Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire

Up to 1834

Sheffield Corporation's accounts from 1628 onwards record that they spent around £200 on the erection of a workhouse together with a stock of raw materials for providing employment. The construction of Sheffield's workhouse was based on others already in operation and the building's carpenters were sent to inspect the workhouse at Newark in Nottinghamshire. Sheffield's workhouse building was located on Workhouse Croft at West Bar, on what is now Paradise Street — another road at the north of the area still bears the name Workhouse Lane. The original workhouse was timber-built and stood in its own orchard. When the workhouse first opened, in about 1632, Nicholas Parkin was appointed "Master of the children," and there were bought "79 yards of blewish cloth for the apparelling of 20ty poore children putt into the Workehouse" for "cotes," and 98 "yardes of harden cloth" for forty "smockes". An expert was brought over from Chapel-en-le-Frith "to have taught children to knitt." A cow was purchased and the Master paid for agisting (grazing) it. The premises were gradually extended, with the addition of a school-house and a stable. At times, the workhouse seems to have been larger than was required for the accommodation of the poor, and some of it was let off in tenements. Robert Fisher rented a part in 1638, and in 1660 it was agreed "that Mr. James Fisher shall have and enjoy such roomes at the workhouse as were formerly in the occupation of Mr. Whittaker, under the yearly rent of three poundes."

In 1722, the town records note the "building of new Almshouses in West Barr" while 1733 saw the "first opening of the house of maintenance for the poor". It is not completely clear if these are references to the same site, but the latter is presumably to the brick building, enlarged in 1759, that was to continue in use until 1829.

Discipline in the workhouse was strict: in 1746, two of the female inmates, caught conveying a linen sheet and three breadths of blue lindsey to a receiver at the White Horse in Gregory Row, just over the yard wall, were first relegated to "the black hole," and afterwards "whipt," by order of the Overseers and Churchwardens. The Workhouse accounts contain many evocative entries, e.g., "1759. To William Roberts's funeral, 1s. 6d.; to bread for the same, 1s. 6d.; for bleeding a child with horse leeches, 2d.; for the books carrying to church, 4d."

By 1776, the Sheffield workhouse could accommodate up to 160 inmates. A report in 1795 by Sir Frederic Eden noted that:

Of the Poor of Sheffield, 148 persons, (who are mostly old and infirm, lunatics, soldiers' wives, or young children,) are, at present, in the work-house. Some of them are employed in spinning wool and lint, for flockings, shirts, sheets, and other articles for the use of the house. Men, who are able to work, are sent out to various employments in the town. The earnings of the work-house are, upon an average, about £170 a year.

The work-house is situated in an airy part of the town. The staircases are narrow and steep: the lodging-rooms about 9 feet 6 inches square, with 2 beds in each; except in one, which is rather larger, and contains 6 beds: the beds and pillows are filled with chaff: each is provided with 2 coarse Sheets, a coverlet, and 1 blanket, of the woollen manufacture of the house. The whole number of beds is 43. Two, three, and, sometimes, even four, Paupers sleep in a bed.

The following is the usual bill of fare: it is, however, somewhat varied in summer, when milk-pottage is occasionally served for breakfast and supper.

| Breakfast. | Dinner. | Supper. | |

| Sunday, | Water-pottage, gravy, (forming a sort of soup,) and bread. | Beef, bread, broth, and potatoes; or cabbage, and beer. | Broth and bread. |

| Monday, | Same as Sunday. | Puddings and sauce, and beer. | Bread and beer. |

| Tuesday, | Same as Sunday. | Same as Sunday. | As Sunday. |

| Wednesday, | Same as Sunday. | Same as Monday. | As Monday. |

| Thursday, | Same as Sunday. | Same as Sunday. | As Sunday. |

| Friday, | Same as Sunday. | Same as Monday. | As Monday. |

| Saturday, | Same as Sunday. | Cheese, bread, and beer. | Milk-pottage, and bread. |

The Poor are allowed to carry their breakfasts and suppers into their lodging-rooms ; but must eat their dinners in the hall, and leave on the table what they cannot consume. 3 oz. of cheese are allowed, on cheese days, to grown persons. The dinners, at Easter, and Whitsuntide, are veal, bacon, and plum-pudding.

The old people dine first: what they leave, forms part of the dinner of the children. The food is plentiful and good.

