Central London School District

The Central London School District was formed in 1849 from the London Unions of City of London, East London and St Saviour, with West London and St Martin's in the Field joining a little later.

Initially, the School District's Board of Management acquired a privately owned pauper school building in on Westow Hill in Norwood run by Mr Frederick Aubin. After the making of alterations costing about £17,000, the school could accommodate 800 children. Mr Aubin was kept on as the school's superintendent until his sudden death in November, 1860. Aubin's wife, Elizabeth, had died in 1848 and the post of matron at Hanwell was initially held by a widow named Ann Murray.

Norwood School District School site, c.1860

A picture of life at the Norwood school is provided by Charles Dickens' article London Pauper Children which appeared in the magazine Household Words in 1850. A condensed version the full article is given below.

The children, on their first appearance at this Norwood School, are usually in the most lamentable plight. Ignorance and dirt, rags and vermin, laziness and ill health, diseased scalps, and skins tortured by itch, are their characteristics. They are the very dregs of the population of the largest city in the world ... little personifications of genuine poverty — compounds, as somebody says, of ignorance, gin, and sprats.

After their introduction to the doctor, the bath, the wardrobe, and the pantry, they are handed over to the school-master or mistress, as the case may be. On the day of our visit, two hundred and forty boys were receiving instruction. in one large new school-room; two hundred (infants between two and six years old) were being taught in another room; two hundred girls were reading, writing, and sewing in a third apartment; the rest of the occupants being at work, or at drill, or at play, in other parts of the establishment. The boys are kept four days a week at school, and two days at work... the girls have three days' schooling and three days' training in household occupations, — such as cleaning the house, washing, ironing, mangling, and needlework.

The school for the eldest boys is a long room newly built, with an enormous dormitory above it. The ventilation has been provided for in a way that seems very satisfactory: By day the boys are divided into six classes, ranged on forms with. desks before them, each class being separated from the others by a curtain which hangs from the ceiling, and is sufficiently wide to separate the sections of scholars from each other, and to deaden the sounds of so large a seminary, but yet not wide enough to prevent the master as he stands on the side opposite his pupils, from getting a view of the entire school. Black boards and large slates are amongst the tools employed for conveying instruction, but the more advanced pupils are supplied with paper copy-books for writing lessons.

When the hours of teaching are over, the boys are assembled in one of the large open yards belonging to the establishment, and are there exercised by the drill-master. This official is an ex-non-commissioned officer of Guards, who in a short time makes the metamorphosis seen on parade. The ungainly, slouching, slow lout, is taught to march, wheel right or left, in concert with others, punctually and accurately. They answer the command, "left wheel," "right form, four deep," and so on, like little soldiers, and seem to like the fun. This gives them at once exercise in the fresh air, notions of regularity and prompt attention, and a habit of obedience to discipline.

There is also a naval class. Behind the school is a play-ground, two acres in extent, and in the centre of this stands a ship. True, its deck is of earth, but there are bulwarks, real bulwarks all round, and rising up above are genuine lofty masts, with rigging complete. Up these ropes the boys swarm with great delight. At a given signal they "man the yards," give three miniature cheers, and then, all in chorus, sing God save the Queen.

Besides this drill, or parade, and this exercise aloft, the boys, on two days of the week, are employed in the Industrial training of the place. The smaller boys, in classes of about thirty-five, are ranged on benches round a large tailor's shoes Patterns decorate the walls, and "corduroys " in all stages, from the huge bale to the perfect breeches, are seen all round the room. The boys stitch and sew, and make and mend, under the instruction of a master tailor, a large part of the clothes worn in the place. When each boy grows bigger he is drafted into a neighbouring shop, where, also, under a competent master, he learns the craft of St. Crispin. It is curious to see thirty or forty little cobblers, all in rows, waxing and stitching, and hammering on lap-stones, and entering con amore into the mysteries of sole and upper leathers, brads, pegs, and sparrowbills. When they have learned all these things, some of the lads pass into a third shop, where they are made acquainted with the forge, and anvil, and sledge hammer, and where they help to shoe horses, construct iron bedsteads, and make and mend all the iron-work (and there is a great deal of it) required by this family party of nearly a thousand souls — pauper children, masters, and servants, together. After going through all these stages of training, with the incidental knowledge picked up in the stables with the horses, in the playground with the dogs, when helping to feed the pigs, and whilst aiding the operation of milking the twenty-five cows which supply milk for the house, the boys have acquired a great amount of useful knowledge. The place is indeed a little colony in and if its inmates had not often to pass from it back to the sinkholes of London, they might leave Norwood almost with the certainty of becoming good and prosperous citizens.

