Clifton (Barton Regis from 1877), Gloucestershire

Up to 1834

Stapleton had a workhouse by 1777, when it could house 100 inmates. In 1797, the parish featured in Eden's survey of the poor in England:

Like Stapleton, the parish of St Philip & St Jacob also had a workhouse in 1777 for up to 100 inmates. It was located at the west side of Pennywell Road, later the site of Brecknell, Dolman & Rogers' engineering works. It, too, was documented by Eden in 1797, at which time its use was shared with the parish of St George and had eighty-five inmates.

St George's later had its own workhouse on what is now Hudds Vale Road. The site later became the home of the Crown Pottery.

St George's parish workhouse site (Crown Pottery), 1888.

Former St George's parish workhouse from the east

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Clifton parish poorhouse was located at the east side of Church Lane in Clifton Wood, on the hillside above Mardyke. In 1859, the building was converted for use as a boys' industrial school.

Clifton former parish workhouse site, 1886.

In 1835, the Assistant Poor Law Commissioner Charles Mott reported on his visit to the workhouse of St Philip and St Jacob on Pennywell Road:

Having been much accustomed, at one period, to visit the abodes of the poor and the destitute, in the thickly populated suburbs of the metropolis, I have not unfrequently witnessed the most appalling scenes of poverty and wretchedness; but I will confess that I was ill prepared to find in a parish containing nearly 17,000 inhabitants, expending £6O00 annually for the support of the poor, and immediately adjoining one of the most cleanly and well-regulated establishments in England, (St. Peter's hospital, Bristol,) such a disgraceful instance of neglect and mismanagement.

The state of the workhouse was filthy in the extreme, the appearance of the inmates dirty and wretched. There was no classification whatever, men, women, and children being promiscuously huddled together.

In one corner of the building I discovered a most dismal filthy looking room, which altogether presented such a sombre wretched appearance, that curiosity prompted me to explore it. I entered it, and the scene which I witnessed in it is almost impossible to forget. Judging from the appearance of the room, I should think that water must have been excluded from it for years. In short, it reminded me of a coal cellar, or any place, rather than the residence of a human being. The sole tenant of this miserable abode was a poor distressed lunatic. His appearance was pitiable in the extreme; his clothing was extremely ragged; his flesh literally as dirty as the floor; his head and face were much bruised, apparently from repeated falls. Shoes he had been furnished with at some time or other, but they had done their duty, and his feet protruded through them. He sat listless and alone, without any human being to attend upon or to take care of him, staring vacantly around, insensible even to the calls of nature, and apparently unmindful of anything which was passing in the room. He was endeavouring to avail himself of the only comfort allowed him from the few embers which were yet burning in the grate, for he had thrust his arms through an iron grating which was placed before the fire, intended doubtless to prevent the poor creature from burning himself; but as it was, his hands just reached the embers.

I endeavoured to arouse this poor pitiable fellow-creature, but the attempt was useless, all sensibility had forsaken him. To the very great shame of the parish officers, I found he had been in this disgusting state for years.

Understanding that a meeting of the magistrates would be held two days afterwards at the prison, I attended and explained to them the filthy state of the workhouse, and described to them the miserable condition of this poor lunatic. Two of them promptly consented to accompany me to the workhouse. An endeavour had been made to cleanse the place, in consequence of my previous complaints, but it was still disgusting, and the appearance of its inmate extremely pitiable. The magistrates were astounded at the sight, thanked me for calling their attention to this distressed object, and, in my hearing, directed the parish officers to be summoned before them, and promised that a strict investigation of the case should take place.

In another room in the same building, not equally deplorable with the one I have just described, but still a wretched tenement, I found another poor lunatic aged 17 years, who I was informed had been in this miserable situation nearly four years. He was almost in a state of nudity, having nothing on but a coarse shirt. Upon my asking why the parish officers allowed him to be in this deplorable condition; the answer was, "Because he tears his clothes."

After 1834

Clifton Poor Law Union was formed on 9th April, 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 32 in number, representing its 12 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

City and Borough of Bristol: Clifton (6), St James and St Paul (20, St Philip and St Jacob (7).

County of Gloucester:

Compton Greenfield, Filton, Henbury (2), Horfield, Stapleton (2), St George (4), Stoke Gifford, Westbury-on-Trym (3), Winterbourne (2).

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 51,345 with parishes ranging in size from Compton Greenfield (population 40) to St Philip and St Jacob (15,777). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1833-35 had been £17,863 or 6s.11d. per head.

