Poplar, Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

In 1735, the Poplar parish overseers set up a workhouse in three houses leased for the purpose at the north side of Poplar High Street. In 1757, the workhouse relocated to the south side of the High Street. With the opening of nearby docks in the early 1800s, the population in the area grew and the additional land was acquired to expand the site. Two new buildings were erected in 1815-17 with James Walker as architect and the firm of Horne & Gates as the building contractors.

The three main buildings at this time were: the entrance block at the north, facing onto the High Street, which contained the Master's quarters, a town hall for the Trustees use, and some inmates accommodation; an eastern wing containing inmates' wards; and a workshop block to the west. The Trustees wanted to add a further accommodation block on the site of the National School at the west but were unable to buy the property.

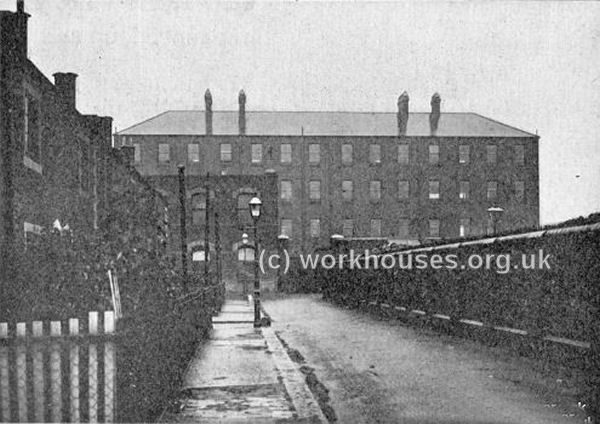

Poplar entrance block from the north

In 1816, it was noted that Stratford-le-Bow's parish workhouse was housed in a "mansion of some antiquity... the ceiling and chimney-case of a large room in the first story are plentifully ornamented with stucco and carving, but neither possesses any armorial allusions."

Stratford-le-Bow site, c.1830.

After 1834

On 20th December, 1836 the new Poplar Poor Law Union was formed. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 15 in number, representing representing its 3 constituent parishes as follows (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one): Poplar, including Blackwall (8); Bromley (4); Stratford-le-Bow (3). The population falling within the new Union at the 1831 census had been 25,066 — ranging from Stratford-le-Bow (population 3,371) to Poplar (16,849). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £15,869.

The new union took over the existing Poplar parish workhouse. In the 1840s and early 1850s, a number of additions were made including separate children's accommodation, a male infirm ward, and a casual ward with an adjoining stone-breaking yard. The site layout at this time is shown on the 1867 map below.

Poplar workhouse site, 1865.

The union had an infirmary on Upper North Street, originally used as an isolation hospital during the cholera epidemic of 1831-2 and enlarged during another outbreak in 1849

In the 1850s, the Poor Law Board's Inspector criticised the accommodation and described the workhouse as 'irregular and without design as a whole'. The Guardians considered two improvement schemes, on to add new wings to the existing buildings, the other to rebuild the whole workhouse. The latter was decided upon and in 1869-72, the firm of Hill, Keddel and Waldram constructed a new building to designs by John Morris & Son, retaining only the 1817 High Street block.

The layout was based around an east west corridor spine with a the major buildings running off it. The new buildings, mostly of four-storeys, also included wards for lunatics and probationers. There was also a Gothic-style chapel at the south of the site.

Poplar workhouse probationers wards', architects drawing 1869

© Peter Higginbotham.

