discussed in 1837, 1840 and 1847. In 1850, a site was bought for a new building at what later became Park Town. However, this was resold for a housing development to finance the setting up of the industrial school at Cowley Fields (see below).

In 1859, the Guardians became embroiled in a legal dispute with a Mr Green over an unpaid bill of £1450 for surveying and valuing work he had undertaken. Green successfully took the Board to court but the Guardians continued to prevaricate over settlement. As a result, Green — with the support of the High Sheriff of Oxfordshire and his officers, announced that the contents of the workhouse and industrial school would be auctioned off on December 5th.

Oxford Workhouse Contents Sale, 1859.

Although it is not clear if the auction actually took place, the catalogue of 161 lots produced for the workhouse sale provides an interesting inventory of the workhouse furnishings as the following extracts show:

| Old Lady's Bedroom |

|

| Old Lady's Sitting Room |

|

| Dining Hall |

|

| Board Room and Entrance |

|

| Chapel |

|

| Mangle Room |

|

| Oakum Room |

|

| Apothecary's Shop |

|

| Brewhouse |

|

| Laundry |

|

| Drying Room |

|

| Stores |

|

| Larder |

|

| Kitchen |

|

| Kitchen, No. 2 |

|

| The Master's Bedroom |

|

A number of potential sites were considered for the new workhouse, including one at Holywell, several in the vicinity of Iffley Road, one at Summertown, one on the Abingdon Road, and land adjacent to the Industrial School at Cowley Fields. Eventually, in 1861, a site of around 12 acres on the north side of the Cowley Road was purchased from Pembroke and Magdalene colleges for about £2,800. A competition, open only to Oxford architects, was held to design a new workhouse building. The winner was Mr William Fisher of St Clements.

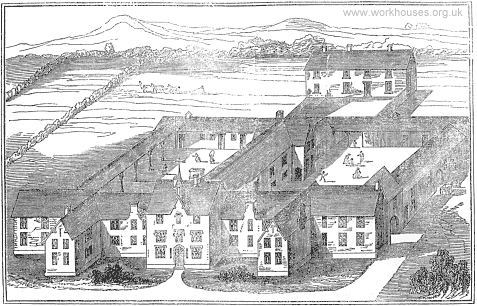

Bird's-eye view of Cowley Road workhouse, 1861.

Above is a bird's eye view of the proposed new building. It comprised four main parts: an entrance range (containing porter's lodge, boardroom, casual wards etc.), a main range housing the master in the centre and inmates in the wings, with kitchen and dining-hall to the rear; a chapel, and an infirmary. A ground plan is shown below (click on the plan for an enlarged view).

Ground floor plan of Cowley Road workhouse, 1861.

As can be seen on the 1875 map below, the workhouse chapel was relocated to the eastern edge of the site, possibly to allow it a more conventional east-west orientation.

Oxford workhouse site, 1875.

The building's foundation-stone was laid on 6th April, 1863, and it was completed in 1865 by local builder Mr Curtis. The new building, designed to accommodate 330 inmates, was constructed in red and white brick, with dressings of Bath stone. In addition to the cost of the land, and building costs of £6,000, other expenses too the total bill to around £9,000. However, most of the costs were met by the sale of the 5½-acre site of the old workhouse which raised over £8,000.

Two of the rooms (off the work-yard on the plan above) indicate some of the main work activities performed by the inmates:

- the oakum room, where old ropes were picked by hand into loose fibres (then used to caulk the gaps between the planks on boats)

- the gypsum room, where gypsum (used in plaster-making) was crushed and bagged

Oxford workhouse wnfirmary block, from the west.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1882, new casual wards were added and were used by some four to five thousand tramps a year by the 1890s, growing to a figure of 12,450 in 1908.

