Liverpool, Lancashire

Up to 1834

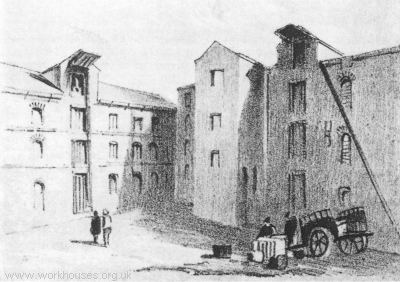

Founded in 1732, Liverpool's first parish workhouse was erected at the corner of College Lane and Hanover Street.

Liverpool's 1732 workhouse.

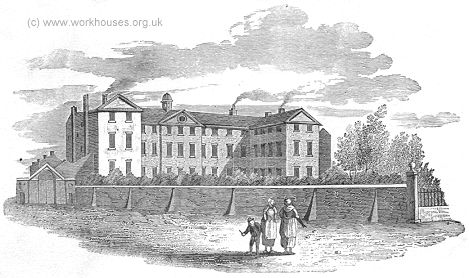

A new "House of Industry" was built in 1769-72 at Brownlow Hill. A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded Liverpool Borough as having a workhouse that could accommodate up to 600 inmates.

In 1796, a fire at the workhouse destroyed one of its wings. The following year, Liverpool was the subject of a report in Eden's 1797 survey of the state of the poor in England:

Liverpool House of Industry from the north, c.1800.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1823, three remarkably long-lived workhouse residents died: Ellen Tate aged 110, Francis Dixon aged 105, and Margaret McKenzie aged 104. In 1824, there were 1,073 persons in the workhouse.

In 1832, as part of Royal Commission's nationwide investigations into the operation of the poor relief, Assistant Commissioner Gilbert Henderson visited Liverpool workhouse. He was clearly impressed by what he found and by what the governor had achieved through a regime that included segregation of the sexes, a twelve-hour working day, and almost constant confinement to the premises. This, together with a curtailment of out-relief in favour of offering the workhouse, had resulted in the local poor rate in Liverpool for 1832-3 being only 4s. compared to the national; average of 9s.9d. Extracts from Henderson's report is included below.

The children, nine years of age, are taught to weave, and their time is divided between school and the looms; under this system they thrive better, and the instruction they get in weaving promotes their being apprenticed. The choice of the children is complied with as far as possible in apprenticing them; some are bound to tradesmen, tailors, shoemakers, &c., some go to sea, but the largest proportion, until recently, went to cotton factories, where most of them were bound to persons of respectability ; on leaving the workhouse, they are told to send information if they are not well treated. It is easy to ascertain how those fare who were apprenticed in Liverpool, and the others are visited by some of the overseers usually every year, but at all events once in the course of two years. The apprenticing and visitation of the children is occasionally adverted to in the Reports of the select vestry. Instances not unfrequently occur of individuals who have served their time with credit, calling at the workhouse or at the select vestry, and stating that they are able to earn a comfortable subsistence.

The inmates of the workhouse were formerly allowed to go out every Thursday afternoon ; this permission led to many irregularities, the paupers frequently returning drunk, and begging or otherwise misconducting themselves in the streets to the scandal of the establishment. They also used to go out on Sundays to church, but a chapel has been built within the work- house and a regulation was adopted in 1831, which restricted the liberty of leaving the house to the first Thursday afternoon in every month, except in the case of paupers upwards of sixty years of age, who are still permitted to go out every Thursday. The Catholics go out to chapel at eight every Sunday morning, and return at ten. Thus, one condition of entering this workhouse is submission to constant confinement, except for a few hours every month.

The rooms are well ventilated, floors kept clean, and sprinkled daily with chloride of lime, and the walls frequently whitewashed. Although the cholera has been so prevalent in Liverpool, only nine cases occurred up to Sept. 6, 1832, in this establishment; four of these proved fatal, one being the case of a pauper who, before his admission, had been employed as a bearer of the litter in which cholera patients were carried to the hospital.

The governor lays great stress on classification generally, and on a complete separation of the sexes ; there are lock-wards for males and for females in this establishment, and the governor thinks them essential to prevent the most depraved inmates corrupting or annoying decent and orderly paupers : in the small houses, in which two or three married couples live together, those of congenial habits and character are placed together.

