Brighton (Brighthelmstone), Sussex

Up to 1834

Early poor relief in Brighton (or Brighthelmstone as it was formerly known) began in the early 1600s with the erection of some almshouses on the site of the former chapel of the Convent of Saint Bartholemews. By the early 1700s, the almshouses had become uninhabitable. Increasing numbers of poor around this time, compounded by a fishing war with continental fishermen, led to substantial increases in the town's poor rate.

The Market Street Workhouse

Taking advantage of Knatchbull's "Workhouse Test" Act of 1723, a new workhouse was erected as part of a new complex of buildings, again on the Saint Bartholemews site at the west side of Market Street. As well as the workhouse, the new buildings included a two-storey, gable-fronted Town Hall (where the town scales were located) and a dungeon (known as The Black Hole). The workhouse could accommodate up to 35 paupers and included a kitchen, workroom, pantry, brew-house, bedrooms and two cellars. Its inmates included the town's sick, aged, and impoverished children, who in addition to performing other poorhouse tasks, were expected to make their own clothes and prepare their own food. The new workhouse, whose construction had been dogged by escalating costs, opened in about 1730 and had almshouses added in about 1733.

In the 1740s, inmates picked oakum, and during winter months inmates collected and crushed oyster shells in a large iron mortar. The resulting compound was sold for fertilizing land and lawns, and for constructing paths in parks. In 1779, they were also employed making mackerel nets for sale. When the poorhouse Commissioners became responsible for maintaining local highways, paupers were reported to have been harnessed by ropes to muck and water carts and used as town scavengers removing animal dung and refuse from the streets.

In 1777, parliamentary report recorded that Brighthelmston had a workhouse that could accommodate up to seventy inmates.

In 1790, advertisements were placed for a new Governor, who was required to be a single man of good character in his forties. In the same year, town butchers were requested to submit fixed prices for meat and suet, and grocers and mealmen to do likewise for wheat, flour, cheese, butter, malt and hops, oats and peas, candles and soap and coal. Some idea of the poorhouse uniform can be gained from the schedule of goods given to the town drapers — quotes were asked for:

Women & Girls Check for aprons and handkerchiefs

Dowels for shifts

Yarn for stockings

Linen for round frocks

Straw for hats

Men & Boys' Blue Honley

Felt for hats

In the early 1800s, the Market Street workhouse had been enlarged to accommodate around 150 inmates who now wore brown uniforms. The workhouse was often full, and others in need of shelter, were placed in accommodation provided by a Mr. Rice (also a workhouse administrator) who charged the parish the rather high sum of four shillings per person per week. It was also poorhouse policy that orphaned or deserted children could be placed to learn a trade with local businessmen. The meaning of the word 'local' was sometimes rather stretched — in 1805, a large group of children from the Brighton poorhouse were dispatched to Lancashire to work in the cotton mills there.

In 1810, Brighton parish became incorporated under a local Act and responsibility for the workhouse passed to a board of thirty Directors and Guardians of the Poor. One of the board's first tasks was to try to make the poorhouse diet more economical by reducing the consumption of bread (an expensive commodity during the post-Napoleonic period) and substituting rice or herrings in its place.

The Church Hill Poorhouse

In 1818, the Guardians decided that a new workhouse was need to cope with increasing numbers. In 1820, a nine-acre site was purchased for £1,400 at the intersection of Church Hill with a minor road which led over the Devil's Dyke to join the road to Henfield and Horsham. A further £10,000 was allocated for the new building which was designed, after much competition, by London architect William Mackie. The building work was carried out by John Cheesman, a member of an extensive family of local builders, carpenters and manufacturers of cement. The crude foundation stone, laid in 1821 by the Revd D Carr, the Bishop of Chichester, was also provided by Cheesman. It measured some 24 inches by 18 inches by 10 inches and had been dug up on the site.

