Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

Up to 1834

The first Nottingham workhouse was set up by St Mary's parish in 1723 on land between York Street and Mansfield Road. By 1808, the building had deteriorated and the parish began to plan for a new workhouse. Initially, a larger site on Dog Kennel Hill was considered, but eventually the replacement was built on the old site at a cost of more than £5,000.

In 1729, St Nicholas' parish erected a workhouse on Gillyflower Hill, at the east side of what is now Castle Road. In 1813, it was declared unfit for habitation and a large building at the bottom of Park Row was bought as a replacement. The old building was subsequently divided into tenements which became known as Jessamine Cottages and their location renamed Old Workhouse Yard. By the 1940s, the premises had become disused and were deteriorating. A plan to convert the building into a museum was unsuccessful and it was eventually demolished in 1956. The new People's College (now Castle College) was opened on a large site which included the location of the old workhouse.

Nottingham Workhouse Yard site, 1881.

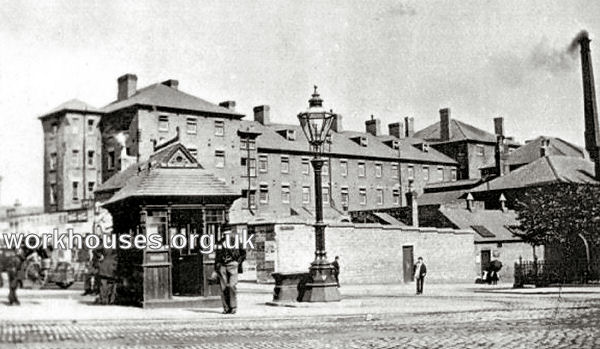

York Street workhouse from the west, Nottingham, 1890s.

St Peter's parish originally had a workhouse at the east end of Houndsgate. After this building was demolished, a new workhouse was built on the south side of Broad Marsh.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England, reported that:

Bill of fare: Breakfast—Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, milk pottage; Monday, Wednesday, Saturday, water gruel; Thursday, bread and gruel. Dinner—Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, broth, beef and potatoes; Monday, Wednesday, Saturday, cold meat, broth and potatoes ; Thursday, puddings and sauce made of water, flour, alegar and sugar. Supper-every day except Thursday, bread and beer; Thursday, bread, cheese and beer. The average weekly consumption per head is 4lb. meat 31 pints beer. About 70 stone of second flour, at 2s. 6d. the stone, are made into bread weekly. About 11oz brown bread are allowed each grown person for supper, and about 2/3 of a pint of beer. 5 pecks of potatoes, at 9d. per peck, are used daily on meat days. About a bush. oatmeal weekly. Children and sick persons are often indulged with puddings and flour hasty puddings. At Thursday's supper about 2¾. of cheese are allowed each adult, and a proportionate quantity to children. Certificates are not willingly granted, about 4 or 5 in a year. There are about 14 removals a year, of which one or two are contested. Several small donations amounting to about £80 a year, are distributed annually to such Poor as do not otherwise receive parochial assistance. The other parishes are burdened with Poor in nearly the same proportion. Some years back it was proposed to erect a House of Industry for all the parishes, but differences of opinion and discordancy of interest caused the scheme to fail. The rates which in 1795 were 4s. 4d. on houses, and 10s. on land, have risen rapidly in recent years. No satisfactory reason could be assigned, as the principal stocking manufacturers say the war has not materially affected them, as their chief export is to America. The rise is generally attributed to the high price of provisions, the scarcity of common labour, and the great number of soldiers and militia men's wives and families who have lately become burdensome to the parish.

In 1819, at a time of depression and high unemployment in Nottingham, St Mary's parish appointed Absalom Barnett as its full-time Overseer (Caplan, 1984). Barnett introduced a variety of new measures in the parish's treatment of the poor. There was an end to all wage supplements, allowances for large families, or the payment of rents. The unemployed were instead offered poorly-paid work including the cultivation of waste ground, stone-breaking and road-mending. Barnett also adopted the workhouse test with able-bodied unemployed being offered relief through entry into the workhouse, its capacity of 400 was soon exceeded and work again had to be offered instead. Barnett later gave evidence about his practices to the Poor Law Commission.

After 1834

The Nottingham Poor Law Union formally came into being on 6th July 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 24 in number, representing its 3 constituent parishes of St Mary (12 Guardians), St Peter (6), and St Nicholas (6). The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 50,680 comprising St Mary (39,539), St Peter (5,447) and St Nicholas (5,694). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1833-35 had been £11,150 or 4s.5d. per head.

Initially the new Nottingham union proceeded with enthusiasm to implement the new principle of denying out-relief to able-bodied applicants. Edward Gulson, the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner for the area, was able to report back to his London headquarters that the Nottingham Guardians were carrying "out your wishes in both spirit and letter more rapidly and cordially than any other Board of Guardians I ever saw." Credit for much of this lay with one Absolem Barnett, who simultaneously held the posts of union clerk, relieving officer, and workhouse master. Such support was greatly encouraging for the Poor law Commissioners, as Nottingham had much in common with the Lancashire and Yorkshire textile districts which were next in line for bringing into the new Poor law system.

