Julia Varley - Life in the Casual Ward

This is Part 1 of Life in the Casual Ward, an account of undercover visits in 1904 to workhouse casual wards between Leeds and Liverpool by former Bradford Poor Law Guardian Julia Varley.

MISS JULIA VARLEY.

The tramp is ever with us. He has been a much-discussed subject from age to age. At nearly every Poor Law Conference something is said about him, and all sorts of proposals are made for his treatment. Social reformers wrestle with him in vain. He remains "on the road," and nobody knows how to get him off it, and how to make him a useful and decent member of the community. I was lately tempted to enter a few casual wards so that I might see the women occupants as they are, and perhaps get material that would enable me to make suggestions for dealing with these wanderers from Union to Union. In a few short articles I propose to put before my readers the daily round in some of the casual Wards: in Yorkshire and Lancashire. I will narrate in a simple way my life as a tramp, and at the close sum up my experiences and give my ideas on the treatment of tramps. I set out from Bradford with an open mind, prepared to learn the lessons taught by daily contact with the "flotsam and jetsam" of life. My experiences as a Guardian had dispelled a lot of amateurish sentiment, and my intimate knowledge of the average working I woman gave me sufficient sympathy to judge fairly, I hope, so for a while I left friends and borne behind, and stepped down into the depths of the submerged tenth.

I GOT AN OLD DRESS AND JACKET

and sailor hat, with a change of old linen in a small bag and three halfpence in my pocket, and set off on my first journey as a "casual." Leaving Bradford about four o'clock on a Thursday afternoon I walked to Leeds, and arrived tired about seven o'clock. When I made enquiries as to the whereabouts of the Workhouse I found that I had a mile and a half further to go, so I stepped out rather briskly, and landed at the doors at 7.30. The casual wards have been quite recently opened, and show an imposing front, with separate entrances for males and females. I went up the steps with a fluttering heart and courage almost gone, and found myself in a small room with seats. An electric button bore the word "Push." and I obeyed the command, and presently heard the sound of a key in the lock. A door opened, and an attendant in uniform said, "Well," and I asked for a night's shelter. "What's your name?" I gave her my new name, in a voice that seemed to me terribly weak, and giving me a good stare she said, "I know you; you have been here before and belong to this city." I told her she was mistaken, as I had not been there before, and was not an inhabitant. (She had seen me before, and under totally different circumstances. I recognised her as soon as she entered the room.) I was awfully tired, and had sat down, and she said rather sharply, "Stand up." I did so, and answered the rest of her questions, "Age, where come from, and destination," and I am not quite sure whether she meant nationality or religion when she said, "Church of England?" and I Said "No, Baptist." and she replied, "But you are English." This over, I was told to follow her, and now found myself at the end of a long corridor, where there was a bathroom.

I WAS TOLD TO EMPTY MY POCKETS.

This I did, and handed over my purse with the aforesaid three halfpence, a comb, and a pocket handkerchief. She asked if I had any money, and I told her. She said, "You will get it back for telling." I was told to undress, whilst a pauper prepared the bath. The bath-room was beautifully clean and contained two baths, which could be screened with a mackintosh curtain, two wash bowls, and a sink. The walls were of white-glazed bricks. The water ready, I was told to step out of my clothes and into the bath. I asked the attendant if I might bath myself, and she said, "Have you never been in one of these places before?" and when I said no, she replied, "You may if you promise to wash your head." But the woman was in the bath-room all the time. I was given a clean towel and a nightdress. This I found was not clean, although I believe it is supposed that each casual shall be supplied with a clean one.

This ordeal over, I was led to the bedroom. All the floors are concrete. After a warm bath it is not pleasant to walk with bare feet on cold concrete, but that has to be done. I found three full-sized beds in the room, with two occupied. Three rugs were given me, and I was told to make my bed. This seems to be a simple proceeding. Roll one rug up for a pillow, spread one for a mattress, and cover yourself with the third. This I did at first, not knowing better. My supper was brought me — a pint of gruel and six ounces of dry bread. I was very thirsty, and drank some of my gruel; but it was cold and very salty. One of the women, who was groaning terribly, asked me if I did not eat all my bread to give her some, as she could eat it. She thought she had eating "beatie," as she was always hungry. I gave it all to her, and she had finished it in the morning. By this time I found that I had made some mistake in the bed-making, and I made another attempt. When I explain that they are wire beds, with no mattress or pillow the difficulty I had before me will be better understood.

STANDING WITH BARE FEET ON THE COLD CONCRETE FLOOR,

with a nightdress which might have been longer with advantage as my only attire, I was wondering what to do to get most comfort out of the business when I was startled, by hearing a voice say, "Hey, missis, don't shake all the feathers out of the bed; ye can't make the bed any softer. Fold one rug into four to lie on and roll yourself in the others." I did so, and once more lay down. It was not long before the owner of the voice, who had the command of some of the filthiest language ever invented, started talking. She was an oilcloth hawker, and had started a tour of the tramp-wards to keep out of the way of her husband, who had just come out of prison for "leathering" her, after she had split his bead open with her clog. She was a born hawker. Her mother owns a travelling van and her husband hawks anything. Her "terms of endearment" while speaking about him were blood-curdling. I covered my head and tried to get to sleep but the wires seemed to be boring their way into my flesh, the thick hard rugs pricked and wouldn't fold round one properly, every movement let the cold air in, my head ached with being low, and to crown all come the oaths from one bed and the groans from the other. I was just dropping into an uneasy doze when voices outside the door roused me again. Sharp voices and loud answers seemed to point to a late arrival. This also aroused my companions, and an animated conversation about the ailments of the groaner began.

