Apprenticeship of Workhouse Children

An apprenticeship was an extended period of training in a craft or trade, given to a boy by an established master in the trade. Originally, boys had to be aged from 10 to 18 years old, to begin an apprenticeship, although the Parish Apprentices Act of 1698 reduced the allowable age of entry to seven. The apprenticeship normally lasted until the apprentice was 21. The operation of an apprenticeship was the subject of a legal agreement — an indenture — and usually involved the paying of a fee — the premium — to the master who would also provide the apprentice with board and lodging for the period of the apprenticeship.

Most apprentices were "trade" apprentices, sponsored by their parents, and who would hope eventually to set up in trade themselves, perhaps as "journeymen" or day labourers. However, the apprenticeship system could also be used by parishes to take poor children from the workhouse and unburden the rate-payers from supporting them, both in the short and long-term. Under the Settlement Act of 1662, an apprentice took settlement from his place of apprenticeship. It was therefore attractive for a parish to place an apprentice in a different parish which would then have responsibility should he later become a charge on the poor rate. Pauper apprentices did not usually learn highly skilled trades; instead, the boys would be taught "husbandry" and the girls "midwifery" and were effectively labourers and household servants.

Some parishes prevailed upon their own rate-payers in turn to take a pauper child for at least a year, or else face a £10 penalty. Sometimes, children were assigned by a lottery. Such impositions were often extremely unpopular, with many householders preferring to pay the fine rather having to take in a child. Where a child was reluctantly received, the result might be it being overworked and poorly treated.

A more common procedure was to offer a premium of up to £10 to anyone willing to take a pauper child in for a set period, typically seven years, and train it in a trade. This was the route famously described by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist when Oliver was offered, together with the sum of five pounds as a "porochial 'prentis". The contract was conditional, as Dickens explained, "'upon liking' — a phrase which means, in the case of a parish apprentice, that if the master find, upon a short trial, that he can get enough work out of a boy without putting too much food into him, he shall have him for a term of years, to do what he likes with."

The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act had intended to abolish the apprenticing of workhouse children, since it contradicted one of the Act's guiding principles, that of "less eligibility" i.e. that the lot of the workhouse inmate should be inferior to those outside the workhouse. Although use of the apprenticeship system continued after under the New Poor Law, it became the subject of much criticism. In the Poor Law Commissioners' second annual report, James Phillips Kay (later better known as Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth) outlined the shortcomings of the apprenticeship system in Norfolk and Suffolk:

...

the class of persons to whom the children were apprenticed were generally petty tradesmen of a low caste, who were usually unscrupulous in the neglect of their duties to the children. A parish apprentice is regarded as a defenceless child deserted by its natural protectors, and whose legal guardian, the parish, is only anxious to remove the burthen of its maintenance at the least possible cost, and with the least possible trouble.

...

After a certain interval had been allowed to elapse, means were often taken to disgust the child with his occupation, and to render his situation so irksome as to make him abscond. It will appear from the evidence which I have collected, that many children have thus been driven to ruin.

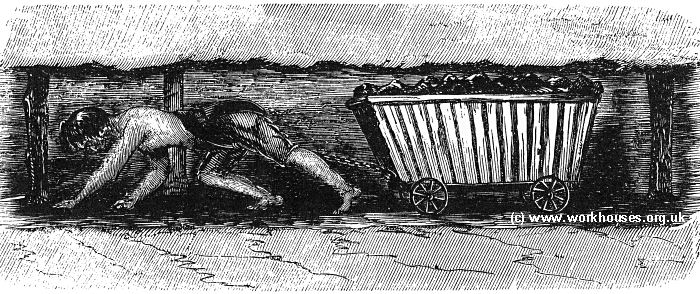

In 1842, a Royal Commission on Children's Employment in Mines and Manufactories reported that workhouse boys in South Staffordshire, some as young as eight, were being sent on "apprenticeships" of up to twelve years working in coal mines. In fact, the boys were usually employed as "hurriers" — conveying corves (large baskets) of coal from the coal face to the bottom of the pit-shaft from where it was raised to the surface.

[A "butty" was a middleman between a mine owner and its workmen, who contracted to work the mine and raise coal or ore at so much per ton.]

