Charles Burgess

Charles Burgess, aged 9. |

Charles Daniel Burgess was born on October 22nd, 1911, in the back streets of London's Bethnal Green. He was the first of three further children of the marriage between Richard Burgess, a widower with four sons and one daughter, and Mary, a widow with one daughter, Jinny. The older boys all saw action during the First World War but came through unscathed. One of five-year-old Charles' own wartime memories was of a massive explosion on 19th January 1917 when 50 tons of TNT blew up in a docklands munitions factory. The noise of the blast could be heard as far away as Southampton and Norwich. More than 70,000 buildings were damaged and 73 people were killed. It was claimed by the Authorities to be the work of German agents. By the end of the war, the family had moved to a six-room house in Mansfield Street, later called Whiston Road. However, in 1919, an event took place which devastated the family, as recorded below in Charles' own words... |

My Father worked as a stoker in the local Gasworks in Whiston Street. His job involved feeding coal into a series of ovens. The coal was then baked, not burnt, and when all the gas was extracted the gas was fed into immense cylinders called gasometers. The dead coal was then raked from the ovens and taken away by a moving belt, and then it was cooled by water where it became coke and used as a fuel. One Friday night in 1919, on night-shift, when he was raking the dead coal from the ovens with a long handled rake, the rake got stuck on something inside the oven. He gave the rake a strong tug; the rake suddenly came loose and struck him in the stomach. It didn't penetrate the skin, but ruptured his internal organs. He was brought home in great pain.

On Saturday morning Mother called in a doctor who ordered him to hospital immediately. He died at 11 o'clock on Sunday night. Dad had lots of relatives, and when he was buried there were many carriages—horse drawn in those days. It was the done thing then, to have the coffin at home a couple of days before the funeral took place and have it laying open in the parlour for visitors to see the deceased. My Mother wanted me to kiss Dad, but I was a bit scared. On the day of the funeral the lid was screwed shut and he was buried at Manor Park Cemetery where most East Enders buried their dead. Dad was a big shot in the factory Union, and when the cortège left the neighbourhood, walking, as they did in those days, the Union had two men marching in front with the Union banner. The cortège had to go pass the factory gates on the way to the cemetery. It stopped for five minutes when it reach the gates so that the men who were working that day could remove their hats in respect and silently stand in honour of him. Mum told me later on in life that the Union wanted to have the Union brass band marching in front too, but Mum thought that was a bit too much.

There was no widows' pension on Social Security in those days, so Mum had to approach the Board of Guardians attached to the Local Council, otherwise known as Poor Law Relief, also nicknamed 'The Bun House'. Mum was given vouchers that had to be changed at the local butcher shop for meat. She was also issued with vouchers for bread coal and dairy products. The rent was paid and she was also given money for clothes and vegetables etc. She was told that the three oldest children would have to go into a children's home, meaning Mary and Tom and me. Tom contracted ringworm—a skin complaint, and was allowed to stay at home. He had to have all his golden ringlets shaved off so that the ringworm could be treated. Before going, we spent the weekend in the local workhouse at Shoreditch.

Shoreditch workhouse, 2001.

The children's home was called The Hornchurch Cottage Homes for Children, and financed by the Shoreditch Borough Council and Bethnal Green. It was situated between Romford and Hornchurch in Essex. It was then all just farms and meadows. The home was in a country lane and was entered via large gates with a lodge house at the side for visitors. You entered a long drive and the first house was where the superintendent lived, further along were six cottages, each named after a famous woman. There were three each side, each housing approximately 35 girls.