When the workhouse was visited, some of the boys and girls were busy weaving, but the greater part of them were in a spacious school-room under the chapel ; their general appearance was satisfactory : the oakum-shop was almost filled by men seated on benches and picking oakum. The hours of work are from six in the morning to six in the evening in summer, and from eight until four in winter, allowing half an hour for breakfast, and one hour for dinner; persons eighty years of age and upwards are exempted from any labour, but from all under that age and in health, a task is required in proportion to their ability and strength; those who, from age or infirmity, have a limited task, are allowed to choose their own time for performing it, and used formerly to pick the oakum in their own rooms; but owing to the risk of fire, this practice has been discontinued, and all this work must now be done in the shop. A full measure of employment is exacted from the able-bodied, the object being to discourage laziness, and, as the governor expressed it, to "work them out." The consequence is, that not more than twenty of the inmates were able-bodied men. The aged people appeared the most cheerful inmates ; the avowed principle of management is to make them and the young most comfortable. The women were all employed, chiefly in sewing, attending to the young children, acting as nurses, and performing household offices.

A general appearance of order and discipline prevails throughout the establishment. The governor, who is a steady systematic man, stated that 1000 or 1800 paupers were as easily managed as 500. He has two salaried clerks, a schoolmaster, and two weavers acting as overlookers, who receive salaries; and the governor's wife has two paid female assistants ; the rest of the establishment is conducted by paupers selected from the inmates.

A fever hospital, a detached building, for 140 patients, is supported by the parish, within the walls, and forms part of the workhouse establishment ; the diet, wine, &c. for the patients, materially increase the general expenditure; female paupers act as nurses, and having some privileges in consequence, are usually desirous to be so employed. The total weekly cost, including provisions, clothing, and all the expense of the establishment was last year, 3s. 2d. per head ; but as there was an extraordinary item of 1426l. for buildings, perhaps 3s. may be considered a fair estimate, communibus annis. The weekly cost for provisions and clothing was 2s. 2½d. per head.

The following tables show the fluctuation and employments of the population in the workhouse:—

| On the 25th of March, 1831, there were in the house | 1696 | |

| During the year ending 25th of March, 1832, admitted | 2962 | |

| 4678 | ||

| During the year, Discharged | 2540 | |

| Dead | 477 | |

| 3017 | ||

| Remaining in the house 25th of March, 1832 | 1661 |

| Ages of the inmates: Under 15 years | 589 |

| 15 to 40 | 242 |

| 40 to 50 | 135 |

| above 50 | 695 |

| 695 | |

| 1661 | |

| Aged, infirm, and sick, not able to work | 437 |

| Aged and infirm employed | 426 |

| Able-bodied under sixty years of age employed (males 67, females 142) | 209 |

| Children employed | 159 |

| Children not employed | 430 |

| 1661 |

Of this number, 639 were males and 1022 females, the average number in the house throughout the year was 1648, being about 1 per cent of the population of the town.

After 1834

Prior to the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, poor law administration in Liverpool was conducted by a body known as a Select Vestry - a parochial body which had been formed under Sturges Bourne's Act of 1819.

As in many parts of northern England, Liverpool resisted the implementation of the 1834 Act, but Liverpool Poor Law Parish finally came into being on 25th March, 1841, under a 25-strong Board of Guardians. Its population (recorded in 1831) of 165,175 made it the largest in England. However, within a year, continued petitioning led to the passing by parliament of a Local Act providing for a reversion to its being managed by a Select Vestry. This continued in operation until 1922 when the Liverpool Select Vestry was dissolved and the area and institutions under its jurisdiction were added to the West Derby Union.

Brownlow Hill Workhouse

Liverpool Parish continued to make use of the Brownlow Hill site, whose layout is shown on the 1848 map below.

Liverpool workhouse site, 1840s.

The Brownlow Hill workhouse was enlarged in 1842-3 with Henry F Lockwood and Thomas Allom as architects. It grew to become one of the largest workhouses in the country with an official capacity of over 3,000 inmates (and accommodating as many as 5,000 on occasion).

Liverpool workhouse site, 1886.

