Greenwich, Kent, London

Up to 1834

Greenwich's first parish workhouse was opened in 1724, next to St Alphege's Church. In 1725, the first edition of An Account of Several Workhouses... included a Letter from a Gentleman at Greenwich to his Friend at London, dated August 13th, 1724.

THE Parishioners, taking the same into their Consideration, thankfully accepted of this Offer, and submitted the Direction of it to such Management, as the said Gentlemen should prescribe.

MR. Matthew Marryott, of Olney in Buckinghamshire, having, with great Success, directed the setting up Houses of Maintenance for the Poor in Buckinghamshire, and other Counties, was invited to Greenwich, to propose a Plan, by which the like might be done there. Accordingly, this Summer, a commodious House has been built near the Church, at the Charge of the Honourable Gentlemen aforesaid ; and at Midsummer, all such Poor, as receiv'd Weekly Pensions from the Parish, were admitted into it, to the Number of 90 odd, and are at present employ'd in the picking of Oakum, winding Silk for Throwsters, Spinning Jersey, and such other Work as they are capable of under Mr. Marryott's Direction.

THIS Undertaking being its Infancy, it does not yet appear what will be the Success of it ; but one good Effect it has already had, viz. That those that are absolutely necessitous, are better provided for than they were before ; and many of those were before burthensome to the Parish, have exerted themselves, so as to live by their own Industry, to avoid giving that Burthen ; by which, the Parish have already sav'd considerably. And it has prov'd an effectual Means to drive Beggars out of the Town, notwithstanding the People in this House are lodg'd and dieted in so commodious a Manner as they are.

P.S. They are furnish'd with old Cable cut into Pieces, commonly called Junk, from the King's Yard at Deptford, to be pick'd into Oakum, for which they allow the Work-house 4 s. per hundred weight.

| The Bill of Fare for a Week | |||

| Breakfast. | Dinner. | Supper. | |

| Sunday | Bread and Cheese | Beef and Broth | Bread and Cheese |

| Monday | Beef Broth | Hasty Pudding | The same |

| Tuesday | Milk Porridge | Plumb Pudding | The same |

| Wednesday | Milk Porridge | Beef and Broth | The same |

| Thursday | Beef Broth | Rice Milk | The same |

| Friday | Milk Porridge | Beef and Broth | The same |

| Saturday | Beef Broth | Hasty Pudding | The same |

In 1732, an updated second edition of An Account... included An Abstract of the Rules for Managing the Workhouse at Greenwich:

THAT the Master shall keep a Book, and Register the Names of all the Poor that are maintained in the House, and that no Monies be brought to an Account but for such as are so Registered ; and that a daily Account of the Expence of Provisions be brought to a Weekly, and then to a Monthly Account, to be perused in the Vestry.

THAT all Cloaths and Apparel, Provisions, etc. that shall be furnished for the Use of the Poor, shall be view'd by the Churchwardens and Overseers, and by the Gentlemen of the Committee, or any three of them that shall be appointed to inspect the Affairs of the House, and that no Repairs be done to the said House, but what is actually approved of by the Committee.

THAT no Money be allowed by the Overseers to be paid to any Person, but by Order of his Majesty's Justices of the Peace, and the Gentlemen of the Committee then sitting, on a Day appointed Weekly for the Relief of the Poor.

THAT no Person be admitted into the House, but on the Committee-day, except on some extraordinary Occasion.

THAT a Vestry be holden in the Parish-Church the first Sunday in the Month, by the Gentlemen aforesaid, and as many of the Parishioners as please to attend, to inspect the Overseers Accounts for the Month past ; and likewise examine the Houshold Expence of Provisions received by the Master, and that a Voucher do appear for each Article then delivered.

THAT there be a Minute-Book kept, to enter all such Matters as shall happen in and out of the House, in order to be laid before the Committee at the next Meeting.

THAT there be kept four Books (viz.) A Day-Book, a Weekly-Book, and a Monthly-Book, to enter Provisions received in the House, and a Book to enter all Tradesmen's Bills, and Extraordinaries paid by the Overseers, to be brought to Account Monthly.

THAT such Orders be set up in the House as shall be appointed by his Majesty's Justices of the Peace, the Gentlemen of the Committee, Church-Wardens, and Overseers of the Poor, for the better Regulation of the House.