The new Nottingham Union took over the existing St Mary's parish workhouse at the west side of York Street. The workhouse at this time could accommodate 520 inmates. However, this was not sufficient to cope with the effects of a slump in the hosiery trade in 1836. Additional premises were rented for accommodating children and old men, and the former St Nicholas parish workhouse was pressed into service as a hospital. This brought the total accommodation up to almost seven hundred.

The slump continued through 1837 and an Assistant Poor Law Commissioner was despatched to assist the Guardians in trying to deal with the crisis. The Poor Law Commissioners reluctantly decided to suspend the rules forbidding the giving of out relief to the able-bodied. A public relief fund was also established in the city and raised £4,000 allowing hundreds of adults and children to be fed each day at the workhouse. However, when the fund ran out, the Poor Law Commissioners finally gave way and allowed, temporarily at least, out-relief for the able-bodied in return for manual labour such as stone-breaking.

Economic conditions improved in 1838, leading to a fall in numbers in the workhouse, and the re-imposition of the prohibition on out-relief to the able-bodied. However, a further slump in 1839 led to the Guardians requesting the dissolution of the union and a return to the former system of management by the individual parishes. The Poor Law Commissioners refused this request but again lifted the ban on out-relief to the able-bodied, and allowed it to be offered in return for outdoor labour.

By now, the Commissioners had firmly decided that the long-term answer was for Nottingham to erect a large new workhouse able to house at least 800 inmates. The Guardians grudgingly accepted this proposal and, despite considerable public opposition, construction work had begun by the end of 1840. The following March, a new Board of Guardians with an anti-Poor Law majority tried to delay completion of the workhouse but were eventually forced to go ahead with it. The result was that the union, which felt itself saddled with a workhouse much bigger than the city needed, thereafter offered the absolute minimum of co-operation with the central authorities. In a few short years, Nottingham had been turned from a model union into a centre of resistance to the New Poor Law.

A picture of life in the old Nottingham workhouse is given by James Orange in 1840:

Supper at half-past five o'clock for the children, which consists of an unlimited supply of bread and milk porridge, as at breakfast. After these are withdrawn to play, the adults come and take their places, when, as in the morning, there is reading the scripture and prayer, before supper, after which they amuse themselves in their proper apartments, and at eight o'clock the day rooms are locked up for the night. Then those whose business it is, clean the day rooms ready for the morning.

In the dietary of the house, we have specified the hours at which their three daily meals are taken, the quantity of bread each at breakfast and supper, and the unlimited supply of good wholesome porridge have been already described, we have therefore only to notice of what their dinners consist. Sabbath-day, beef, seven ounces each for men, and six ounces each for women. No bread is allowed with this meal, but instead of weighing the potatoes, they have an unlimited supply.

Monday: Irish-stew made from the bones of the meat used on the previous day, with an additional quantity of fresh meat. No bread is allowed to this dinner, except what may have been reserved from a previous meal; instead of this being served to them by measure, the stew, which is good, is served without limit.

Tuesday: pudding, made of suet and fine flower, mixed with water; sixteen ounces for each man, and fourteen ounces each woman.

Wednesday: broth, in which carrots and other vegetables are boiled, to give It an agreeable flavour. Of this they have an unlimited supply, and an allowance of bread, seven ounces to a man six to a woman.

Thursday: this is a meat day again, served in the same manner and proportions as on Sabbath-days.

Friday: peas soup, of which there is no limit as to quantity, but as the peas are to serve the purpose, there is no allowance of bread except what they may have saved.

Saturday: broth and bread, in the same manner as on Wednesdays.

Religious Instruction; reading the scriptures and prayer, morning and night every day, and though no salaried chaplain has hitherto been appointed since the union was formed, yet the duties of the office have been uninterruptedly and efficiently supplied by the voluntary services of pious Christians, who perform two full services every sabbath; in the afternoon by dissenting ministers, and in the evening according to the formularies of the establishment, by a pious lay churchman. Well-conducted inmates are allowed to leave the house on Sunday mornings, to attend their respective places of worship; and in the afternoons of three or four days in the week, some of the aged persons are let out to visit, their friends, &c. There is a good library of books, religious, moral, and entertaining, for the use of the inmates who have the ability and are disposed to read.

Appearance. The cleanly and healthful appearance of the children is really delightful, which may be accounted for by the orderly discipline to which they are subjected; healthful exercises, plenty of wholesome food, warm clothing, particularly good shoes and stockings, in which respect they enjoy superior advantages to the generality of children of the poor. The appearance of the women is clean and becoming, and so is that of the men; and though they are generally well fleshed, there is a sickly paleness spread over the countenances of most of them, which probably originates in the crowded state of the house, and gives them the appearance of felon prisoners, undergoing a lengthened confinement in a cell, and look emaciated for want of fresh air.

