Rowton House — King's Cross

In 1892, a new type of hostel for down-and-out or low-paid working men appeared in London — the first of the Rowton Houses created by philanthropist Lord Rowton. His aim was to provide a cheap accommodation that was better and cleaner than anything else available at the time. An overview of Rowton's scheme is given on a separate page.

The first Rowton House, at Vauxhall, which opened in December 1892, was personally financed by Lord Rowton. Following its success, a limited company was formed to expand the scheme. The King's Cross Rowton House, at the corner of King's Cross Road and Calthorpe Street, was the next to be built — it opened on 1st February 1896 and provided 678 beds. The location of the site is shown on the 1916 map below.

King's Cross Rowton House site, 1916.

King's Cross Rowton House, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

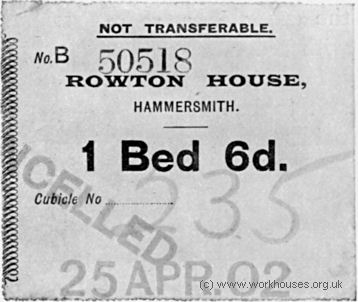

Rowton Houses were all constructed along the same basic lines. The ground floor and basement contained the entrance hallway, dining room, smoking lounge, reading room, washrooms, barber's shop, shoemaker's and tailor's rooms, clothes and boot cleaning rooms, parcels room etc. The upper floors contained large numbers of private cubicles each of which contained a bed, chair, shelf, and a chamber pot. Residence in the establishment cost 6d per day although no access to the cubicles was permitted during the daytime. Lodgers could either buy food in the dining-hall or cook their own food.

King's Cross Rowton House reading room, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

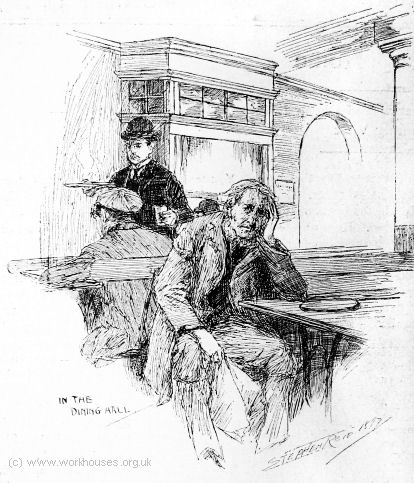

King's Cross Rowton House dining hall, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Here is a description of the King's Cross Rowton House from 1897:

Life at a Rowton House.—The Poor Man's Hotel.—

Cheerful and Cheap Lodgings Out of the Common.

It is about seven o'clock, and the toilers or unemployed, or whoever the lodgers may be, are turning in. They file past the office where a clerk takes the 6d. for a night's lodging, and gives the lodger a key. Some are permanent residents, and enter their hotel with a familiar air. A few who have supped are sitting on the garden seats thoughtfully provided for them in the lobby. To the left you enter a large smoking-room; and note the comfortable chairs and benches, solid tables, the glistening walls, and the beautiful pictures. The chairs are well occupied. Some men chat together in groups, play draughts or dominoes; others read papers; a few are industriously addressing wrappers; others, again, sit silently apart smoking, thinking out the problem of life is it presents itself to the sixpenny dosser. We pass next to the dining-room, where there is eating accommodation for nearly 400. On the way we pass the shop and a room where the crockery is stored. The shop is a universal provider so far as the lodgers are concerned. Pennyworths and half-pennyworths of everything they need may be purchased here. The quality is excellent, and the price lower than in the retail shops outside. The shop sells notepaper, stamps, and cigars from a penny upwards. There is also a restaurant, and the food is served from the bar of the shop. Everyone is his own waiter. A large bowl of soup may be had for 1d., roast beef is 4d., steak pudding 3d., cold meat 3d., potatoes 1d., tea 1d. a large cup, and a slice of bread and butter ½d. But the lodger may prefer to be his own cook as well as his own waiter. In that case he has the utensils of the establishment at his disposal, a sink with plenty of water just outside the dining-room door to clean his provisions, and cooking ranges are in the room. The lodger can buy his provisions at the shop or bring them in. He can use his own teapot and cups if he likes, although it should be noticed that the Rowton House crockery is very good quality, and lodgers are not charged for breakages. You are impressed with the scope there is for individual tastes. Communal comforts combined with individual liberty might be the motto of Rowton House. You see one man sitting down to a big spread. He has made a table-cloth of an evening paper and has bought two or three courses from the kitchen. He is dining, perhaps, at the rate of a shilling a meal. Near him is another man who has just cooked a kipper on the dining-room fire. He has a big teapot and a tin of condensed milk, as it lasts longer and is cheaper than a half-pennyworth from the shop. He has large slices of bread and butter. His dinner will not cost him more than 4d. But there is a thin, careworn man, who is sustaining life on a pennyworth of soup — good nourishing stuff it is — a half-penny worth of tea, and a halfpenny slice of bread and butter. He dines for 2d. In fact, the impecunious lodgers can live on 2½d. a day at a pinch. A big bowlful of soup with a chunk of bread costs l½d., is one meal, and for another penny he has tea and bread and butter. The men move quietly about the dining-room, or sit in ones or twos at the tables. A few have fallen off to sleep without moving. The servants of the establishment do the washing up.