THE Weekly Bill of Fare for this House is much the same as in other Places.

THE House Expences for one Week, when 90 were in Family, was as follows.

| l. s. d. | |

| 48 Half-Peck Loaves at 7 d. | 01 08 00 |

| 8 Pecks of Flour at 6 d. | 00 04 00 |

| 49 Quarts of Milk at 1 d. | 00 04 01 |

| 21 Stone of Beef at 19 d. per Stone | 01 13 03 |

| 4. Barrels of Beer at 5 s. | 01 00 00 |

| Several Articles of Chandlers Goods | 01 09 03 |

| 05 18 07 |

THE Monthly Book is kept in the same Method as the Weekly.

AN Apothecary attends the Sick with proper Medicines at 15l. per Annum.

A School-Mistress belonging to the House teaches the Children to read.

PRAYERS are read every Day by the Master.

The 1732 edition of the Account also recorded that a workhouse was erected in Deptford in 1726. By May 1729 there were 70 inmates in residence, including 26 children who were all "decently lodged, fed, cloathed, and taught."

In 1753, Greenwich promoted a Local Act (26 George II, c.100) to place administration of poor relief into the hands of a Board of Guardians.

The 1724 workhouse proved inadequate for the demands placed on it and in 1765 the Greenwich Guardians began renting land off Maidenstone Hill occupied by a building known as the Pest House. The site was subsequently purchased from the Crown and a new workhouse erected. A parliamentary report of 1776 records a brick-built workhouse in operation at East Greenwich for up to 350 inmates. (The parish of Greenwich is sometimes referred to as "East Greenwich" in old documents, to distinguish it from neighbouring West Greenwich — more usually known as Deptford.) The workhouse inmates were employed in spinning mop-yarn and jersey. The staff included a mistress (salary £25 5s. per annum), a superintendant of spinning yarn (£8 8s.), his assistant who also read prayers (£8 8s.), a superintendant of spinning jersey (£7), her assistant (10s.), a beadle (£25), and a collectors (£38 on average).

A workhouse was erected in Deptford in 1726 on the site of an old manor house known as Sayes Court. By May 1729, it had 70 inmates, including 26 children, all 'decently lodged, fed, cloathed, and taught.' In 1730, Deptford was divided into two parishes: St Nicholas (which included the old town) and St Paul. In 1776, the St Nicholas workhouse was reported as being 78 feet long, 36 deep, two storeys high, and containing fifteen 'apartments' which housed up to 130 inmates who picked oakum for the Deptford shipyard. The St Paul's workhouse then accommodated 125 inmates.

Sayes Court c.1900.

Sayes Court, date unknown.

In 1731, Woolwich opened a parish workhouse at Rope Yard Rails. In 1777, it housed up to a hundred inmates.

After 1834

The Greenwich Poor Law Union was formed on 18th November 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 20 in number, representing representing its 4 constituent parishes as follows (with numbers of Guardians for each): Greenwich (8); St Nicholas, Deptford (3); St Paul, Deptford (4); Woolwich (5). The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 62,009 — ranging from St Nicholas, Deptford (population 6,036) to Greenwich itself (24,553). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £22,574.

The union initially took over the old workhouses at Greenwich (used for infirm men, and married people), Woolwich (the remainder of the men) amd and St Paul, Deptford (children).

The Woolwich Road Workhouse and Vanburgh Hill Infirmary

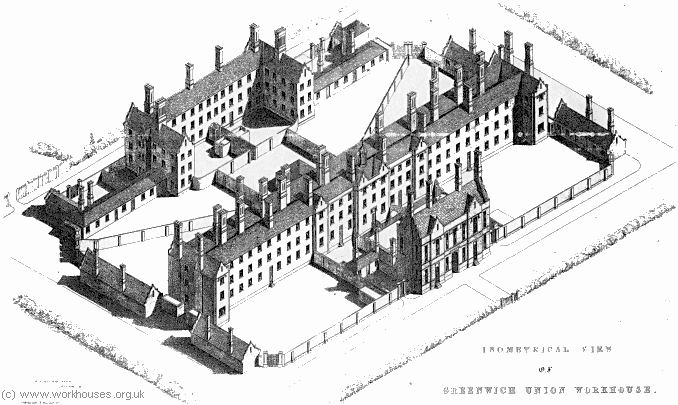

The new union workhouse was erected in 1839-40 junction of Woolwich Road and Vanbrugh Hill. The architect, RP Browne, later described his design as as 'plain but cheerful and almslike'.