That which more than any other thing interested us in this comfortless place, was the college of little cobblers. Here were ten of the bigger lads, with new leather aprons, sitting on the end of little shoemaker's stalls, learning the art and craft of shoe-making, some mending, and others making new shoes and laced boots for the various members of the establishment. Though none of them have been long engaged in acquiring that useful and necessary art, on examination, we found the work executed in the neatest manner, so as to induce the expectation that in time they will be able to execute these necessary and elegant articles in the first style of the art, and thus supply to the next generation one of the very few instances in which pauperism may issue in a blessing.

The food is prepared in a large kitchen, on the east side or the women's yard, and adjoins the governor's house, All the cooking is done by steam, which is very commendable, as it obviates the occurrence or any accident by fire, Under the kitchen are very deep spacious cellars, which constitute the boiler house and provision stores. North or the kitchen on the same side, are the wash- house and laundry, which are much too small for the business that is done in them, and must be injurious to the health of those by whom it is performed. The rooms over these constitute the store-house for linen, which is always kept clean and aired. West of these, constituting the north end of the establishment, are the brewhouse, fever room, and hospital for the women; all that can be said in their favour is, they are exceedingly clean, but low, contracted, and gloomy receptacles, unfit for the abode of persons in health, much less of those who are bowed down beneath the pressure of disease. Adjoining the west end of these, in a southern direction, is the new and best parts of this heterogeneous mass of building, but it is comparatively small, and is divided into day and sleeping rooms for the women, and utterly inadequate for the numbers crowded in it. South of these is the hospital for the men, Here there is one good room over the office, but to attain the other two, another flight of steps has to be ascended, and you enter two attics, which are so low that a man must stoop as he passes under the beams or enters the doors. Here the languishing inmates lie in beds exposed to all the variable changes of weather, inseparable from such rooms. We will not attempt to describe the shameful hovels in which the men and boys are crowded together, but when we recollect these houses are the unavoidable legal receptacles of the poor of all classes, from helpless infancy to extreme old age, how important to the poor, how interesting to the public, to devise means of maintenance and, instruction calculated to issue in beneficial results. but how is this sought to be obtained?

In the Nottingham house are presented shameless profligates in intimate association with inexperienced and unsuspecting childhood; it is a family in which deserted infancy; destitute youth, pauper manhood, worn-out age, wasting sickness, mental imbecility, and bodily decrepitude, are all indiscriminately mingled together. No one hesitates as to the propriety of preserving lunatics and idiots from annoyance. It is not for one moment disputed that the aged should enjoy quiet, and the imbecile protection; that the healthful and able-bodied should. be really employed or that the young should be instructed by example as well as precept, and by suitable training be prepared to become useful and independent (self supported) members of society. Yet, obvious and important as are these duties, to discharge them in this house appears impossible. We are told, and it has never been denied, that the aged have little or no quiet; the able, no adequate employment; the vicious are not effectually restrained; the idle are not made to work; and, worse than all, the young. those on whose culture the future welfare of society is mainly dependant, are not trained in habits of industrious application; and moral instruction, so far from being enforced by example, is powerfully if not completely counteracted by the evil influence of vicious association.

This deplorable state of things is inseparable from a house so crowded and ill arranged, that effective supervision and extensive classification are equally impracticable and unknown.

The results, however disgraceful, are such as might be expected; young men alternating between a prison and the workhouse, and women of loose character inadequately restrained.

The premises used as nurseries and schools are separated from the workhouse by York-street ; thus situated they are practically independent of observation and control.

In 1840, despite intense local opposition, the Guardians decided to build a new workhouse accommodating 1000 inmates on a site at the east side of York Street. In 1841, however, a new Board of Guardians refused to send paupers to the new premises which were nearing completion. In September 1841, the Board applied to the Poor Law Commissioners for permission to re-open the old St Nicholas' parish workhouse to cope with growing numbers of paupers — this was refused. By November, conditions in the old workhouse had become extremely overcrowded numbers reaching a peak of 908 inmates. During this period, five children were said to have died because of the dire conditions. In one case, that of Robert Porter, who died from an inflammation of the chest, the inquest found that he had "been rendered more susceptible of disease, and less able to bear active treatment when labouring under disease, from having lived in certain rooms not adapted to the number of persons required to live and sleep therein." As a result, the Poor Law Commissioners despatched Harley Street Henry Hancock, a physician from Charing Cross Hospital, to conduct a thorough inspection of the premises, following which the capacity of the old workhouse was reduced to 240. This made it impossible for the Guardians to avoid using the new building.

Some extracts from Hancock's report on the old workhouse are included below.

...

There are 32 sleeping apartments for the men, for the most part ill adapted, dull, close, and badly ventilated.... No.25.—Measures 55 ft. by 8, and 6 ft. high. Contains 6 beds of which 4 are now occupied by 12 young men (3 in a bed). Twenty-eight young men latterly slept here (5 in a bed)... No.29.—Is a ward for infirm old men and is without exception, the most wretched place I ever entered. ...outside the wall are erected the common urinals for men and boys; hence this wall is completely saturated, so much so, that it has been found necessary to board up its inner side so high as the heads of the bedsteads placed against it. In this "den" 6 infirm old men constantly reside... it is dark, close, and dirty, and quite unfit for the residence of human beings.