The West Bar area has been greatly altered and redeveloped in recent times but a car park records the former presence of the workhouse in the area.

Sheffield's Workhouse Lane car park, 2010.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1812-15, during a national shortage of coins, Sheffield was one a several urban workhouses at that period to issue poor relief in the form of specially minted tokens which could be used at local shops and then redeemed by shop-keepers. The coin depicts a large building which was presumably the workhouse in use at the time.

Sheffield 1815 workhouse token.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1829, a former cotton mill on Kelham Street at the north of Sheffield's city centre, was purchased at a cost of £7,500 to replace the Workhouse Croft establishment. The new premises could house about 600 inmates. The old workhouse site was then sold for £970.

Kelham Street workhouse site, 1849.

The Kelham Street workhouse clearly catered for a wide variety of inmates as indicated by the presence of blocks marked Hospital, Asylum, and Boys' School.

In 1777, a parliamentary survey recorded workhouses in use at Attercliffe with Darnall (for up to 24 inmates) and Brightside Bierlow (24 inmates). In 1822, Eccleshill had a workhouse on Sharrow Moor.

The township of Brightside had its own workhouse in Pitsmoor, at the east side of Rock Street. The building was erected in 1801 at a cost of £1,140 and replaced an earlier one also at Pitsmoor. It was a substantial establishment, complete with its own porter's lodge, and could accommodate up to 250 although the average number in 1835 was 58. In 1836, the Governor, rate collector, and vestry clerk was Mr George Sykes, and the matron was Mrs Housley.

Brightside workhouse site, 1849.

After 1834

Sheffield Poor Law Union was officially declared on 30th June 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 11 in number, representing its 3 constituent townships as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

West Riding: Attercliffe-cum-Darnall (2), Brightside Bierlow, Sheffield (8).

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 71,720 — Attercliffe-cum-Darnall (3,741), Brightside Bierlow (8,968), and Sheffield (59,011). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-6 had been £13,599 or 3s.10d. per head of the population.

The new Sheffield Union decided to continue using the Kelham Street workhouse and also retained the Brightside workhouse which was used for the accommodation of children.

The Kelham Street workhouse was enlarged in 1843 at a cost of £6,000. However, the building increasingly suffered from overcrowding, and also had no provision for caring for the sick. In 1855, the Sheffield Board of Guardians were visited by the Poor Law Inspector for the district, Mr Farnham, who strongly encouraged them to build a new workhouse. The following year, the Board set about buying land for a new building. However, the local ratepayers were strongly opposed to the scheme and in 1856 and 1857 voted out the old members of the Board. In the end, £6,000 was spent on alterations at Kelham Street. In 1874, the Board proposed buying additional land at Kelham Street to expand the workhouse site. However, the Local Government Board vetoed this and instead a green-field site at Fir Vale was found on which to erect a new workhouse.

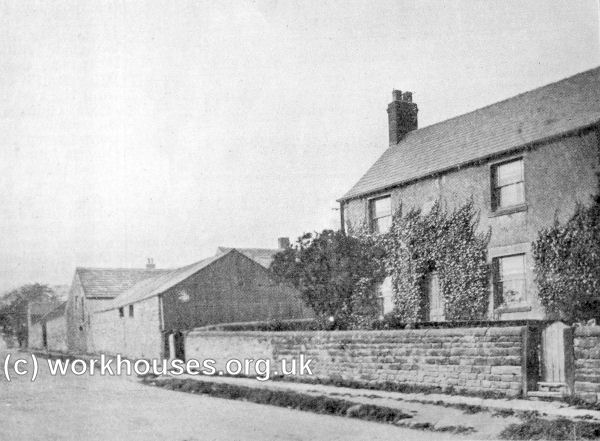

Hollow Meadows Workhouse / Industrial School

In 1848, the Sheffield Guardians leased from the Duke of Norfolk about fifty acres of moorland, at Hollow Meadows, about six miles from the town, with a view to reclaiming it by pauper labour. An ancillary workhouse was established on the site. Nearly the whole of the land was brought under cultivation and sub-let to farm tenants. "The Farm", as it was called, was retained by the Guardians and, in times of bad trade, able-bodied men in need of poor relief were sent to labour at it.

