Julia Varley — Life in the Casual Ward

This is Part 3 of Life in the Casual Ward, an account of undercover visits to workhouse casual wards between Leeds and Liverpool by former Poor Law Guardian Julia Varley.

"Over the hill from the poorhouse" was the thought in my mind as I faced the long lonely walk to Rochdale. How to get out of the hills seemed a puzzler; there was no one about. I took a cartroad and walked on, and presently I came across three children, who were going to school, and enquired my way to the village. I found that I had a walk of over two miles to get on the main road, but as the children had to go over a mile, and seemed glad to have company, the walk was very pleasant, down dale and up hill, through shady woods, where a faint blue haze told of the presence of bluebells, and the musical sound of a running brook tempted one to linger. At length I found myself in the main street, and twelve miles from Rochdale. Remembering an address that had been given to me, where I might get helped if I introduced myself, I called and explained my position, but the gentleman had either, been previously "had," or did not mean to be, and I was sent empty away. The next place visited was a newspaper office, and the manager was very polite, and gave me paper and envelope, so that I might send home. I had some paper flowers, but could not muster up sufficient courage to sell them. I called at one house, but when the woman came to the door I asked for a drink instead, so I decided that the best thing would be to push on. Shortly afterwards I found myself under a house whose nameplate told me that it was

THE WEAVERS' UNION OFFICE.

Here, at any rate, I fancied I might have a chance, so rang the bell, and asked for the secretary. This gentleman listened to my tale of woe, then burst into laughter, and I saw that I was "gathered in." After a most interesting conversation on labour representation on public bodies, he invited me to dinner. As I had only a penny in my possession, which would not certainly purchase a three-course dinner, I gladly accepted his invitation. He took me to his home and fed me well, then set me on my way. It was a very pretty walk still down in the valley, with hills on both sides, and threading my way between them, I arrived at the Workhouse just after the tramps were admitted, and made my way to the lodge, where the same old performance took place. I delivered up my basket and purse (contents 1d.), and was put into a room to await the doctor This was the first time this had been done since I started. Here I waited three hours before he came, In the meantime three other women had arrived, and when we rose to meet him we, were as queer a quartet of tramps as one could meet. One, an old woman of nearly 60, I should think, had been on the road for forty years, and I knew all the professional tramps of the day. The second was a sharp, wiry woman of forty, who had a regular round of casual wards and lodging houses, and the third was a queer specimen of humanity, who took a boxful of snuff while we were waiting. Her boots were tied round the top with a piece of white rag, and she wore no stockings. Her feet and legs were very sore, and she called the doctor's attention to the latter, and his advice was, "Get a pair of new stockings when you go out" — "white ones," he added, as a parting shot. She plaintively asked in a vacant sort of moan, "Where shall I get 'em?" and the answer came from the old woman in a sharp way, which startled me, "Pinch 'em, I would," And I am sure she would.

ONCE MORE THE ORDER OF THE BATH,

and we were told to hurry up by the old inmate, who was evidently master of the ceremonies. The old woman, who was last comer, made a rush, and got into the bath-room first, and then commenced by-play which was very interesting to me in my search for information and which will be very valuable when I go on tramp for a profession. When she was out of the bath I had to get ready to go in. All the contents of my pockets were tied in my handkerchief and put on one side. As each article of dress was taken off, it was folded and put into my skirt, which was spread on the floor. Then, when no more remained, the whole was bundled together and pinned. This seems to the reader easy, but was one of the most difficult tasks I have had set me I stood in the middle of a room, dressed only in a worried look and a blush that seems to spread to one's very toes, whilst a sharp-voiced old inmate "talked at". me. The ordeal is a trying one. My turn for the bath came, and with it an injunction as binding as that of the courts to "wash my head and put plenty of soap on." Then I was given a long, clean nightdress, shown to my bed, and given three clean rugs. The bed I found to be canvas, and the first comfortable one I had come across. There were no pillows, but the head was a little raised, so that did not matter very much. When I had got settled, and had time to turn round, I found the old woman (I will call her Ann) getting her supper, which I saw was a pot of nice hot tea, with bread and butter, and something on a plate which I could not name. When ours arrived I found it consisted of cold tea and dry bread. The inmate attendant told us it had gone cold with waiting. When we had finished the pots were removed, and the light put out, and I was just dozing when a noise outside startling me, and I heard the same old sharp voice lecturing someone on the iniquities of drink. The door opened and an old woman was bundled in with some rugs, and she had to lie on the floor. I would have given up my bunk to her, but she was too "fuddled" to understand. She made a noise all night, and there was not much sleep. Next morning, at six o'clock, we were awakened, and our clothes brought in. We dressed and had breakfast. Again Ann had different food. Wo had a mug of very good coffee and dry bread, while the old inmate again provided her with butter, an onion and a mysterious something with salt to it, and as a parting gift a paper which seemed to contain a lunch. During breakfast