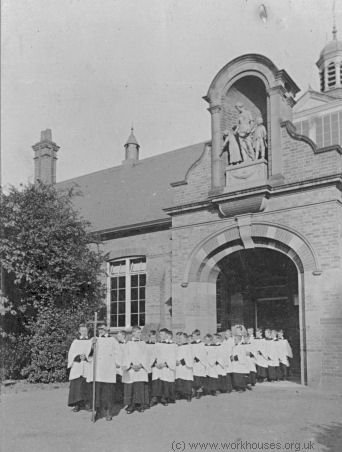

Hornchurch Cottage Homes, c.1910

Then on the left were the school (which doubled as the chapel on Sundays), the swimming baths (rarely used) the gymnasium, and the drill hall. Opposite the school stood the Administration buildings. These consisted of the dairy, the bakery, a tailor shop and a boot-repair shop. There was also a shop for the maintenance of the cottages, and a place for the resident gardener. Fresh milk was delivered daily from one of the nearby farms, and one of my first jobs was to collect a two-gallon churn of milk each day for my cottage. Next there were six more cottages named after famous men (mine was to be 'Landseer'). Again, there were three each side and each was capable of housing 35 boys. Each cottage had a large entrance hall, a kitchen with a huge double oven fire grate and a dining room. There was a day room for reading, playing chess, draughts, and children's card games. There was a plot of land at the rear with a few apple and pear trees, redcurrant and blackcurrant bushes, and a small playground. On the first floor of each cottage, were three dormitories and the washroom. Each dormitory held twelve beds, and the washroom contained three bathrooms. There was also a bedroom with its own bathroom for our foster parents (who we had to call 'Mother' and 'Father'). Our foster parents also had their own sitting room on the ground floor. Each boy had a towel and soap, and a drawstring bag containing a brush and comb. All belongings were marked with a personal number—all his clothing, slippers, and nightshirt, even his best Sunday suit. My number was two. Our weekday clothes consisted of short trousers, a shirt (cotton for the summer and flannelette for winter), a jersey, black stockings and boots. We all shared boot-cleaning brushes and blacking. All boys up to sixteen years old wore shorts. Our Sunday-best suits were made from Yorkshire tweed and consisted of a single breasted jacket, and trousers. The jacket was buttoned to the neck and collarless. A separate stiff white cotton collar and a clip-on bow tie were worn outside, on top of the jacket neckline. The jacket had two breast pockets and two side pockets, all with buttoned flaps, and a buckled belt, which was sewn to the jacket at the back but left loose at the front. The trousers were... wait for it... breeches! They were cuffed just below the knee and fastened with two buttons on each cuff. Together with black stockings and boots, we must have looked a real treat. I still don't remember how we kept those stockings up, but I do remember that the first thing I learned was to darn the holes when they appeared... and darn them properly too!

Classes were held in a very large hall in the schoolhouse. The wooden desks and fixed benches were in two rows of about twenty desks with an aisle down the centre and an aisle on either side. Each desk had a hinged lid with a space beneath to keep belongings in. The backrest of the bench was hinged so that it could lean forward towards the desk. Unlike the two-seater desks that I was used to in London, these desks each seated six boys.

In the first two or three rows in each line of desks sat the youngest boys, the next two or three rows were taken by older boys and so on with the oldest boys at the back. There were only two teachers, both male, who gave lessons to each boy suitable for his age group. The boys attended school in the mornings, and the girls attended school in the afternoons. On Sundays, the girls and boys attended Service together, with the boys on one side and the girls on the other. That was the nearest we got together, the girls and boys looking at each other out of the corners of their eyes. After Service, the girls were led out first and after a short period, the boys followed. The same hall was used for Sunday Chapel. The backrests were pushed towards the desks so that we sat facing the back of the hall, and towards a shutter which, when rolled up, revealed the Altar and the bible stand.

Hornchurch Cottage Homes, c.1910

When I took my first bath, there were about five other boys of about my age and we bathed two to a bath and were all washed by our foster mother. I was so embarrassed. Well, it's not like being washed by your own Mum is it? There were no lavatories in the cottages. They were outside, at the back, and were known as 'the dykes'. If you wanted to go during the night, there were chamber pots outside each dormitory, three to each dorm and had to be emptied each morning by the eldest boys. There was also a laundry at the back of the cottage, and several boys were detailed each week to do all the washing and ironing (including ironing the stockings). The washing was done in a wooden tub and a 'dolly'. A dolly is like a 10-inch three-legged wooden stool on the end of a long handle, which has a crosspiece grip at the top. The tub was filled with boiling water with some sort of washing powder added (probably soda), then the dirty clothes added. The dolly was put in the water—legs first, and holding the crosspiece grip, it was rotated to agitate the contents of the washtub until deemed clean. Thirty pairs of stockings at a time were washed this way.

The first thing I was taught was how to make my own bed, and make it properly according to the rules. Another job I had was cleaning the cutlery. Spoons and forks were cleaned with a cloth and white paste and then polished. Knives were cleaned in a knife-cleaning machine. I also had to polish the brass knob on the front door and the backplate of the bell-push, which was about six inches in diameter. But the longest and the worst job I had was peeling enough potatoes for 36 boys every single day.

Our breakfast every day was a plate of porridge cooked the Scottish way; with water not milk, salt not sugar. It wasn't compulsory to have it if you didn't want it. It was so thick, you could turn the plate upside down and the porridge would stay on the plate! We also had two slices of bread and margarine, which was known as 'two dorks', and a mug of cocoa. I didn't see a cup of tea for about three years. We had a hot midday meal every day. Sometimes it was stew, or 'sausage toad', or roast meat with boiled potatoes and cabbage. On Saturday we would have mashed potatoes cabbage and corned beef. But on Sundays we always had a roast dinner; roast beef with roast potatoes and all the trimmings. We always had a pudding; sometimes rice or tapioca, or boiled suet pudding with golden syrup, or 'roly-poly pudding' with currants. On Saturday we had jam tart and on Sunday we always had 'jam roll'. For our tea on weekdays, we would have the same two 'dorks' and cocoa, but on Sundays we also had a piece of cake. Every two or three months the Homes Committee from London would visit. Then, in the middle of the week, we would get a roast dinner!

