The City of London Poor Law Union and Workhouse

Up to 1834

The pre-1834 operation of the poor law and workhouses in the City of London is described in two separate pages on:

After 1834

In setting up a new poor law union to cover the City, the Poor Law Commissioners initially planned to create a single body comprising 108 parishes. Many of parishes within the old City walls were tiny and, by 1834, none was operating a workhouse. However, some of the City's parishes outside the walls had ample workhouse accommodation which could serve the new union. To keep the size of the union's Board of Guardian within reason, the Commissioners sought parliamentary approval for a scheme to depart for the normal system of each parish electing one or more Guardians. This did not materialise, however. Some of the parishes were also found to be operating under local Acts of parliament which exempted them from the 1834 Poor Amendment Act. As a result, the Commissioners set up three unions: the City of London union (which included 96 parishes inside the city walls and two outside); the East London union (with four parishes); the West London union (seven parishes).

The City of London union formally came into being on 30th March 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 101 in number, representing its 98 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

St. Alban's, Wood Street; All Hallows, Barking; All Hallows, Bread Street; All Hallows, the Great; All Hallows, Honey Lane; All Hallows, the Less; All Hallows, Lombard Street; All Hallows, London Wall; All Hallows, Staining; Christchurch, Newgate Street (2); Holy Trinity, the Less; St. Alphage, Sion College; St. Andrew by the Wardrobe; St. Andrew Hubbard; St. Andrew Undershaft; St. Anne, Blackfriars (2); St. Anne and St. Agnes within, Aldersgate; St. Antholin; St. Augustine; St. Bartholomew by the Royal Exchange; St. Benet, Fink; St. Benet, Gracechurch; St. Benet, Paul's Wharf; St. Benet, Sherehog; St. Botolph, Billingsgate; St. Botolph without Billingsgate; St. Christopher-le-Stock; St. Clement, Eastcheap; St. Dionis Backchurch; St. Dunstan in the East; St. Edmund the King; St. Ethelburga; St. Faith the Virgin under St. Paul's; St. Gabriel, Fenchurch Street; St. George, Botolph Lane; St. Gregory by St. Paul's; St. Helen, Bishopsgate; St. James, Duke's Place; St. James, Garlickhithe; St. John Baptist, Walbrook; St. John Evangelist; St. John Zachary; St. Katherine, Coleman; St. Katherine Cree Church; St. Lawrence, Jewry; St. Lawrence, Pountney; St. Leonard, Eastcheap; St. Leonard, Foster Lane; St. Magnus; St. Margaret, Lothbury; St. Margaret, Moses; St. Margaret, New Fish Street; St. Margaret Pattens; St. Martin's, Ludgate; St. Martin's Orgars; St. Martin Outwich; St. Martin Pomroy, Ironmonger Lane; St. Martin's, Vintry; St. Mary Abchurch; St. Mary Aldermanbury; St. Mary Aldermary; St. Mary-at-Hill; St. Mary Bothaw, Dowgate; St. Mary-le-Bow; St. Mary Colechurch; St. Mary Magdalen, Milk Street; St. Mary Magdalen, Old Fish Street; St. Mary Mounthaw; St. Mary Somerset; St. Mary Staining; St. Mary Woolchurchhaw; St. Mary Woolnoth; St. Matthew, Friday Street; St. Michael, Bassishaw; St. Michael, Cornhill; St. Michael, Crooked Lane; St. Michael, Queenhithe; St. Michael-le-Quern; St. Michael, Paternoster Royal; St. Michael, Wood Street; St. Mildred, Bread Street; St. Mildred the Virgin, Poultry; St. Nicholas Acons; St. Nicholas, Cole Abbey; St. Nicholas Olave; St. Olave, Hart Street; St. Olave, Old Jewry; St. Olave, Silver Street; St. Pancras, Soper Lane; St. Peter, Cornhill; St. Peter, near Paul's Wharf; St. Peter-le-Poor, Broad Street; St. Peter, West Cheap; St. Stephen, Coleman Street (2); St. Stephen, Walbrook; St. Swithen, London Stone; St. Thomas the Apostle; St. Vedast, alias Foster; Whitefriars Precinct.

Later Additions (from 1869):Barnard's Inn; Bridewell Precinct; St. Andrew, Holborn; St. Bartholomew the Great; St. Bartholomew the Less; St. Botolph Aldersgate; St. Botolph without, Aldersgate; St. Botolph without, Aldgate; St. Bride; St. Dunstan in the West; St. Giles without, Cripplegate; St. Sepulchre; Serjeant's Inn; Thavie's Inn.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 57,100 — ranging from St. Christopher-le-Stock (population 72) to St. Stephen, Coleman Street (4,014). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-6 had been £59,941 or £1.1s.0d. per head of the population.

The City of London was a wealthy union and was initially extremely reluctant to build a workhouse. Most of its paupers received outdoor relief, largely in cash, supplemented by generous allowances of food and drink. Its indoor paupers were farmed out, at great expense, in accommodation run by private contractors located miles away from the union's offices at the Mansion House. Children were placed at Mr Aubin's school at Norwood, women went to a Edward Deacon's establishment at Stepney Green, and able-bodied males were sent to Marlborough House on Peckham High Street, run by William Richards.