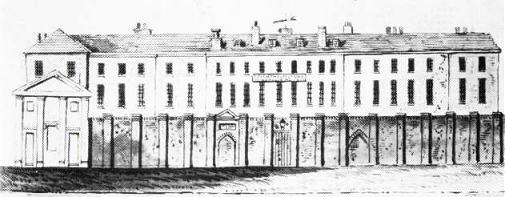

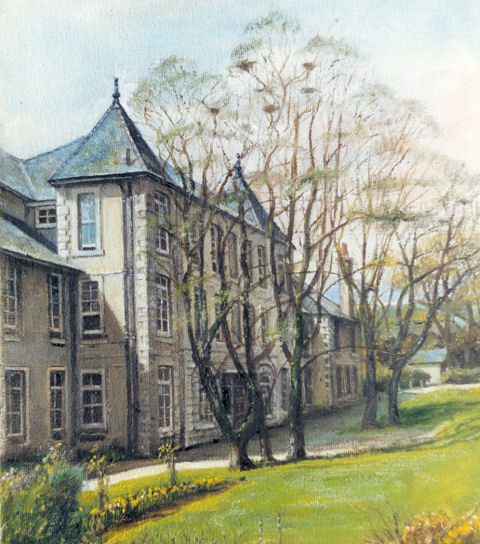

The new building had an 'H' shaped layout, which divided the workhouse into sections 'in order to class its inmates in the most regular manner.' Each internal area had access to a yard and the central section was for the workhouse administrators. The main frontage, shown below, was 191 feet long.

Brighton Church Hill workhouse, 1862

The inscription over its main door read:

Brighthelmstone Poor-house, Erected AD., 1821,

Vicar, Rev. R. J. Carr, D.D.

Churchwardens Edward Blaker, Robert Ackerson, Richard Bodle.

One of the northern wings contained wards for males not capable of hard work, sleeping rooms, an eating room, sick rooms, and a boys' school. Each room measured fifty feet by twenty-five feet. Opposite, were apartments for females, including the sick, those lying-in following childbirth, children, and any females not capable of hard work

The southern wings contained further sleeping rooms, a school room, and another eating room. In the yard were a corn mill, a whiting manufactory, and workshops for dressing flax and carding wool. The inmates' duties included grinding their own flour and making their own clothes, as well as toiling in the workhouse workshops where they made such items as 'whitening' (ground chalk used for white-washing, etc.) ropes, cords, doormats, rugs, and sacking.

The central section housed the entrance hall and administrative area which included a committee-room for examination of applicants, the overseers and clerk's office, and the governor's room which also had its own sleeping apartment. Behind that was a high ceilinged kitchen, wash house, brew house, bake house and a laundry. In addition, there were other apartments for males able to work, the upper floor being sleeping rooms, while the lower floor contained additional workrooms, a school room (probably for girls and infants) and a further eating room. A separate infirmary building had been added to the site by 1850.

On 12th September, 1822, twenty-seven inmates were transferred to the new workhouse from the old Market Street building, followed by a further seventy-three over the following two weeks. They were joined there by Mr Baldey, the parish surgeon, the new matron Mrs Harriett Dennet, and Mr. Hayward, the former governor of the old poorhouse. The latter remained only a few days and then inexplicably left the post. His successor, Mr Nuttall hardly lasted any longer, for after remaining for only about 5 weeks for some reason he was dismissed by the Guardians. His replacement was Mr Samuel Thorncroft, who had held a minor position in the old poorhouse.

A workhouse rule-book of 1822 included the inmates' dietary:

| Day | Breakfast | Dinner | Supper |

| Sunday | Milk Porridge | Boiled Beef or Pork | Cheese & Butter |

| Monday | Gruel | Soup of leftovers | Milk Porridge |

| Tuesday | Milk Porridge | Beef Pudding | Cheese & Butter |

| Wednesday | Gruel | Boiled Beef or Pork | Milk Porridge |

| Thursday | Milk Porridge | Soup of leftovers | Cheese & Butter |

| Friday | Gruel | Meat pudding | Milk Porridge |

| Saturday | Milk Porridge | Irish Stew | Gruel |

It was anticipated that bread and any vegetables in season would be included and adults could have a pint of beer with their dinner and another with supper when cheese was being served. Children were only allowed a half pint on both these occasions.