There was nothing Dickensian about the home. I never once saw corporal punishment. They had other ways of punishing naughty children. One way was to make you stand under the clock that hung on the wall out in the entrance hall. You stood there nearly all day facing the wall, but this was a rare punishment. There were no 10ft high walls or iron fences surrounding the buildings, in fact, only a four or five-foot hedge bound the playing fields where the football pitch and the cricket field were. In the five or six years I was there, I think no more than a couple of boys ran away. They were all brought back, and anyway, most of the boys had nowhere to run to. These runaways were the only ones punished with six strokes of the birch and 'sent to Coventry' to one of the cottages that were empty.

I can't say that I was unhappy there—I had a clean bed to sleep in (in it at 8 o'clock and up at 6 to the sound of a bugle played by one of the band boys). We had our own military band. I tried to get into the band to play the clarinet. I was learning to run up and down the scale by music score for about two months, I then had to have a medical and was told I didn't have enough wind. I was a bit choked at this news. We had a good band, with the boys ranging from seven to sixteen years in age. We were not allowed to mix with the girls except at Sunday Chapel, and even then we were at a distance from them. The Superintendent conducted the service, and also played the organ, which was pumped by one of the older boys. Further down the drive from the cottages was a small infirmary, further on there were two cottages for tiny tots—boys and girls. Even they were kept separated. That's where my sister Mary was. I rarely saw her. She didn't go to chapel.

My Mother wasn't able to visit us very often. She probably couldn't afford it. I suppose when she did visit, that was the only time I was able to see and talk to my sister Mary.

Every six months, a dentist would call to examine our teeth. Each cottage was visited separately. Although there was a dentist's chair in the surgery, it wasn't used. We just stood in front of him, were told to open our mouth as wide as possible while he poked the fingers of his left hand around our mouth and teeth. He always held his right hand firmly behind his back. If he found a bad tooth, before you could close your eyes, his right hand was there with the pliers and your tooth was in the tray... no gas and no cocaine! He wore knee-high leather gaiters and it was rumoured that he only wore them because he was kicked so often!

Once a year, in the summer, we had Sports Day, and quite a lot of the boys had visitors. The Homes Committee also attended. Each cottage competed against all the others. There was running, high and long jump, obstacle races, and tug-of-war. There was a prize of a shield for the tug-of-war contest, and only two cottages competed for it —'Landseer' (my cottage) and 'Nelson'. I was always in the 'tug' and we won the shield almost every year. The shield was engraved with the winning cottage's name and held for a year. After the field sports finished, everyone went into the swimming pool house, where swimming races and diving were held. After the competitions were finished, all the competitors dived into the pool. Then the visitors and staff would throw coins into the water and laugh at the antics of the boys trying to get to the bottom of the pool to retrieve them. After this jollity the visitors and staff adjourned to the Drill Hall where they were served tea and cakes. Some of the boys then put on a show with Indian clubs and dumbbell drill, and the evening finished with dancing to the boys' Military Band.

I had been in the home for about two weeks when my 'father' asked me a question. I didn't hear him properly and I said "what?" He went absolutely bananas. "Don't you ever say 'what' to me again!" he shouted "'Watt' made steam engines. In future, you must say 'I beg your pardon'". It took me a long time to get used to this habit. When I finally returned home to London, and said to the boys there, "I beg your pardon?", they all fell about laughing and mocked, saying, " Coo, 'ark at 'im, ain't 'e posh!" and started to chant, "Don't beg... sell bootlaces and matches!" I soon lost that habit!

I had been in the home for about three years, when one Sunday after Service, the Superintendent told us that all the teachers had left, and until new teachers were employed, there would be no lessons. He added that if no teachers were found who were suitable, then it was possible that we would all be going to schools in the surrounding villages. That Sunday, my education ceased until I returned to London.

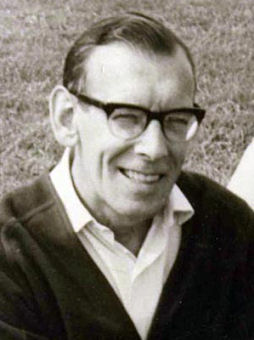

Charles Burgess in the 1950s.

Acknowledgment

- Many thanks to Delia Campbell (née Burgess) who compiled her late father's autobiography and has kindly allowed his memories of the Hornchurch Schools to be reproduced here.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.