Conditions at Peckham were the subject of regular complaint. In December 1838, the Lord Mayor visited the establishment after receiving a petition from 176 of the inmates. Although he found the premises in an excellent state of cleanliness, the inmates appeared to be receiving less than their regulation allowance of bread. They also complained of overcrowding and being only allowed out once a month.

Marlborough House was also used for casuals, numbering up to 300 a night, which was just enough in summer but wholly inadequate in winter. In January 1841, more than a thousand casuals besieged it every night, and were crammed three to a bed in temporary wooden huts. As well as the overcrowding problem, the casuals also were often unruly and assaults on staff were not uncommon. Despite its distance from the City, Peckham was particularly popular with casuals. When space permitted, they were allowed to stay for several nights in a row and, unlike other workhouses, no work was required in return for their board. The union tried to persuade vagrants to go elsewhere by offering them bread and money instead of shelter. Eventually, after a long battle with the Poor Law Commissioners, the union gave way and agreed to build its own workhouse.

The Bow Road Workhouse

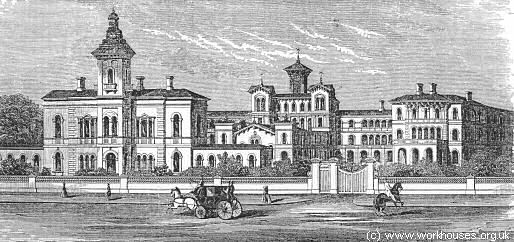

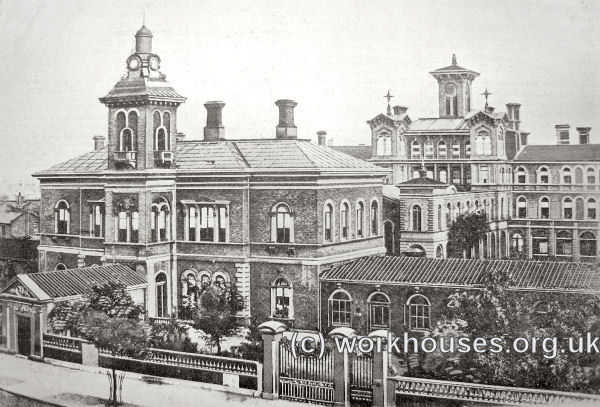

Eventually, the union agreed to build its own workhouse on Bow Road. The new premises, housing up to 800 inmates, opened in December 1849. The palatial design by Richard Tress cost over £55,000 to construct and boasted central heating, a dining-hall measuring 100 feet by 50 feet, Siberian marble pillars, and a chapel with stained glass windows and a new organ. However, the new workhouse had room only for those casual applicants deemed sick and helpless — healthy ones would be refused admittance.

The location and layout of the workhouse are shown on the 1870 map below.

City of London Workhouse Site, 1870

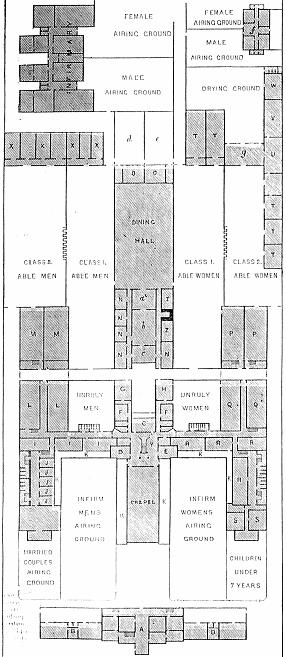

The architect's proposed design and the workhouse layout are shown below.

City of London workhouse, 1849 (architect's impression).

City of London workhouse plan, 1849.

Key to City of London workhouse plan, 1849.

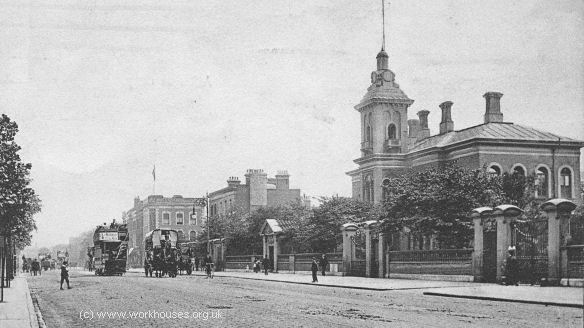

City of London workhouse from the north-west, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

City of London workhouse from the north-east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

City of London workhouse from the north-west, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The entrance block was at the north of the site facing onto Bow Road. It contained the porter's lodge and receiving wards for new inmates.

City of London entrance block from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

City of London entrance block from the north-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The main building was H-shaped with males accommodated on the east side, and females on the west. Chapel and dining-room blocks were located at the front and rear centre of the main building.