In 1825, changes in local administration made the workhouse the responsibility of the Vestry. The Guardians were then able to take a stronger line by making it clear that this was 'a workhouse and not a playhouse' and there would be no longer be any outdoor poor relief for anyone who refused to work. This new regime seems not to have lasted long, however. In 1834, the Poor Law Commission discovered that the fare provided at Brighton's workhouse was exceedingly generous. The 336 inmates were provided with three meals a day with no limits on quantity. Men received two pints of beer a day, children one pint, and women a pint of beer and a pint of tea. There were six meat dinners in the week and the inmates were served at table with the governor carving for the men and boys, and the matron for the women and girls. The full diet is shown below.

| BREAKFAST | Women: One pint of tea, with bread and butter. Men, boys and girls: Bread and gruel (of flour and oatmeal) excepting some old men, who are allowed a pint of tea, with bread and butter. |

| DINNER | Monday: Pease soup, herbs, &c. with bread; men and women a pint of table-beer; boys about half a pint. Tuesday: Beef and mutton puddings, with vegetables; the beer, &c., same as Monday. Wednesday: Boiled beef and mutton (sometimes pork with it), hard puddings, bread, vegetables, &c.; beer same as before. Thursday: Mutton and beef-suet puddings; beer same as before. Friday: Beef and mutton puddings, with vegetables; beer same as before. Saturday: Irish stew-meat, potatoes, herbs, &c.; beer same as before. Sunday: Boiled beef and mutton (sometimes pork with it), hard puddings, bread; vegetables, &c.; beer same as before. |

| SUPPER | Women: One pint of tea, with bread and butter or cheese. Men and boys: Bread and butter or cheese; men, one pint of beer or tea each; boys, about half a pint. Girls and small children: Bread and butter; drink, milk and water. |

After 1834

Brighton's local Act status made it largely immune from the provisions of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act and its operation as a local Act parish continued until 1930.

In October 1834, Mr Collington became the workhouse Governor holding the position until the summer of 1836. Mr Bartlett then became the next workhouse Governor at an annual salary of £160 a year. He had previously been a superintendent of pauper labour

In 1837, there was local outrage when the one of the workhouse died from a heart attack after being made to pull a cart of building shingle through the town and up to the workhouse on top of Church Hill. Local historian JA Erridge, writing in 1862, claimed that whilst poor paupers struggled to do hard physical work for a token relief payment from the parish, it was his belief that the workhouse Guardians had begun misappropriating substantial sums provided by the town rate payer. His town history records (truthfully or otherwise) that the Guardians had erected a summer house within the workhouse grounds which they used solely for drinking, dining and smoking. He suggested that to dispel any unfavourable criticism, the Guardians then moved their board meetings to a Pavilion property in Church Street, and there in private, often feasted at the parish's expense. He stated that the Guardians showed no respect for public funds and ordered new dishes and covers, pie plates, jugs, sauce tureens, cut glass decanters & stands, rummers, and knives and forks, because in their opinion the workhouse crockery was too inferior for their own use. Erridge also claimed that whilst in the board room the Guardians were served by waiters and their menu often included John Dorees (a fish delicacy) salmon, lobster, Norfolk Squab pie, poultry and numerous joints of meat. These feasts were said to be washed down with dozens of bottles of red and white wine, gallons of spirits, and afterwards boxes of cigars and copious quantities of snuff were supplied. On one occasion, even a presentation box was made available to put the snuff in. Such was the abuse of the system, wrote Erridge, that Mr. Hewitt, a Guardian of some standing, often had the audacity to send his boots to the workhouse to be cleaned and polished and then returned by a messenger to his house and another Guardian named Stoner even saw fit to place his dog in the workhouse because he found it inconvenient to keep at home.

In April, 1839, Sophia Clifton aged 17, and Olive King aged 16 charged in the local courts with the theft of a Brighton Workhouse uniform (the clothing they were wearing after absconding), and, the attempted theft of alternative clothing valued at 7/-. Having been found guilty on both counts, the two were transported to Australia for 14 years for this "wicked" crime. At this time, it is said that young females who were deemed to be "less sullied" by the male workhouse inmates, to be sent to the colonies for long periods in the hope that they would remain and become brides for convict labour who had completed their sentences. In Sophia's case, she was married within 6 months of arriving in New South Wales.