In 1854, the School's managers debated both extending the existing school, or transferring it to a larger site elsewhere. They eventually decided on the latter course and a 136-acre site was purchased at Hanwell for £13,000. The foundation stone of the new building was laid in September 1856 as reported by the Illustrated London News

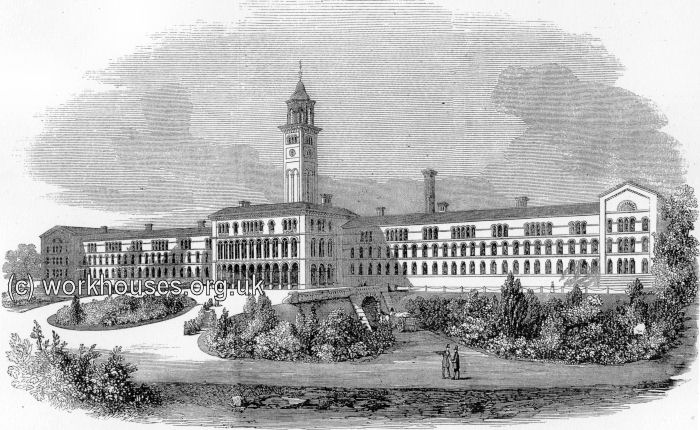

THE CENTRAL LONDON DISTRICT SCHOOLS, NEAR HANWELL, MIDDLESEX.

The foundation-stone of this extensive range of buildings now in the course of construction, near Hanwell, in the county of Middlesex, was laid on Thursday, the 11th September, by Mr. Deputy R. B. Whiteside, Vice-Chairman of the Board of Management, in the absence of the Rev. Dr. Russell, Chairman of the Board.

The district comprises the city of London Union, the East and West London Union, St. Saviour's, and the parish of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields. It was instituted in 1849, under the provisions of the stat. 8 Vic., cap 101, and placed under a Board of Management elected by the unions. The following members of the Board were present:—viz. Messrs. Thornton, Cape, Harris, Dodd. Johnson, Lewis, Bethell, Condor, Hutchings, Ward; the Chaplain to the School, the Rev. Mr. Edwards; the Superintendent, Mr. F. G. Aubin; and Mr. S. Heath, jun., the Clerk to the Board; also the Rev. Mr. Brown, Rector of Christ Church; the Rector of St. Gabriel's; Messrs Deputy Condor, Bedford, Perkins, and Elliott, of the Common Council; Messrs. Palmer Spiller, Singer, Mathews, &c., &c. There was a numerous attendance of ladies, and the boys of Harrow School were drawn up in line to witness the ceremony; when Mr. Deputy Whiteside delivered an eloquent address. The ceremony of laying the stone being completed, the chaplain of the schools offered up an appropriate prayer; after which the Hundredth Psalm was sung by the whole assembly (upwards of 300). The usual deposit of coins, &c., was made in the stone, after which the managers and their friends retired to partake of a sumptuous dinner, provided at their own expense, by Mr. Holt, of Radley's Hotel, New Bridge-street.

