Bristol, Gloucestershire

Up to 1834

In 1696, Bristol's eighteen city parishes, plus the Castle Precincts district, were incorporated under a parliamentary Local Act. The Act created the Bristol Corporation of the Poor, which operated a joint poor relief system across the whole city, including the setting-up of workhouses and the appointment of paid officers. Over the next century, around thirty other cities followed Bristol's example, including Exeter in 1697, and Colchester, Crediton, Hereford, Kingston-upon-Hull, London, Shaftesbury, and Tiverton, all in 1698.

The main instigator of the Bristol scheme was John Cary, who in 1700 published an account of the Corporation's early years. The Corporation was managed by a Board of Guardians — four from each of the city's twelve "wards" — plus the Mayor and Aldermen, making a total of sixty.

After various delays, in 1698 a building was rented for use as a workhouse. The New Workhouse, as it became known, was to house a hundred pauper girls. Staff were appointed including a Master "To receive in Work, and deliver it out again, and to keep Accounts of the House &c.", a Mistress "to look after the Kitchin and Lodgings, to provide their Meals at set Times", four Tutresses "to teach them to Spin, under each of which we designed to put Five and twenty girls", and a School-Mistress "to teach them to read". Servants were initially employed in the kitchen to perform cooking and washing but these were soon dispensed with and the work done by the older girls. An old man was appointed as door-keeper and general porter.

On arrival, the new inmates were stripped and washed by the Matron and given a set of new clothes. The diet provided for the girls included "Beef, Pease, Potatoes, Broath, Pease-porridge, Milk-porridge, Bread and Cheese, good Bear [Beer], Cabage, Turnips etc." The cost of maintaining each inmate was 16d (approximately 7 pence) a week. Prayers were said twice daily with a church service on Sunday. In good weather the girls were allowed to walk on the hills with their Tutresses. Illness amongst the inmates was common with around twenty ill at any one time, suffering from measles, smallpox and "other distempers". In 1697, Thomas Dover, a local doctor and the inventor of "Dover's Powder" (a preparation containing ipecacuanha and opium), offered his services, free of charge, as physician to the New Workhouse.

The girls worked at their spinning for ten and a half hours a day in summer, a little less in winter. After their initial training, they were hired out to local manufacturers. However, the coarseness of the yarn they produced soon resulted in complaints and low payment rates of 8d per pound. As a result, the Corporation offered spinning work to all the city's poor, many of whom could produce very fine yarn which fetched up to 3s.6d. per pound.

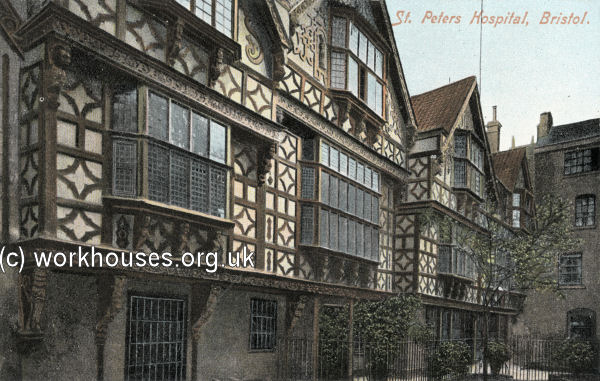

In 1698, the Corporation purchased a house at the south of St Peter's church once owned and largely reconstructed by sugar merchant Robert Aldworth. The building had recently been occupied by the Treasury as a mint and so it became known as the Mint Workhouse and was used to house the elderly, boys, and young children. In August of that year, a hundred boys were moved in. They were occupied in "spinning Cotten Wool, and weaving Fustians" for which they were able to generate the creditable income of £6 per week. The boys were also taught to read and (unlike the girls) to write. Next, elderly inmates were admitted. They were clothed and given "such Employments as were fit for their Ages and Strengths. Finally, young children were taken in and put in the care of nurses. In 1709, the girls from the New Workhouse were moved to St Peter's.

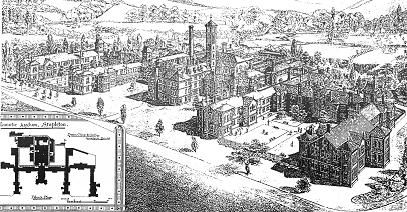

Bristol St Peter's site, 1884.