The new venture was the subject of a report by The Builder magazine:

Sheffield Hollow Meadows Builder report, 1848.

© Peter Higginbotham.

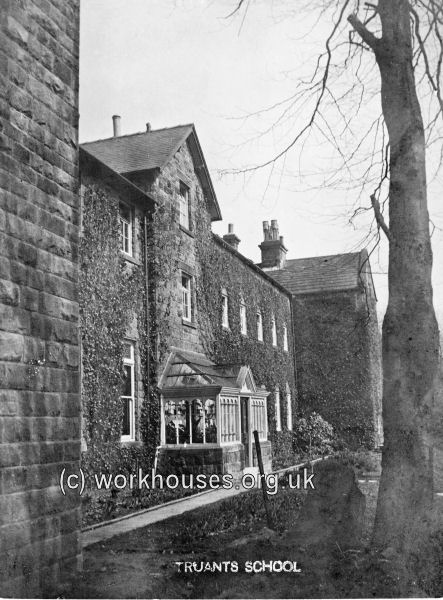

In 1879, the workhouse site became the Sheffield Truant Industrial School for Boys where persistent school truants were detained. The buildings were enlarged in 1887 and could then accommodate around 90 children.

Sheffield Hollow Meadows site, 1854.

Sheffield Truant Industrial School, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

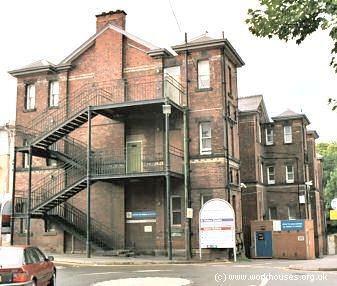

Sheffield Hollow Meadows site from the south-east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The site later became Hollow Meadows Hospital which was closed by 1981. The site was then sold for redevelopment and the buildings have now been converted to housing.

Fir Vale Workhouse

The 44.5 acre site at Fir Vale was purchased in September 1874 at a cost of £16,800. The new workhouse, which was expected to have a total cost of £180,000, was designed by James Hall. The foundation stone for the building was laid on 16th September 1878 by Alderman Searle, Chairman of the Sheffield Guardians.

The formal opening was almost exactly three years later, on September 22nd 1881, although the workhouse had actually already been in use since the previous year. At the time of the opening 1,188 paupers were in residence in the main building, with a further 365 in the hospital. The opening ceremony took place in very bad weather at 3pm when a large party of invited guests were given a tour of the buildings by Alderman Richard Searle (Chairman of the Guardians), Mr Spencer (Clerk), Mr John Heastie (Workhouse Master), and Mrs Annie Heastie (Matron).

A contemporary account relates that:

At 5pm, the guests dined in the Committee Room, after which Alderman Searle formally declared the workhouse open and gave a speech in which he said:

After other toasts and speeches, the evening concluded with a performance by Mr H Makin and his Glee Party.

The new building had six main sections:

- A main building which would accommodate up to 1,800 inmates.

- An asylum to the south, accommodating a total of 200 in two pavilion wings, mean at the east, women at the west.

- A school building for 200 children, situated to the north.

- A hospital building to the west, accommodating 366 patients in a number of pavilions.

- A fever hospital, further to the west.

- Vagrants' wards at the south-eastern entrance to the site.

The layout of the site can be seen on the 1890 map below:

Fir Vale workhouse site, 1890.

Fir Vale entrance gates, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Fir Vale main building from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Fir Vale main building entrance from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Fir Vale hospital pavilions from the north-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Fir Vale fever hospital from the east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Fir Vale school building from the south-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

An insight into life at the Fir Vale workhouse is provided in a report in August 1896 by Mr Rutherfourd John Pye-Smith, Emeritus Professor of Surgery at Sheffield University, and Consultant at the Royal Hospital. In the course of an investigation of the workhouse system, he visited Fir Vale and his account of what he found was sent to the Editor of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph. His lengthy report can be viewed on a separate page.

The diet in the workhouse at the time of Mr Pye-Smith's visit comprised:

- Breakfast (at 6.30am in summer, 7.30am in winter) — milk porridge and bread, or coffee and bread on Sundays. The elderly were allowed butter and tea instead of porridge

- Dinner (at noon) — boiled beef and potatoes, or hash (meat/potatoes/onions), or thick soup, each of which was served two or three times a week. Occasionally fish replaced the boiled beef.