Liverool Workhouse plan, c.1864.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Liverpool workhouse, Brownlow Hill, from the west c.1931.

The original building, at the south of the site, later became used as the workhouse infirmary.

Liverpool workhouse infirmary from the south, c.1925.

In February 1843, following claims that lax supervision at workhouse had resulted in it becoming the largest brothel in England, the Satirist published statements made at a recent meeting into the matter by a stipendiary magistrate, Mr Rushton. He had alleged that in the classification ward, abandoned profligates were living with decent people and there was indiscriminate prostitution going on; an access route had been created over the wall between the male and female wards by knocking off the glass bottles from the top, and women wearing only shifts were going over to the men during the night. It was also claimed that the governor was afraid to go into some parts of the workhouse at night.

On 7 September 7 1862, a serious fire at the workhouse destroyed the church and one of the children's dormitories. Twenty-one children and two nurses were burnt to death.

Liverpool workhouse fire, 1862.

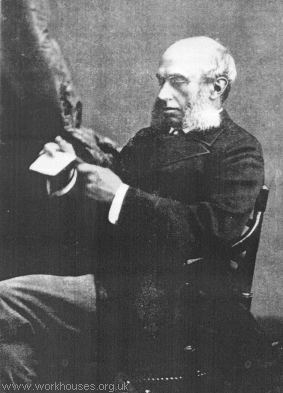

Liverpool pioneered the use of trained nurses in workhouses through an experiment in 1865 funded by local philanthropist William Rathbone. He financed the placement in the workhouse infirmary of twelve nurses trained at the Nightingale School. These were assisted by eighteen probationers and fifty-four able-bodied female inmates who received a small salary.

William Rathbone.

Although the experiment had mixed results — the pauper assistants needed constant supervision and obtained intoxicants at the slightest opportunity — it was generally perceived overall to have been a success, in large part due to the efforts of the infirmary superintendent, Agnes Jones. Eventually a skilled nursing system spread to all workhouse infirmaries in the country.

Agnes Jones.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In October and November 1866, the workhouse received several visits by Poor Law Board Inspector Mr R.B. Cane. Following a visit to the sick wards, he reported:

Some of the wards contain boys and girls only, but there is no effective classification as regards age, and youthful and quite young persons are to be seen in the wards with adult inmates. On the "men's side," the nursing is wholly performed by paid and "skilled " nurses, under a lady superintendent. On the "women's " side there is a staff of paid nurses, but the assistance of pauper attendants is allowed.

There are three resident assistant medical officers and two chief officers. The drugs, &c., are provided by the Guardians. Great care and attention appear to be paid to the sick, who seem to be fully supplied with everything that is essential to their condition. The cleanliness, neatness, and order of the wards cannot be excelled. In most of these wards, however, the beds are too close together. Many of the wards are seriously defective in regard to ventilation; some of them may be described as being in this respect in a bad, and some in a very bad state. The same remarks apply to the corridors, staircases, waterclosets, urinals, bath rooms, &c. The "traps" to the drains, too, seem to be out of order. Until these serious evils are effectually remedied, these wards cannot be in a satisfactory condition.

After a subsequent visit to the remainder of the workhouse he noted:

This house is situated at "Brownlow Hill," in Liverpool, and, although in a comparatively open part of the town, it is surrounded with buildings. There rs no ground attached to it, and there is no outlet for the inmates but the yards appropriated for each class of poor. All classes are to be found here; the principal numbers, however, consist of men, some few of whom are regarded as able-bodied, old and infirm men, aged and infirm women, able-bodied women, women with infants, and girls. The inmates ate, as far as possible, thus divided. and, classified.

There seems to be a very complete separation of girls from the able-bodied and other inmates; and the wards in which they are placed, under the superintendence of a mistress, who instructs them and teaches them such household work as will fit them for service, is one of the most pleasing and satisfactory departments in this establishment.

The small wards set apart for aged women of good conduct and character, and who reside three orfour together in each ward, with great apparent comfort, and as their dispositions, religion, country, and general habits induce them 'to associate, is a distinction peculiar to this workhouse. This subdivision of aged women, and the condition in which they are thus placed, is-highly gratifying.