Greenwich Woolwich Road workhouse from south-west, 1844.

The layout comprised a two-storey entrance block containing the board-room, porter's lodge, probationary wards, refractory wards and vagrants' wards. The three-storey main block was based on a central corridor plan. Greenwich is one of the earliest examples of this type of design which became extremely popular — around 150 corridor plan workhouses were built between 1840 and 1875. At the centre of the main block were the Master's quarters, with a T-shaped chapel/dining-hall behind. Various rooms opened off the central corridor for the various classes of inmates, including ones for 'bad women'. The upper floors contained dormitories.

Greenwich Woolwich Road part of ground-floor plan, 1844.

To the rear, at the south of the site, separated from the main block by the inmates' exercise yards, stood the infirmary block which was adjoined by wash-houses, laundry, work-rooms, and the mortuary.

A portrait of life in the workhouse and its school in the early 1860s, from a child's point of view at least, appeared in the Poor Law Board's Annual report in 1874. It was written by a former inmate, who signed himself "W.H.R.", and who later graduated to the large district school run by South Metropolitan School District of which Greenwich was part. W.H.R. — doesn't explicitly name the workhouse but it was clearly located three miles from Woolwich so was almost certainly Greenwich. Describing himself as "a ragged little urchin without shoes and cap", he recalls his arrival at the workhouse at the age of seven:

When at last I got dressed in the uniform, Mr. Willis himself marched me off to the school, and, with a full and facetious account of my bath, left me in the custody of Mr. Darley the schoolmaster. It was Saturday afternoon, and the boys were 'kept in' for previous bad behaviour. They were all standing stock still round the school, and as quiet as could be. I looked at them and wondered at seeing so many and so still. Mr. D. asked me my name. I wouldn't answer. He asked me two or three times, but no answer. At last he got off the stool at the desk, and took hold of my shoulder, and said, 'What is your name.' I was out of his reach in a moment, and shouted out as loud as I could, 'Find, out, carrots.' He had red hair. There was a titter all round the school, and one of the monitors caught me by the collar, and got a punch in the head for his pains, which did not seem to hurt him in the least. He was a big boy, and had me up to the desk in no time. Mr. D. opened the desk and brought out a cane, and told me to look at it.

Discipline at the workhouse school was certainly harsh, and even criminally brutal on occasion. W.H.R. recalls an incident involving a Mr Allen who taught the boys tailoring:

The food give to the boys was also woefully inadequate:

A separate page contains the whole of W.H.R.'s story.

One time in the year when there was some cheer for the inmates, accompanied by some good food and some entertainment, was at Christmas. Below is the scene in the workhouse dining hall at Christmas 1864.

Greenwich workhouse, Christmas, 1864.

In 1865, Greenwich was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal The Lancet investigating conditions in London workhouse infirmaries. The report on Greenwich contained a number of serious criticisms. Amongst these were:

- The low-lying site was prone to flooding and dampness.

- The water supply, partly drawn from an artesian well, was defective. Some wards had a poor supply from their taps, whilst others such as the lying-in wards had never had water laid on at all.

- The workhouse as a whole was overcrowded. At the date of the Lancet inspection, there were 906 inmates, over 100 more than the original and very improper estimate of its capacity.

- The infirmary was overcrowded, badly ventilated, and insanitary. The excreta from wet and dirty cases which soaked through the straw beds on which such patients were placed was collected in a pan underneath.

- Except for in the insane wards, there were no paid nurses although there were 198 beds in the infirmary, and over 200 other cases under medical treatment. Nursing was carried out by twenty-six pauper nurses, aged from 30 to 76, who were given allowances of tea, sugar, meat, and beer daily, and occasionally gin.

- The medical officer, Mr. Sturton, was severely overworked, with more than 400 patients and 60 midwifery cases yearly in the house. He received a salary of £200, out of which he had to pay for all drugs, except cod-liver oil and quinine.

The full text of the Lancet report is available on a separate page.

In 1868, Woolwich separated from the Greenwich Union to become a separate Poor Law Union.