...

The bed-rooms for women, eleven in number... No.10.—Is another room for infirm old women. It measures 29 ft. 6 by 12 ft., and 9 ft. 3 high. Contains 10 beds, occupied by 19 old women. This room is close and offensive from its approximation to the common privy; the smell of which it is attempted to destroy by chloride of lime. One of the inmates was in the agonies of death, and, as I understood, had been so for 2 days; she lay exposed to every one entering the ward.

...

There are 5 sleeping rooms for the boys; for the most part close, dirty, and too much crowded. Urinals are not allowed for these rooms, but in some are 2 large buckets, and in others a leaden sink erected in the corner of each.

...

Girl.—No.1.—This is not fit for a sleeping room. It is situated over the wash-house and very damp. Contains 7 beds, in which sleep 15 girls and one woman: 19 women and 6 children lately occupied this apartment, which at the time I visited it was damp and filled with steam.

...

Chapel.—This is likewise used as a dining-room. It measures 80 ft. long by 18 ft. wide, and 9 ft. 6 high for two-thirds of its length, and 18 ft. high for the remainder. It has no fire-place in it, and is very cold, damp, and dirty. The difference in temperature between this and the other day wards is very great, and the sudden transition from the close, confined atmosphere of the latter, to the cold damp air of the former, must be prejudicial, especially to the children and other infants.

...

There is no accommodation for washing; the only provision made is a trough placed in each of the male and female yards, at which the inmates wash, exposed to the weather, be it what it may, without even a shed to cover them.

...

Foul Wards.—In the same building are two rooms, very small, in one of which are collected 12 children suffering from porrigo, and in the other, which is over this latter, are four beds completely filling the room, occupied by four men suffering from the itch. It appears to be considered that cleanliness is not required in the treatment of this disorder. I should say it is as necessary as the unguents and applications usually employed; probably more so.

...

Day Wards. No.3.—Is the day ward for married men. I was informed by one of the Guardians present, that this room was known as the "Black Hole in Calcutta" from its crowded condition, being underground, and very dark and dirty. It measures 26 ft. by 17, and 8 ft. high. It contains 28 inmates at present, and has lately contained 40. The men told me it was usually so crowded that they could not sit down. It is used for six hours daily.

...

I do not consider the general condition of the children by any means healthy. Their flesh, especially that of the girls, is flabby, the abdomen large, and the tongue bearing evident signs of gastric irritation. A very large proportion of both girls and boys are of strumous habits, which, although not at present assuming an active form, still exists, predisposing them to disease, and rendering them unable to resist its attacks, or to bear the remedies necessary for their cure. These children require much more airy and better ventilated apartments than are at present allotted to them, and I would observe that during my experience as surgeon to one of the largest infirmaries for children in London, I never met with an instance in which so many children were collected in such offensive, close, and badly-ventilated apartments as those which they now inhabit in the Nottingham Union house.

...

...some conclusion might be arrived at as to the nature and extent of accommodation afforded in this building. It will at once be seen that it is far too crowded, even with its present numbers! What it must have been when it contained 910 individuals is too evident to require comment. The average space allowed to each in the male and female sleeping wards is not above half what it should be, whilst in those of the boys it is about 165 cubic feet, and for the girls about 131, instead of from 350 to 400, which I should say is the smallest quantity that can be calculated consistent with health and comfort in such an edifice as this, where the ventilation is so defective. The day wards are even worse, not averaging above a third of the necessary space. Judging, therefore, from these facts, and after deducting those apartments from which I have already recommended the inmates to be removed, they being unhealthy and unfit for occupation, from 230 to 240 is about the number which can with safety and comfort be accommodated in the Nottingham workhouse.

...

Finally, I would add, that in the preceding observations as to the dirty condition of some of the apartments, I do not at all mean to cast any reflection upon the master of the workhouse, as from what I saw I feel assured that everything is done by that officer for the comfort and cleanliness of the inmates that can possibly be achieved in such a house.

Hancock also inspected three of the other old Nottingham workhouses during his visit:

- St. Mary's workhouse (presumably an annexe to the building taken over by the Nottingham union) was reported as "...opposite the Nottingham workhouse, and is at present used as the day and night habitation of some of the girls of the Union, as has been already noticed in the report of the Nottingham workhouse, &c. It likewise contains four dirty rooms, each about 15 ft. square, used as casual wards, and in one of which was a girl with the itch."

- St. Peter's workhouse was "...situated near St. Peter's church, is a small building, at present occupied by a timber-merchant. It is quite unfit for a workhouse."

- St Nicholas' Workhouse was "originally built for the dwelling-house and manufactory of a hosier. One end and side look upon a fair-sized plot of ground, the others are next the street. That portion of the premises built for the dwelling-house is in a very fair condition: the rest is damp and dirty, and requires whitewashing and repairing. It is at present occupied as barracks for soldiers, and contains 29 rooms in all, besides two dirty outbuildings, now used by poultry. This building was lately the hospital to the Union. However, on an emergency it might prove useful, as, if properly cleaned, it is capable of containing from 80 to 90 persons, consistently with health and comfort.

