Rochdale, Lancashire

Up to 1834

Township workhouses in the Rochdale area included at Spotland (100 places), Hollingworth (58), Marland (50), Calf Hey (30) and Wardleworth (24).

Spotland had a workhouse from at least 1740. In February of that year, the township Vestry appointed James Robertson as master of the workhouse at a salary of eight pounds, plus meat, lodging and washing. By 1748, 25 inmates were in residence of which 10 were aged between 61 and 82, and 7 were "children who hath no parents. Spotland erected a new workhouse in the 1780s. It was located at Spotland Bridge at the southern end of what is now Primrose Street, on the land between between Primrose Street and Spodden Street. The U-shaped building probably had two storeys plus cellars. The grounds, surrounded by a wall, also contained a number of outbuildings plus five garden plots.

Spotland Primrose Street site, 1851.

The Hollingworth workhouse stood on Syke Lane at the western shore of the Hollingworth Reservoir. (Its location is sometimes give as Butterworth, the district in which it was situated.)

Rochdale Hollingworth site, 1851.

Marland's workhouse stood at Marland Fold to the north of Marland Old Road which lay within the township of Casteleton.

The Wuerdle and Wardle workhouse was a row of cottages at Calf Hey, at the north of Wardle Fold.

Rochdale Calf Hey site, 1851.

Rochdale Calf Hey site from the south, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Wardleworth workhouse was at the west side of White Hall (Whitehall) Street between Hope Street and Castle Street (now Howard Street). The town lock-up lay at the south of the workhouse.

Rochdale Wardleworth workhouse site, 1851.

Parish burial registers from the end of the eighteenth century make reference to a workhouse at Featherstall, a hamlet at the west of Littleborough.

After 1834

The Rochdale Poor Law Union was formed on 15th February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 19 in number, representing its 6 constituent townships and parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

County of Lancaster:

Blatchinworth and Calderbrook (2), Butterworth (2), Castleton (4), Spotland (5), Wardleworth (4), Wuerdle and Wardle (2).

Later Additions (from 1894): Littleborough, Milnrow, Norden, Rochdale, Whitworth.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 52,837 with parishes ranging in size from Blatchinworth and Calderbrook (population 4,221) to Spotland (15,325).

Marland Workhouse

Rochdale was an area of vociferous opposition to the New Poor Law and the new union was set up in the face of opposition from local ratepayers. Radical opponents of the 1834 Act, led by Thomas Livesey, first attempted to boycott Guardians' elections. They then put up their own candidates who, when elected, did not attend Board meetings. Mounting pressure from the Poor Law Commissioners finally led, in 1845, to legal action being instituted against members of the Board of Guardians. Although the prosecution failed due to a legal technicality, the Commissioners persuaded local magistrates, who were ex officio members of the Board, to begin conducting union business. In April 1846, a new Board was elected and was dominated by anti-Poor Law members who continued to obstruct the Poor Law authorities.

The Rochdale Union initially continued to make use of most of the existing township workhouses. In 1866, a Poor Law Board Inspector visited each of the workhouses then in use:

Spotland was criticised for:

- The custom of two men sharing a bed at the workhouse

- The lack of workhouse dress being provided - inmates wore their own clothes.

- The allowing of smoking in both the men's and women's wards.

- The Master judging as to whether new inmates were free from infectious disease.

- The use of a cellar as a mortuary.

- The administering of medicines by illiterate pauper inmates.

At Hollingworth, described by the inspector as an "old and ill-constructed" building, 59 inmates (44 men, 12 women, and 3 children) were in residence, 15 of these being "imbeciles" or "idiots". Criticisms included:

- The allowing of smoking throughout the house.

- Bed-sharing by male inmates.

- Medicines being in the charge of a male pauper who could not read writing.

- The lack of washing facilities — the infirm were forced to use their chamber pots for washing purposes.

Afterwards, when the inspector sought out his carriage-driver at a nearby public-house, he found some of the workhouse inmates in the tap-room.

The Wardleworth site consisted mainly of the Board-room and offices of the Guardians, and of vagrant wards for the union, plus a few inmates of both sexes and all ages. The 1866 inspection criticised:

- Bed-sharing by male inmates.

- The presence of a tallow melter's" premises close to the sick wards whose stench made even the medical officer sick.