In June, 1848, Mr and Mrs Bartlett resigned as Master and Matron and were succeeded by a Mr and Mrs Cuzens. In 1849, Mr Cuzens went absent from his post as Governor, so both he and the matron (his wife) were discharged. They were replaced by a Mr and Mrs Hodges, who remained in the post for a year. In September, 1850, Mr and Mrs C J King became the new Governor and Matron, but they resigned in October 1854. A Mr and Mrs Passmore then took over the duties of Governor and Matron.

In 1853, power passed from the Guardians to the Town Council when Brighton became incorporated by act of Parliament. A decision was subsequently made to dispose of the existing workhouse and its grounds in favour of another new building, together with an industrial school for juveniles, both of which were to be built further out of town on Brighton's Race Hill. The land there was purchased at £325 per acre and later a further 20 acres of land for an industrial school at Warren Farm was acquired at £100 an acre. Plans were drawn up for a replacement workhouse. However, a major problem prevented the start of building work. The Guardians were reluctant to pay for piped water from the local pumping station to supply the new workhouse and the industrial school, so workhouse labour was used to dig a new well at the Warren Farm site. Progress was slow and the lack of water resulted in a long postponement of the building work on the new workhouse.

In June, 1859, finding that Passmore had absconded, the Commissioners discharged him and his wife. Later that month, a letter signed 'A Ratepayer', published in The Brighton Herald complained about the loss of four workhouse Governors in recent years, describing two as insolvent tradesmen and two as unsuccessful schoolmasters, one of whom was said to have run away even after having had his salary raised from £80 to £90 per annum. The writer therefore questioned the Guardians' ability and judgment to ever select an acceptable candidate. The vacancies for workhouse Governor and Matron were filled by the former clerk and assistant matron, Edward and Emma Sattin. This same couple went on to become the Governor and Matron of the new Brighton Workhouse in Elm Grove and in 1891 a plaque was erected to acknowledge that Edward had spent 32 years there as the Workhouse Master.

In 1862, there was still no progress in the construction of the new workhouse at Race Hill, since the construction of it and the 'youth wing' at Warren Farm were still reliant on a free supply of water being found. On Sunday 16th March, 1862, after four years of digging by workhouse inmates, down to a world record depth of 1285 feet, water was finally reached. Church bells were rung and there were great celebrations locally, but it was the engineers that were honoured with a parade, medals, and a banquet, not the pauper labour force. One man is said to have died during the digging work and his wife was given six pounds.

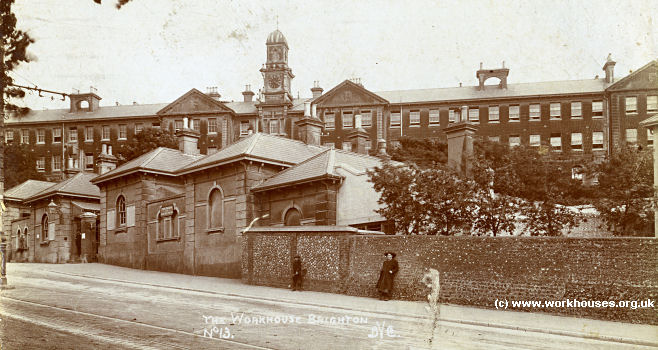

Elm Grove Workhouse

The foundation stone at the new workhouse on Race Hill at Elm Grove in Brighton was finally laid on 11th April, 1865. Two and a half years later, on 12th September 1867, the building was finished at a cost of £41,000. Soon afterwards, all the inmates were transferred from the Church Hill workhouse, with the old building was demolished soon afterwards. The vacant site was then sold off for the construction of prestige housing. The sale of the land and materials raised £42,000, providing the Guardians with an overall profit of £1,000 on their transfer from one workhouse site to another.

The new workhouse was designed by the London firm of JC & G Lansdown of Charing Cross, in conjunction with local man George Maynard. The site location and layout is shown on the OS map of 1897:

Brighton workhouse site, 1897

The impressive main block at the north of the site, was T-shaped in plan. Its frontage was four storeys with a central clock tower. The building was divided into separate sections for male and female inmates by means of iron gates in the corridors. The building employed a system of artificial ventilation.

Brighton main block from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The projecting wing at the centre of the main block included a large chapel.

Brighton rear of main block and chapel from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

An infirmary was located the south-west of the site, with a lunatics' block to its east.