The York Street Workhouse

The new York Street workhouse was also visited by Henry Hancock during his inspection tour at the end of 1841. His report, below, provides a detailed description of the new premises.

Basement.—On the basement are 10 rooms, intended for stores. One of these requires flooring, and the remainder the windows glazing; but in other respects they are complete, excepting furniture.

Ground Floor Centre.—In the centre are six rooms, consisting of master's rooms, general kitchen, and store-rooms complete, excepting shelves and furniture.

South Wing.—In the south wing are five wards, each measuring 30 ft. 8 by 17 ft. 1, and 10 ft. high, intended as day wards for men, infirm and otherwise, one measuring 32 ft. 6 by 17, and 10 ft. high, likewise for men, and two measuring 35 ft. 9 by 21, and 10 ft. high each, intended as day wards for boys, and now used as school-rooms for the girls and boys of the old house. All these rooms are finished, excepting furniture.

North Wing.—In the north wing are the same number of apartments of similar dimensions as those in the south wing. They are intended as day-rooms for the women and girls, with a nursery for the latter. Two of these require flooring, some whitewashing, and the whole fastenings to the doors and the windows, and fire-places fixing.

One Pair Centre.—In the centre are five rooms, with a water-closet : three of these are for lodging-rooms, and the remainder for stores. These are complete.

South Wing contains eight rooms of the same dimensions as those below. Two of these are intended as sick-wards for the men, but I would recommend that all the sick-wards be in the out-building, as it. is never advisable to have sick-wards in the very heart of a house of this description : four as sleeping-wards for the men, and two for boys. These rooms are all complete, excepting the door-fastenings.

North Wing is exactly the same as the South, with the exception of its being appropriated to the women and the girls.

Two Pair.—The rooms on this floor correspond to those below. They are complete, excepting the grates and door-fastenings.

Attics, Centre.—These rooms are the same as below, and only require door-fastenings.

South Wing.—There are three rooms opening one into the other, each measuring 38 ft. by 25 ft. 3, and 5 ft. 3 high. There are four windows in each of these rooms, placed opposite to each other, and the chimneys from the rooms below run up through these apartments, one on either side, and join in the centre, forming an archway. The aggregate length of these rooms is 114 ft. They are intended as sleeping-rooms for men. At the end are two rooms with square ceilings, each measuring 35 ft. 9 by 20 ft. 11, and 8 ft. 3 high. They are warmed by hot air, and are intended as nurseries for children. These rooms are complete.

North Wing is the same in all respects as the south.

The house is very dry, well ventilated, and the rooms lofty, airy, and spacious; but I would suggest, in the first place, that the men and boys be placed in the north wing, and the women and girls in the south, instead of the present arrangement; and in the second, that sliding doors be placed over the ventilators, that the ventilation may be regulated according to circumstances and the season of the year. These might be furnished with fastenings, and thus be completely under the control of the master.

The corridors and staircases are warmed by hot-water pipes.

In each wing are seven stone staircases, five of which terminate in the attics, and are so erected as completely to classify the apartments. The first landing-place on each staircase is furnished with a water-trough, having from four to six compartments, and supplied with hot and cold water for the daily washing of the inmates. The second floor is furnished with a bath on each landing-place. These will be enclosed by screens, and are well supplied with hot and cold water, as are also the sinks erected at the ends of the corridors on the first and second floors. Water-closets are erected at the foot of each staircase for the use of the inmates during the night.

OUT-BUILDINGS.

Western Aspect.—On the western aspect are the following buildings in various stages of completion, viz.:—

Bakehouse.—The bakehouse raised to about 5 ft., and the mill-house and capstan-sheds not so far advanced.

Cooking Room.—-The cooking room, measuring 28 ft. 6 by 18 ft. and 12 ft. high, fitted with 5 boilers and zinc steam-conductors; of the latter, one is incomplete, as are also two of the windows.

Scullery.—Fitted up with sinks, and supplied with hot and cold water, complete, excepting the doors, two windows, and the ceiling.

Chapel, &c.—The chapel and dining-room, a very nice room, measuring 76 ft. by 46, and 18 ft. high, is lighted by 13 windows, and warmed by hot-water pipes laid in the flooring. It is complete, excepting the floor, ceiling, and windows; the walls likewise require whitewashing. The tiles for the floor are now in the room.

Wash-house.—The wash-house, measuring 36 ft. 6 by 20 ft. 2, and 14 ft. high, complete, excepting the ceiling and wash-tubs.

Laundry.—The laundry, measuring 33 ft. 6 by 19 ft. 2, and 14 ft. high, complete, excepting the ironing-stove, door, floor, windows, and whitewashing.

Drying-Stove.—The drying-stove, measuring 37 ft. long by 1.1 ft. wide, and 7 ft. high, heated by boiler below, and complete, excepting floor and window.