- The lack of workhouse dress being provided.

- The nursing of an infant by an 81-year-old man.

Despite this catalogue of criticisms, there was still reluctance by the union to erect a large new central workhouse.

Marland Union Workhouse / Hospital

In 1863-5, a new workhouse was erected at Marland to replace the old Marland and Calf Hey buildings. Located, just to the south of the old Marland workhouse, it was built by unemployed cotton workers during the American Civil War, as a Poor Law project, to provide paid employment. The new workhouse accommodated 260 adults and 40 children. In 1870 there were 194 paupers, none able-bodied, of which 47 were imbeciles, mostly bedridden.

The new Marland workhouse appears to have been poorly run and was again the subject of a report by an officer of the Poor Law Board. He found that diets ordered by the medical officer were rarely provided. Infectious cases wandered at will through the wards. There were few means of washing clothes, utensils or bodies. The institution's records were ill-kept and some books were missing. Medicines were administered by paupers who could not read and kept in unlabeled bottles, together with blacking and firewood, in a box. Although pauper nurses had to be able to read, the Guardians claimed that the medical officer never wrote prescriptions because the only medicine in the unlabeled bottles was cod-liver oil, as the illiterate nurses well knew. All inmates urinated into a tub in the corner of each ward — the urine was sold by the guardians for scouring cotton. The inmates had head sores and the itch and had all been dosed with sulphur, brimstone and cod-liver oil for eight months but the scratching had not stopped. Diarrhoea was endemic. All the milk was skimmed and there was no butter. Saturday was special pudding day with suet and currants 'as firm as a rock'. Monday was "lobby" day: "mutton and potatoes, frequently sour". The "lobby" was retrieved from Thursday's weekly meat dinner, after Friday's pie had been made from it. Potatoes were the only vegetable used in the workhouse and all the food was steamed. The piggery stood next to the children's yard. The pigs were fed on what the inmates could not eat and were in 'superb condition'.

In 1886, the Marland workhouse was converted for use as an infectious diseases hospital, later becoming Marland Hospital.

Rochdale Marland workhouse site, 1890.

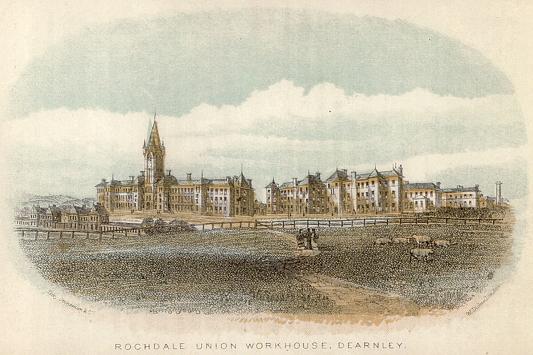

Dearnley (Birch Hill) Workhouse

In 1871, the Union purchased a 24-acre site on the slopes of Birch Hill and Starring Hill at Dearnley for £2,500. The following year, building work began on a large new workhouse.

In March 1873, the old Spotland workhouse partially collapsed, possibly because of subsidence due to an old coal-pit beneath the building. However, since the new workhouse was far from ready, the Spotland building had to be patched up and was used for another four yours. Even then its days were not over — in 1881, Rochdale Corporation were forced to rent it for use as a temporary isolation hospital during a smallpox epidemic.

The new workhouse, designed by George Woodhouse and Edward Potts, was originally intended to accommodate 632 inmates but by its eventual opening in November 1877, various extensions had increased the capacity to 847, including 29 officers. The total cost of the buildings and land was £85,000. The building was officially opened by the Mayor of Rochdale, Alderman T Schofield, on Wednesday 19th December 1877. Around seventy guests attended the ceremony which was followed by a tour of the premises and dinner at 3pm. Afterwards there were long speeches and a performance by the Orpheus Glee Club.

An 1876 sketch of Dearnley workhouse from the south-east.

Courtesy of Sandra Burge.

The location and layout of the site is shown on the 1910 map below.

Rochdale workhouse site, 1910.

The entrance to the site lay at the south as seen on the 'then-and-now' views below.

Postcard of 'Dearnley Union' entrance, date unknown.

Courtesy of Elizabeth Ellis.