The School is at present situated at Westow-hill, Norwood. Its object is to receive within its walls the children of the pauper population of the district, where they are maintained and instructed. and likewise put under industrial training, so as to render them useful members of society. The premises being found inadequate, a site of 120 acres freehold land has been purchased, and the above buildings are being erected from the designs of Messrs. Richard Tress and Chambers, architects, by Messrs. Brass and Son, builders, at an estimate of about £35,000. There is a farm on the estate, in which the boys and girls will be instructed in farm labour and household ditties ; and the object of a complete separation of the children from the debasing influence of the workhouse and its inmates will be obtained.

Architect's design for Hanwell Schools, from the north-west, 1856.

The new buildings, designed by the partnership of Tress and Chambers, were erected between 1856 and 1861 at a cost of £45,000. The Hanwell Schools (plural, indicating the separate sections for boys and girls), also known as the "Cuckoo" Schools (after an old name for the area), received their first admissions at the end of 1856. A total of 1,200 children could be accommodated on the site.

Hanwell School plan of main building, 1857.

A detailed description of the new buildings was published in November 1857.

CENTRAL LONDON DISTRICT SCHOOLS, HANWELL.

The block of the building takes the form of the letter E, and consists of a central block, containing the chapel, 100 feet by 50 feet, on the first floor, with a reserve dormitory over it, and the boardroom, committee-room, and the attendant offices on the ground floor, surrounded by an open arcade or loggia. From this block, eastward and westward, are two wings, each of three stories, and about 260 feet long, containing the dormitories, the infants' school, and, adjoining the central block, the apartments of the superintendent, assistant superintendent, matron, surgeon, and other offices; the porter's, clerk's, and visiting rooms. The west wing is occupied by boys, and the east by girls and infants. Each wing consists, for the greater part of its extent, of a double suite of rooms 18 feet wide, separated by a fireproof corridor 10 feet wide, extending through the central block from endward of the building.

At the western extremity of the front, from north to south, extends a block of one story 270 feet long, occupied as the boys' school-room, 150 by 18 feet, a bath-room, and two class-rooms, each 30 feet by 18 feet.

At the eastern extremity is a corresponding block, occupied as a girls' school-room, 100 feet by 18 feet; bath-room and class-rooms same the boys'. From the central block, in the same direction, spread a more complex range of buildings, consisting of the dining-hall, 120 feet by 50 feet ; kitchen, scullery, engine and boiler room, and laundry ; and on each side, separated by a corridor of a width of 6 feet, are two narrow ranges of low buildings. Those on the west side including five small houses originally intended for the masters and their families, and the carpenter's, smith's, painter's, shoemaker's, and tailor's work rooms. On the cast side, the dispensary, a master's house, girls' kitchen and scullery, and the girls' laundry. Along the south a boundary - wall completes the enclosure.

The space between the last range of buildings and the boys' school block is the boys' yard, and the corresponding space on the east side is divided into two yards for girls and infants. In each yard a shed, open to one side only, forms a sheltered playground in wet weather, and at the end of each shed are nests of water-closets, and for the boys, urinals.

There is a basement under the centre front block, and the range of building thence southward. Access to the basement is obtained by a tunnel under the projecting portion of the central block. By this route all stores will be received into the building, and distributed into the various store-rooms into which the whole of the basement is divided.

From the centre of the building rises a tower, at present not carried up to the intended height ; in this tower is a staircase for domestic use, a coal-lift from the cellars to all floors, a dust-shoot from all floors to the cart in which it is removed, and, at the top, large tanks for the supply of cold and hot water to the building. It is contemplated to raise the tower at some future time to a height of 150 feet, for the reception of a clock and hell.

The dormitories afford sleeping room for 1,500 children, allowing 300 feet cube of air to one child. They vary in length from 80 to 150 feet, by an average width of 18 feet and height of 12 feet : they are warmed by open fireplaces; fresh air is admitted by a perforated skirting at the floor, and foul air escapes through gratings at the level of the ceiling. There are windows in the external wall and towards the corridor, and when opened together the air is at once changed and purified by the thorough draught. At one end of each dormitory is a clothes-closet, a watercloset, and an enclosed space, to contain at a future time a bath and sink.