- Supper (at 6pm) — as breakfast.

Meals were eaten in the large dining hall where males and females were segregated. The tip-up seats created a lot of noise when the inmates stood up.

Fir Vale rear of main building and dining hall from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1896, in order to provide work for the inmates and also a source of cheap fresh food, the Guardians took out a lease on Doe Royd Farm at Parson Cross. A Farm Committee was formed to manage its 160 acres and by 1903 the farm was running at a profit and also supplying all the workhouse's milk requirements. In 1906, Longley Hall Farm was also acquired for the sum of £10,500.

Doe Royd Farm, Parson Cross, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Doe Royd Farm Committee, Parson Cross, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A nurses' home was erected in the late 1890s at the south-west of the workhouse.

On 21st March 1906, the Local Government Board issued an order to separate the hospital from the remainder of the site, renaming it Sheffield Union Hospital. It gradually became known as Fir Vale Hospital. After 1912, the workhouse officially became known as Fir Vale House Poor Law Institution.

Fir Vale inmates, c.1910.

Courtesy of Northern General Hospital Archive, Sheffield.

In 1925, the Sheffield Union absorbed the neighbouring Ecclesall Bierlow Union, creating a single Poor Law authority to cover the whole of Sheffield.

On 1st April 1930, control of the workhouse passed to the Sheffield Public Assistance Committee who renamed it Fir Vale House. On the same date, Fir Vale Hospital came under the control of the Council Health Committee who changed its name to the City General Hospital. After the inauguration of the National Health Service in 1948, the whole site became the City General Hospital, then in 1967 was renamed the Northern General.

Fir Vale site, 1923.

Lyn Howsam's study of Fir Vale reveals that virtually the only record of workhouse life is the punishment register:

Punishments ranged from meals consisting of just bread and water to that of being sent to D block and passes were stopped occasionally, or sometimes for good, for the more persistent offenders. Some were eventually classed as too ill or infirm to be ever allowed out again.

Classes D block (later known as Ward 28/Dryden) was for all those who were decidedly bad. The accommodation was purposefully inferior with forms rather than seats. Older, patched clothing was used for the inmates. Luxuries such as broth, sugar, tea, butter and cheese were denied the inmates and there were no extras allowed such as snuff or tobacco. The punishment cell would accommodate the offender until the Master took action. Crimes also included swearing, refusing to work and violence.

Mr C L Marshall, Lodge Porter, who retired in 1965, commented in the Hospital Journal — 'Whenever I visit Dryden Ward I remember the time it housed 276 men of all characters completely lacking entertainment; they remedied this by amusing themselves singing and playing the mouth organ. The supreme form of entertainment was the boxing booth. This was composed of two heavy tables laid side by side acting as the ring. The contestants wearing their waistcoats, having placed their legs through their armholes making them appear as shorts. The timekeeper had a watch and an old fashioned spittoon as a gong. Charge for admission was one cigarette, mostly hand-rolled from tea-leaves. On occasions the doctor came along and was allowed in for free. Many of the contestants were professional boxers. (This was the late 1920s.)'

Those arriving at Fir Vale were greeted by:

A large building at the very top of the drive was where the older men, now disabled and unable to look after themselves were housed. They mostly had no relatives and were no longer able to work in the gardens. On the ground floor was a very large room with a wooden floor around which was placed wooden armchairs their backs against the walls. Each man had his own chair. Meals were eaten at the long tables and the only pleasure were boxes of dominoes donated by a charity. The days, weeks and months must have seemed endless. Beds on the wards were close together with no room for private possessions. Clothes were taken from a communal pile of clean shirts, trousers, vests, pants and socks. It was hit and miss as to whether they would fit. Once a week everyone had a bath and it was written down in a book with the date and the time. Young girls, who became pregnant out of wedlock, would be turned out onto the streets by their families for bringing shame on them all. They would turn up at the workhouse where they would be taken to one of the closed wards. When their babies were born they were taken away from them. These girls were classed as being of loose morals and were kept locked up. Eventually they became institutionalised and unable to look after themselves.

Life at the workhouse wasn't without its lighter moments however. By the early 1900s, a sports day was held each year with races held on the ground at the east of the main building.