The other inmates occupy day-rooms, work-rooms, and sleeping wards, which are large, well proportioned, and of good height, although the dormitories nearest the roof do not fully answer this description.

The beds and bedding are good in kind and in a proper state. Clean clothes are duly supplied to the inmates. There is a good and plentiful supply of water, and the wards are properly warmed by fires in open grates.

The offices and necessary work of the house give employment to the men who are capable of labour. A large number of able-bodied women are employed in picking oakum: washing, laundry work, scrubbing and cleaning, engage many others, whilst the less strong are occupied in mending clothes, looking after infants, &c.;

Upon the whole, and in so far as it was possible for me to form an opinion on a single visit to so enormous an establishment, I may report that it is generally in a satisfactory condition.

It, however, does not contain all the poor for whom it is necessary to provide in-door relief. Besides the school, several smaller houses, of a more domestic character, containing together from 400 to 500 persons, are in possession of the vestry. The pressure which has compelled the use of these houses for imbecile persons and others, shows the defects as regards size, us well as in the means for classification of this workhouse. No one would seriously propose to increase the extent of this house, even if it were possible to do so; and should the demand for workhouse accommodation increase, the vestry will probably find themselves obliged to provide that accommodation elsewhere.

The vagrant wards are not large enough, and ate now being altered and enlarged. There are not proper means for drying the clothes of vagrants in wet weather; a serious defect. The task of work approved of by the Poor Law Board is duly exacted, and men and women who are able to do so grind corn at a mill.

In 1895, following an explosion in a steam pipe at the workhouse which led to the deaths of three men, a new theory emerged as to the cause of the catastrophe. The blast had occurred when steam was being blown off from the main boiler into an underground tank. Subsequent inspection of the tank revealed the body of cat which, from its appearance, had not been there long. It was believed that the cat had somehow got into the tank and blocked an overflow pipe, causing a build-up of pressure and eventual explosion. The three fatalities, all resulting from the horrific scalding injuries they received, were the workhouse engineer, Richard Long, and two inmates who acted as stokers.

On 6th November, 1901, it was reported that the famous Nottinghamshire and England fast bowler John Jackson had died in the Liverpool workhouse infirmary his sixty-ninth year. Known as the 'demon bowler', Jackson's first-class career, which had extended from 1855 to 1866, had come to an end after he sustained a serious injury whilst playing against Yorkshire. He visited Australia in 1863-4, at which time he was regarded as one of the best fast bowlers in the kingdom. Despite a small allowance from the Cricketers' Friendly Society, and the help of friends, Jackson had spent his declining years without a permanent address and on the brink of the workhouse, whose doors he finally entered.

On 3 February 1911, Robert Tressell, author of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropist, died in poverty in the workhouse.

In 1922, the Poor Law administrations of the Parish of Liverpool and the Toxteth Park Union were absorbed by the West Derby Union.

The Brownlow Hill workhouse was closed in 1928 and then demolished in 1931 to make way for Sir Edwyn Lutyens' Roman Catholic cathedral.

Liverpool inmates' bathing regulations

Kirkdale Industrial School

In 1843, the Select Vestry erected an industrial school for the care and training of pauper children on what is now Westminster Road at Kirkdale.

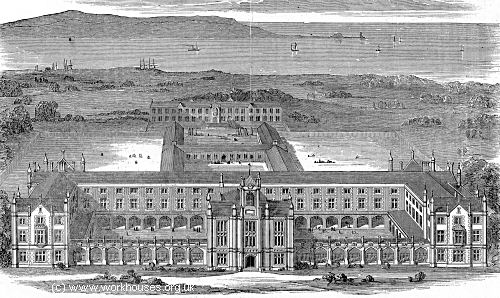

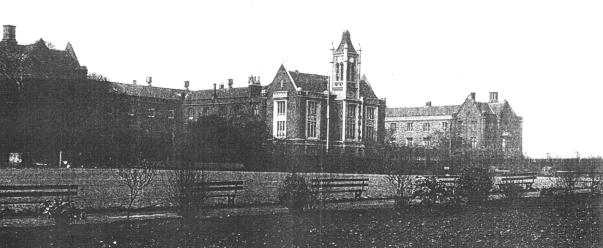

Liverpool - Kirkdale Industrial School, c.1850

In 1850, an article about the school in the Illustrated London Newsreported:

The erection of this handsome and spacious building, situated in Booth-lane, Klrkdale, near Liverpool, was commenced in June, 1843, and completed at a cost of upwards of £32,000. The style is Elizabethan, and the building (from the design of Messrs. Lockwood and Allom, of London) is considered one of the principal architectural ornaments of the vicinity of Liverpool. The whole cost of the erection was borne by the parish. It was found, for some years prior to its establishment, that the juvenile pauperism of Liverpool was so largely on the increase as to be incapable of being accommodated in the workhouse. It was accordingly determined, after long and anxious debates in the vestry, that Schools should be erected at some short distance from the town, where the young children thrown upon the parish should be located apart from the adult paupers, and instructed, not only in the elements of a plain education — reading, writing, and arithmetic — and in their religious duties, but in the most common and useful trades. The institution was opened May 1, 1845, and commenced with 300 to 400 scholars: at present It contains 1123 children, of whom 640 are boys, and 483 girls; the number is limited to 1150. The annual cost to the parish for their support and education ia £10,483 1s. 9d. The result of this experiment has been highly favourable in extending education among the destitute children of the town; but it has not been to relieve, as was intended, the workhouse from an overflow of juvenile pauperism. The workhouse still contains upwards of three hundred children, which is almost as many as it did before the Industrial Schools was founded. The trades which the boys are taught are tailoring, shoemaking, and carpentering. The girls are instructed in knitting and needlework, in washing, ironing, mangling, cooking, and general household work, to qualify them for domestic servants. For such of the boys as exhibit an inclination to go to sea, instruction is also provided. A ship has been erected on a portion of the grounds, where an old sailor teaches the aspirants for a maritime life the work required of young sailors on their first few voyages — everything, in fact, except steering, and such other matters as can only be performed upon the water. The boys generally seem to consider it a privilege to learn to be sailors ; and many of them, under the tuition thus acquired, have been qualified for, and have obtained, good situations on board ship. No compulsion is exercised upon them as to the trade which they shall learn. It is found, that, next to the sea, the tailoring business is the most popular among them. On the day of our visit we were introduced to an assemblage of about forty young tailors, sitting cross-legged, in the approved fashion, and all being engaged, under the superintendence of a foreman, to mending clothes for the whole establishment. Their labour is not sufficiently skilled or valuable to be employed in making their own garments. The labour of the female part of the establishment is turned to greater account ; and the girls not only mend, but make, the shirts and other articles required in the schools. What effect the annual training of so many tailors and sempstresses at the public expense may have in future upon the slop trade of the town, we shall not inquire ; although there are not wanting many who assert that its inevitable tendency is still further to overstock a labour market, so cruelly overstocked already as not to afford a bare subsistence to men and women who labour for eighteen hours a day. The establishment, however, is admirably conducted, and is a model of order and cleanliness. The boys have an excellent band, and have made such proficiency in music as to be able to perform several favourite airs and other pieces in a very creditable manner. The schools offer so many advantages to poor children, that it has become an object of ambition among many people, who are not paupers, to get their children introduced into it. This is an ambition, however, which the parish finds it essential to thwart, under the penalty of being overwhelmed with claimants, and of being justly charged with offering — a premium upon parental neglect. Mr. Rushton, the able and humane stipendiary magistrate of Liverpool, in a very valuable letter addressed to the Town-Council, on the 28th of February last, upon the question of juvenile crime in the town, gives his cordial approbation to the Industrial Schools, and states that "he knows of no institution which has done more good — whether that good be estimated by the blessings it has conferred upon the inmates, or by the evil it has prevented to the community." Mr. Rushton, than whom no man his had more practical experience of the evils which he wishes to remove, cites in his letter the case of 14 juvenile criminals, whose prosecution and maintenance in prison cost the parish, at successive times, no less a sum than £889 1s., independently altogether of the amount of their depredations upon the public when out of prison; and earnestly urges upon the attention of the Town-Council the expediency and the policy of going to the root of Juvenile crime, and preventing it, by means of education, which will be in every respect a better, and what to some minds may be a very important consideration, a cheaper process.