Girls' School Room.—At the north end of the western aspect is the girls' school-room, lighted by six windows, and warmed by two fireplaces. It is incomplete as to its floor (wood), ceiling, window-frames, door and fire-places. Under the chapel are 4 rooms, each measuring 34 ft. 6 by 13 ft. 8, and 7 ft. 6 high, 3 requiring flooring., the whole doors, and the windows glazing. There are likewise 2 rooms for the paupers' clothing, which require fire-place fixing, floor, door, and windows glazing.

Cleansing Wards.—There are 2 cleansing wards, measuring 12 ft. 9 by 8 ft. 3, and 7 ft. 6 high. They are complete, excepting the floor, door, and the windows being glazed.

Receiving Rooms.—There are two receiving rooms, each measuring 34 ft. 3 by 13 ft. 9, and 8 ft. 3 high. One of these is complete, the other wants flooring, windows, doors, and fire-place.

Boiler.—A very large boiler is erected in the west yard, which supplies the whole building with hot water. It requires a shed over it, as it is at present preserved from the weather by merely a temporary covering. Next to this is the foundation of another boiler, not as yet fixed.

At the south end of the west yard is a range of buildings, measuring 52 ft. long, consisting of privies and 2 wards, over which it is intended to erect 4 wards for infectious diseases; only the skeleton of the lower building is at present erected, and I should think that, with some alteration as regards the privies, this would be a very advantageous situation for the male sick-wards generally.

At the northern end of the west yard is another range of building 72 ft. long, now appropriated as coal-sheds; it is as yet a mere skeleton, over which it is intended to erect 5 wards for infectious diseases, syphilis, itch, &c. If the coals were removed to some of the cellars in the house, this building might be much more usefully employed as general sick-wards for females.

The following is merely the shell covered in:—

Entrance from York Street.—On the left of the passage on the ground floor are the waiting and relieving officers' rooms. On the right, the Dispensary, waiting and consulting rooms. On the first floor is the board room, clerks' and waiting rooms. Over these are rooms not appropriated. Behind the board room are the porter's sitting and bed rooms, over which is a fire-proof room for books and papers.

Eastern Aspect.—At the southern extremity are 3 yards, extending to Datchet-lane, for the men. Of the walls separating these yards, one is complete, excepting the coping; one is nearly up, but the other two have not progressed beyond their foundations. A privy is erected in each of these yards for the use of the inmates during the day. It is intended to build 3 similar yards, &c., for the use of the females at the northern extremity of the building. Between these two sets of yards a large space of ground will remain, which will serve as a carriage-drive to the house.

At either end of the building likewise, is a yard, the one for the boys, the other for girls, in each of which is placed the school-room.

I beg to recommend that a strong circular swing be erected in each of these spaces, and that the girls be further supplied with skipping-ropes, and the boys with bats, traps, and balls, to promote exercise, and the development of their muscles, which will tend in a great degree to improve their health.

In conclusion, I have also to recommend that, should this building be occupied, some of the unappropriated rooms be set apart for the instruction of the boys in useful trades, such as shoe-making, tailoring, carpentering, basket-making, &c. &c.;

Summary.—Considering these houses in regard to the relative advantages which they offer as habitations for any large body of individuals, whether paupers or otherwise, it is evident that no comparison can be drawn between them. The new house, when completed (which it may be in a month or six weeks, if required—in fact the house itself may be used as soon as aired), will afford every convenience and comfort that can reasonably be expected in an establishment of this description. It contains dry, airy, well ventilated, well proportioned rooms, and possesses every facility for complete classification, whilst it affords ample space for air and exercise.

Although from its superior arrangements this house might contain more inmates in proportion than the others, still, upon the same calculation, it would accommodate from 880 to 900 persons.

The location and layout of the York Street workhouse are shown on the 1881 map below.

Nottingham York Street site, 1881.

On 7th November, 1861, an inquest was held on the body of plumber George Newton, 39, who had met his death while working at the workhouse. Newton had gone down a well in the workhouse wash-up room to saw a suction pipe. He had pulled on the rope for a light, which was let down to him but soon went out. A rope being used to pull Newton up from the well then went slack. Another man named went down the well, which was believed to be 36 yards deep, but his light also went out and he was drawn back up. A man named Sharp then descended with a lantern and, near the bottom, found the deceased with his legs fast in a ladder and his head hanging downwards. Sharp's light went out but a rope was let down to him and he tied it around the deceased's legs to pull him up. Sharp told an inquest that he had found great difficulty breathing in the well and had felt a dreadful sleepy drowsiness, almost as if he were drunk. It was said that Newton had lit a fire in the well the previous day to try and clear it.

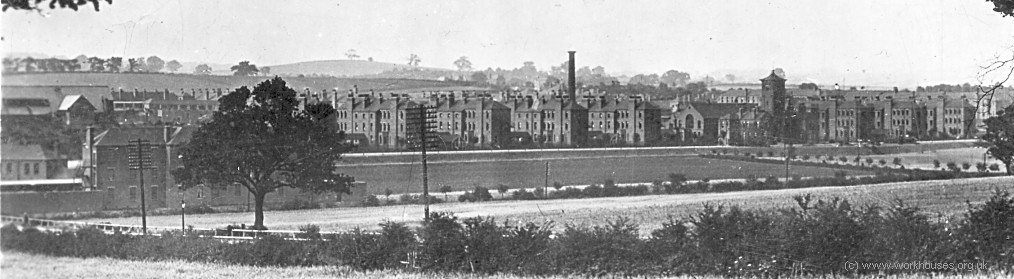

York Street workhouse from the west, Nottingham, 1890s.