Rochdale entrance from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rochdale entrance, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A pair of iron gates stood at the entrance — these have been taken down and moved elsewhere on the site.

Rochdale old entrance gates, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Inside the gates stood two entrance blocks. The one at the east contained the porter's lodge, clothing stores, and accommodation for male probationers and vagrants. The one to the west contained committee rooms, and the corresponding accommodation for males.

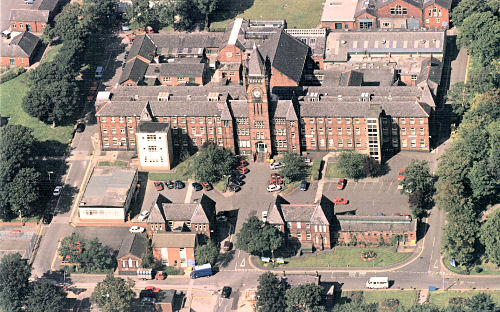

Rochdale aerial view from the south-east.

Courtesy of Rochdale NHS Trust.

At the centre of the main building were the Master's quarters, with the dining-hall (also originally used as a chapel) and kitchen and bakehouse forming the central block behind. Male inmates were accommodated to the west of the main block, and females to the east. At the rear of the main building were a laundry at the east and workshops and boiler-house to the west. The whole premises were heated by hot water pipes supplemented by an open fire in each room.

Rochdale main block from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rochdale main block entrance fireplace, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rochdale dining hall from the east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rochdale rear of main building from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the north-east of the workhouse were four detached blocks. The two at the south were male and female imbecile blocks. Behind these were an infirmary block and a fever block.

Rochdale imbecile blocks from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A school block stood to the north of the main workhouse.

Rochdale school block from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1912, a separate chapel was erected at the north-east of the school.

Rochdale chapel from the south-west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1902, a 172-bed infirmary was built at the north of the workhouse. It had a central administration block with male and female ward pavilions to each side.

During the First World War, part of the site was taken over by the military who also erected tents in the grounds.

In 1930, control of the site passed to Rochdale County Borough, with the Poor Law Institution being run by the Public Assistance Committee and the Hospital being run by the Health Committee. With the inauguration of the National Health Service in 1948, the site became a single hospital known as Birch Hill. Now run by Rochdale Healthcare NHS Trust, many of the original buildings were in use until the hospital finally closed in 2013.

Wardle Cottage Homes

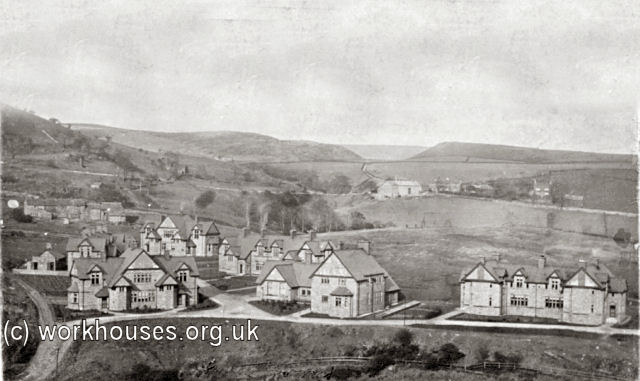

In 1898, Rochdale Union erected a children's cottage homes site at Wardle. The children lived in 'family' groups of around a dozen children, each under the care of a house 'mother' or 'father'. The buildings, which included five pairs of children's houses, were designed by P Butterworth and Duncan.

Wardle Homes site, 1932.

Wardle Cottage Homes, 1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Wardle Cottage Homes, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The site was requisitioned at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. All the homes have now been demolished.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Lancashire Record Office, Bow Lane, Preston, Lancashire, PR1 2RE. Holdings include: Guardians' minutes (1845-1900) etc.

- Local Studies Library, Touchstones Rochdale, The Esplanade, Rochdale OL16 1AQ. Holdings include: Minutes (1837-45, 1900-1930) etc.

Bibliography

- Down Poorhouse Lane - the Diary of a Rochdale Workhouse by J Cole (1984).

- Marland as a Workhouse in Eavesdropper (Rochdale Health Authority, September 1986).

- Robertson's Guide to Rochdale (1876).

Links

Acknowledgements

- Thanks to Elizabeth Ellis, Sandra Burge, and Pam Godman for contributing to this page.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.