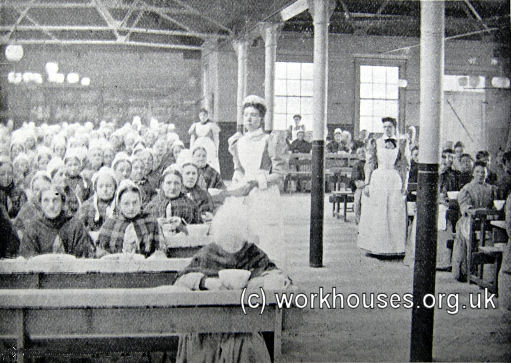

Poplar workhouse dining hall, c.1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar workhouse female sick ward, c.1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1871, the Local Government Board supported an experiment whereby Poplar workhouse admitted only able-bodied paupers who would be subjected to a 'labour test' — performing hard manual labour in return for a subsistence allowance for their families — together with strict discipline and the most basic of diets. Any spare capacity was offered to other metropolitan unions and parishes. The scheme proved to be effective with an "Order for Poplar" proving a strong deterrent to able-bodied applicants. However, such Orders increasingly came to be used by unions wishing to get rid of undesirable or troublesome applicants. This could include the aged and physically defective as well as the able-bodied. As early as 1873, the workhouse Medical Officer was complaining of the numbers of inmates who were not able-bodied. In 1880, 235 of the 1284 men admitted to the workhouse were aged over sixty.

During this period, Poplar had an arrangement with the adjacent Stepney union to accommodate its other classes of inmate, with the aged and infirm going to Stepney's workhouse at Bromley, and the sick to the newly opened Poplar and Stepney Sick Asylum.

The 'Poplar Experiment' continued until 1882 when the demand for accommodation for increasing numbers of Poplar's own sick and infirm led to the workhouse reverting to the union's sole use. In its place, the Local Government Board persuaded the Kensington union to turn over one of its establishments for used as an able-bodied test workhouse. Similar schemes were also implemented in a number of other large cities including Birmingham, Manchester and Sheffield.

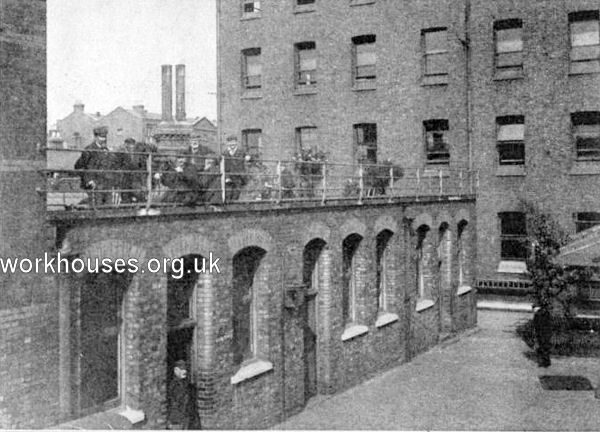

By 1889, the workhouse was again admitting the aged and infirm and rising numbers necessitated the building of two additional accommodation blocks and an extension to the dining hall. Further additions were made in 1893 and again in 1901, resulting in the site being described in 1903 as 'a veritable small town'.

Poplar workhouse site, 1895.

Poplar workhouse men's ward block from the west, c.1902

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1892, two new working-class guardians were elected to the Poplar Board: Will Crooks and George Lansbury. Will Crooks, who came from an impoverished family, had himself spent some time in the Poplar workhouse as a child. On one visit to the Poplar workhouse, Crooks was barred by the Master without whose permission a Guardian could be refused admittance. Crooks and Lansbury raised such a protest about this regulation that it was changed so that a Guardian would have the right to enter a workhouse at any reasonable hour. This small change resulted in am improvement in workhouse conditions across the country.

Poplar workhouse women's day-room, c.1908.

Within a few years, Crooks had become Chairman and the Board began to operate an open-handed policy of outdoor relief, with little regard to the resulting cost for the local rate-payers. 'Poplarism', as this policy, came to be called, promoted the view that the rich parts of London should subsidise the costs of the workhouse and outdoor relief in the poor parts such as the East End where Poplar was located. The Poplar Board introduced a number of reforms into the workhouse such as abolishing the workhouse uniform, improving the food, and allowing tea and tobacco to the aged. Poplar's generous out-relief policies brought Crooks before a Local Government Board inquiry in 1906 but, despite a number of criticisms being made of various aspects of the union's administration, he was largely exonerated.

Poplar workhouse — labelled as a 'Pauper's Paradise' in 1906.