Fir Vale Sports Day, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A 1902 Photo Album

A vivid glimpse of life at Fir Vale is provided by a unique collection of photographs taken in 1902, after Duncan Ernest Elijah Burgess and his wife Eliza Ann (née Lewis) became Master and Matron. Their great-granddaughter Pamela Repussard has very kindly allowed their reproduction here. In 1881, Duncan had been working at the West Derby Workhouse, Walton on-the-Hill, and Eliza was at the Union Workhouse School at Kirkdale, Lancs. In 1893 they were married in Walton, then in 1895 became Master and Matron of Fulham Workhouse, London. At some point they were in charge at Skipton Workhouse, then in 1902 took over Fir Vale. Sadly, Eliza died later that year and Duncan then left to become a 'gentleman farmer'.

Fir Vale entrance to main building from the east, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale men's ward, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale women's ward, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale women's ward (detail), 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale Lying-in Ward, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale Lying-in Ward, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale nursery, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale nursery (detail), 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale kitchens, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale nurses' home, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale staff sitting room, 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Fir Vale staff sitting room (detail), 1902.

© Pamela Repussard.

Scattered Homes

After the opening of the new workhouse, the Sheffield Guardians turned its attention to finding the most satisfactory way of caring for its pauper children. In 1888, 40 children were placed in private homes in a "boarding-out" scheme — what we would now term fostering. Plans were then developed for a new scheme of care which was to become widely adopted by other unions. The "isolated homes" system was devised in 1893 by J Wycliffe Wilson, Chairman of the Sheffield Board of Guardians. Isolated homes, or scattered homes as they became more commonly known, placed small groups of children in ordinary houses scattered around the suburbs of the city, under the care of a foster-parent employed by the union. Unlike cottage home village sites which usually had their own schools, the children in scattered homes attended ordinary local Board schools and mixed with other children in the local neighbourhood. The placing of homes was arranged such that there were never more than 30 scattered homes children attending any one school. The first homes were opened in October, 1893.

A 1907 Report by Report by the union's Children's Homes Committee outlined the main features of the scattered homes system as follows:

- It ensures that no children over the age of three ever enter the Workhouse. It is applicable to ALL children, not to "Orphan and Deserted" only.

- It provides Homes for the children approximating as closely as possible to the conditions of working-class life.

- It secures a training and development on natural lines apart from pauper associations and artificial arrangement.

- It keeps the children within reach of the effective oversight of the Guardians and their officers.

- It scatters the children among the ordinary population in different suburbs of the city, and prevents the aggregation of any large number in one place.

- It permits the attendance of the children at Public Elementary Day Schools in numbers sufficiently small to prevent their presence being specially noticeable.

- It results in the attendance of comparatively small numbers at a considerable number of different Churches, Chapels, and Sunday Schools.

- It allows the children the opportunity of attending Evening Classes, Bands of Hope, and other Juvenile Societies along with other children.

- It secures the mixing of the children with boys and girls occupying superior social positions, as companions and friends.

- It secures some of the best features of the Boarding Out and Village Cottage Homes Systems.

- It secures the interest, and in some cases the active co-operation, of some of the best men and women in the city.

- It is applicable to all large Unions, and with some slight modification to small ones also.

A Central or Headquarters home was located on Smilter Lane (now Herries Road), at the south of the main workhouse site (see map above). It included three children's houses used for those children who were frequently in and out, or whose behaviour required close attention. The three homes, known as Rose, Hawthorn and Ivy Cottages, had bare floors and hard beds, but were also light and airy, with plastered walls, and were decorated with pictures and flowers.

Southern part of Fir Vale site, 1905.

The Headquarters Home acted as an administrative and supply centre for the other scattered homes, and also provided a receiving house for accommodating up to twenty new arrivals. The site incorporated an old house called Goddard Hall, initially used as a home for Roman Catholic children, and later used as a communal building and fitted out with a tailor's shop in which to provide training for the boys.

Sheffield HQ Homes - Goddard Hall, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The opening of the Central Homes in November 1894 was the subject of a report in the Building News:

Sheffield HQ Homes - commemorative plaque, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

New arrivals at the receiving house were given a bath, haircut, and medical inspection. Their own clothes (often only rags) were sent to be laundered and stored, although had to be worn if the children visited their own parents. The children, unless suffering from health or other problems, were then assigned to one of the scattered homes.

