James Greenwood at Islington Workhouse Casual Ward, 1906.

In 1906, forty years after his famous undercover exposé of conditions in the Lambeth workhouse casual ward, James Greenwood was commissioned by The Tribune newspapers to repeast his adventure in a visit to the Islington casual ward. Here is the first instalment of his account (link to next instalment at end):

AFTER 40 YEARS.

———

THE AMATEUR CASUAL OF 1906.

———

By JAMES GREENWOOD.

(The "Amateur Casual" of 1866.)

When the Editor of The Tribune asked me to repeat the investigations which I made forty years ago, and to spend another night in a casual ward, I was not particularly eager to undertake the commission.

I could not ignore the fact that it was a matter demanding some consideration before I pledged myself to it. True, I had once before essayed the bold adventure, commenting on which the "Times," in a leading article ("A Night in a Workhouse" was reprinted from the "Pall Mall Gazette" in three separate issues of that newspaper), remarked of the writer that, like Dante, he must find himself pointed at in the streets as "the man, who had seen hell," at the same time expressing the flattering opinion that many a Victoria Cross had been bestowed for less daring, as well as for service of vastly less utility and merit." I suppose, however, since nothing came of it, that her Gracious Majesty's advisers ignored the handsome suggestion.

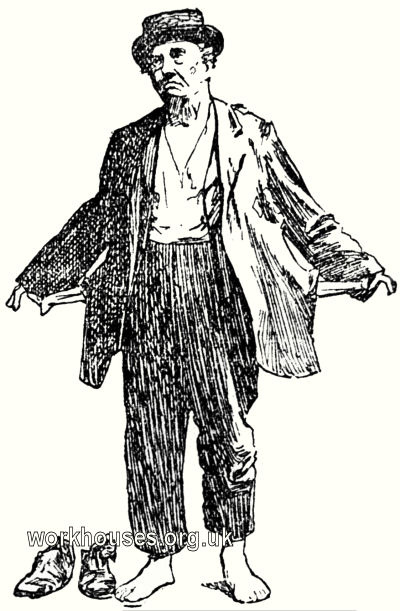

MR. JAMES GREENWOOD.

It is a long time ago, and until now I have not dealt with the subject since; but there are features Of that unique experience I can recall as vividly as though they were no longer than a month gone by. It was appalling to lie in that dreadful shed from nine o'clock at night until first glimpse of winter daylight next morning and witness the terrible spectacle of at least a score of those who could undeniably claim to be one's fellow creatures — able men, old men, and mere lads — indulging for their amusement in almost every conceivable sort of devilry calculated to annoy and torment the decent few who were their fellow-lodgers. At one time competing among themselves as to who could invent the most obscene and blasphemous utterances, at another singing songs that might have won applause from the everlastingly doomed of the bottomless pit, or, by way of variety cursing and deriding those who were goaded to rebuke and remonstrance. And all this as we lay, the villainous and the victims, on our dirty hay-bag beds, with scarce a yard of space between, on the cold stone floor and in the dark, save for a single feeble jet of gas.

THEN AND NOW.

It is true I emerged unharmed from that and many other kindred troubles, but that was two score years ago, and when my age was only three-and-thirty, and 1 was hale and hearty, and I think I may say mettlesome as well, and able to hold my own tolerably well in a scrimmage. It was different with me now, with my three score and thirteen years to answer for. But then, as I argued with myself (being really not averse to the job), it would be an undertaking one might engage in with far less risk than in the good old times. Modern enlightenment and increasing regards for the dictates of Christian charity had probably much improved the accommodation provided for those who were brought so low as to be compelled to seek workhouse shelter for the night, and as far as I was personally affected, to play again the part of amateur casual would involve me in little worse to bear with than to "dress for the occasion," and just for one night sleep on straw instead of feathers, with a workhouse breakfast of bread and skilly that I might eat or leave as I felt disposed, and with a few hours of rough hard work to do before freedom was restored to me. So, to prevent further consideration inducing me to alter my mind, I communicated at once with the editor to the effect that he might book me for the proposed job. And no sooner was the matter thus far settled than I made a perplexing discovery!

A MAN OF KNOWLEDGE.

I was altogether in ignorance of the fact that within the past few years an alteration affecting the whole of the metropolitan casual wards had been in operation, and that the present law was that the recipient of casual relief, instead of being detained not longer than fourteen or fifteen hours, as in the old time, he was under the new rules not released until forty hours had expired. I obtained this item of information from a strong and able-bodied ruffian who was waiting for admission at Whitechapel Workhouse, while in my proper attire I was reconnoitring in the vicinity, and who followed me up the street begging. He was, he told me, that "holler" for want of food he could hear his heart beating in his inside "like a drum." I offered, if he accompanied me as far as the first shop available for the purpose, to buy him something to eat; but he came to a halt at the first public-house instead, and remarked that if it made no difference to me, perhaps in his weak state a drop of rum would do him more than wittles, and it was while drinking it (neat) that he enlightened me. "Forty hours is the time you are kep', sir." "But you are well cared for all the time! It isn't like it used to be!" to which, with a sour grin, he made answer: "Oh, no! It's just lovely now. Like the Kingdom of Heaven — spelt back'ards."

And he then proceeded to relate a few details illustrative of the loveliness of the treatment of casual paupers under the present system, and which — assuming that they were founded on fact — might well set me seriously reflecting whether I was not pledged to an enterprise that might hasten my conveyance to Highgate Cemetery. Further preliminary inquiry would, at all events, be Judicious, and being on friendly terms with certain officials at Camberwell Workhouse — of course, concealing my purpose — the personal investigation I was courteously permitted to make there and then went far towards corroborating my Whitechapel friend's account of the "lovely place" a modern casual ward was. And it was all the more impressive because I was assured that it was precisely the same at all the twenty-eight casual receptacles with which the metropolis is now provided, the whole number being under one control, which was Governmental, and quite apart from ordinary workhouse rule.