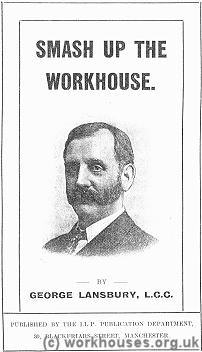

George Lansbury went on to become a member of the 1905 Royal Commission on the Poor Law and the Unemployed and a signatory to its minority report which recommended the dismantling of the workhouse system. This was a cause he further promoted in a 1911 pamphlet provocatively entitled Smash Up The Workhouse.

George Lansbury's 1911 Pamphlet

The Union was renamed Parish of Poplar Borough in 1907. After 1913 the workhouse became know as Poplar Institution, passing into the control of the London Council in 1930. The site suffered considerable damage during the Blitz in 1940. The buildings were eventually demolished in 1960, although the site lay derelict for many years after,

The Poplar and Stepney Sick Asylum, Devon's Row

In 1868, the recently formed Metropolitan Asylums Board set up six new Sick Asylum Districts for the purposes of providing hospital care for the poor on separate sites from workhouses. One of the new Districts was the Poplar and Stepney Sick Asylum District and comprised the area covered by the two poor law unions. Soon afterwards, the new District erected a large hospital at Devon's Row in Bow to which sick paupers from Poplar and Stepney were from then on admitted.

The Forest Gate School

In 1897, following the dissolving of the Forest Gate School District, Poplar took over the Forest Gate school building on Forest Lane. It was used as a training school until 1906 and then, from 1908, it was used as a branch workhouse for able-bodied paupers. In 1911, the West Ham Union acquired the premises for £41,000 for use as an overflow workhouse.

The Poplar Labour Colony

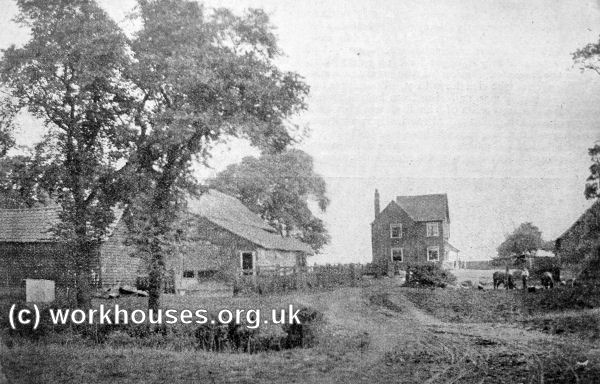

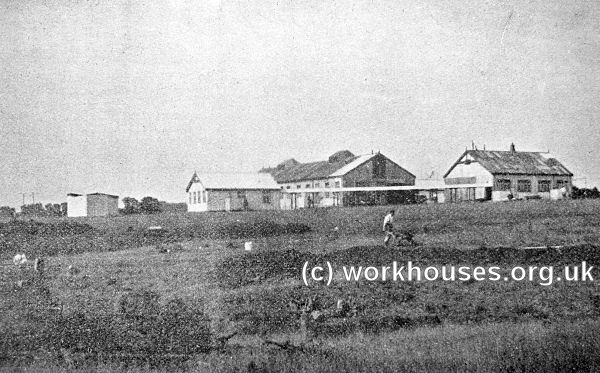

In 1904, as part of its 'Poplarism' policies, the union set up a 'labour colony' — effectively a branch workhouse for able-bodied men — on the 200-acre Sumpner's Farm it had purchased at Dunton near Laindon in Essex. Through a scheme known as the modified workhouse test, unemployed men were admitted as workhouse inmates with their wives and families also being given out-relief. The colony, for up to 100 inmates, was intended to introduce more productive activities into the labour test — farm work instead of stone breaking and oakum picking — and to encourage self-sufficiency amongst the able-bodied poor. The scheme was financed by Joseph Fels, a wealthy American philanthropist.