As a result, unions in the coal-mining areas of South Staffordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire were asked to provide detailed information on the children who had been apprenticed in the mining industry in recent years. The return from the Dewsbury Union is shown below.

| Name of Child | Age Yrs.Mos. | Apprenticeship Period. | Premium Paid. | Name of Master. | Residence. | Trade. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | ||||||

| Joseph Gaunt | 11 — | 9 years | None | David Preston | Batley | Coal miner |

| Joseph Scott | 10 — | 11 years | " | James Robertshaw | Liversedge | " |

| John Howden | 11 3 | 9 years, 9 months | " | John Fell | Batley | " |

| William Goodall | 10 — | 10 years | " | William Scaife | Thornhill | " |

| Shallam Lister | 8 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Valentine Wilkinson | ditto | " |

| Joseph Booth | 10 — | ditto | " | Richard Allatt | Denby | " |

| Thomas Townend | 5 — | went on trial and was returned in 16 days | " | William Bradshaw | Overton | " |

| Edward Robinson | 9 — | went on trial and is not yet bound apprentice | " | Jesse Speight | Flockton | " |

| 1841 | ||||||

| William Firth | 11 — | 10 years | " | John Ledyard | Mirfield | " |

| 1842 | ||||||

| George Booth | 12 — | went on trial and was returned in 3 weeks | " | Henry Chambers | Thornhill | " |

| Wiliiam Grey | 12 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Joseph Crowther | Morley | " |

| John Fothergill | 10 — | went on trial to | " | John Field | Flockton | " |

| Thomas Whindle | 10 — | went on trial and was returned in a few days | " | Henry Chambers | Thornhill | " |

Five-year-old Thomas Townend was a matter of some embarrassment for the Dewsbury Guardians as he was far too young to be bound as an apprentice. The Guardians claimed that when he had been received from a township workhouse his age had been ascertained by informal enquiry and recorded as seven years. Once the error has been discovered, he had immediately been sent back from the mine. However, Children's Employment Commission was told that the boy had only been returned to the workhouse after his grandfather and friends had threatened to report the matter to the Poor Law Commissioners.

In their return, the Burton-upon-Trent Guardians were at pains to point out the care they employed when placing children for apprenticeship: premiums in money were not allowed and the boys were instead provided with two full suits of clothes; any master applying for a boy was required to produce a certificate of character from the minister and officers of the parish in which he resides; a trial period of at least six weeks was required, at the end of which the boy was brought before the magistrates and strictly questioned as to his food, lodging, moral and religious instruction, and especially whether he had any objection to the apprenticeship being formalised.

The Children's Employment Commission's 1842 report on mines also included evidence from one workhouse apprentice, William Hollingsworth, revealing how he had had to work underground continuously for up to sixteen hours a day:

(Signed) WILLIAM HOLLINGSWORTH.

Child dragging coal in a Halifax mine, 1842.

© Peter Higginbotham.

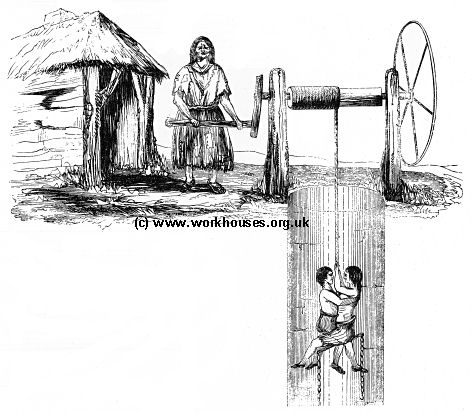

Children being winched up a mine-shaft, 1842.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Girls, too, were occasionally sent to work down mines as the Commission found in reports from Halifax:

Esther Craven says:- I have cried many a time afore now for coming into pit but I have got used to it, a think nought abou being brayed by the getters a bit.

Mary Barrett says:- I de not like working in pit, bit I am obliged to get a living. I work without stockings or shoes, or trousers; I wear nothing. but my shift.

Ruth Barrett, her sister, says:— I come down into pit in linings of old trousers, which I take off. I wear an old waistcoat and shift. I do not like working in pit; I would not do it if I could help it.

Critics of the use of apprenticeship, such as Kay-Shuttleworth, proposed that pauper children should be instead provided with "industrial training" within the poor law system, ideally in separate children's industrial schools, each serving a number of unions. Kay was particularly influenced by Mr Aubin's privately run school at Norwood which accommodated more than a thousand residential pupils largely taken from Metropolitan poor-law unions. The work of the Central Society for Education and its 1838 publication Industrial Schools for the Peasantry also stimulated interest in this approach. Although only a small number of unions initially set up such establishments, there was a gradual decline in the use of apprenticeship for pauper children. It did not disappear entirely, however — between 1834 and 1863, the Norwich Incorporation apprenticed 130 boys into twenty trades, although eighty per cent of them went into shoe-making.

The Poor Law (Apprentices) Act of 1851 improved the lot of workhouse apprentices, making their mistreatment an offence, and requiring them to receive reqular visits from their union's relieving officer.

From the 1840s onwards, an increasing number of unions began to provide some kind industrial training within their workhouses, although the resources required to do this made its quality somewhat variable — for girls, it usually included domestic training to fit them for service; for boys in rural areas, training was largely in agricultural work. Some unions were more enthusiastic — Guiltcross in Norfolk even went as far as establishing a workhouse farm for the purpose. The children's cottage homes sites set up from the 1880s onwards also often included industrial training facilities.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.