In 1872, the Union (much of which formed the of the constituency of the then Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone) had a population of 100,601. Of these, 851 were inmates of the workhouse, comprising 320 males, 465 females and 66 children. The Union had also placed 357 children at the South Metropolitan District School at Sutton. A report published in the same year recorded of the Greenwich workhouse:

Mention has been made of the 400 Greenwich Union children that are at Sutton; but there are children chargeable that are too young to be sent thither, and about twenty will be found in the house.

Poor little waifs, three of them have been picked up in the streets! Who can foretell their future? They are all clean, happy, rosy, and bright-looking now, whatever their after lot may be, They are so young as not to have reached the age when dress indicates the sex of the wearer; but the mode of parting the hair and a little head ornament marks the girls.

A visit to a workhouse suggests melancholy reflections. It is humbling to note such a low form of human life, — in many instances it is more existence, not life, — an unvarying round of eating, maundering, sleeping, dozing through an existence that has ceased to have use, aim, or object. It is curious to notice the effect that the workhouse regime has in prolonging the lives of those who may have often survived hard buffetings in the world. Anxiety and care concerning the future are thrown off at the entrance to the house, and the inmates are henceforth placed under conditions more favourable to health and longevity than they have ever before experienced. In the Greenwich workhouse there are 431 inmates that are over sixty years of age.

In 1875-6, a new workhouse infirmary was erected at the south of the workhouse with its entrance on Vanbrugh Hill. The new building freed up the existing infirmary block for accommodating additional healthy inmates. A report from August 1876 described the new infirmary:

To the east and west are the female and male wings respectively, the receiving and isolated wards abutting on the corridors. The southern portions of both the male and female wings were occupied by the principal wards, each containing thirty-four beds, and measuring 106 ft. by 25 ft. The northern, together with the north-eastern and north-western, portions are devoted to special cases.

The upper floors, as far as these wings are concerned, are planned precisely as the ground-floor plan. Food and coal lifts are provided, also linen shoots. The staircases, passages, landings, and corridors are of fire-proof construction. The lavatories and water-closets are built outside the wards, and united by a necking.

Attention seems to have been paid to the subject of ventilation, for not only is the whole plan subordinate to this matter, the windows everywhere being opposite one another for the purpose of cross ventilation; but in addition to this, air-bricks, with the usual hit-and-miss gratings, are placed under every window, and air-flues are taken from the basement to the roof.

In the census year of 1881, the Union had a population of 106,000 — many of whom lived in cramped and insanitary conditions and little above starvation level. In 1885, the Union raised £14,800 from the Metropolitan Board of Works to finance a scheme to expand the workhouse and its infirmary. Two new blocks accommodating 200 chronic sick began soon afterwards. Two further ward blocks to house 250 inmates followed in 1889. The layout of the site on a map of 1894 is shown below.

Woolwich Road workhouse site, 1894.

Woolwich Road workhouse main entrance from the north, c.1954.

Vanbrugh Hill infirmary from the south, 1920s.

The Woolwich Road / Vanbrugh Hill workhouse later became St Alfege's Hospital. In the late 1960s the buildings were demolished to make way for a new Greenwich District Hospital.

Grove Park Workhouse

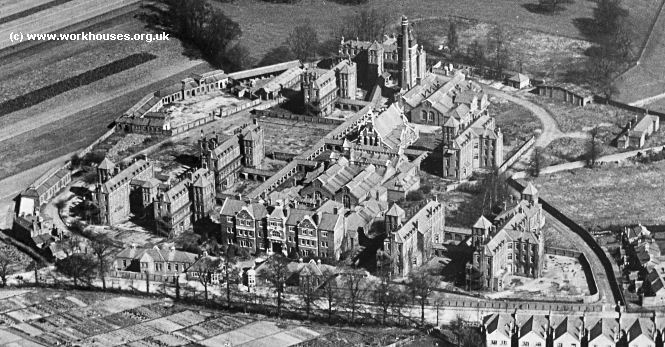

By the end of the nineteenth century Vanbrugh Hill was very overcrowded and the Greenwich Guardians instigated plans for an additional building. In 1896 they acquired a ten-acre site at Grove Park, and the following year approved plans by T & J Norman Dinwiddy for a new workhouse to accommodate 815 aged and able-bodied inmates. The foundation stone for the new building was laid on 15th June 1899, and the construction work, by T Rowbotham of Birmingham, was completed in April 1902.