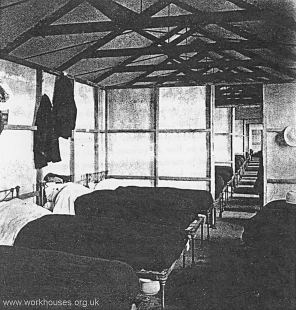

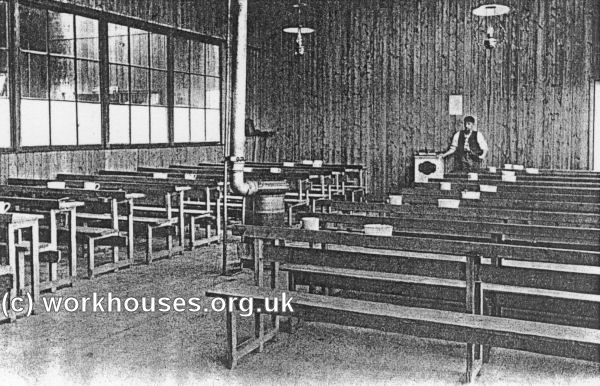

Unlike the new training schools being erected at Hutton (see below), little was spent on adapting the existing farm buildings. A dormitory and dining-hall were provided from two second-hand iron buildings, and a new laundry, lavatory block, and superintendent's house were of cheap construction.

Poplar Labour Colony site, 1922.

Poplar Labour Colony buildings, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony buildings, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony dormitory, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony dining-hall, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony dining-hall, 1904.

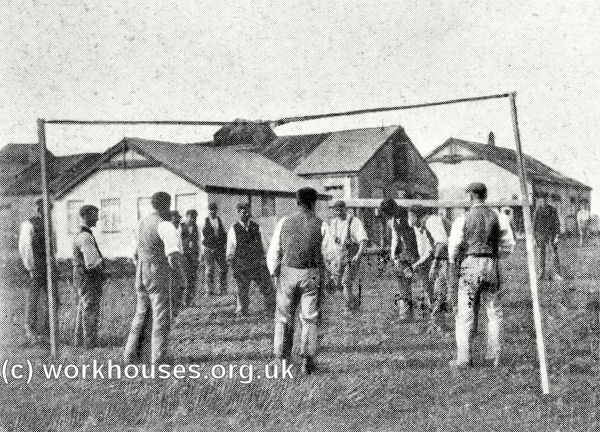

Poplar Labour Colony, inmates playing football, 1904.

In its early days, the scheme was hailed as a great innovation. A glowing report of the scheme appeared in the London Illustrated News:

At their own request about four months ago, one hundred men were taken from the Poplar Workhouse and transferred to a labour farm colony at Laindon, in Essex, where they were employed on the land. Owing to the peculiar state of the law, during the whole of this period not one penny has been received by way of wages. And remarkable as it may seem, although these labourers, who are deemed unworthy of hire, were at liberty to throw down their tools at any moment, they have almost without exception chosen to continue the hard life of husbandry in preference to the lounging lot that would have befallen them as "able-bodied inmates." Surely here, then, is the willingness of the unemployed, of which the puling pessimists would do well to take full note? As to the genesis of the colony: on March 5, 1904, Mr. Joseph Fels, an American gentleman living in London, handed over to the Poplar Guardians a farm of a hundred acres, on condition that it should be worked by the able-bodied unemployed under their charge. For three years the Board are to have the free use of the land, and the right at any time during that period to purchase the same from him for the sum of £2175, the original cost to Mr. Fels. At present all the Laindon colonists are housed in corrugated-iron buildings on the estate; but as the men have been so well-behaved, and have proved themselves such willing workers, it is being mooted that they shall be paid a weekly wage of some thirteen shillings, and be quartered as lodgers in the cottages of the surrounding district. If this were done a saving of about two shillings per head would be effected, and the men would gather the fruit of their labour. Officialdom says the law will not permit; but why not let the "hass" be beaten until he mends his pace? One man's individuality is mainly responsible for the colony's striking success in "man-making" — that of its superintendent, Mr. John Clarke, a born organiser. Everything goes at the colony with almost Kitchener-like precision, from the constructing of a reservoir to the building of chicken-houses. In the making up of little gangs to carry out the varied kinds of work, he chooses the men most carefully, knowing that whereas "Jack" and "Tom" may work together in harmony, "Bill" and "Henry" will in all probability do little or nothing. Then, again, he varies the work as much as possible, so that a man may not be sickened with the monotony that would arise from sticking an eight-inch fork into a hard clayey soil week after week, month after month. The favourite job of the colonists has been the making of the reservoir, as the gang is larger and therefore livelier than any doing field-work, and there is always the pleasure that comes from construction. These men have the pride of builders upon them and feel themselves more than a cut above the others.