Prior to 1846, the Clifton union continued to use three former parish workhouses in the area. The former St George's poorhouse in Hudds Vale Road was used for children; that in the parish of St Philip and Jacob Without on Pennywell Road accommodated able-bodied paupers; and the one in Clifton Wood was for the aged and sick. However, the Guardians eventually proposed to build a new large combined workhouse at Eastville. The reasons for this were threefold. First, there had been a large increase in pauper numbers — from 406 in 1836-7 to over 800 by 1844. Second, the very poor condition of the Pennywell Road workhouse which was overcrowded and had sick, insane and able-bodied inmates all in the same ward. It also had no infirmary ward or tramps' accommodation. One Guardian reported having found a woman there with a bastard lying dead at her side and that 'itched paupers' were not separated from other inmates. Finally, it was calculated that the annual cost of running a single institution would be £2,148-19s-9d compared with £2,682-19s-2d for three separate ones.

The Eastville (Fishponds Road) Workhouse

The new workhouse was erected in 1847 at 100 Fishponds Road to designs by Samuel T Welch. It was much extended over the years and the layout of the main buildings is shown on the 1902 map below.

Eastville workhouse site, 1902.

Eastville workhouse from the south-west, c.18905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eastville workhouse from the south-west, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eastville workhouse from the south-west, c.1920s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The front block of the workhouse complex contained the guardians' boardroom, offices, wards for the aged and infirm and for children. The front block originally contained the master and matron's accommodation but in 1892, a master's residence was erected in front of the workhouse, just to the right of the central entrance. At the rear of the front block, a central spine containing the dining-hall and chapel divided the male side at the south from the female side at the north. Either side of of the spine were a number of range running parallel to the front block. The first housed able-bodied paupers, the next contained the original infirmary, and at the rear were wards for 'lunatics' and 'imbeciles'. At the north of the front block was a nursery and accommodation for women with small children. At the south of the main complex, a new infirmary was erected in 1880 and wooden pavilion wards added in 1886. Clifton was a large workhouse with a capacity of 1180 inmates, although it was rarely if ever full.

At the entrance to the site on Fishponds Road, there were stone-breaking yards, with a casual ward providing overnight accommodation for vagrants. The stone yards were also used by non-inmates, able-bodied men who, at certain periods, attended on a daily basis to perform labour in return for out-relief.

Eastville workhouse stone yards, 1882.

In October 1867, the workhouse was the subject of an inspection report by the British Medical Journal, which found much to criticise. In the male infirmary, the use of one wash-basin and one towel a week was allowed for each ward; in the female department, similar arrangements existed, except that there was only one basin for the use of the patients in both lying-in wards. In one of the sick-wards, the only basin in the wards was retained to make poultices in; a bucket serving not only for the purpose of washing the wards, and the patients' hands and faces, but also any bad legs, or wounds, requiring such treatment, and lastly, the plates and cups. In another ward, if the patients wanted to bathe any sores etc., they had to do so in their chamber-pots. All the towels were in an extremely dirty condition. Further details are available in the full report.

In 1877, the Clifton Union was renamed Barton Regis (an old name for that part of Gloucestershire). This was at the request of the residents of Clifton parish (located at the west side of the city) who felt that the name of the parish was increasingly being tarnished when events such as outbreaks of smallpox in other parts of the Clifton Union received publicity.

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. Following a visit to Barton Regis, the commission's report found a number of matters to praise. The sick wards were furnished with bright curtains, pictures and flowers, and in the day room for infirm women, the inmates could sit and sew, look at periodicals, tend growing plants, and brew their own tea. There were, however, several criticisms. The staffing levels for the care of the sick were said to be inadequate. No night nurses were provided for the sick and infirm wards whose inmates numbered 586. The old and infirm men were tended only by untrained male nurses. Further details are available in the full report.

In 1897, the Eastville workhouse and several of the parishes in the Barton Regis Union were taken over by Bristol which was reconstituted as a single Poor Law Parish.

The Eastville workhouse subsequently became a home for the aged but was demolished in 1972 and modern housing now stands on the site. All that remains are some parts of the boundary wall and the original entrance pillars which, remarkably, still carry the number "100".

Eastville workhouse entrance pillar.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Unlike the majority of union workhouses, which buried deceased inmates in local churchyards or municipal cemeteries, Eastville had its own burial ground at the south of the workhouse (see map above) which was in operation until 1895. It has recently been calculated that around 3000 workhouse inmates were interred there, including unbaptised infants who were buried in an area referred to as "under the wall". The modern housing on the workhouse site did not extend into the burial ground and it is now covered in grass and its former use is not indicated in any way. In 2014, the Bristol Radical History Group launched a campaign for the burial ground to be recognised and those who lie there to be commemorated.

The Southmead Workhouse

In 1900-2, the reduced Barton Regis Union built a new workhouse at Southmead, intended to house 110 inmates plus 24 casuals. Its official foundation stone was unveiled on 18 September 1900 by the Duchess of Beaufort. Exactly two years later, on 18 September 1902, the completed building was formally opened by Sir John Dorington, M.P. The first inmates moved in two weeks later.