Liverpool - Kirkdale Industrial School c.1960

Kirkdale, too, was visited by Poor Law Inspector Mr R.B. Cane in September 1866 at which time it house 1,250 inmates. His report concluded:

I am unable to report that this school is in a satisfactory state.

The want of space has rendered it necessary to fit up portions of the day-rooms as sleeping rooms, and a large number of beds occupy, to a considerable extent, the places in which it was intended that the boys and girls should take exercise in wet or severe weather. The same deficiency has led to the use of one of the lesser wards, in the main body of the building, as an itch ward. There are no receiving wards, a serious defect.

The sleeping wards have not been constructed in a manner well-calculated to afford good ventilation, and the defect is sensible at the present time to any one who passes through these wards. A strong ammoniacal smell is perceptible, showing that ventilation is not good; this condition partly arises from the wards being too full; the beds are are in some of the wards so close together as almost to touch; some of the bedsteads are constructed to hold three children; they are only separated by a thin partition; these bedsteads are also to be found in the infirmary, where they are likewise used. The close, disagreeable, and unwholesome atmosphere of some of the sleeping wards is aggravated by "wet beds," of which I found a considerable number; these beds are not removed and changed daily, as they should be; they are allowed to remain on the bed-steads; it is supposed that in the course of the day they become dry and fit for use, a result which I am satisfied does not take place, and therefore these beds are rarely, if ever, in a proper state; the floor beneath some of the beds was saturated with urine; the master stated that he could not remove these beds front the wards, because he had no place to dry them in ; the yards and other parts of the premises are in an untidy and slovenly state.

Note.—When the new and additional buildings now in progress are completed, these defects will doubtless be fully remedied.

Liverpool - Kirkdale Industrial School

The new buildings mentioned by Cane lay to the south of the site and were completed in October, 1868. They were the subject of a report in The Builder on the 10th of that month.

The new buildings, which are quite distinct from the old schools, have been erected from designs by Messr Picton & Son of Liverpool, architects. They stand on high ground, in the immediate vicinity of the county prison. The style adopted is Gothic. The principal elevation, which faces the south, is 357 ft in length and 40 ft in height to the battlements, and consists of three stories. In the centre is a tower, which rises 68 ft above the battlements. Beneath this, and over the main central entrance, is a large ornamental oriel window, below which again there is a prominent three-light window. At each side of the main entrance there are two carved figures in stone representing Charity and Mercy. At the east and west ends of the building respectively there are pavilion roofs, which rise to a considerable height. The east and west elevations of the buildings are uniform in design, with the south front, the school-room dining and play rooms, having mullion chancel windows. The rear of the building forms a large quadrangle, there being, in addition to the east and west wings, what may be termed a centre wing, containing school rooms, play rooms, and dormitories, uniform with the other portions of the building. The main south entrance leads to a corridor 7 ft. in width, which runs the entire length of the building, from which, in the front part, on the ground floor, are approached the several day-rooms, teachers' rooms, offices, and other rooms in the master's department. From the opposite side of the corridor, in the centre, a play room is entered, 73 ft in length, by 30 ft. in width, with an additional play-shed beyond it, 75 ft by 30 ft. The principal school-room is in the east wing of the building, and is 83 ft long by 30 ft. wide and 36 ft in height; whilst the dining room, which is in the west wing, is 80 ft.long by 30 ft. wide and is uniform in height with the school- room. Two staircases, one at the east and the other at the west end, lead from the ground floor to the first floor, along which there is a corridor exactly uniform with that already described. The whole of the first floor is divided into dormitories of uniform size, for the use of the officials of the establishment as well as the inmates. The upper story is approached by a staircase similar in size to the one beneath it, and a uniform corridor leads to three large dormitories similar in size to the large school-room, dining-room and play-room on the ground floor, in addition to which there are also a number of smaller dormitories.

With the view of promoting ventilation there are iron gratings on each side of the entire length of the two upper corridors, by which a constant current of air is kept up from the ground floor, whilst for the entire ventilation and warming of the building throughout apparatus and machinery have been fitted up in the basement, under the immediate superintendence of Mr. Watson of Halifax. Mr. J Westmoreland of Islington is the sole contractor, and the building has been erected by him, assisted by tradesmen who have taken contracts from him in the several departments. The new premises are calculated to accommodate 700 children, which, the capacity of the existing building, will contain shelter and education for an aggregate number of about 1,900.