The school-rooms are warmed and ventilated as the dormitories; they are lighted by a continuous lantern skylight at the apex of the open timber roof, and a double and opposite range of sashes under the lantern can be opened simultaneously by machinery, thereby almost instantaneously purifying the air in the dormitories.

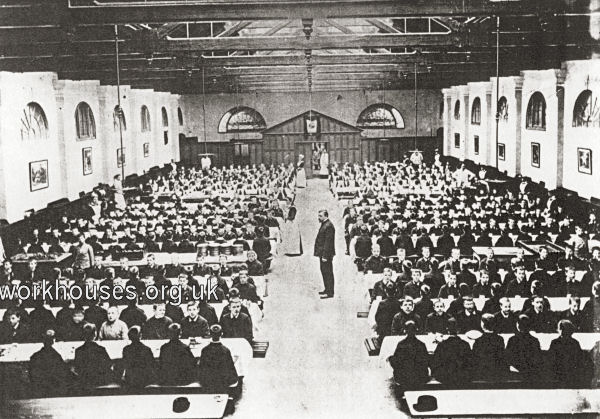

The dining-hall is also lighted by a large lantern the whole length of the ball, and 20 feet wide; and the sashes under it are similarly opened by machinery. The floor is inclined so that all the children seated are seen from the serving tables. There is space in the hall for 1,500 children to dine at once.

The kitchen and scullery are separated from the hall by the serving-room only. In the former a range of five enamelled steam boilers and steam closets constitute the working apparatus The scullery is fitted with large sinks and dressers. The bakery is on the basement near the kitchen, and consists of two large ovens and a bakehouse fitted up as usual.

There is, also, near the dining-ball, a large kitchen fitted with seven ordinary ranges, dressers, tables, &c., in which it is intended to afford an opportunity of a general knowledge of cookery to some of the elder girls.

Water is supplied to all the buildings, as well as to the farm, from a deep Artesian well, sunk to the chalk springs, in which the water rises naturally to within 10 feet of the ground line, and is thence pumped into large iron tanks over the engine-room, and into the tank in the tower.

A hot-water tank, heated by steam, supplies the baths attached to the school-rooms, the laundry, kitchens, and offices.

Gas is made at a detached gas house at some distance from the main building, and laid on to all parts of the establishment. The drainage is carried in glazed pipes from the various closets and sinks to a large subsiding tank at a distance of 1,200 feet from the nearest building. The solid portion of the drainage is there collected for use upon the farm, and the liquid refuse, after passing through charcoal, and rendered thereby clear and limpid, is discharged into the river Brent.

Access to the Schools was via the entrance at the west of the site.

Hanwell Schools entrance from the north-west, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A receiving block at the north-east corner of the school site where children were placed on arrival.

In 1890, the long main building was cut through with open spaces to produce separate but interconnected "houses". Each house contained three floors on each of which was a corridor, two dormitories and a lavatory. Each dormitory had space for between 22 and 49 beds.

The site layout is shown on the 1934 map below. By this date the buildings occupied an area of twenty acres.

Hanwell Schools Site, 1914

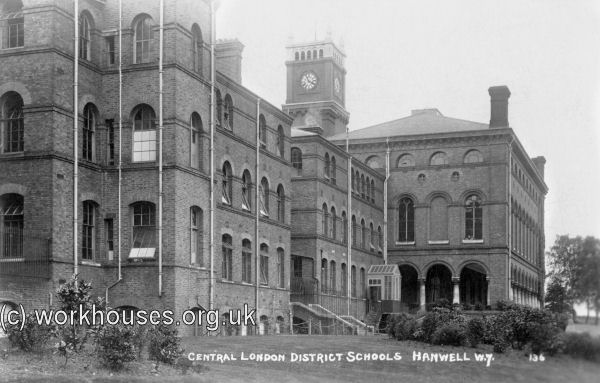

Hanwell Schools, from the north-east, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The T-shaped entrance and administration block was located at the north of the site. It contained a board room and various offices on the ground floor, with a chapel and bedrooms on the floor above. In the wings to each side were dormitories and day rooms, with boys accommodated at the west side and girls at the east.

