Labour Colonies

The 1890s saw the appearance of the labour colony, an establishment — usually in a rural location — where unemployed or destitute men could live and undertake work in return for their board and lodging and, in some cases, a small wage. Over the next four decades, colonies were set up by a number of organisations and varied in the aims. A colony could be an alternative to the workhouse, a preparation for emigration, or a 'corrective' institution for those unwilling to find employment.

Labour colonies were not an entirely new idea, however, and can trace their origins from schemes such as the agricultural colony for reforming delinquent boys established at Mettray in France in 1839. The Mettray colony was the result of a collaboration by penal reformer Frédéric-Auguste Demetz and architect Guillaume-Abel Blouet who believed that rural surroundings, contact with the land, and community-forming architecture, together with religious instruction, would bring about remedial changes.

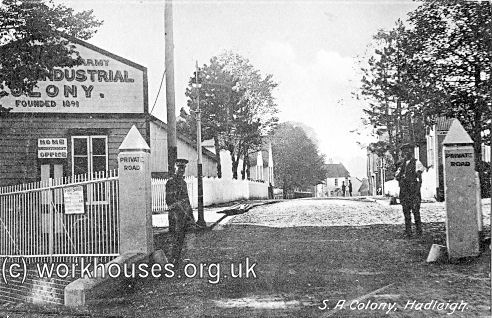

The Salvation Army Colony at Hadleigh

A proposal for a 'Farm Colony' was put forward by Salvation Army founder William Booth in his 1890 book In Darkest England, and the Way Out. Booth's idea was to assist the nation's destitute men by resettling them 'on an estate in the provinces, in the culture of which they would find employment and obtain support.' The scheme was realised at Hadleigh in Essex where a 3,200-acre estate was acquired in 1891. The land was out of cultivation and much work was needed. By the end of the year, a number of temporary buildings had been erected, including a dining-room, kitchen, five dormitories, bathroom, offices, and a reading room. A 16-bed hospital was opened in October, and large citadel or meeting hall was also built on the site.

Around 400 men passed through the Colony each year, with around 230 there at any one time. Men arrived at Hadleigh most often as a referral from the Army's Central Labour Bureau, or after working for a spell in one of the Elevators. Workers received their board and lodging plus a cash 'grant' of between 6d. and 5s. per week depending on their ability.

Hadleigh Colony entrance, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hadleigh Colony 'Castle Avenue', c.1910.

Hadleigh Colonists at work, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Colonists produced a variety of field crops, such as wheat, cabbages, and onions, and grew tomatoes in glass-houses. Hadleigh was also noted for its poultry. Financially, the Colony regularly ran at a loss, a situation which the Army attributed to the poor performance of its labour-force, 92% of whom had a history of drink problems.

As well as providing accommodation and productive employment, Booth's intention was that their time there would equip many of the men for living in his project for an 'Oversea Colony'. Many men who worked at the Hadleigh Colony did indeed subsequently emigrate to Canada.

Part of the Hadleigh site is still used by the Salvation Army as a training centre for adults with special needs.

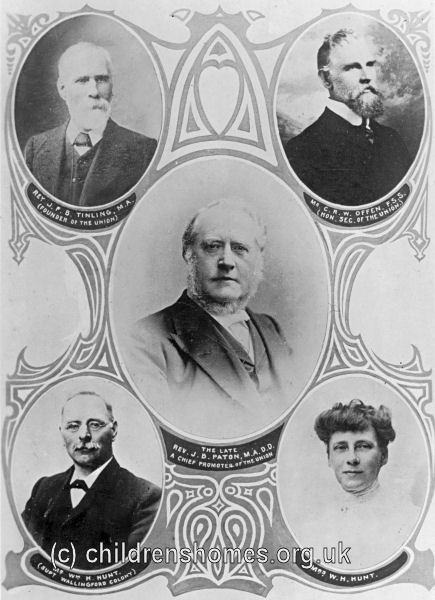

The Christian Union Colonies

In 1897, during a period of trade depression, a group of concerned social workers formed the National Union for Christian Social Service (NUCSS, also known as the Incorporated Union for Christian Social Service, and later as the Christian Service Union) to assist the unemployed. Later that year, NUCSS established a 250-acre farm colony at Lingfield in Surrey as a training institution, initially for a dozen men. Lingfield's intake mainly comprised able-bodied male paupers placed there by metropolitan poor law unions and parishes.