Kirkdale site, 1908.

In 1904, the school was closed and the site became Kirkdale Homes for the aged and infirm. Part of the premises were also used to house children suffering from ophthalmia, who had previously been accommodated in an old house at Olive Mount (see below) until cottage homes were built there.

Following an inspection of the establishment in around 1908, a report noted that:

The administration of the "Ophthalmic" School, which contained some thirty children, seemed to us defective in Cheerfulness, and so far as we saw it, the education given was poor.

The Kirkdale Homes was taken over by West Derby Union in 1922 and then by Liverpool City Council in 1929. In 1948 it became jointly run by Liverpool City Council and the Regional Hospital Board. It changed its name to Westminster House Home for Elderly People in the early 1950s and finally closed in March 1968. The buildings have now been demolished.

Dingle Mount Asylum

By 1872, the Select Vestry had established an isntitution at Dingle Mount for the treatment of female imbeciles, epileptics and lunatics.

Maghull Convalescent Home

In 1878, the Select Vestry opened a convalescent home for workhouse children at Moss Side House, Park Lane, Maghull. A report in 1910 noted that it was then a convalescent home for boys sent there from the workhouse infirmary. About half of the boys slept in tents and preferred to do so.

Fulwood Lodge, Aigburth

In 1886, the Select Vestry began renting Fulwood Lodge, at Aigburth Drive, Aigburth, for the accommodation of infant children from the workhouse.

Mitford House

By 1900, Mitford House, Mitford Street, off Netherfield Road, was being used to house aged women.

Olive Mount Cottage Homes

In 1900-03, the Select Vestry erected cottage homes for pauper children at Wavertree. The site, on Mill Lane, already contained an old house called Olive Mount and its lodge. The house was extended and probably became the administrative centre. Sixteen cottage homes were erected, together with two schools and a superintendent's house. Infants' blocks in an X formation were later added to the north of the site.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes site, 1925.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes aerial view from the south-west.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes from the east (main house at far left), 1925.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes from the south-west.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes infants' blocks, 1925.

Liverpool Olive Mount children's houses from the west, c.1906.

Liverpool Olive Mount girls performing a playground stick drill, c.1906.

A report published in 1909 (although written several years earlier) noted:

These homes have only been started during the last three years, and now all children (healthy) are sent up to this establishment.

Ins and Outs Department.—Here the children are sent up daily from the workhouse and are kept for a period till it is decided which institution they shall be sent to. The Protestants are drafted into the cottage homes, and the Catholics to the various Institutions they are suitable for. There is no "pauper" help: the assistants are responsible for the children under their charge.

The Cottages.—Each cottage can accommodate fourteen children, and the "Foster Mother" in charge has the help of a half timer to assist her with work. She is expected to make all do some little thing, and make the life as homelike as possible.

There are separate cottages for boys and girls and one for babies, the very young children, who require more individual care ; here the "mother" has an assistant, as the children need attention and can give no help.

The Committee hope and believe that the cottage home life will assist the children in training them for work and that girls who have taken share in work of their own cottage, will have received good training for service.

The Governor lives in one of the cottages, and matron in the Ins-and-Outs Block. The matron is responsible to the governor for supervision of all the domestic work, and visits daily each cottage.

The site later became Olive Mount Children's Hospital. Most of the buildings were demolished in 1992-3 but the main house, superintendent's house, and remains of the entrance lodge survive as part of the North Mersey Community NHS Trust Headquarters on Old Mill Lane.

Liverpool Olive Mount main house from the south, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham

Liverpool Olive Mount superintendent's house from the south, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham

Liverpool Olive Mount homes entrance and lodge from the west, 2009.

© Peter Higginbotham

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes snow-clearing at homes entrance, c.1906.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes infants c.1908.

Liverpool Olive Mount cottage homes older children in fancy dress, c.1908.