Hanwell Schools from the north, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hanwell Schools from the north-east, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hanwell Schools from the north-east, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The eastern side wing side was two storeys high with two large dormitories on the upper floor with 38 and 49 beds in each. On the ground floor was a cloak-room, "babies'" school-room, girls' library, two bath-rooms, and a lavatory. The single-storeyed western wing contained a technical school, day-room, a school-room for boys who were in no standard, a bath-room and lavatory.

At the rear of the administration block, a large water tower held 40,000 gallons which was supplied from a well 375 feet deep and pumped up by steam engine in the basement. By 1900, the School had its own sewage and gas works and a lodge house at the end of the present Home Farm Road.

Hanwell Schools from the south-east, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

To the rear of the main block the boys' and girls' playing-yards were separated by the single-storey dining-hall with kitchens, laundry, workshops, boiler room and officers' quarters to its rear.

Hanwell Schools dining hall.

The playing-yards were paved with flagstones and contained two giant-strides, two drinking fountains, and a shed where children not possessing lockers kept their play-boxes. In 1890, a gymnasium was erected at the south of each yard.

Hanwell Schools from the north-west, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1864, a three-storeyed infirmary was built to the south of the main building. On its ground floor it had a dispensary, waiting-room, kitchen, and small laundry. On the upper floors were day and recreation rooms and the wards. Four dormitories were allocated to general cases and three for children suffering from ringworm. There was also a detached fever hospital, the ground floor of which was used for the probation of new arrivals. The school lacked any seaside convalescent home of its own but but two fortunate children were sent every fortnight to stay in a country cottage. In 1890, a large "ophthalmic school" was erected at the south-east of the site (see below).

In 1891, a separate school-house was erected at a cost of £14,000. It stood towards the south of the site, at some distance from the main building. The two-storeyed building had seven classrooms for boys on the ground floor, and six for girls and two for infants on the first floor. In March 1900, a separate infants' school was opened to its west. The new block cost £5,690 and could accommodate 250 children.

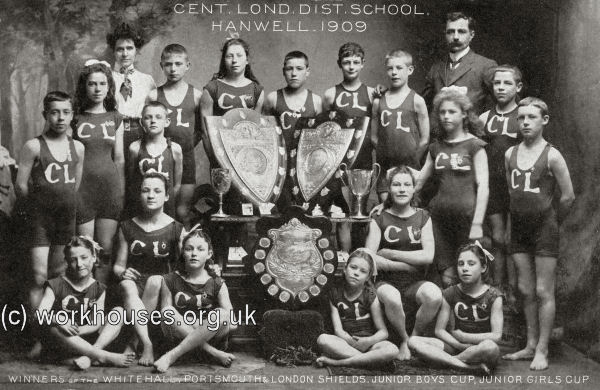

In 1891, a large swimming bath was erected at the back of the infirmary and all the children learnt to swim while at Hanwell. Swimming teams from Hanwell regularly competed against other Poor Law schools. In October 1909, at the annual competition of the Poor Law Schools' Swimming Association, the Hanwell teams carried off thirty-two prizes, three shields, sixteen medals, live certificates, and two cups, which become the property of the School.

Hanwell Schools swimming teams, 1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From around 1893, special classes, limited to 25 children, were held by the infants' headmistress for "children of defective intellect".