Proceeding on a further tour of the ground floor we visit the reading-room, a very bright room, well lighted, and decorated with engravings of famous pictures — every room contains valuable engravings — and heads of deer shot by Lord Rowton in the Highlands. There are two bookcases at the end of the room. Most of the men are reading either books from the library or evening papers, the wrapper addressers are again represented, while some are lolling unconcernedly in the armchairs, or have gone off to sleep. Lord Rowton provides the books, and they are lent out free to lodgers. The favorite authors are Captain Marryat, Dickens, Thackeray, Lytton, Kingsley, and Charles Lever. The classics are not so much in demand. One philosopher complained that all Carlyle's works were not in the library.

In these three rooms we have seen several hundred lodgers, and a contented set of men they are. One is impressed with the quiet behavior of the men. There is no loud talk, no noise of any kind. Most of them seem to go their own way. A considerable proportion are working men, but Lord Rowton does not ask who the lodgers are. They may be men earning £3 a week, who could afford a house to themselves, or they may be poor unemployed waifs, who have difficulty in gathering in as much as will keep them alive in this cheap lodging. Some are in rough, work-a-day dress, some are out at heel, a few have the air of clerks, and top hats are not rare. Whatever they be, and however they may be dressed, it is evident that all are at home. It is also clear that they reciprocate the thoughtfulness which has given them so much comfort for a sixpence, and co-operate to keep up the reputation of the House.

In the basement floor are found men busy with their toilet. There is a large lavatory with hot and cold water always ready to be turned into 80 basins. There are troughs for feet washing, baths which cost a penny. There are dressing-rooms for those who wish to change, a barber's shop, a tailor, and a shoemaker. The accommodation for these craftsmen is provided by the company, and a moderate charge made by the men who do the work. The lodgers' washhouse was an interesting feature. The men can do their own laundry work. There is every facility, but a laundryman finds employment in working for the lodgers. There is a heating stove for speedy drying, and a rare assortment of linen and garments were hung up to dry or tied up in small parcels. The lockers are in the basement. Every lodger has a locker and a key to himself. There is also a parcel-room where lodgers can leave things too bulky for the lockers. Its contents just now include an up-to-date bicycle with pneumatic tyre.

The sanitary arrangements of the House are excellent, and so well are all the rooms ventilated that they are not in the least "smelly." Between seven and eight o'clock the men begin to go to bed. They are let upstairs in batches every quarter of an hour. Each one has a cubicle, which is a little room with a comfortable bed and plenty of blankets. There is a window to each cubicle, which explains the multiplicity of the small apertures: As there are 577 cubicles, the windows, adding those of other rooms, must be considerably over 800. Although the casual visitor is struck by the quiet, orderly demeanor of the men and their contentment, that does not mean that discipline is not maintained. On the contrary, there are rules which must be strictly observed. Mr. Hyatt, who is at the head of this establishment, carries out the regulations for its good government to the letter. The great point is cleanliness. The men must be clean, or they do not stay at Rowton House. Almost every day one or more are reported, and the attendant on night duty captures the offenders as they go to bed. For the first offence a caution is given, but the offender has to reform at once or leave. We may say, however, that the men co-operate in maintaining good order. It is a striking compliment for them, and at the same time to the civilising influences of Rowton House, that neither at this House nor at its predecessor in Vauxhall has there ever been any case of a lodger defacing a table, marking a wall, destroying anything, or writing any indecent expression any where about the buildings. The men appreciate the way in which Lord Rowton and his colleague, Sir Richard Farrant, have so carefully considered their comforts. Lord Rowton himself engenders the spirit of good fellowship among the men and co-operation between them and his company. He discourages any "my lording" of him, as he jocularly remarks, and is familiarly addressed as the "Guv'ner." He makes it clear to the men that, while he looks after them, his company are not philanthropists. They are supplying a great public need, and earn a dividend; but, on the other hand, give the best possible return for 6d. a night which they can. Further, they are always anxious to accept suggestions for improvement, although there is little room for that. The new Rowton House, now almost complete at Kennington, is larger than the King's-cross-road one, and will, if anything, be better, although, from a structural point of view, there is hardly any room for improvement.