Sheffield HQ Homes from the south-west, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The villa-style superintendent's residence was known as Chesterman House.

Superintendent's house from the west, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The children's section, rather more institutional in character, was named Wycliffe House.

Sheffield HQ Homes children's quarters from the south-east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A block at the east of the complex house a wash-house, laundry and stores. The stores also held supplied for all the individual homes around the city.

Sheffield HQ Homes stores from the north-west, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Sheffield HQ Homes laundry from the east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A separate children's hospital building was included in the scheme at the north of the homes, shown in the picture below.

Children at the Sheffield HQ cottage Homes, 1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Although none of the headquarters' children's houses survive, one of the original playshed/washhouse blocks from the rear of the houses still exists.

Sheffield HQ Homes - playsheds/washhouse, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Initially, nine scattered homes were set up, each containing between fifteen and twenty-eight beds. Seven were allocated to Protestant children, and two to Roman Catholics. Each house was presided over by a foster mother, assisted in the household work by the elder children and an occasional charwoman. By 1911, the number of homes in the scheme had risen to around 30 as listed below:

| Home no. | Address | Foster parent(s) |

| 1 | 12 Upperthorpe | Miss Hannah Evans |

| 2 | 14 Upperthorpe | Mrs G Gelder |

| 3 | 149 Upperthorpe | Miss A Gilbert |

| 4 | 151 Upperthorpe | Miss Ethel J Dronfield |

| 5 | 14 Abbeyfield Road | Miss Sarah Annie Stringer |

| 6 | 16 Abbeyfield Road | Miss Lucy Woodhead |

| 7 | 92 Andover Street (boys) | Mrs Bertha Woolhouse |

| 8a | Daisy Cottage (RC), Smilter Lane | Miss H Donavan |

| 8b | Fern Cottage (RC), Smilter Lane | Miss E Byron |

| 9 | Ivy Cottage, Smilter Lane | Mr & Mrs Thomas Leeming |

| 10 | Rose Cottage, Smilter Lane | Miss M Morton & Miss Artindale |

| 11 | Receiving House, Smilter Lane | Joe Fawcett Sykes (Supt); Mrs Mary Sykes (Matron); Mr & Mrs Thomas Slater |

| 12 | 279 Grimesthorpe Road | Mrs Jennie Crooks |

| 13 | 281 Grimesthorpe Road | Miss Susie Martin Coleman |

| 14 | 71 Scott Road | Miss Harriet Eyre |

| 15 | 73 Scott Road | Mrs Mary Emma Whitehead |

| 16 | 399 City Road | Miss Florence Hobbis |

| 17 | 401 City Road | Mrs Alice Turton |

| 18 | 15 Manor Lane | Miss Clara Mallender |

| 19 | 17 Manor Lane | Miss Mary Colley |

| 20 | 521 City Road | Mrs E Letts |

| 21 | 523 City Road | Miss SA Haslam |

| 22 | 75 Duchess Road | Miss Kate M Nicholson |

| 23 | 77 Duchess Road | Miss Annie Hawkins |

| 24 | 278 Edmund Road | Miss Harriet M Teeling |

| 25 | 280 Edmund Road | Miss Kate Stewart |

| 26 | 110 Heeley Bank Road | Mrs Agnes Mary Girdler |

| 27 | 112 Heeley Bank Road | Miss May Lowe |

| 28 | 196 Heeley Bank Road | Miss Laura Gibbons |

| 29 | 198 Heeley Bank Road | Miss MA Nuttall |

Sheffield scattered homes (149-151 Upperthorpe), 1898.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Sheffield scattered homes, 1898.

© Peter Higginbotham.

14-16 Abbeyfield Road - one of Sheffield's first scattered homes, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Despite being "ordinary" houses, most of Sheffield's scattered homes were purpose-designed as shown in the plan below.

Sheffield scattered homes design (side elevation), c.1898.

© Peter Higginbotham.

279-281 Grimesthorpe Road, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Scott Road homes had a different though distinctive design.