For many years, activities of the children were organised in two "divisions" — the working division and the school division. Up to the age of 9, children stayed in the school division and thereafter spent alternate days in each division. In the school division, they received basic education in literacy and numeracy. By the 1890s, the older boys were being taught history, geography and science. In the working division, they were divided into groups to learn and perform various occupations. For the boys this included tailoring, shoemaking, cleaning, farming and gardening, painting and glazing, carpentry, blacksmithing, and baking. The girls performed needlework, cleaning and attending the dormitories, nursery maid work, cooking, scullery and dairy work. By the late 1890s, the teaching of trades to boys at the School had been discontinued, although school work and technical training continued up to the age of fourteen. Boys were then sent either to their own homes, working boys' homes, or placed as apprentices. The older girls were given cookery lessons by a "South Kensington certificated teacher" while the matron gave special training to those intending to enter domestic service.

Children were drilled to provide both exercise and discipline, with Swedish exercises being included for the older girls. Boys were taught to play musical instruments and as early as 1865 the brass band accompanied mealtimes. Many boys went to join army bands, several becoming bandmasters.

Staff at the School in the 1890s comprised the headmaster and ten assistants (three of whom were attached to the ophthalmic school) for the boys; seven assistants (two in the ophthalmic school) for the girls; a head teacher and six assistants (one in the ophthalmic school) for the infants.

Former inmates of the School occasionally had organised visits to the establishment, revealing how they had got on in life.

An Old Boys visit to Hanwell, 1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Ophthalmia

There was a high incidence of the infectious eye disease ophthalmia amongst children at the Schools. The disease was probably carried by children transferred from the Norwood School and kept alive by the regular turnover of children arriving from the member unions' workhouses. A particularly serious outbreak in 1862 affected 686 children, with several of the younger ones losing one or both eyes. Improvement in the situation was hampered by a lack of medical knowledge and agreement about the causes and transmission of ophthalmia. In 1868, George Critchett proposed that children in the School's infirmary should be treated like those in the main school, complete with normal lessons. This, he argued, would benefit the children's education and stop convalescents being hurried back to the main school. Also, there would be less attraction for healthy children to feign illness to gain admission to the comfortable surroundings of the infirmary where they would mix with infected cases. Critchett's suggestion was dismissed as being too expensive and inconvenient. In 1874, Mr Nettleship, an inspector of metropolitan pauper schools, recommended the that severe ophthalmia cases be removed to a separate building. As a result, iron huts for 100 beds were erected and four dormitories in the school reserved for the remaining cases. However, the incidence of the disease remained high. Eventually, in 1889, following the raising of the problem in the House of Commons, the School's managers finally agreed to erect a separate ophthalmic school to accommodate 300 cases. The buildings were completed in May, 1890, at a cost of £30,000.

The Ophthalmic Institute, later known as Park School, was erected at the south-east of the main school on an 11-acre area enclosed by a six-foot wooden fence. The single-storey buildings were constructed from corrugated iron and comprised 15 dormitories, three of which were used fro sleeping and two for stores etc. Twelve large wards contained an average of 27 beds in each, and three smaller ones had 14 beds. Other detached blocks contained the kitchens, two dining halls, six school rooms, the matron's quarters, and nurses' bedrooms and mess-rooms.

Any London union could, when vacancies occurred, send children to the ophthalmic school on payment of 12s.6d. a week for each patient.