THEN FOLLOWED TALES OF ESCAPADES

in which men and drinks seemed to have first place. At last they ceased, and again slumber visited us. I awoke several times during the night, with cold and discomfort, and was truly glad whet morning came.

At eight o'clock the pauper who had been about the night before unlocked the door, and brought our breakfast to bed (?) to us — half a pint of gruel and six oz. of bread, which is the regulation allowance for supper and breakfast. Then our clothes were brought and we dressed. The girl who was ill was told that she had to stay in till the doctor had seen her again, while the others prepared to go out. I never thought to meet such a shameless creature, and the half-hour that followed will always, when I think of it, make me feel ashamed that she bore the name of woman. She told us she would beg a copper and then buy some bootlaces and sell them from door to door until evening. Then she would find out what class of men got their wages, and she was going to try to get something from them. At last she took her departure, and the air seemed a little sweeter. I was very sorry for the other girl, who seemed very nice. She had been a servant, but had fallen on bad times, and her companion was not one to help her up, rather the other way. She did not use bad language, and reproved the other when she noticed she did not swear. She was moved into another room, and I was given a brush and told to sweep and wash the cells, ten in number, the corridor, and bath-room, &c. The smell in the cells was almost overpowering; the faint (and in many cases strong) sickly smell of humanity, accompanied by the odour of unwashed clothes, got on my stomach until the tramp master opened the ventilators, and it felt better. I found that all the cells with one exception had been occupied by men, although it was the women's part. This was on account of the crowd of men who came in that night. I had been told an easy way of doing the task set me, and so got on very well with my work. During the morning I came across the woman who came in late the night before. She had a girl of fourteen with her. They had been put in the laundry, and had 24 shirts to wash and dry, and mangle. About 12.30 our dinner was given us, and we had to eat it in the bath-room as there was nowhere else for dining except the cells. Bread and cheese with cold water to wash it down, that was our dinner. I was very much amused at the comments of this woman, for she had no idea she would be forced to stay more than an hour or so after breakfast, and she had been told that there was a decent bed. Her curses were both loud and deep when she discovered the truth. She had never been it a casual ward before, and it was the child who suggested it, as they had no money and it looked like raining. I got her history while we were dining. She was a hawker of smallwares, and the little girl sold lavender packets — She had

BEEN ALL OVER THE COUNTRY,

and had walked from Tadcaster the day before and was bound for Wakefield. This woman had also a great command of language, but she was a clean woman. The good advice she gave me as a beginner on the road showed that. I was told who to avoid and how to shun undesirable companions. The little girl was rather pretty and very simple for her age, and her great love for her mother was a beautiful sight. One naturally says "Poor little soul," and yet she was perfectly happy.

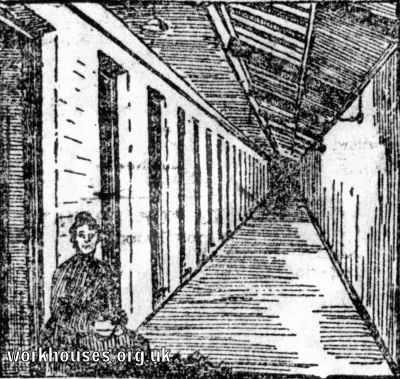

CORRIDOR SHOWING SLEEPING CELLS.

After dinner I had to blacklead the grate that ran the length of the corridor, clean the knobs and taps, and dust all the cots and fold the rugs This last duty got me into trouble The tramp mistress said that anybody with any sense would have managed better than I had done. I told her I was sorry, but I had not served an apprenticeship, and the duty was a new one, but I would do better next, time. This finished our task for the day, and we went to bed. This tickled me immensely, as I have been in the habit of burning the midnight oil; and to go to bed at six o'clock, with the sun shining gloriously, and to such a bed, too, was a very odd experience. During my operations I had managed to confiscate another rug to use for a pillow, I had a splitting headache, and had had an attack of bleeding from the nose. I asked the tramp mistress if she could give me a powder to relieve my headache. She said she had some pills. They did not keep headache powder but she would see the doctor. I have not got that powder yet. Our clothes were taken away and supper served. Gruel again, though I had had more than enough of it. The little girl got tea, and dripping and bread. Her mother shared it between us and they had my bread, while I drank a little of the gruel. Then, again, the same old performance with the beds. it was

MUCH PLEASANTER THAN THE PREVIOUS EVENING.

The child talked us to sleep, then she roused us to watch her do a skirt dance with her nightdress, while her mother grumbled about the place. Then she told fairy tales whose ending was always "something nice to eat" until the shadows lengthened and she fell asleep. Several times in the night I was awakened and heard her saying "Mother, you've left loose of me and I'm. cold." It was fearfully so, and we could not get warm, whilst the wire mattress was torture. Once more morning and breakfast — the same dear old gruel. For the first time since our bath we had a wash and combed our hair. Although we had the run of the bath. room, and could have plenty of water and soap we could make no use of them, as there were no towels. It was tantalising. At last the door was unlocked, and we were free. The beautiful morning air met us like a salutation, and made us feel that the earth was a grand place, even for tramps. We decided to spend my three halfpence in tea. On the way to the town the girl sold two packets of lavender, so that made our capital into threepence halfpenny, and with the dry bread left from our breakfast we found we could go in for a feast. We had three mugs of tea, and 4oz. of potted meat, with the odd halfpenny left for luck. Before we parted they gave me some addressee of "nice lodging houses where there were not many bugs, and every convenience" in case I did not want to leave the place, and then we said good morning. The woman called me back to tell me how to manage to make a living — honest, mind you — by selling lavender. With a ten mile walk before me and no money I finished my first experience of a casual ward.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.