City of London rear of entrance block from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

City of London main building from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

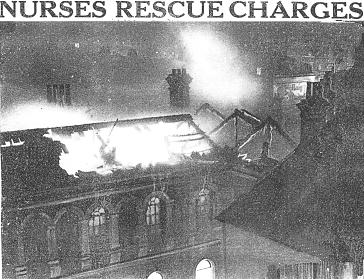

The west wing of the main building was destroyed by a fire in January 1935.

City of London main building from the north-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

City of London fire report, 1935.

A large infirmary block was situated at the south-east of the site.

City of London infirmary block from the east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1869, the City of London Union, the East London Union, and the West London Union were amalgamated to form an enlarged City of London Union. The new union took over the former East London Union workhouse at Homerton, and the former West London Union workhouse on Cornwallis Road in Upper Holloway. The Bow Road site became the union's infirmary.

In 1909, the Bow Road was vacated by the City of London Union who had decided to concentrate their work at Homerton in the former East London Union workhouse which had just been substantially enlarged.

Homerton workhouse site, 1913

After a period of standing empty, the Bow Road building was re-opened on 1st March 1912 as Bow Institution. Although still managed by the City of London Board of Guardians, it now provided medical and nursing care for workhouse inmates from other unions. By October 1912, nearly 300 paupers from the Poplar Union were in residence, including many who had previously been in Poplar's Forest Gate branch workhouse. The Bow Institution was later renamed the City of London Institution, then in May 1936 it became St. Clement's Hospital which it is still known as today.

In March 1897, the City of London Union Guardians became involved in a scandal over the refreshments that were served at their board meetings. One of the board members, Mr John Lobb, proposed an innocuous sounding motion 'that the Dining by the Guardians at the workhouse at Homerton and the infirmary at Bow after the business... be discontinued.' Press reports subsequently revealed that the Board's meetings were conducted in a manner worthy of the pages of Oliver Twist. Proceedings began with a light luncheon of bread and cheese, beer, spirits etc. After the main business of the meeting, typically an hour to an hour and a half later, the Guardians were served a repast of fish (salmon for preference), fowl, roast mutton and beef, and sundry other dishes followed by a selection of puddings and sweets. The food was accompanied by champagne and other wines as well as spirits. Then came the important matter of a long series of well-lubricated toasts to the Queen and Royal family, the Chairman of the Board, the Vice Chairman of the Board, the Chairman for the day, the Vice Chairman for the Day, and so on, finally concluding with a toast for the Oldest Guardian and one for the Youngest Guardian. Finally, the members rounded off their meal with tea, coffee, biscuits, cakes, and other dainties and delicacies. As well as the unseemliness of such consumption and cork-popping taking place in earshot of the workhouse inmates, concerns were raised over the financing of such feasts and whether they were being subsidized by the rate-payers. Mr Lobb's motion, needless to say, was defeated.

In 1900, an unusual story concerning the Homerton workhouse appeared in the press.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 42 Clifden Road, Clapton.

In 1909, the Bow Road site was vacated by the City of London Union, who had decided to concentrate their work at Homerton. After a period of standing empty, the premises were reopened on 1 March 1912 as Bow Institution. Although still managed by the City of London Board of Guardians, it now provided medical and nursing care for workhouse inmates from other unions. By October 1912, nearly 300 paupers from the Poplar Union were in residence, including many who had previously been in Poplar's Forest Gate branch workhouse. Subsequently renamed the City of London Institution, the west wing of the main building was destroyed by a fire in January 1935. The following year, it became St Clement's Hospital, which continued in operation until 2005.

In recent years, the buildings have been redeveloped for a mixture of community, cultural, commercial and residential use.

Thavies Inn Casual Ward

By 1871, The City of London had a casual ward located at Robin Hood Court, at the south end of Thavies Inn, Holborn. Its location is shown on the 1873 map below.

Thavies Inn casual ward site, 1873.

Staff

- 1881 Census — Cornwallis Road workhouse

- 1881 Census — Homerton workhouse

- 1881 Census — Thavies Inn Casual Ward

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1881 Census — Cornwallis Road workhouse

- 1881 Census — Homerton workhouse

- 1881 Census — Thavies Inn Casual Ward

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- Guardians' minutes 1837-1930).

- Bow Road Workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1889-1910), Deaths (1866-74).

- Bow Road Infirmary: Admissions and discharges (1889-1910), Deaths (1866-74).

- Homerton Workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1857-1902), Births (1865-1905), Deaths (1865-1908), Creed register (1876-1911).

- Lower Clapton Workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1911-22), Births (1914-25), Deaths (1914-15), Creed register (1914-33).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Tanner, Andrea (1995) The City of London Poor Law Union, 1837-1868 (PhD thesis, Birkbeck College, University of London)

- Tanner, Andrea (1998) A Turbulent Priest - the chaplain of the City of London workhouse by Andrea Tanner (London Journal no. XXIII)

- Tanner, Andrea (1999) The Casual Poor and the City of London Poor Law Union, 1837-1869 by Andrea Tanner (Historical Journal, 42, no. 1)

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.