Grove Park foundation stone, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Unfortunately for the Greenwich Guardians, changes in the poor-relief system had just come into operation which provided for substantially more out-relief than had previously been the case. The effect of this was to significantly reduce numbers applying to enter the workhouse. The new Greenwich workhouse stood empty for two years, during which time the press made much of the situation. The Illustrated London News described the building as being one of the most luxurious in the country with "mosaic flooring, beautiful panelling, a dining-hall fit for royalty, and a church which any rector would envy."

Grove Park workhouse lying empty in 1902.

The Greenwich Guardians applied to the Local Government Board for permission to sell off the buildings. However, the Board would only allow this if the old Greenwich workhouse was enlarged. The Guardians, presumably wishing to avoid this additional expense, changed their minds and the new workhouse admitted it first paupers in February 1904.

The location and layout of the ten-acre site are shown on the 1909 map below.

Greenwich Grove Park site, 1909.

Grove Park aerial view from the south-west, date unknown.

The new workhouse had its entrance on Marvels Lane which was flanked by single-storey receiving wards.

Grove Park entrance from the west, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham

An administration block stood at the centre of the site, with kitchens, dining-hall and stores to the rear. Behind stood a 400-seat chapel, laundry block, boiler house and water tower.

Grove Park administration block from the south-west, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham

Grove Park workhouse from the east, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Around the central buildings were arranged eight three-storey pavilions, with male accommodation at the north of the site, and female at the south. Blocks for the aged were placed at the front of the site, while those for the able-bodied were at the rear. Each pavilion housed 80-100 inmates, with one for married couples having individual bedrooms. The pavilions and central blocks were linked by covered arcades. At the north-east of the site were an isolation block and workshops.

Greenwich Grove Park from the south, 1899.

Grove Park workhouse from the east, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Grove Park aged females and married couples' quarters from the east, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Stables and a mortuary were placed along the north-western edge of the site.

Grove Park workhouse (mortuary centre) from the north-west, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1913, the workhouse started to admit epileptics from other unions. From 1914-19, the workhouse was taken over by the Army Service Corps as a barracks for training recruits.

Grove Park workhouse ("The Barracks") from the west, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After the war, the site was taken over by the Metropolitan Asylums Board but remained unused until February 1926 when it began operating as a TB hospital. In 1930, London County Council took over responsibility for Grove Park and erected a nurses' home in 1938. It remained in use as a TB and chest hospital until 1977 and subsequently became a residence for the mentally handicapped. In the early 1990s, the nurses' home was temporarily used as student accommodation by Thames Polytechnic/Greenwich University. The whole site has now been redeveloped for residential use but the entrance and administration blocks still survive.

Greenwich Children's Homes, Sidcup

Greenwich was a member of the South Metropolitan Schools District which, since 1852, had operated schools at Sutton. In 1899, the Greenwich Board of Guardians purchased 62 acres of land at Burn Oak Lane, Sidcup, on which to set up the union's own children's cottage-home village which was opened in 1902. The official foundation stone was laid on April 10th 1901 by Chairman of the Guardians, Mr John Anderson.

Greenwich cottage homes foundation stone, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The cottage homes, designed by Thomas Dinwiddy and Sons of Greenwich, comprised a total of twenty-four tudor-style blocks, set around a large green. As well as houses, the complex included a school, infirmary, swimming-baths and gymnasium, laundry and boiler house. The site layout is shown on the 1908 map below.

Greenwich cottage homes site, 1908.

Greenwich cottage homes from the west.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The site included an old mansion and stable block dating from the 1840s and known as The Hollies. The old house was retained as the administrative block for the homes, and was extended at its west end with a dining hall.

The present-day Hollies from the north, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

On 21st May, 1907, the house suffered damage in a fire.

Greenwich cottage homes fire, 1907.

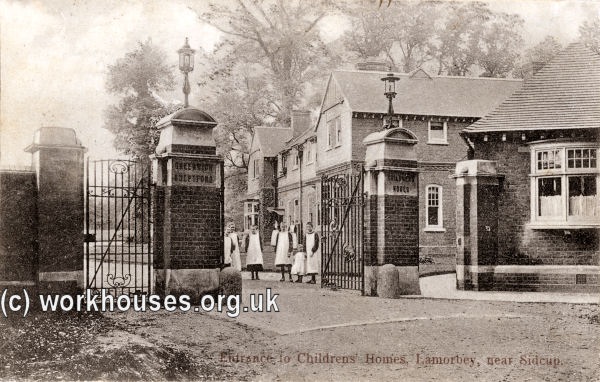

A porter's lodge and receiving block stood at the entrance to the site at the south-west.