Brighton workhouse infirmary block from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Brighton workhouse lunatics' block from the north-west, c.1916.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Brighton workhouse lunatics' block from the north-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Other blocks included casual wards, and foul and fever wards at the north-east of the workhouse. In 1880, three acres of land was purchased to the west of the workhouse on which new casual wards were erected in 1885, followed by infirmary pavilions at the south-west.

Brighton from the north-west with casual wards in foreground, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Brighton from the north-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 250 Elm Grove, Brighton.

By 1910, the workhouse had a scheme of classification, under which some thirty or so of the best conducted male inmates were housed themselves in more comfortable quarters. Each of the men was also allotted a small plot of ground outside, in which they could garden and grow flowers for which prizes are given during the season.

In 1914, the workhouse became known as Brighton Poor Law Institution. Between 1915 and 1920 it was taken over by the War Office and operated as the Kitchener Indian Hospital accommodating sick and wounded Indian soldiers. In 1921, it reverted to use as a workhouse until 1930 when it became Brighton Municipal Hospital. In 1948, it became part of the National Health Service and renamed Brighton General Hospital.

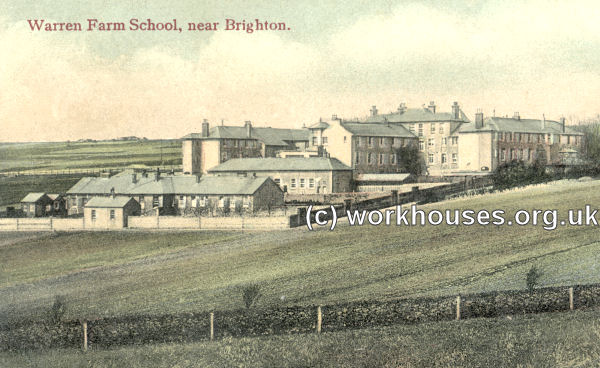

Warren Farm Schools

Warren Farm Schools for pauper children was erected in 1861-2 at Rottingdean, about two miles from the Race Hill workhouse. The establishment, whose operation depended on the completion of the well, opened on 14th August 1862 when 75 boys and 65 girls marched there in procession from the Dyke Road workhouse.

The building was broadly T-shaped in layout with boys accommodated at one side, and girls to the other. A separate infirmary was located at the south of the school, and an entrance lodge at the entrance to the site at the north-west.

Warren Farm site, c.1910.

A report in 1910 found that:

The schools are admirably placed for the purpose designed. They are upon open ground, and attached to them is a very considerable farm, from which, I understood from the superintendent of the homes, the Guardians make a profit of some £600 a year. This profit, I understand, is derived to a large extent from sale of milk, etc., and other dairy produce to the workhouse; also, of course, of vegetables, fruit and flowers. The farm buildings were large and commodious, and I saw some thirty to forty very fine shorthorn cows stalled there, and there are also a number of horses for farm work and quite a colony of pigs. I do not know the exact extent of the farm, but it must be considerable, and I was informed that the boys — or at least those of them who show any liking or desire for farm labour work — are encouraged and taught upon the farm. There was a considerable extent of ground under potatoes and other cropping.

I found the boys, that is the male pauper boys, engaged in a cricket match. Of the 300 inmates of the Homes, I think a very much larger proportion consists of boys than of girls — there being only some fifty to sixty girls. The boys who formed the cricket eleven seemed to have been well taught, and the cricket match, at which I was present for some time, was far from being devoid of interest. Generally speaking, the whole school seemed. to take an interest in the match and appeared to be very healthy and generally robust and well-cared for. At the far end of the cricket ground there is a swimming pond, which has been recently built at a cost of some £500, and on the Saturday afternoon when I was there, it was given up to the girls in the school. They had a swimming mistress giving them lessons who was paid at the rate of 7s. 6d. a lesson, I was told. It appeared to me that a swimming pond of this kind, within view of the sea and not more than a mile and a half from it, afforded considerable ground for criticism of the methods of the Guardians. At the same time, there can be no doubt that such a swimming bath must be of much practical use and service to the children, leaving out of view entirely the cost to the ratepayers.