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. Following a visit to Nottingham, the commission's report included a number of criticisms and recommendations. It was noted that there was no separate infirmary but that the sick wards were located in a section of the main workhouse, with surgical and lock [venereal] cases in a separate and more modern block to the front of the building. At the time of the commission's visit there were 210 patients in the male sick wards, 160 in the female wards, and 158 in the surgical block. Two trained male nurses covered all the male patients in the sick wards and surgical block. On On the female side there were three trained nurses, including the midwife; two of them tended the 160 beds in the hospital, with the third placed in the surgical block. One night nurse was on duty in each wing, assisted by a number of pauper inmates. The report concluded that "nursing was carried on under great difficulties, very crowded wards, a lack of appliances, an insufficient staff, supplemented by pauper help, no day rooms... The quarters provided for the nurses are cramped and uncomfortable; they have no mess room or recreation room, and their bedrooms are too close to their work." The commission's main recommendations were: the building of a new infirmary, the substitution of female for male nurses, an increase in the number of the nursing staff, with the complete abolition of pauper nursing; the provision of an ambulance for the removal of the sick; and a more varied diet for the infirm. Further details are available in the full report.

As it transpired, the York Street workhouse was demolished in 1896 to make way for the building of the Victoria Station. Its replacement was built in 1898-1903 on a site at Bagthorpe adjacent to the city isolation hospital and sanatorium which had been erected ten years earlier. The union was forced to vacate the York Street in July 1896 and was faced with the problem of finding temporary premises for housing up to 1,000 inmates for several years. The answer was provided by the conversion of empty lace-making factories on Great Freeman Street and on Beech Avenue in Forest Fields.

The Forest Fields Temporary Workhouse

One interim workhouse was set up in a former lace factory on Beech Avenue in the Forest Fields district. Included in the facilities was an iron-built isolation hospital which comprised an entrance lodge, administration block, two blocks for scarlet fever, one for "certain" diseases, one for smallpox with an annexe, a wash-house block, a laundry and disinfector, and a block for stables, mortuary and sheds for ambulances, etc. The ward blocks were each lit by two "Wenham" gas lights and linked by a corridor.

Nottingham Forest Fields workhouse site, c.1900.

Nottingham Forest Fields workhouse with isolation hospital (right) from the west, 2008.

© Penny Gallon

After the opening of the new Bagthorpe workhouse, the Beech Avenue site passed into the hands of Newball & Mason (manufacturers of fruit essence and vinegar) who sub-let space to various lace makers, Jacquard card punchers and printworks. It then became known as the Maville works, now occupied by Birkin's Textiles.

A nearby house at 59 Beech Avenue was used as one of the union's children's scattered homes.

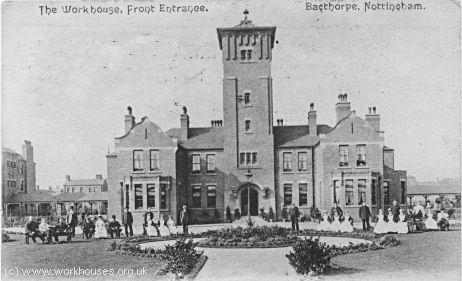

The Bagthorpe Workhouse

The Bagthorpe workhouse, designed by local architect Arthur Marshall, accommodated 1791 inmates. It had its own infirmary with 610 beds for the general sick poor plus 250 beds for 'imbeciles'. Its total cost was £273,000 of which £38,513 was recouped from the sale of the old premises.

Nottingham Bagthorpe workhouse from the south, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham

Nottingham Bagthorpe workhouse staff and officials, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham