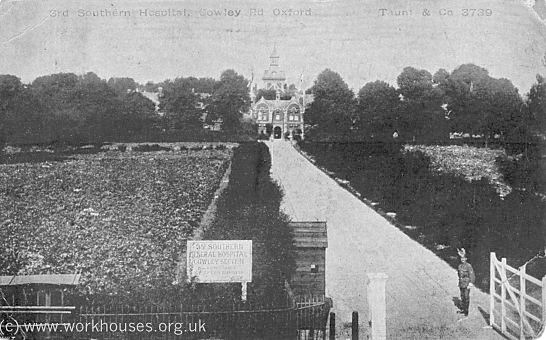

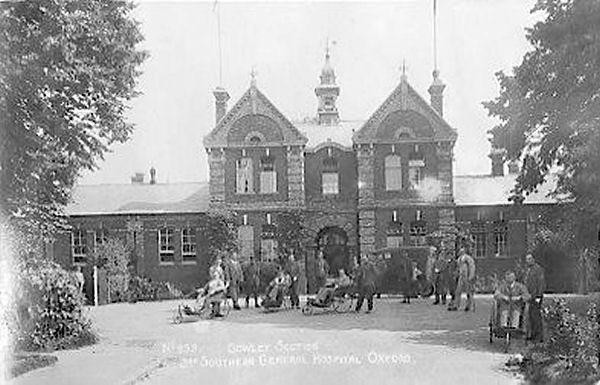

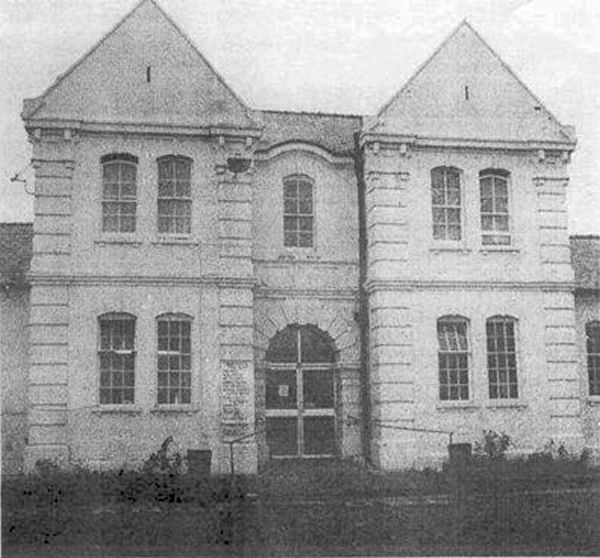

During the First World War, the inmates were transferred to other institutions in the area and the workhouse was taken over as the Cowley section of Oxford's Third Southern General Hospital dealing with the treatment and rehabilitation of war casualties. The pictures below are from this period.

3rd Southern Hospital entrance, c.1917.

© Peter Higginbotham.

3rd Southern Hospital, c.1917.

© Oxfordshire Photographic Archive.

3rd Southern Hospital, c.1918.

© Peter Higginbotham.

3rd Southern Hospital, c.1917.

© Oxfordshire Photographic Archive.

In 1931, former Oxford MP Frank Gray recorded his undercover experiences in the casual wards of Oxfordshire workhouses which he visited disguised as a tramp. Of Oxford he wrote:

It must want many minutes to six o'clock when a permanent inmate passes and says: "Why don't you go in? It's been open for a long while." We enter a brightly lighted room with spotlessly clean tables and forms, and to these are brought bread, margarine, and cocoa, before any inquisition, search, or inquiry is held; for this is an institution which has not lost its soul.

"Dad" is of the gathering. He sits next to me. He pours a little sugar into my mug of cocoa — the widow's mite — a much greater act from a tramp to a tramp than it may appear.

. . .

The meal at the Oxford casual ward is over. The porter calls first for those who have come from Woodstock. A lot get up — so do I — and the porter says: "You are as deaf as I am." In a later class I get up again. I am searched. How well I know the porter and how well he knows me! But he does not recognize me. I am passed on to a permanent inmate, who is lending a hand — and he superintends me while I strip with others, pile my bundle of rags on theirs, and take my bath. There is certainly more ceremonial about the bath at Oxford, and no man is entitled to complain if he uses the water after another — some use it without complaining. You see this consideration becomes a mere unnoticeable detail in the general horror of life as a tramp.

I get a workhouse shirt, go into a spacious, healthy, and clean department, and, best of all, to a spring bedstead, straw mattress, and straw pillow. There is sufficient space, too, between the bedsteads. We are treated like decent men. Some of us are, and all have got a great deal of good in them. If men's hearts could be searched it would be found that this better treatment has more than once stirred that latent better spirit to rise from the level of the tramp and the outcast.

And so to sleep.

On the morrow my task before release is to scrub the floors of two large outhouse dormitories, apparently overflow casual wards.

. . .

We are now about to parade for our departure. I see "Dad" at the parade. I watch a young official go up to him and hear him say: "Why don't you stop here with us, Dad? You are too old for this game now. You will be getting knocked down on the road." At this act of kindness a tear comes to the old man's eye — he is still capable of responding — and then he passes out, passes out to pick up the trail of death.

As I walked from the Oxford workhouse, released, I reflected that there were two "spikes" within two miles of each other conducted on very different lines. It might fairly be supposed that if my description of the two be correct, Headington would be deserted by tramps and Oxford overcrowded. This is not so, and there are good reasons why — reasons taking you to the heart of the problem of vagrancy.