71-73 Scott Road, 1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

71-73 Scott Road, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Although the foster parents were carefully chosen, several instances occurred of a foster parent beating a child, or instructing other children to do so. In January 1896, Mr and Mrs Hunt — foster parents in the Central Home — were dismissed after a boy was roughly treated. The children's teeth were sometimes neglected. Mr Tolputt, a dentist employed by the Guardians, found that in one house there were only seven toothbrushes between twenty-two boys. An official inspection of the homes in May 1896 found that four out of fifteen house-mothers, and five out of eight married couples, had resigned as listed in the following table.

| No. of Home. | Foster-Parents | Still in Office. | Resigned. | Cause of Resignation as stated by Superintendent. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mother | No | Health broke down and not sufficiently energetic. | ||

| 2 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 3 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 4 | Mother | No | Yes | Mother was a wife separated from her husband. Asked to resign because she continued to invite to the home a man whom she could not marry. | |

| 4 | Mother | No | Yes | Ill-treated children and did not keep their heads clean. | |

| 4 | Mother | In charge of another home | |||

| 4 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 5 | Mother | No | Yes | Stayed away all night without leave. | |

| 5 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 6 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 7 | Father and mother | No | Yes, recently. | Mother's health, failed. (The clothing of the boys seen by us at this home showed much-went of care.) | |

| 7 | Father and mother | Yes, just appointed. | |||

| 8 | Father and mother | No | Yes | Both incompetent. | |

| 8 | Father and mother | No | Yes | Incompetent. | |

| 8 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 9 | Father and mother | Yes | |||

| 10 | Father and mother | No | Yes | Both ill-used the children. | |

| 11 | Mother | Now a relief mother | |||

| 11 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 12 | Mother | Yes | |||

| 13 | Mother | Yes | |||

| Receiving House | Father and mother | No | Yes | Incompetent. | |

| Receiving House | Father and mother | Yes |

The inspectors' report suggested that the salary paid to house parents (£18 a year for a mother, £40 for a married couple, with board and lodging) should be reviewed. The report made a number of detailed criticisms of the operation of the homes, such as a lack of mixing with local children outside of school, arrangements for parental visits, and the presence of nits on some children's heads. However, the report concluded:

On 26th March 1942, the premises at 71-73 Scott Road re-opened as a Girls' Hostel. There was accommodation for 14 female girls over the age of 15, most of whom worked out in the community.

Smilter Lane Aged Homes

In 1896-7, a block of eight single-roomed cottages, known as Fir Vale Cottages, was erected at the east of the Children's Central Home on Smilter Lane. The homes were formally opened in October 1867 by the Lord Mayor of Sheffield (the Duke of Norfolk) who was presented with an inscribed silver key. Each room measured fourteen feet by eleven feet and accommodated aged and infirm people of good character over the age of 60, either a married couple, two men, or two women. A caretaker's house lay at the centre of the block, with four cottages at each side.

Sheffield Aged Homes, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Staff

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1881 Census — Kelham Street Workhouse

- 1881 Census — Fir Vale Workhouse

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Sheffield Archives, 52 Shoreham Street, Sheffield S1 4SP. Holdings comprise: Guardians' minute books (1890-1930 with gaps), Punishments register. The majority of the Sheffield Union records are said to have been destroyed when the former Union offices were bombed during World Ward 2.

Bibliography

- Drinkall, Margaret (2011) Sheffield Workhouse.

- Howsam, Lyn (2002) Memories of the Workhouse & Old Hospital at Fir Vale.(ALD Design & Print. ISBN 1-901587-22-3)

- A Brief History of The Smilter Lane/Herries Road Scattered Homes. Fir Vale Workhouse Sheffield. Produced by the Sheffield Hospitals History Group. Price £5.50 plus UK P&P. Contact lyn@howsam.co.uk.

- Howsam, Lyn (2006) Life in the Workhouse & Old Hospital at Fir Vale.(ALD Design & Print. ISBN 1-901587-60-6. £6.95). Email lyn@howsam.co.uk for further details.

- The Institution and Hospital at Fir Vale: A Centenary History of the Northern General Hospital. P. Speck et al. (1978).

- Leader, R.E. (1905) Reminiscences of Sheffield in the Eighteenth Century

Links

- Northern General Hospital Archive Project — contributions welcome.

Acknowledgments

- Many thanks to Lyn Howsam for her contribution to this page, to Northern General Hospital Archive Project for the cottage homes report extracts, and to Pamela Repussard for the wonderful photos.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.