A Real Casual on Casual Wards - Mile End (1866).

In March 1866, J.C. Parkinson published an article in the Temple Bar magazine which included accounts by a 'real casual' of his experiences in the casual wards of around a dozen London workhouses.

Here is the report on the Mile End casual ward.

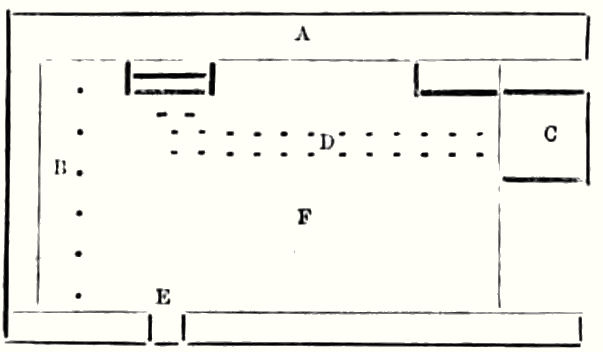

The next place we will call in at will be Mile End Workhouse. The houseless poor are taken in at six o'clock here, and very punctual they are too. The porter (a paid official) ranges the casuals in a long row up a passage, and they put their heads in at a door, where he sits comfortably before a fire, and answer the usual questions. The porter is a sturdy sort of man with a large nose, who will be obeyed. We go after this into a yard and turn round sharply to the left through a door; at the entrance stands an old pauper, who is guardian of the place, and bathes you. A most crusty old man too. Soon as all are through the door we find it is a yard — perfectly open — and that we have to undress in this yard. In order that you may perfectly understand this affair, which is infamous, I will draw you a diagram of the yard, &c.:—

A is the casual ward; B is a shed open at the front, covered with wood, with a seat against the wall to sit on and put their clothes on, and under the seat; C is the bathhouse; D is the walk from which you come out of the bath-house (C) to the casual ward (A); E is the door in which you enter the yard; F is the yard.

As soon as we got into the yard the porter told us to undress under the shed (B). Some of the casuals thought nothing about this, as they immediately began to do it, but some others loudly demurred to it, and cursed until they were nearly black in the face. One man was especially wroth, and threatened to strike the old pauper who had said it was quite good enough for such "[blank] thieves" as him. The old pauper further told him that the guardians had seen it too, and very highly commended it, and if any [blank] casual who came here didn't like it, he could go out." That was it. Yes, that was it; but as I determined to see it out, I settled down to see it all. After a good deal of cursing the clothes were stowed away, under or on the top of the seat in the shed, which is perfectly open facing the bath-house, and we stood there naked waiting for our turn to be bathed, huddled up on a cold January night of the present year, shivering.

When it came to my turn I went across the yard — how the cold flags did make my feet ache! — and jumped into the bath (about twenty had been bathed in the same water before I got in). The bath was very warm, and quite a contrast to the cold in the yard, but, oh horror! when I got out of the bath I thought some of my teeth would have fallen out. I was shoved out into the yard, with the sky over my head, to wipe myself as well as I could with a wet towel. The bath was so small that we were obliged to go into the yard to make room for others. After wiping myself a rough canvas shirt was put into my hands, and in the yard I put it on and ran into bed, or into the casual ward, and then to bed. I shan't soon forget that night. How I did fume in bed for a sheet of note-paper that I might let some of the rascally guardians know my mind; What cursing by everybody! One well-seasoned casual in the next bunk to me did nothing but laugh, and asked me bow I should like it "in snowy weather?" I put the question to him, "Is it always so?" Yes, it was; frost and snow, fine or fair, always the same. The beds are identical with Lambeth, so I need say nothing about them. In a very few minutes the skilly and bread were brought; the former in a "pannikin." Having finished this, the men (pauper officials: the paid porter had never been once to see us) left us, locked the door, and we saw no more of them until morning. At about seven o'clock we were aroused, and each had to go out into the yard in our shirts and hunt (no better word) for our clothes amidst the many bundles of old rags. I was especially desirous to go out early, as I had left a hat out, and I know from experience that if some of the casuals could get a chance, it would be made all the worse. I was not quick enough, however; some rascally fellow had nearly beaten the crown in. We were generously allowed to take our clothes into the casual ward and put them on, after that the ward was locked up, and we got our breakfast standing in the yard in the cold. This time the porter was standing by. After that he picked six of us out — me among the rest — to do some work; the others were kept picking oakum in the yard. We followed him to a shed where a lot of pauper inmates were doing various things in the making of bundles of firewood I have seen hawked about London — some tying them up, others chopping pieces into smaller slips, and one or two sawing at a circular saw. At this last we had to turn a wheel, around which a strap was placed, which turned the saw. We took it in turns, three at a time, and had finished about half-past nine o'clock. Some of the old paupers were very kind to us; one, especially, approaching me, gave me a large lump of bread, which he did with a very patronizing air, saying, "Here; we don't know what we may have to come to ourselves yet!" A pauper inmate speaking thus to a casual pauper! We got out of Mile-End Workhouse, however, at last, and heartily glad I was.

(Transcription by Peter Higginbotham, 2023.)

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.