Southmead foundation stone, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

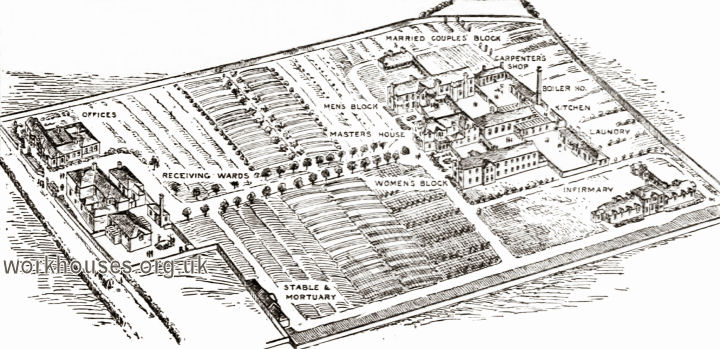

The buildings were designed by AP Cotterell and WH Thorp in a style described as "a simple type English Renaissance". The layout of the site is shown on the 1912 map below.

Southmead workhouse site, 1912.

Southmead workhouse plan — bird's-eye view from the west, 1902.

The main building adopted a pavilion-plan layout, with walkways linking the separate blocks. The central block contained the Master's quarters, with dining-hall, kitchens, and boiler house to the rear.

Southmead administration block from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Accommodation blocks lay to each side, males to the north and females to the south. A small block for married couples lay to the north of the male block.

Southmead workhouse male accommodation block from the north.

© Peter Higginbotham.

To the rear of the main building were a laundry of the female side, and a carpenter's shop on the male side. A 28-bed hospital block for females and children lay at the south of the site.

The site entrance lay at the north-west of the site on Southmead Road. Offices lay at the north side of the entrance, and receiving wards at the south. A small stables, carriage shed and mortuary block stood at the western corner of the site.

Southmead receiving block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1904, the Barton Regis Union was wound up and its member parishes dispersed between a further enlarged Bristol poor law administration, and the Chipping Sodbury Union. The new Southmead workhouse became the second in seven years to be inherited by Bristol from Barton Regis.

Southmead Infirmary male pavilion from the north-east, 2000. © Peter Higginbotham.

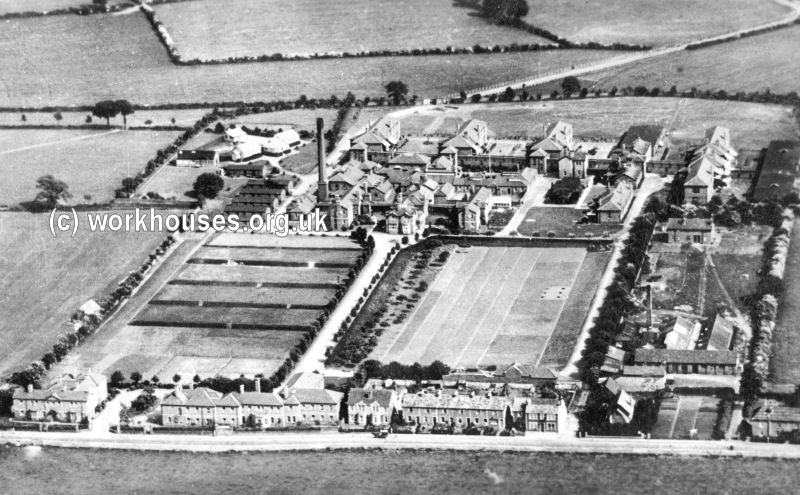

Aerial view of Southmead from the north-west. © Peter Higginbotham.

Aerial view of Southmead workhouse from the north-west (detail). © Peter Higginbotham.

The medical facilities at Southmead were rapidly expanded. During the First World War, the workhouse was taken over as an army hospital.

Southmead military hospital, c.1916. © Peter Higginbotham.

The block with the balcony in the above picture was at the south-west of the site (see aerial view below) and must have already been constructed by 1914.

Southmead aerial view from south-east. © Peter Higginbotham.

Southmead was not returned to civilian use until the early 1920s. In 1924, a large pavilion-plan hospital known as Southmead Infirmary was built at the south-east of the workhouse. The site gradually evolved into a large general hospital now known as Southmead Hospital.

Southmead workhouse site, 1935.

Aerial view of Southmead workhouse from the north-east. © Peter Higginbotham.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Bristol Record Office, 'B' Bond Warehouse (in the 'Create Centre' section from 3-Dec-2013), Smeaton Road, Bristol BS1 6XN. Holdings include: Creed register (1869-1952); Births (1868-78, 1898-1943,); Deaths (1847-1914, 1924-39); Baptisms at St Thomas, Eastville (1907-31); Register of adopted children (1899-1931).

Bibliography

- Large, David (1995) Bristol and the New Poor Law (Bristol Branch of the Historical Association)

- Summers, Marian and Bowman, Sue (1995) Of Poor Law, Patients and Professionals...

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.