THE CONVERSATION TURNED TO TRAMP WARDS,

as usual. All the women with the exception of myself know them and their frequenters, so it was very interesting to me to hear the tales of smuggled pipes, etc. Enquiries were made as to who were in "the House," information was given as how many of them had been in gaol, and the tit-bit of gossip was about somebody who had "banged a bobby." The inmate attendant who had been on the road many years, had rather a bad name among the other roadsters who happened to have no money for tips. It was a great surprise to me to find that even tramps have to use "palm oil" to grease the wheels of life. We were discharged from Rochdale in a body, and in company with a woman whose next port was the same as mine, I started the walk to Manchester — about fourteen miles distant. This woman, who had managed to wash her apron while waiting for breakfast put it on wringing wet, When we got to a quiet lane she put it on the hedge in the sun while she had a smoke. This, it appears, is the habit of a professional, and when "on the rocks" they are always on the look out for "cigar ends" on the roadside. She found several and a few cigarette ends, which she called "fags." These, however, are not as welcome as cigar ends. I was glad of the rest, as my boots were getting very old and "trampy." This surprised my companion, whose clogs were split and toeless. Yet she did not mind, and trotted merrily on. She beguiled the time by telling yarns of the "mouching" of tramps, and especially of the good nature of navvies, who are always ready to pay for a pint, or give them a bit of "bacca." She was surprised because I would not ask anyone for a copper, and said I should grow out of that. However, as I would not beg she did not. She asked me what I was going to do for lodgings that night. She was not going in the tramp ward at Manchester, as it was "hell with the lid off," and if I liked I could go with her. She knew some fellows, and we could get our night's lodgings out of them, and she had a friend in Angel Meadow who would be glad to have us. I was not sure on what terms the lodging money was to be bad, or I might have gone with her, as I should have liked to have seen tramps at home. On arrival at Manchester I called on a friend and got some money, as we were

BOTH VERY HUNGRY.

I took my companion to an eating-house, and got our dinners. She was very grateful, and as a thankoffering gave me some good (?) advice "Get your lodging money anyhow, only don't go into tramp-wards. I don't, if I can mouch it anyway." And we said good-bye for ever, I trust.

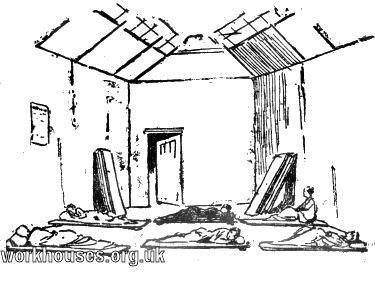

My next call was at the tramp ward that I had been told to avoid, my way leading through "mean streets." And a crowd of lads were "tossing" at the door when I arrived. I found it to be in an old mill. I made my appearance, and was sent into a room where there were a table and forms (the first table I had seen, as we had had our meals picnic fashion until now). This was the first place yet at which I was able to get a bath in comparative privacy. For this I was thankful. Clean hot water and towels were provided, after which I was taken to a large room, which at the first glance looked like a plot in a cemetery.

SLEEPING ARRANGEMENTS AT MANCHESTER.