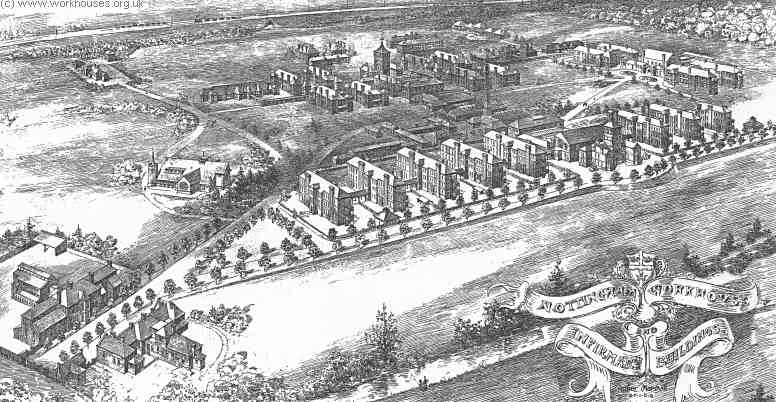

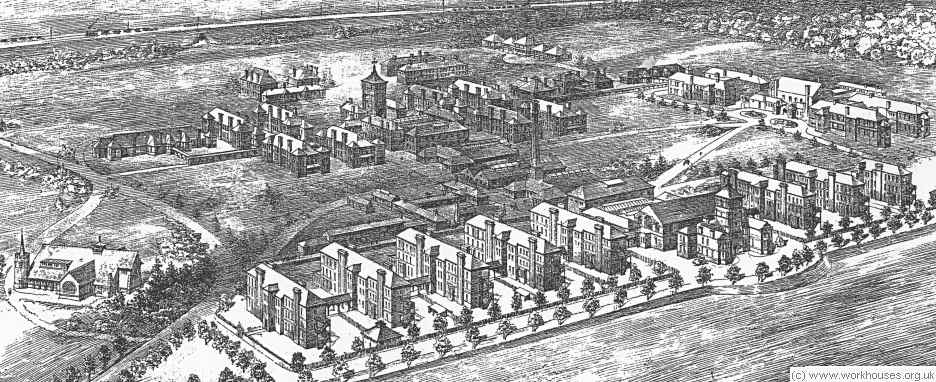

The new workhouse was built on the then popular pavilion plan, with a number of linked separate blocks. The layout of the site is shown on the 1913 map below:

Nottingham Bagthorpe site, 1913.

Nottingham workhouse — architect's bird's-eye view from the south-west, 1898.

© Peter Higginbotham

Nottingham workhouse — architect's bird's-eye view detail, 1898.

© Peter Higginbotham

Nottingham workhouse from the south-west, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham

The main accommodation blocks were at the south of the site, with an administrative block at the centre. To its rear were kitchen and dining rooms. The separate infirmary lay at the north of the workhouse.

Nottingham administration block from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

Nottingham laundry, kitchen and dining-room blocks from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

A cluster of buildings lay at the south-west entrance to the site, presumably these would have included a porter's lodge, receiving wards and a vagrants' block.

Nottingham entrance block from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse included a labour test house and labour yard which may also have been part of the entrance complex. The Test House provided tools and appliances to test the willingness to work of those able-bodied poor-relief claimants unable to find employment. In return for a day's work such as stone-breaking, they would receive food and a small amount of money. A yard enclosed by single-storey sheds still (2001) exists at the south-west of the site.

Nottingham labour yard(?) from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse chapel, a building with an attractive and unusual design, stood at the west of the workhouse.

Nottingham chapel from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse also contained a children's block but this was only for infants, with the policy being to foster out older children.

During the First World War, the infirmary cared for military patients which were brought in to a specially constructed railway siding at the north of the site. A postcard (below) of the infirmary in about 1915 includes the message from the sender, presumably a nurse at the hospital:

Nottingham infirmary entrance from the south, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse later became Nottingham Poor Law Institution then in 1937 was renamed Valebrook Lodge. The infirmary, originally known as Bagthorpe Infirmary, was called City Infirmary from 1930-37, then City Hospital. After the inauguration of the National Health Service in 1948, the workhouse section of the premises was initially known as City Hospital South. In 1951, it became Sherwood Hospital and provided accommodation for chronic cases until 1983. Most of main workhouse buildings no longer exist but the administrative block, chapel, and other surviving buildings now form part of Nottingham City Hospital.

Training Institution, Radford

In 1880, the adjacent Radford Union was dissolved and its member parishes absorbed by the Nottingham Union. The former Radford workhouse building was taken over by the Nottingham Union for use as a school and Industrial Training institution. In 1910, it could house 206 inmates.

Nottingham schools site, 1913.

Girls at the establishment were trained in domestic work. At the age of 14 to 16 the children were placed out in suitable employment with tradesmen and others in the area.

The Radford Training Institution premises were demolished in 1961.

Scattered Homes

The Nottingham Union operated a number of scattered Homes for pauper children. The locations included: 31 Addison Street; 4 Alberta Terrace; 59 Beech Avenue; 1 Ben Street; 317 Castle Boulevard; 9 Church Drive; 20 Gorsey Road; 82 Gregory Boulevard; 174-176 Radford Boulevard; 449-451 Mansfield Road; 102 Robin Hood's Chase; 5, 9 & 10 Victoria Villas, Sneinton. In 1924, the total capacity of these was 190 places.

There was also a Receiving Home on Norton Street where new admissions spent a probationary period and received a medical examination.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Nottinghamshire Archives and Southwell Diocesan Record Office, County House, Castle Meadow Road, Nottingham NG2 1AG. Holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1883-95); Admissions and discharges (1856-1920); Deaths (1851-2, 1861-2, 1864-85, 1890-1926); Creed registers (1881-1942 with gaps); etc.

Bibliography

- In the Shadow of the Workhouse by Maurice Caplan (1984)

- Bagthorpe to the City — The Story of Nottingham Hospital by James MacFine (Nottingham Health Authority, 1984).

- History and Antiquities of Nottingham by James Orange (1840)

Links

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to Penny Gallon for information on the Forest Fields workhouse.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.