Seven out of ten tramps stayed at both Headington and Oxford on the same journey. A tramp said to me: "I hate to be — — and — — about," and when he has said this he has expressed the terms in which many tramps think. They like to be left to their own devices, and to gain this they will put up with a lot of filth and beastliness.

We tramps are all the same just under the skin. We prefer a dungheap and a cigarette to a clean prison cell and fifty questions. Do not think, late Guardians, that by locking dirty men with hunks of bread in a dirty, insanitary hole without interference, question, or inquiry, you could have emptied your casual wards.

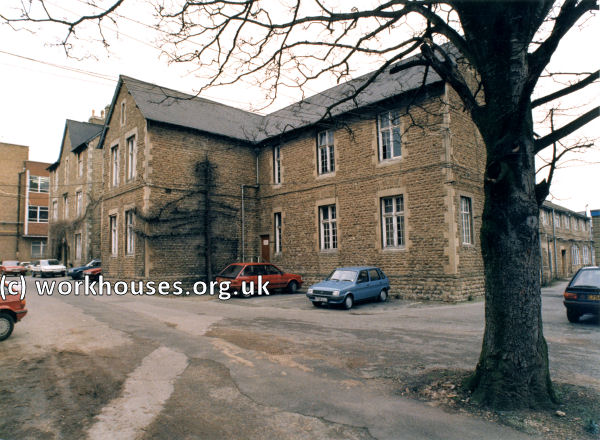

Following the 1929 Local Government Act, the workhouse became a Public Assistance Institution with the City Council taking over its management. It then served as an EMS (Emergency Medical Services) hospital during the Second World War. With the advent of the National Health Service in 1948, Cowley Road Hospital was taken over by the Ministry of Health, predominantly caring for geriatric patients.

The hospital was closed in 1981. The main buildings were gradually demolished until only the central part of the entrance range remained, forlornly awaiting its turn.

Entrance range awaiting demolition.

Courtesy of Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd.

The only surviving remnant of the workhouse buildings is the chapel which has now been converted into an Asian community centre.

Workhouse chapel from west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cowley Industrial Schools

In 1853-4, the Oxford Incorporation "fully alive to all the evils which result from the association of the children and the adult paupers" erected industrial schools on a ten-acre site at Cowley Fields, three miles out of Oxford. The establishment was located was opposite what was to become the eastern end of Fern Hill Road, where the forecourt of the BMW car works now lies.

Cowley School site, 1875.

The building was designed by Edward G Bruton and it was originally envisaged that it would become the central industrial (or "district") school for 220 pauper children from the whole of Oxfordshire.

Cowley Fields Industrial School from the south, 1855.

Cowley Fields Industrial School plan, 1855.

The building had a double-courtyard layout with boys accommodated to one side and girls the other, with the dining-hall placed in between. School rooms and classrooms were located at the front of the building while to the rear were a washhouse, laundry and bakehouse on the girls' side, and various workshops and a farmyard on the boys' side. A separate infirmary lay behind the main school buildings.

Cowley Fields Industrial School from the south

Courtesy of Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd.

Cowley Fields Industrial School from the south-east, c.1988.

In 1858, a report by Poor Law Board Inspector, Mr Pigott, noted:

In 1894, a water tower was erected with two tanks able to hold 8,000 gallons pumped from wells on the site and distributed by gravitation. In 1901, a chapel was added at a cost of £1,200.

Up until 1920, the children were educated on the premises but were then allowed to attend outside schools in the city. At around the same time, the site became known as The Poplars Schools. After being taken over by Oxford City Council in 1930, it continued in operation until around 1937. The building was demolished in 1988.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Oxfordshire History Centre, St Luke's Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2EX. Holdings include: Births (1900-1930); Baptisms (1843-93); Deaths (1841-1930); Lunatics (1869-1930); Indoor and outdoor poor (1872-1915); Guardians and staff lists; Printed accounts (1812-1930 with gaps); etc.

Bibliography

- Victoria County History of Oxford - Volume 4: The City of Oxford, 1979, OUP.

- Byung Khun Song (1999) Continuity and Change in English Rural Society: The Formation of Poor Law Unions in Oxfordshire in The English Historical Review, 114, No. 456. 314-338.

- Gray, F. (1931) The Tramp: His Meaning and Being JM Dent.

- Hobson, M.G. (1954) Oxford Council Acts, 1701-1752 Oxford Historical Society.

Links

- Oxfordshire History Centre, St Luke's Church, Temple Road, Cowley, Oxford OX4 2EX.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.