There were about twenty "beds," which I found had to be made altogether. A number of flat boards about seven feet by three and two inches high were piled against the wall. I selected the softest, put it in line with those on the floor already occupied, arranged the rugs to the best advantage, put my head on the leather pillow, and tried to sleep the sleep of the just. But it was cruel. When the heat caused by the bath passed off I could not get warm; the nightdress and rugs were prickly, and last but not least, the united sighs, conscious and unconscious, of twenty weary women, did not tend to soothe me. I was glad when the time came to get up. My back and sides were sore and aching, and I did not wonder at the curses, both deep and loud, on the powers that be. Then a time of trial for me, dressing in that large room, and being

AUDIBLY CRITICISED ABOUT MY CLOTHING.

However, they soon found a new source of amusement in a woman who could not talk plainly, but who tried to use the most highly coloured language, and succeeded fairly well. I made out that her husband was in the male ward. There were three women with children, one of whom did not want to go out when told that those with children could do so, as she had come for sanctuary evidently. She had two of the bonniest children I ever saw — little darkies with rosy cheeks and curly hair and taking little ways. Poor little souls, I felt heartsick when I saw them bareheaded and almost shoeless, and their mother in mortal fear of their father. One of the other mothers had a baby under two and the father was in the men's ward with a little boy, while the third had a little girl about seven — a typical child of the gutter. Breakfast arrived in the shape of the inevitable gruel and dry bread. Up to now I had never seen the connection between the two, but here I did. The majority of the women broke the bread and mixed it with gruel, and put plenty of salt in. After breakfast the newcomers were put to their tasks. The labour mistress, who was exceedingly sharp, sorted us out. It was the last day of those wards, and the new ones were to be opened that night. (The irony of fate was twice revealed to me during my sojourn here. I remembered the last time a new Poor Law Building was opened and I figured in quite another character.) Here there was no ceremony, and the only banquet was the old-fashioned gruel. Not much cleaning was to be done in the casual ward. Two of us were taken across to the house and put to work. I (again the irony) had to clean the Committee Room and Clerk's room. It was a beautiful room, and it gave me pleasure to make it nice. I arranged all the chairs round the table, and fancied myself once more an occupant of one in another board room. I finished one in the forenoon and then to dinner, which consisted of cheese and bread, washed down with cold water. Then back to the house to finish the other, and the Labour Mistress was very nice to me, and complimented me on the way I had done the rooms, and I cleaned the lavatories, and was told I had done, and I went back to the casual ward. The new one was opened by this time, and we took possession. Three of the old women had been given oakum to pick; one of them was rather slow at the job, and I tried to help her, but she soon dispensed with me, as I did not do it fine enough. A little bit of this kind of work goes a long way, however, and I was very soon glad I was doing it for choice, and could give up when tired. This seems to me to be

A VERY USELESS TASK,

and one that should be abolished. The woman I helped had picked nearly two pounds, and I thought her clever.

OAKUM PICKING.

Once more gruel and bread, and then to bed at 6.30 — the new bedroom but the old beds or boards. It was not a delightful prospect, and I am afraid I sighed as much, if not so expressibly, as the ethers. The labour mistress stayed in the room while we undressed, and saw us all in bed, and once more I tried to woo sleep, but in vain. There could not have been more tossing in the Bay of Biscay on a rough night than went on in that room that night. At last morning, and it was with a glad heart that I shook my weary body and prepared for my journey onwards. Once more breakfast, gruel and bread, and farewell, and I shook off the dust of that casual ward for ever. A woman, who had been very quiet and reserved with all except myself, walked down with me. She had asked to go out the previous morning, as she had chance of a charing job, but was not allowed to do so. She was the first and only one I had met up to now who was a worker. Her husband had gone to another town a little while ago to seek work, and she had had to give up her home; being disappointed at a house where she usually cleaned on Wednesdays, she was stranded, and forced to get shelter in the casual ward, and she said that it was the first and last time. She would drown herself before she went again, and I fully believed that she meant it. That woman and I were almost the only ones in the ward who had never been in prison, and who looked for anything above a tramp ward.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.