Despite Cary's rosy picture of the workhouse scheme, it was not without its critics. In 1711, an anonymous pamphlet claimed that the workhouse was "crowded with idle, Lazy and Lewd People". The economics of the scheme were also questioned with the cost of running the workhouse amounting to almost half of the annual poor rate (then £2,376 16s. 5d) for the benefit of 170 inmates. The Mint Workhouse later became known as St Peter's Hospital and from 1901 served as the Board of Guardians' offices. The building and survived until 1940 when it was destroyed by wartime bombing.

Bristol St Peter's Hospital.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A room in the Mint workhouse known as the Court Room was used as the guardians' board-room.

Bristol St Peter's Hospital, board-room.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, reported:

Few cities possess such a number of public charities as Bristol. There are 30 alms-houses, in which 83 men and 230 women reside, with an allowance nearly sufficient for their support. There are several charity schools in which about 960 children are educated, and most of them clothed and maintained. The donations to the Poor are considerable, but the exact amount could not be ascertained.

In a submission to the Royal Commission, whose Report would form the basis of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, St Peter's workhouse was described (Large, 1995) as:

Able bodied-men were employed from 6am to 6pm breaking stones at the Clifton Hot Well, for which they received 3s. 4d. a week, which was about half the minimum agricultural wage in the area.

In 1832, when a major cholera outbreak was causing severe problems at St Peter's, the Corporation began renting, and subsequently purchased, the old prison on Manor Road, Stapleton. This had been built by the Admiralty in about 1779 to hold prisoners from the wars with the American colonies, and with France from 1793.

Braine in his 1891 description of "Fishponds" noted that:

Bristol Old French Prison from the south-west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1834

In 1835, Bristol's new city council extended the city's boundaries to encompass the parishes of St Philip and Jacob Without and Clifton, the united district of St James and St Paul, and parts of the parishes of Bedminster and Westbury-on-Trym. These changes, together with the long-standing existence of Bristol Incorporation (whose status exempted it from the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act), caused some complications in the setting-up of poor-law unions in and around Bristol. Two new unions were created: Clifton (renamed Barton Regis in 1877) included the Gloucestershire parishes in the area to the north and east of the city, and Bedminster (renamed Long Ashton in 1899) covered the Somerset ones to the south and west. The Bristol Incorporation then comprised the city parishes of All Saints, Castle Precincts, Christ Church, St Augustine the less, St Ewin, St James, St John, St Leonard, St Mary-le-Port, St Mary Redcliffe, St Michael, St Nicholas, St Paul, St Peter, St Philip & St Jacob, St Stephen, St Thomas, St Werburg, and Temple.

Between 1835 and 1897, the Bristol Corporation of the Poor continued to operate the St Peter's and Stapleton workhouses.

In October 1867, the Stapleton workhouse was the subject of an inspection report by the British Medical Journal, which rated it as good. In the Imbecile Department, in a wing of the main building, the male part consisted of a dining-room, two day-rooms, and five sleeping-wards, containing over fifty people, who were attended to by three paid nurses, assisted by the most competent of the patients. The day-rooms were light and cheerful, and were furnished, amongst other things, with a bagatelle-table. The beds occupied by patients subject to epilepsy had well padded sides to them, and those used by patients who were in the habit of passing their urine under them, were covered with macintosh, and each had an opening in the centre for the water to run through into a vessel placed below. There were excellent bathrooms and lavatories attached to these wards, with a plentiful supply of hot and cold water. The workhouses laundry facilities were noted as being particularly good. Further details are available in the full report.

New male and female infirmary pavilions were opened in 1868. Each pavilion contained three wards, two on the ground-floor, 40 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 13 feet high; and one on the upper floor, 80 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 14 feet high. Each pavilion contained thirty-two beds, each with 1800 cubic feet of space. The two pavilions were connected to each other at one end by a passage, which also connected to the infirmary's own kitchen.

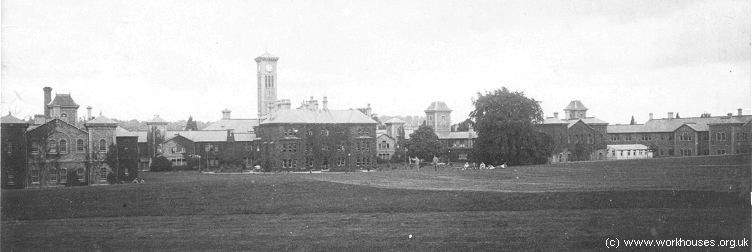

There was a major redevelopment of the main building in about 1890, together with the erection of a low single-storey entrance block along Manor Road, and a chapel.