Poplar Labour Colony reservoir construction, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony, reservoir construction, 1904.

Problems soon arose, however. There was no high wall surrounding the colony site and as a result men regularly slept out, begged, and frequented local public houses. The land, of an areas which would normally have required only four labourers for its cultivation by plough, was instead dug over and over by the men with spades, a practice which became as futile as the work it was intended to have replaced.

The experiment was ultimately judged to be a failure, with discipline being poor and little labour being performed by the inmates. The initial colony scheme ended in 1912. However the site was retained by the union and continued to provide accommodation for able-bodied male paupers.

In 1930, control of the establishment passed to the London County Council who retained the site, renamed Dunton Farm, for the accommodation of up to 150 older men. The LCC improved and extended the buildings and installed electricity. Stock, arable and fruit farming were carried out by the inmates, and training was provided in most branches of agricultural work, and also in kitchen gardening, poultry keeping, carpentry, and estate repair work.

Langley House Receiving Home

In about 1903, a property at 54 East India Dock Road was acquired and adapted as a receiving home for around a hundred children. The premises became known as Langley House. The building no longer exists.Poplar Training Schools, Hutton

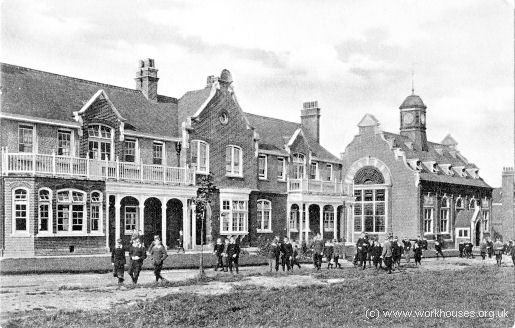

In 1906, the Poplar Guardians erected a training school for around 700 children on a 100-acre site at Hutton in Essex. The land cost £101 an acre but lacked a water supply, drainage system and road access. This, together with the ornate design of some of the buildings, contributed to the unusually high final cost of the project (£184,280) which was one of the last of its type to be erected. The school opened its doors in February, 1907.

Poplar Training Schools site, 1920.

Poplar Training Schools from the south, 1920s

© Peter Higginbotham.

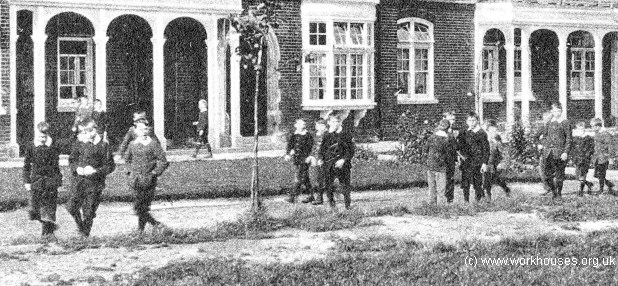

The buildings, designed by the partnership of Holman and Goodman, took the form of a "cottage homes" village arranged a large green. Five double cottages for boys stood at the west of the green and five for girls at the east side.

Poplar Training Schools boys' cottages from the south, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools boys' cottages and dining hall from the south, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools boys' cottages detail, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools girls' cottages from the south-east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools girls' cottages detail, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A large complex of buildings at the north side of the green included a swimming bath, gymnasium, boiler house and water tower. At the south side was the administration block, and a training base for girls learning laundry work. At the south-west of the site were the school and superintendent's house.

Poplar Training Schools administration block, c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the middle of the boys' cottages stood an elaborately decorated dining hall (the girls prepared, served and meals in their own cottages as part of their domestic training). The single-storey building was surmounted by a bell tower. A terra-cotta frieze adorns the top of bay at the eastern side, one depicting St Leonard — possibly a reference to the Shoreditch who may have made use of the school. The interior was equally ornate — during a House of Lords debate on 4th May, 1906, concerning the alleged extravagance of the Guardians, one speaker remarked that 'the beams in the Dining Hall would do credit to an English Cathedral.'