Greenwich cottage homes entrance, c.1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenwich cottage homes lodge and receiving block, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenwich cottage homes lodge and receiving block, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Females were accommodated at the east of the site in ten pairs of two-storeyed cottages, each of which housed fifteen girls.

Greenwich cottage homes girls' houses, 1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenwich cottage homes girls' house, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Males were placed at the west of the site in four three-storey cottages, each of which could hold forty boys.

Greenwich cottage homes boys' house, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the centre of the site were two blocks. The one to the north contained a laundry and boiler house with a water storage tower.

Greenwich cottage homes laundry and boiler house, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

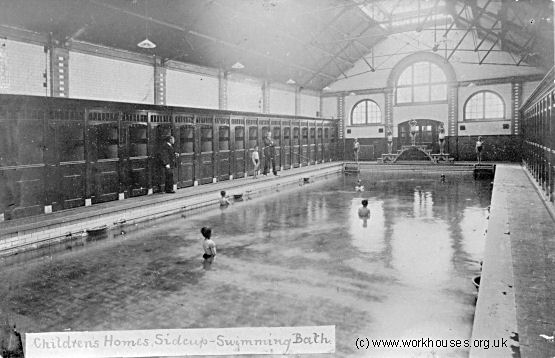

The other central block contained a gymnasium and swimming baths, the latter being still in use.

Greenwich cottage homes swimming baths interior, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Greenwich cottage homes swimming baths interior, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The infirmary was located at the end of a long drive to the north of the site.

Greenwich cottage homes infirmary from the south, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school, erected in 1903, stood amongst trees at the south of the site. It had separate entrances for boys, girls and infants, and playsheds in the yards.

Greenwich cottage homes school from the east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The staff employed in running the homes numbered over sixty as shown on the group photo below.

Greenwich cottage homes staff, date unknown.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1930, the homes were taken over by the London County Council and renamed Lamorbey School. In 1950, the site became known as The Hollies. In 1965, the London Borough of Southwark took over the establishment which then continued in use until the 1980s. In 1983, there was an outbreak of disorder following a pay dispute between staff at the homes and their council employers. Children barricaded themselves into one of the houses and police were called to forcibly remove them. Soon afterwards, the homes were closed and the site sold for redevelopment for residential use. The old Hollies mansion-house proved unsuitable for conversion and fell into decay, much to the dismay of conservationists. A compromise was eventually reached where the old house was demolished and a replica with lower ceilings built in its place.

Calvert Road Cottage Homes

From around 1901, the union operated group of cottage homes at 9-19 Calvert Road, just adjacent to the workhouse. They could accommodate 50 children. The homes may have acted as a receiving home for the Sidcup homes, and also catered for the 'ins-and-outs' — children who were in the union's care for frequent short periods.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

Holdings include: Guardians' minutes (1836-1930); Staff records (1852-1930); etc.

- Woolwich Road workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1854-1941); Births (1863-90); Deaths (1848-1941); Creed registers (1869-1938); Adoptions register (1889-1931); Lists of pauper children (1855-1937); etc.

- Vanbrugh Hill infirmary: Admissions and discharges (1876-1942); Births (1874-1941); Deaths (1892-1942); Creed register (1876-1933); Baptisms (1876-1923); etc.

- Sidcup Children's Home: Admissions and discharges (1902-39); Creed registers (1902-37); Lists of pauper children (1911-32); etc.

- Calvert Road Children's Home: Admissions and discharges (1901-28); Lists of pauper children (1901-10, 1917-28).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Coll, Gerry & Adams, Jad (2005) The Hollies - A Home for Children. IBSN 095489930X. Costs £10 + P&P from living.history@virgin.net

- Mercer, J (2002) History of the Hollises (n Bygone Kent, 23, No. 10, Oct 2002.)

Links

- Rose Lloyds memoirs which include her time at the Sidcup children's homes.

- The Lancet reports into the state of workhouse infirmaries, 1865-66

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.