Highfield Infirmary/Sanatorium (Broadgreen Hospital)

In 1903, the Liverpool Select Vestry opened Highfield Infirmary at Old Swan. It was used for aged and infirm paupers.

Highfield Infirmary site, 1908.

Highfield Hospital administration block, c.1916.

A report on a visit to the establishment in about 1906 described it as:

A large newly-built infirmary, consisting of eight separate parallel one-storied blocks for the aged and infirm paupers from Liverpool.

There is one female phthisical ward, but no windows were open and only one ventilator. Apart from this the accommodation and administration seemed excellent, however.

It occurred to us that separate institution on this scale out in the country might he more suitable for curable than chronic oases, especially as it appeared that the distance from the town placed obstacles in the way of visitors to inmates.

The doctor suggested the need for a more precise demarcation between his own duties and those of the matron.

One of the old women was observed making shrouds; a hardly desirable occupation.

The site seemed damp and the surrounding land uncultivated; but the institution has only been open a short time, and this may probably be remedied

A separate nurses' home stood at the east of the main complex.

Highfield Hospital nurses' home, c.1916.

During the First World War, Highfield was deployed as a military hospital.

Highfield Hospital nursing staff, c.1916.

Highfield House

At around the same time as the Highfield infirmary was built, the Select Vestry established a temporary residence for between sixty and seventy epileptics in an adjacent property, Highfield House, whose entrance lay on Prescot Road.

In 1922, the Infirmary was transferred to the Liverpool Corporation and became the Highfield Sanatorium, treating tuberculosis sufferers. In 1929, it was renamed Broadgreen Sanatorium and later became Broadgreen Hospital.

Heswall Sanatorium (Cleaver Hospital)

In 1901-2, Liverpool Parish, West Derby Union, and Toxteth Park Township jointly established a sanatorium at Heswall for the treatment of phthisis, or tuberculosis of the lungs, in children. Heswall was the first such separate-site sanatorium to be set up by poor law authorities outside London. Situated at the west side of Oldfield Road, the main building was a "half-butterfly" layout, with verandahs facing to the south to maximise their exposure to the sun. The site, overlooking the Dee estuary, had large gardens with seats and a shelter for convalescing patients. The site layout is shown on the 1912 map below.

Heswall Sanatorium site, 1912.

Heswall Sanatorium later became the Cleaver Sanatorium, subsequently renamed Cleaver Hospital.

North End Sailors' Home

In 1887, at a cost of £300 a year, the Select Vestry began renting the premises of the former North End Sailors' Home, on Luton Street, Liverpool, to provide overflow workhouse accommodation for aged paupers.

North End Sailors' Home, Liverpool.

A report on a visit to the establishment in about 1906 described it as follows:

The [North End Sailors'] Home seemed to us defective in every particular. It is rented by the Union, and used as an overflow house for the aged inmates from [the workhouse]. The rooms were low, ill-lighted and hopelessly overcrowded. The men were in many cases lounging in the bedrooms, there being no chairs except in the dining-hall, and there was a total absence of books or newspapers — as far as we saw — and it is impossible to conceive more dismal and hopeless asylum for age. The administration consists of but two officers for 268 inmates. The officer in charge, however, stated that they had no difficulty in enforcing such discipline as was necessary. The only out door space available for the inmates, was an asphalted roof-yard some 35 feet by 25 feet, up so many flights of stairs that, a large proportion of the inmates were unable to mount to it.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

Liverpool Record Office and Local History Service, Central Library, William Brown Street, Liverpool L3 8EW.

- Guardians' minutes (1852-1922)

- Brownlow Workhouse — Admissions (1869-1925); Births (1841-1914); Baptisms (1831-58, 1874-1928); Deaths (1914-24); Creed register (1841-1928); etc.

- Kirkdale Industrial School— Admissions and discharges (1862-1965); Classification registers (1845-97); Creed register (1869-1904).

- Kirkdale Homes — Creed registers (1913-1969); Registers of deaths (1924-1971).

Bibliography

- Liverpool Workhouse Records Collection by I Taylor, Liverpool FHS, 2, 1, Spring 1978.

Links

- The Vestry's early correspondence with the central poor-law authorities is online on the TNA website .

- The 19th Century Poor Law in Liverpool by Mike Royden.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.