Bristol Stapleton site, 1901.

Bristol Stapleton Workhouse from the south, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bristol Stapleton Workhouse from the south, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bristol Stapleton workhouse, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bristol workhouse north-west block from the south-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bristol workhouse chapel, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1897, following the extension of its boundaries to cover the whole of urban Bristol, the Corporation was reconstituted as a single Poor Law Parish. It absorbed many of the parishes previously included in the Barton Regis (formerly Clifton) Union. It also took over the Barton Regis workhouse at 100 Fishponds Road in Eastville, with the much reduced Barton Regis Union building a new workhouse at Southmead. This arrangement lasted only to 1904, when the Barton Regis Union was wound up and its parishes dispersed between a further enlarged Bristol City and the Chipping Sodbury Union. The new Southmead workhouse became the second in six years to be inherited by Bristol from Barton Regis.

The enlarged Bristol Board of Guardians continued to hold their meetings at the St Peter's Hospital site. The picture below shows the members outside the building, possibly in 1930, when the Board was abolished and their responisbilities were taken over by the city council.

Bristol Board of Guardians, St Peter's Hospital, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A few of the guardians in the above picture are identified as follows:

- Front row (left to right) — 2: Miss Meade-King; 3: Mrs Webb; 5: Councillor Burt; 6: Councillor Mrs Pheysey; 11. Harry Fanson; 12: Mr T.C. Lewis.

- Second row — 2: Mrs Hennessey; 6: Mrs Hampton;.

- Third row — 3: David Jenkins; 4: Gildbert Adams; 9: David Lewtas.

- Fourth Row — 5: Dick Daniel.

In 1930, the Stapleton workhouse became Stapleton Institution and by the Second World War, the site was mainly used for the care of mental cases, and the aged and infirm. It later became Manor Park Hospital, and is now called Blackberry Hill Hospital. The St Peter's building was destroyed by wartime bombing in 1940.

Downend Cottage Homes

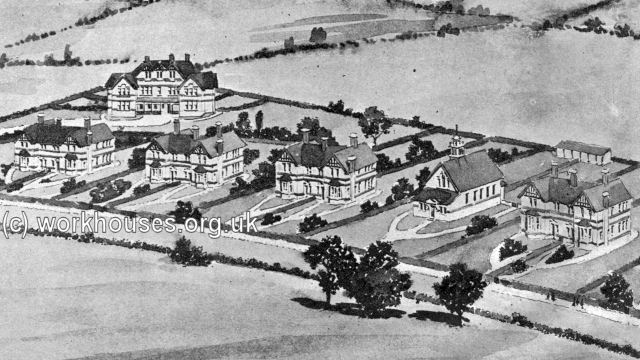

In 1902-5, the Bristol Guardians erected a children's cottage homes development at Downend, about a third of a mile to the north-east of the Stapleton workhouse. This site was healthily situated among rural and wooded surroundings at an altitude of nearly 300 feet.

Bristol Downend cottage homes site, 1919.

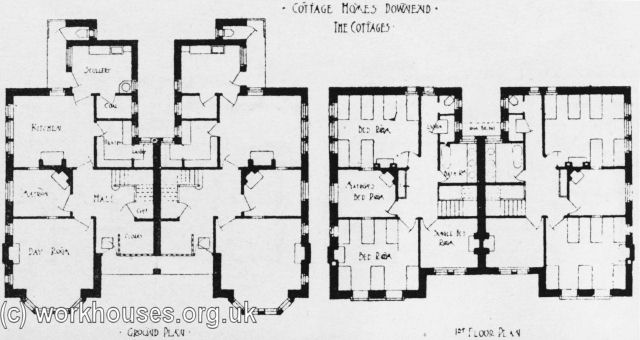

The scheme, designed by Messrs. La Trobe and Weston of Bristol, included seven semi-detached pairs of homes arranged along one side of a gently curving crescent. A school/communal building was placed between the third and fourth pairs of homes, and a 36-bed convalescent home lay at the far end of the site. Each home accommodated up to 12 children looked after by a house-mother.