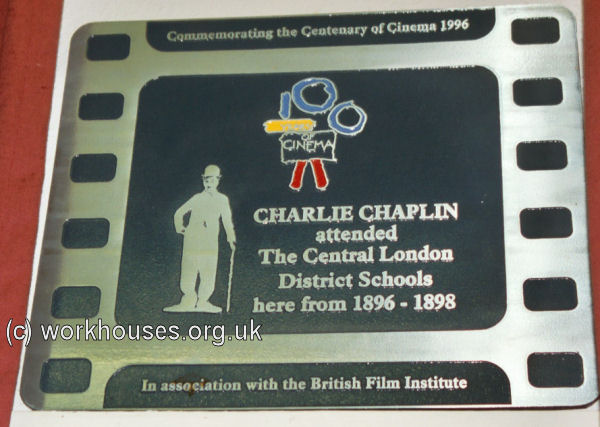

Charlie Chaplin

The most famous Hanwell inmate was Charlie Chaplin who, together with his older half-brother Sydney, was admitted in June 1896 and stayed until January 1898. They had initially spent three weeks at the Newington workhouse where their mother continued to reside. The boys were transferred to the School in a horse-drawn bakery van and spent time in the "approbation" ward after which they were separated with Charlie going to the infants' section and Sydney to the main school. In his autobiography, Chaplin recalls that on Saturday afternoon, the bath-house was reserved for the infants who were bathed by older girls — he suffered the ignominy of receiving an all-over wash with a face-cloth from a fourteen year-old.

On reaching the age of seven, he moved to the older boys' department. He recounts the story of a boy of fourteen trying to escape from the school by climbing on to the school roof and defying staff by throwing missiles and horse-chestnuts at them as they climbed after him. For such offences there were regular Friday morning punishment sessions in the gymnasium where all the boys lined up on three sides of a square. For minor offences, a boy was laid face down across a long desk, feet strapped, while his shirt was pulled out over his head. Captain Hindrum, a retired Navy man, then gave him from three to six hefty strokes with a four-foot cane. Recipients would cry appallingly or even faint and afterwards have to be carried away to recover. For more serious offences, birch was used — after three strokes, a boy needed to be taken to the surgery for treatment. Chaplin himself once received three strokes with the cane, apparently for an offence he did not commit.

Sydney, on reaching the age of eleven, left Hanwell to join the training ship Exmouth. During Charlie's remaining time at the school, he caught ringworm — an infectious disease of the scalp which was common amongst pauper children. Its treatment required the head to be shaved and treated with iodine which made sufferers the subject of ridicule by other boys. After a brief period back with his mother, Chaplin was sent for a while to the Lambeth workhouse and them to Lambeth's children's schools at Norwood. However, when Hannah was admitted to the Cane Hill Asylum, both brothers went to live with their father.

Hanwell Schools Charlie Chaplin memorial plaque, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Hanwell Schools closed in 1933 but was briefly reopened in 1934 to accommodate boys from the training ship Exmouth where an outbreak of ringworm had taken place.

In 1945, the building was adopted as the Hanwell Community Centre and continues in that role today. Many of the peripheral buildings have been demolished but the main block and former dining-hall survive.

Staff

- 1849-1860 — Superintendent: Mr Aubin; Matron: Mrs Aubin.

- 1881 Census

- 1898 — Superintendent: Mr Hall; Matron: Mrs Hall; Medical Officer: Dr Littlejohn.

- 1914 — Matron and Superintendent: Mrs. Charlotte A Hall; Chaplain: Rev. Solomon Wall Allen; Medical Officer: George Alexander Davidson; Headmaster (senior mixed department): George G Gill; Headmistress: Mrs Clara EM Fenn; Manual instructor in technical school: Frederick Drake; Steward: John R Tiffin; Band master: Charles Gregory; Engineer: William H Hildred; Assistant farm bailiff: Freeman Massey.

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

Extensive holdings (1868-1935) include:

- Minutes, agendas and reports of Board of Management and various committees; Financial accounts; Outgoing letter books; Correspondence with central authorities; Weekly returns of children at the School; Admission and discharge registers; Creed registers; Ophthalmia registers; Lists of boys and girls placed in service; Plans of the school.

- City of London Guardians: Children sent to the CLDS, Hanwell: R to Z. (1876-1929)

- Hackney Guardians: Children at Edmonton and Hanwell Schools (March 1883-October 1884, June 1887-August 1909)

- Southwark Guardians: Children sent to Hanwell Schools (1865-March 1889)

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Chaplin, Charles (1964) My Autobiography (Bodley Head: London)

- Stewart, Susan The Central London District Schools 1856-1933: A Short History by (c.1980, Hanwell Community Association)

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.