In the school itself, over which I was taken by the superintendent, there is, as Mr. Spooner says, a very sound technical education provided. I was shown the tailoring department, where the boys are taught to make and mend their own clothes; also the boot-making department, which trade they are also taught. Further, the school was furnished with a typewriting machine; and those who have a taste for drawing and painting are encouraged to take to them. The schooling and teaching are done on the premises and the children do not attend the public schools of the district, mainly, I was told, because the schools are too far distant, although Brighton itself is only a few miles off, and of course there are ample means of communication.

The dormitories seemed to me to be most roomy and comfortable, and everything was as clean and tidy as could be wished for in every department. I saw the girls preparing their supper table, and found that their supper on that occasion was to consist — partly at any rate — of lettuce salad. provided from the garden, which garden was, as I have said, well stocked with vegetables of every kind including asparagus. The roses in the garden could not well be beaten.

One feature of this school, which I do not think I have heard of elsewhere, is that the Guardians have arranged that the children shall, as a reward to special merit — whether on the ground of good conduct or not I do not know — have pecuniary prizes given them, these being small sums of money, probably a few pence, at a time. This money is banked or retained for them against the time for their leaving school. But it seems very doubtful whether such an arrangement can be justified, and of course, whether a boy has anything to his credit or not on leaving school he must be provided with some funds when he starts to learn a trade or becomes apprenticed; and if good conduct requires to be recognised, I think such recognition should take some other form than that of a pecuniary gift.

The superintendent showed me with much pride the records of those who had left the school during his term of office. Many of them had joined the Army, some the Navy and others had entered different trades and callings. The superintendent had in his possession many letters from old boys and girls, all showing their affection for the school and the regard they had for those who had looked after them there. There can be no question whatever as to the success of the school, and as to the fact that very few of those who have been fortunate enough to be educated within its walls are ever likely to become paupers or to be found within the walls of the workhouse.

In 1989, Mr Holland, a 71-year old local resident who remembered the school, recalled that it had a high wall around it and that there used to be cut glass on the top. The school's location was then 'in the middle of nowhere' but there used to be a small shop across the road that used to sell toffee apples. The school used to compete in marathons against local boys with which the locals used to win. However, when it came to boxing matches, the Warren Farm boys would usually win.

Warren Farm School frontage from the south-east.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Warren Farm School frontage from the north-east.

Courtesy of Janice Schwefel.

Warren Farm School from the north.

© Janice Schwefel.

Warren Farm School from the east.

© Janice Schwefel.

Warren Farm School frontage from the south-east.

© Janice Schwefel.

The school had a military-style boys' band, which gave performances at local events such as the 1923 'Band of Hope' demonstration shown below:

Warren Farm School band, 1923.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Below is a photo of the Warren Farm staff from around 1930. At the centre, seated sixth from the left, is Mr Hollingdale who was Superintendent of the school from 1910-35. His wife, the Matron, is next to him.

Warren Farm School staff, c.1930.

Courtesy of Janice Schwefel.

The site later became known as Fitzherbert School. The buildings were demolished in the early 1990s.

Staff

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1881 Census - Brighton Workhouse

- 1881 Census - Warren Farm School

- Warren Farm School Placements (1891-1915) - View or Download

- Warren Farm School Admissions/Discharges (1855-90, girls only) - View or Download

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- East Sussex Record Office, The Keep, Woollards Way, Brighton, BN1 9BP. Holdings include Guardians' minutes (1902-30); Master's report books (1911-1930); Baptisms register (1915-1929); Creed register (1877-1930); Register of persons of unsound mind (1889-1930); etc.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Carder, T. (1990) The Encyclopaedia of Brighton

- Erridge, J.A. (1862) History of Brighthelmston

- Gooch, J. (1980), A History of Brighton General Hospital

- Grant R.C. Brighton Paupers (SFHG Journal, March 1991)

- Grant R.C. The Woodingdean Well (SFHG Journal, June 1994)

Links

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to:

- Roy Grant, who compiled the information on Brighton's early workhouses.

- Janice Schwefel, for very kindly contributing the pictures and information on the Warren Farm building.

- Clive Reedman of the Here In The Past Project at the Regency Town House, Brighton who carried out and supplied the Warren Farm Placement and Admission and Discharge Registers.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.