Many notable people have visited this King's-cross-road House, and have been struck with the success of the enterprise. The visitors include the Duchess of York and the Duchess of Teck, Lord Llandaff, the Duke of Portland, Lord Balcarres, Lady Tweedmouth, Dr. Collins, chairman of the L.C.C., Sir Squire Bancroft, Mr. Moberly Bell, manager of the Times, Mr. Rennell Rudd, poet and diplomatist, Mr. Whitelaw Reid, formerly American Minister in Paris, Mr. Jas. Knowles, editor of the Nineteenth Century, Mr.- Sydney Grundy, Mr. Fred Terry, Miss Marion Terry, Sir Edward Bradford, the Commissioner of Police, and Mr. Stuart Wortley.

A resident of the King's Cross House in 1899 also described its facilities:

These gates are closed at nine-thirty in the morning, and kept, locked all day until seven-fifteen, when one of them is opened to admit the first batch of sleepers, mostly men who have to rise at three, four, or five in the morning—workers in the Smithfield Meat Market, sellers of newspapers, and workers among the vegetables in Covent Garden.

This gate is opened again every quarter of an hour, when a fresh batch of sleepers will have gathered at the gateway, where they have to show their cubicle ticket, which is marked by the attendant, or stamped 'cancelled' if their time has expired.

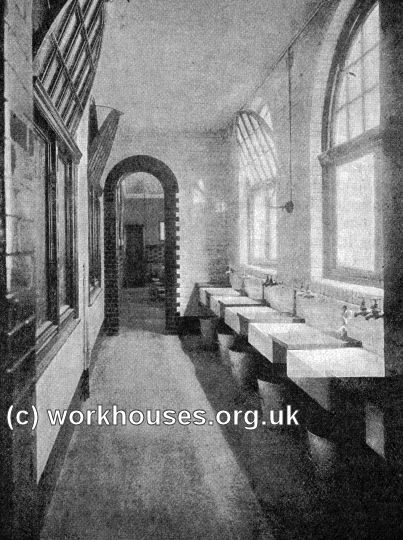

There are no appliances for washing on the cubicle floors. Washing is done on the ground floor. There are eighty wash-hand basins, with hot and cold water, towels hung upon rollers, and you supply your own soap.

There is a long; narrow room containing twelve large foot-baths in which the men may wash their feet.

And last—if it ever should be that the people for whom Lord Rowton has built these homes should wish to raise a tribute to his memory, let them carve at the base of its granite column that he gave them a bath, a clean towel, and soap for a penny.

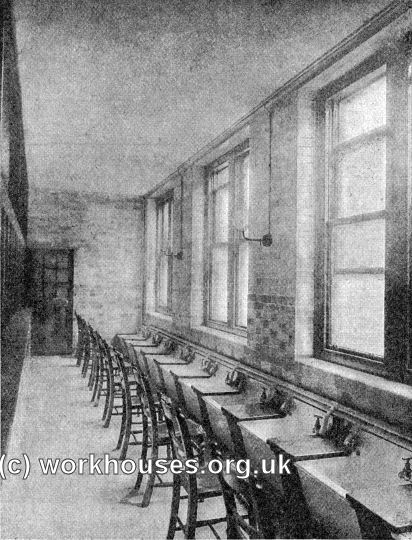

And now we will pass to the breakfast and dining rooms. There are two rooms. The larger room contains thirty-eight tables made of oak, the smaller room nine tables—forty-seven tables in all. Four people can dine with comfort at each table, giving accommodation for one hundred and eighty-eight people at a time.