Poplar Training Schools boys' homes and dining hall, c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools boys' dining hall from the south, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools boys' dining hall from the south-west, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools boys' dining hall frieze, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

The main school building was a large T-shaped structure with a large hall in the central wing to the rear.

Poplar Training Schools main school building from the south-east, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools main school building from the south-east, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools main school building from the north-east, c.1920

© Peter Higginbotham.

Poplar Training Schools main school building from the north-east, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

A porter's lodge was located at the entrance to the site at the south.

Poplar Training Schools lodge from the west, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Forty acres of the site was used as a farm where children worked to provide much of the school's food. Five hundred fruit tress were planted, some of which survive in the gardens of houses on Colet Road in Hutton.

There school had no uniform as such. Boys wore knickerbockers and tunics, or trousers and jackets, while the girls wore blouses with frocks, jumpers and print pinafores.

Boys' were trained in small 'shops' in the trades of boot making, tailoring, carpentry, baking and gardening. They were also encouraged to learn a musical instrument and join the school military band which was of a high standard. Older girls trained as domestic servants and were taught cookery, needlework and laundry skills.

On 14th May, 1919, the school was visited by Queen Mary and Princess Mary. They watched a physical drill by the younger children and toured classrooms and training shops before enjoying a musical performance by the school band and choirs.

The school had its own school magazine which in one issue contained the words to the song The Poplar Tree by R. Jones.

Oh! the Poplar Tree stands straight and true

Like a sentinel on duty,

And every twig slants upward too,

For every twig's on duty.

That's a hint for me

And a nod for you,

For I'm a twig

And so are you.

So sing with me to the Poplar Tree

That stands up straight on duty.

Chorus:

One and all, one and all,

Twig and Trunk and Root and all,

Together, together,

In every weather,

Storm and trouble and toil and moil,

The Poplar Tree stands sturdily,

With its roots sunk deep in English soil.

Oh! the Seaman's Oak and the Bowman's Yew

Have shared in England's Story;

For they were stout and tough and true

And truth is a nation's glory.

So the work for me

Is to keep her true,

As stout as Oak,

As tough as Yew.

And straight and free like the Poplar, Tree,

For she pledges me her glory.

Homeland and far land,

Dark face and white,

Land of Poplar, Palm or Pine,

Dark sky or bright,

Old time or new time,

Calm and battle and strife,

Truth is clear,

Honour's dear,

Right's right.

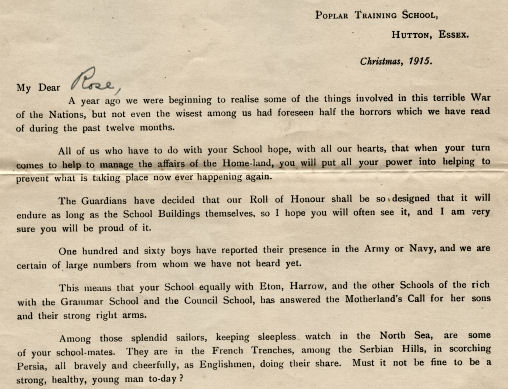

During the First World War, the Duke of York's Royal Military School at Dover School was evacuated to Hutton and occupied the girls' part of the site, with the Hutton girls being relocated to other properties including an old house called "The Meads". For some years, the School's superintendent, William Dean, wrote a Christmas newsletter to former pupils. Below is the beginning of the 1915 letter, when the war was beginning to take its toll on the nation's young men.

Poplar Training Schools Newsletter, 1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

You can also view the full 1918 Newsletter which lists all the former pupils who had died during the war.

In 1930, control of the school passed to the London County Council. In the 1950s, the schools' farmland was sold. In the 1970s, the school was taken over by the Inner London Education Authority. In 1974, following changes in the law relating to children in care, the school's intake fell considerably. The main school building was sold to Essex County Council for use as an adult education centre. By 1980, only 40 children were still in residence and the home was closed. All the children were placed in foster homes, with the last child leaving in March 1982.

Most of the buildings have now been demolished with the exception of the school, the porter's lodge, and the dining-hall which was restored in 1990-91 and is now used as a community hall.