Leading figures in the NUCSS, c.1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

NUCSS subsequently took over a farm colony at Starnthwaite in Westmorland, originally started by the Rev. Herbert Mills, of Liverpool. However, both it and Lingfield were turned over to the care and training of epileptics, something which had become another active NUCSS concern. In their place, new colonies were opened in 1908 at Marple Dale, in Cheshire, and in 1912 at Benson, near Wallingford, in south Oxfordshire.

A report (abridged) on the new Marple Dale colony noted:

The site of the new farm colony for the Manchester unemployed has now been purchased, and work is being started at once. The estate consists about twenty-seven acres of good alluvial land the Goyt Valley, between Marple and Romiley. The land lies the Cheshire bank the river, and known as "The Marple Dale Farm." Mr. Harry Nuttall, M.P., has bought the estate and letting it a low rental to the representatives the colony, with an option of purchase them within three years.

There is a substantial stone-built farmhouse on the estate, containing living-room, kitchen, and three bedrooms, with stables, barn, and other outhouses adjoining. In the opinion of experts the land is admirably adapted for market gardening, fruit, and flower growing, and poultry rearing. The soil is rich and loamy. The farm lies hollow, well sheltered from the winds, a charming piece of scenery.

The scheme will worked much on the lines of the successful League-of Help Farm Colony at. Bradford. The men will chosen from the Manchester Labour Registry. They will housed, and will receive the equivalent of ten shillings wages per week. About five shillings will be retained for food: each man will receive email personal allowance a shilling per week; the balance of four shillings, in the case of married men, will be paid each week towards the maintenance of their families, and in the case of unmarried men will held for them and repaid to them leaving the colony. This is simply a maintenance wage. The main object of the colony is to train the unemployed in farming and market-gardening, and incidentally in habits of thrift, and industry, so that they may obtain similar employment, elsewhere, and ultimately make their living on land of their own by the help of the Small Holdings' Act. It will thus, it is hoped, serve as a kind agricultural college for the unemployed on a small scale.

The Marple Dale colony closed in about 1930.

The Wallingford colony initially comprised 515 acres and accommodated 120 colonists who were divided into two sections: youths under twenty-one, and men from twenty-one to fifty. Again, around ninety percent were sent by Boards of Guardians. A feature of the training at the Wallingford colony was the participation of 'brothers' — men 'who give themselves to the work from altruistic motives and share the life of the colonists.' The aim of the colony was to prepare men either for emigration to none of the British colonies, such as Canada, or for employment on an English farm.

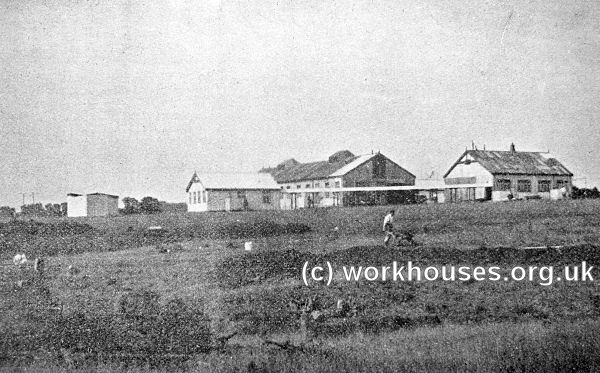

The Wallingford (Benson) Colony, c.1912.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Later known as Turners Court Farm School, the Wallingford establishment continued in operation until 1991.