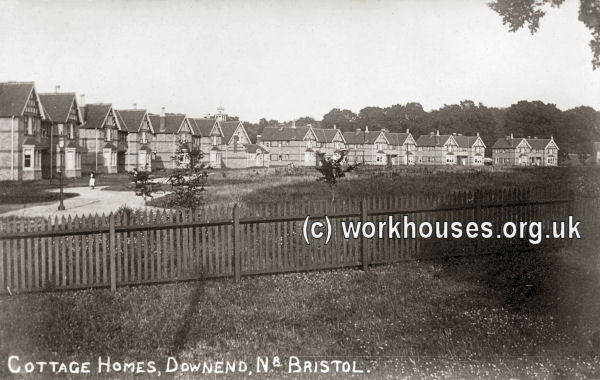

Downend Cottage Homes from the west, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes from the south, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes cottage layout, 1904.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes from the south, 1904.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes school/hall, 1904.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Downend Cottage Homes convalescent home, 1904.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1930, the homes continued in operation under the control of Bristol City Council. In 1962, the site became The Crescent Approved School for Girls. All the buildings were demolished in 1983 and modern housing now occupies the site.

Other Children's Homes

By 1914, Bristol had also established a pauper children's home on Snowdon Road, a little to the south of the Stapleton workhouse. In 1924, eight scattered homes were in operation at 114-5 Beaufort Road, St George's; 1-2 Park Road, Staple Hill; and 255/256/260/262 Beechwood Road, Charlton Road. There were also a Headquarters and Receiving Homes at Channon's Hill (i.e. the Snowdon Road site, see map above) and Service Boys' Homes on Pritchard Street.

Channon's Hill Homes - administrative building, 2011.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Channon's Hill Homes - children's house, 2011.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Channon's Hill Homes - children's house with original outbuildings at rear, 2011.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bristol Lunatic Asylum

In 1861, the Bristol Lunatic Asylum was opened on a site immediately to the north-west of the workhouse as shown on the 1901 map below.

Bristol Asylum site, 1901.

Most workhouses provided accommodation specifically for the mentally ill, particularly less severe cases for whom workhouse accommodation was much cheaper than the costing of using a county asylum. There was, however, increasing concern around this time about the care of "pauper lunatics" in workhouses. For example, in 1856 in the adjacent Union of Clifton, a women called Eliza Canningford had been placed in the workhouse's Female Imbecile Ward. She had acquired a knife and cut her throat in the water-closet. No inquest had been demanded. An inquiry discovered that neither of the workhouse's pauper wardens had been on duty at the time. Also, it was the workhouse's practice to keep together both imbeciles and dangerous lunatics in the same ward. As a result of such incidents, there was an increasing move towards the setting up of publicly-administered county lunatic asylums which could provide more specialized care for the mentally ill.

The Bristol Asylum was an impressive building and was the subject of a feature in the architectural journal Building News in April, 1891.

Bristol Asylum, 1891.

During the First World War, the asylum became Fishponds Military Hospital.

Bristol Asylum, c.1916.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Former Bristol Asylum, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The former Bristol Lunatic Asylum buildings are now used by the University of the West of England.

Staff

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861) — St Peter's Hospital

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861) — Stapleton workhouse

- 1881 Census — Stapleton workhouse

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Bristol Record Office, 'B' Bond Warehouse (in the 'Create Centre' section from 3-Dec-2013), Smeaton Road, Bristol BS1 6XN. Bristol workhouse records were virtually all destroyed by enemy action in 1940.

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1711) Some Considerations offer'd to the Citizens of Bristol, relating to the Corporation for the Poor in the said City. (Bristol)

- Ball, Roger; Parkin, Di; Mills, Steve (2016) 100 Fishponds Road: Life and Death in a Victorian Workhouse (Bristol Radical Pamphleteer Leaflet #34)

- Braine, A (1891) The History of Kingswood Forest

- Cary, John (1700) An Account of the Proceedings of the Corporation of Bristol in Execution of the Act of parliament for the better Employing and Maintaining the Poor of that City London: F Collins.

- Large, David (1995) Bristol and the New Poor Law (Bristol Branch of the Historical Association)

- Summers, Marian & Bowman, Sue (1995) Of Poor Law, Patients and Professionals... A History of Bristol's Southmead Hospital

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.