The Poplar Union Scandal and Inquiry

In 1906, a growing catalogue of complaints, together with what was viewed by many local ratepayers as the Guardians' increasingly extravagant expenditure, led to the holding of a public inquiry by the Local Government Board into the running of the union.

Figures produced during the proceedings showed that between 1894 and 1904, poor relief expenditure in the Poplar Union had risen from £34,698 to £60,142. This was coupled with a rise in the average number of indoor paupers from 2,623 to 3,677. The overall population of the union over the period had not risen, and other comparable unions had not shown a similar increase in pauperism. From early 1904, out-relief had been dispensed without the imposition of a labour test — the requirement to perform work. Within a few weeks, the weekly cost had risen from £88 to over £300. Relief had also been given to the over-sixties without any enquiry as to the earning of other family members, effectively using poor-relief as a form of old-age pension.

The level of comfort for inmates in the workhouse was revealed to be superior that of a typical working labourer, with rations of beer issued to inmates amounting to over 200 pints a day on occasion. Members of the Board of Guardians, and also tradesmen supplying the union, were reported as often taking meals and drinking with the Master at the workhouse and, contrary to normal practice, contracts were regularly being awarded to suppliers who had not tendered the lowest price. In the case of one milk contract, over £200 would have been saved if the lowest tender had been taken. In some cases, bribes had been paid by suppliers to secure such contracts.

The workhouse Master, who had resigned by the start of the inquiry supposedly due to ill-health, was shown to have been neglecting his duties because of an relationship he had been conducting with a former nurse at the workhouse. Because of this, inmates performed virtually no work and discipline in the workhouse was said to be non-existent.

Criticism was also made of the expenditure on the new union schools, and the unnecessarily high standard of construction and materials, such as the use of teak for banisters. The Laindon labour colony, too, was denounced as as a social and economic failure. The cost of maintaining men at the colony was wastefully high, amounting to seven shillings for the man himself, plus up to ten shillings out-relief for his wife and family.

Despite the many criticisms, the two leading lights of Poplarism, Will Crooks and George Lansbury, were largely exonerated.

The Poplar Rates Revolt

There was a resurgence of Poplarism following the election of Poplar's first Labour council in 1919 when George Lansbury became mayor. The new borough council embarked on a programme of social reform, which included paying council employees wages that were above the market rate. The Board of Guardians, too, despite an increasing level of unemployment, operated a generous out-relief policy. By 1921, the cost of these measures was such that the borough council refused to pay its annual rates levy to bodies such as the Metropolitan Asylums Board and London County Council. The borough argued that London's rating system put it at a disadvantage - the lower values of property in Poplar meant that to raise a given amount of money, it had to charge much higher rates than would be required in a richer borough. After ignoring a court order to make the payments, thirty councillors were imprisoned. The protestors received considerable public support and were released six weeks later. Soon afterwards, the Local Authorities (Financial Provisions) Act was rushed through parliament to amend the capital's rating procedure in the way that Poplar had demanded.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- Poplar High Street workhouse holdings include: Admissions and discharges (1845-71, 1902-24, 1928-30); Births (1837-1914); Baptisms (18881-1939); Deaths (1860-1931); Creed registers (1844-1940); etc.

- Wapping branch workhouse holdings: Creed registers (1869-71); Deaths (1867-71).

- Forest Gate (later Hutton) schools holdings: Lists of pauper children (1869-1903); Admissions/discharges (1897-1932); Creed registers (1899-1932); Deaths (1869-99); Punishment register (1913-16).

- Forest Gate branch workhouse holdings: Registers of inmates (1908-15); Creed registers (1908-12); Deaths (1908-11).

- Laindon colony holdings: Registers of inmates (1904-25).

- Langley House holdings: Admissions/discharges (1903-40); Creed register (1903-15); Register of inmates (1929-40).

- General Holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1836-1930, with gap); Lists of pauper children (1850-75, 1884-1924); Register of emigrants (1907-13); Financial records (1837-1930); Staff records (1842-1930); etc.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Haw, G (1907) From Workhouse to Westminster: The Life Story of Will Crooks M.P.

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.