The Poplar Union Colony at Laindon

In 1904, the Poplar Poor Law Union in London's East End set up a 'labour colony' — effectively a branch workhouse for able-bodied men — on the 200-acre Sumpner's Farm it had purchased at Dunton near Laindon in Essex. Through a scheme known as the modified workhouse test, unemployed men were admitted as workhouse inmates with their wives and families also being given out-relief. The colony, for up to 100 inmates, was intended to introduce more productive activities into the labour test — farm work instead of stone breaking and oakum picking — and to encourage self-sufficiency amongst the able-bodied poor. The scheme was financed by Joseph Fels, a wealthy American philanthropist.

In its early days, the scheme was hailed as a great innovation. Problems soon arose, however. There was no high wall surrounding the colony site and as a result men regularly slept out, begged, and frequented local public houses. The land, of an areas which would normally have required only four labourers for its cultivation by plough, was instead dug over and over by the men with spades, a practice which became as futile as the work it was intended to have replaced. The experiment was ultimately deemed unsuccessful and the colony scheme ended in 1912.

Poplar Labour Colony, 1904.

Poplar Labour Colony - digging a reservoir, 1904.

The Hollesley Bay Colony

The first training establishment at Hollesley Bay, near Woodbridge in Suffolk, was the commercially operated 'Colonial College and Training Farms' opened in 1887. The College, founded by Robert Johnsons, aimed 'to provide, for those intending to emigrate, a thoroughly sound and practical training before their departure.'

The College closed in 1903 and two years later the site, again with financial support from Joseph Fels, was acquired by the Central Committee of the London Unemployed Fund (later the London Central (Unemployed) Body) and renamed the Hollesley Bay Farm Colony. The Colony aimed to take unemployed men from London, up to three hundred at a time, and give them training in farm work and other rural industries. Men who proved successful could then be resettled with their families with permanent employment either on the Colony's own estate or elsewhere. The scheme gained some success with the Colony becoming an agricultural showpiece, especially known for its orchards and soft fruit trees.

Hollesley Bay Labour Colony main building, date unknown.

In 1938, Hollesley Bay was taken over by the Prison Commission as a training institution for young offenders as part of the Borstal system. The site is still in use as an open prison for adult male offenders.

Ministry of Labour Instructional Centres

Between 1925 and 1939, the Ministry of Labour operated a number of training and work camps. The earliest of these, at Claydon in Suffolk, began operation in 1925 in the former Bosmere & Claydon union workhouse. Up to 200 unemployed men aged 19 to 25 (or ex-servicemen up to the age of 29) were trained either as 'handymen' for employment in Britain, or were prepared for work on the land in Britain's overseas Dominions, primarily Australia and Canada. A second camp at Brandon, Suffolk, opened in 1926 and performed a similar role to Claydon.

In 1929, an agreement was made with the Canadian government for the placing on the land in Canada up to 6,000 'trained and tested me'. Accordingly, four further centres were established, namely, at High Lodge, West Tofts and Cranwich Heath — all in Norfolk — and at Carstairs in Scotland. The new Norfolk sites were all on land leased from the Forestry Commission, while at Carstairs two farms with area of 1,000 acres were purchased. Five further 'testing' centres were also established at Bourne in Lincolnshire, Fermyn Woods near Brigstock in Northamptonshire, Presteign in Radnorshire, Swanton Novers near Melton Constable in Norfolk, and Shobdon in Herefordshire. The testing centres offered short placements as a preliminary to selection for assisted passages and occupied men in clearing Forestry Commission land prior to re-afforestation.

However, rising unemployment in Canada curtailed the planned emigration scheme. Some of the centres were close and the remainder designated as Transfer Instructional Centres (shortened to just Instructional Centres in 1931) which aimed to physically harden or 'recondition' men who were said to have become 'soft' through a period of unemployment, particularly in unemployment blackspots such as coal-mining areas. Such men were coerced into attending the camps under the threat of losing unemployment benefit. The Centres continued in operation until 1939, with annual admissions reaching a peak of more than 24,000 in 1936.

Bibliography

- Field, John (2009) Able Bodies: Work camps and the training of the unemployed in Britain before 1939. (University of Stirling, Institute of Education - staff paper)

- Sladen, C (2011)

Oxfordshire Colony: Turners Court Farm School, Wallingford, 1911-1991

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.