A GLOOMY PROSPECT.

The discoveries I made at Camberwell were not encouraging as regards my secret design. It was revealed to me (in the evidence of my own eye-witnessing that as an "up-to-date" casual a couple of gloomy cells — one within the other — would be placed at my disposal. That one — its length and breadth being about nine feet by five, with something in the nature of a skylight in its low roof — was my bedchamber. A two-foot plank hinged against the wall when out of use served, when propped up by two iron legs, as my bedstead, on which, by way of bed, was spread a bag of loose hay.

The possession of this would be given me, along with a couple of rugs and a night-shirt, after I had undergone the ordeal of the bath and deposited the whole of my wearing apparel in the bathroom till getting-up time next morning, when it would be restored to me, and my bed removed. The "bunk" it had rested on would serve me at once as a seat and a table, while, still in dismal seclusion, I ate my bread and swallowed my ration of skilly. In opening the door at the end of the first solitary cell I should find another of the same dimensions, to which daylight of a sort was admitted through an iron grating. This was my workshop, where I had to perform my day's task at stone-breaking or wood-sawing or oakum-picking, with an hour's rest for the mid-day meal, consisting of a "chunk" of bread and three ounces of cheese, and which said hour I was at liberty to spend in the front cell, instead of the back, by way of a change, but all alone and in silence. Then back to my grated dungeon and the saw or the hammer till supper-time and more bread and skilly, and yet another night of plank and hay-bag, and another meal of bread and the dreadful oatmeal concoction, and a little more hard labour, until my forty hours were accounted for, and I was free to depart. Such was the woeful knowledge I gleaned at Camberwell as to what "a night in a workhouse" now meant, no matter the metropolitan parish applied to.

IN RAGS AND TATTERS.

But, after all, it was not so very much to endure in comparison with the old-time horrors of the parochial asylum at Lambeth, and, nothing daunted, within a week, anybody who suspected my intent (which, happily, nobody did) might have observed my picturesque figure slinking through the back streets of Upper Holloway at dusk of evening, my destination being the casual ward of Islington Workhouse.

"This wicket-push," says the notice to casual applicants, inscribed on the highly-respectable great gate by which those seeking night-shelter at Islington Workhouse enter — "This wicket-push is open from four until six o'clock every evening. After that time casuals must inquire at the office."

The "push" is a little door opening in the larger one. Being, as I thought, in good time — it wanted a quarter to six — I tried the entry in question, but found it fast. Resolving to try again presently, I walked up the dark street and was standing by a lamp-post with my hands buried in the pockets of my dilapidated, buttoned-up jacket, when up came the lamp-lighter. "We shall have a sharp frost to-night," he remarked sympathetically to me, seemingly noting the scantily-clad vagabond I appeared, and probably divining my intent, "warmer inside than out, anyway." It was not a comforting prognostication, reminding me, as it instantly did, of an icy night full forty years ago when I was pledged to an adventure exactly similar to that I was then engaged in. "It has got to be done, however," I said to myself with a shrug of my shrinking shoulders. "I will have another try at the 'push.' "But. I was no more successful than at first, and glancing towards the distant office saw a liveried official standing at the door, and made humble approach to him.

HOSPITALITY UP-TO-DATE.

It could not be said that he was a man of hospitable mien. On the contrary, his manner was austere and resentful, and I had got no farther than "I beg your pardon, sir," when he broke in with, "Well! What do you want? Come inside. I can't talk to you in the street."

I had no desire that he should do so, and meekly followed him into his office, where there was a desk, behind which he took his stand. He asked for my name, which demand I fictitiously evaded, and the same when he inquired what I did for a living. My replies being entered in a book, his next question was, Where are you from?" Not caring to implicate Fleet-street, I hesitated, and he repeated this question, this time fiercely. I told him Woolwich, adding, apologetically, "I did not quite know what you meant, sir." "Yes, you did," he snapped at me. "Why didn't you tell me the truth at first? Take off your boots and stockings!"

Not feeling sure as to whether this was intended as a punishment for my assumed prevarication, or whether it denoted simply that my wish for admission was acceded to, which might dispense for the present with the articles in question, I did not instantly comply with the command, but he presently repeated it in such an angry tone of voice that I set about the job without further delay, and in a minute or two afterwards stood barefoot in the awful presence, wondering what was next. But I was speedily enlightened. "Take out everything you have in your pockets, and put the things on that bench. Turn your pockets inside out, take that comforter thing off your neck, loose your shirt-collar, and unbutton your waistcoat." And seeing that these orders were imperative and must be obeyed, I did as I was told. "And now," queried the austere officer, "where are you going when you are discharged from here?"

MR. JAMES GREENWOOD AS "THE AMATEUR CASUAL."

This seemed to give me an opportunity for making my first move in an artful plan I had concocted, and the object of which was to restrict my durance to a single night and part of the day following, instead of remaining there the full time by law insisted on, viz., forty hours. "I've got a letter here, sir, if you will be so kind as to look at it. There is a person living at stoke Newington who wrote to me by post to tell me of a job he could find me to do if I called on him tomorrow afternoon — —"

"Which you won't do," he interrupted me, at the same time scornfully rejecting the letter I was offering him. You'll be here all day to-morrow and part of next day as well, and that you know as well as I do." And dismissing me with a wave of his hand, a subordinate appeared and beckoned me to come that way. And with my loose trifling belongings tied up in my blue bird's-eye cotton pocket-handkerchief, and my boots with the socks tucked into them in my hands, I responded to the summons.

(Transcription by Peter Higginbotham, 2023.)

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.