In the larger room there is a bar for the sale of provisions. At this bar there are three things they sell for a farthing—milk, matches, and vinegar. I bought a farthing's-worth of milk to use at breakfast this morning. For a halfpenny you can get a cup of tea, coffee, or cocoa, bread, watercress, onions in spring, marmalade, pickles, and butter. The articles to be purchased for a penny are too numerous to mention, but to-day you may get a small plate of cold meat, potatoes, and a salad of either cucumber or lettuce with tomatoes, the cost of which will be threepence. The working man dearly loves a salad. The walls of this room are hung with familiar engravings—Landseer's 'Horse-Shoeing', 'Elaine' ('the lily maid of Astolat'). In the smaller room the walls are brightened with chromolithographs—prominent among them Millais' 'Bubbles'.

There are two sitting-rooms, and in one of them a library, to which have recently been added two hundred and sixty new books, well printed and excellently selected. So far as my observation goes, Dumas seems to be most popular. I asked a workman the reason of this, and he answered: Because there's plenty of "go" about him.' Captain Marryat comes next—Midshipman Easy and delightful Peter Simple. Who would not be a boy again to read Peter Simple? But in this library there is one omission. Among these six hundred fellow-lodgers of mine, there are at times sorrowful people for whom there should have been provided a copy of Robinson Crusoe. You may play at draughts or chess, but cards are not permitted.

King's Cross Rowton main entrance, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton lodgers' footbaths, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton cafeteria, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

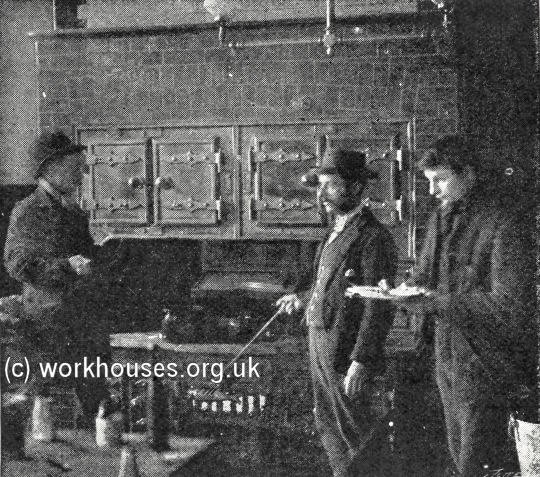

King's Cross Rowton residents' kitchen, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton lodgers' scullery, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton dining room, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton smoking lounge, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

King's Cross Rowton reading room, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

On 8th December 1906, a new wing was opened increasing the house's capacity to 964 beds.

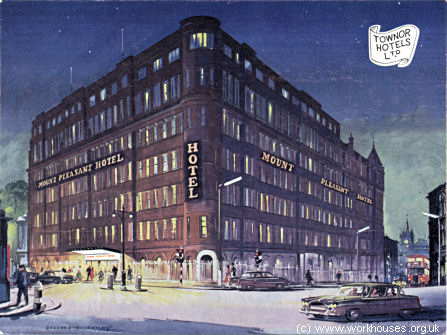

The King's Cross Rowton House continued in operation until 1960, by which time prices had risen to 3s.6d per night for a simple cubicle, to 4s.6d - 7s. per night for more comfortable bedrooms. Over its life it had provided over 20 million bookings. After a £300,000 refit, it re-opened on October 9th 1961 as the Mount Pleasant Hotel with 340 single and 82 double rooms, each equipped with a radio and telephone. A single room with bed and breakfast now cost 21s, or 35s. for full board. In 1967, the owners successfully sued the author, publisher and printers of Len Deighton's London Dossier which claimed that the hotel was "too expensive for place that used to be a hostel for down-and-outs". The book also described the remaining Rowton Houses as "grim places, echoing with the cries and coughs of defeated men."

A publicity shot of the former King's Cross Rowton House after its conversion to a hotel, c.1961.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Mount Pleasant Hotel, King's Cross, 1960s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Other Rowton Houses

The other Rowton Houses in London were:

- Vauxhall — opened 31st December 1892

- Newington Butts — opened 3rd December 1897

- Hammersmith — opened 2nd December 1899

- Whitechapel — opened 11th August 1902

- Camden Town — opened 7th December 1905

A number of Rowton-style hostels were also opened outside London, such as the Birmingham Rowton House in 1903.

Bibliography

- Cornes, James (1905) Modern Housing in Town & Country (London: Batsford)

- Deighton, Len (1967) Len Deighton's London Dossier (London: Cape)

- Farrant, Richard (1904) Lord Rowton and Rowton Houses in Cornhill Magazine, June 1904.

- Sheridan, Michael (1956) Rowton Houses 1892-1954 (London: Rowton Houses Ltd)

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.