Medical Care in the Workhouse

Up until the 1870s, the medical treatment provided in workhouses left much to be desired. Virtually all workhouses had a small infirmary room or block for the care of sick inmates. However, this was often too small, badly ventilated, and with poor sanitary facilities, Different categories of patient were often mixed together, sometimes even in the same bed. Poor Law unions were obliged to employ one or more suitably qualified medical officers to minister to the union's sick poor, both inside and outside the workhouse. Unfortunately, the post of medical officer was not always a particularly attractive one. Until 1842, posts could be put out to competitive tender, with the appointment usually being made to whoever demanded the lowest salary. This meant that applicants were often the least experienced members of the profession, or ones with private practice where the physician's priorities would invariably lie. Apart from attending patients, medical officers usually had to pay for any drugs they prescribed.

Early nursing care in the union workhouse was invariably in the hands of female inmates who would often not be able to read — a serious problem when dealing with labels on medicine bottles. Such nurses were also often drunk, with commonly prescribed spirits such as brandy either being purloined in transit to the patients or traded by their recipients in return for food or attention from their carers. Before 1863, not a single trained nurse existed in any workhouse infirmary outside London.

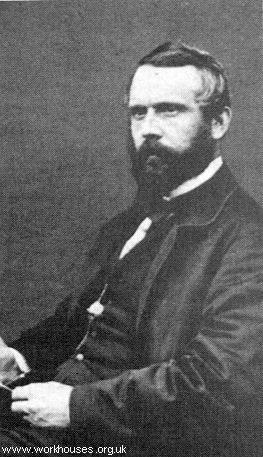

From the late 1850s onwards, pressure began for improvements in workhouse medical care, particularly in London. Some of the most notable campaigners were Louisa Twining — a prominent figure in the Workhouse Visiting Society, Joseph Rogers — medical officer (and severe critic) of the Strand workhouse, Florence Nightingale, and the medical journal The Lancet. In 1865, The Lancet began a serious of detailed reports about conditions in the capital's workhouse infirmaries. Its description of St George the Martyr in Southwark was typical of what it uncovered:

Joseph Rogers

As a result of such reports, the government was forced into action and in 1867 the Metropolitan Poor Act was passed, requiring London workhouses to locate their hospital facilities on separate sites from the workhouse. The Act also led to the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board which took over the provision of care for the sick poor across the whole of the capital. It set up its own institutions for the treatment of smallpox, fever, tuberculosis, and venereal diseases, effectively laying the foundations for the National Health Service.

Florence Nightingale's campaigning also led to improvements in the standard of nursing care, particularly with the founding in 1860 of the Nightingale Fund School at St Thomas's Hospital.

Florence Nightingale

© Peter Higginbotham.

Outside of London, Liverpool pioneered the use of trained nurses through an experiment in 1865 funded by local philanthropist William Rathbone. He financed the placement in the workhouse infirmary of twelve nurses trained at the Nightingale School. These were assisted by eighteen probationers and fifty-four able-bodied female inmates who received a small salary. Although the experiment had mixed results — the pauper assistants needed constant supervision and obtained intoxicants at the slightest opportunity — it was generally perceived overall to have been a success, in large part due to the efforts of the infirmary superintendent, Agnes Jones. Eventually a skilled nursing system spread to all union infirmaries in the country.

Agnes Jones

© Peter Higginbotham.

Despite the gradual improvement in medical care, standards in smaller provincial workhouses often lagged behind the larger establishments in London and other urban areas. In 1894, the British Medical Journal began a campaign to expose the poor conditions that still existed in many workhouses. Over the following two years, workhouses across England and Wales, and then Ireland, were visited by a BMJ "commission" and their — often shocking — inspection reports published in the Journal. The BMJ's efforts undoubtedly resulted in further improvements in the standard of care, particularly for the elderly, sick and infirm, that was provided in the nation's workhouses.

One particular burden that workhouse infirmaries had to bear was that of patients with venereal diseases, sometimes known as "lock" cases. Such cases were often refused admission to charitable and subscription hospitals, or would be offered only one course of treatment. Many workhouse infirmaries had special sections — the foul wards — set aside for this type of patient.

Originally, workhouse infirmaries were intended solely for the care of those resident in the workhouse. The beginnings of a change in this practice came with the establishment of the Metropolitan Asylums Board in 1869 which provided certain types of medical care for all London's poor. From the 1880s, admission to workhouse infirmaries was increasingly permitted to those who — though poor — were not sufficiently destitute to require entry the workhouse. Like all recipients of union relief, such patients first needed to have their means assessed by the union relieving officer and, where appropriate, might be required to contribute towards their maintenance whilst resident in the infirmary. Prior to 1918, receipt of poor relief disqualified the recipient from voting. The 1885 Medical Relief Disqualification Removal Act recognised the widening of access to workhouse infirmaries and provided that anyone who was in receipt only of poor-rate-funded medical care no longer lost their vote.

The admission of non-paupers to workhouse infirmaries led to a widespread expansion infirmary buildings. This, coupled with a growth in the numbers of trained nursing staff, resulted in a major improvement in workhouse medical care. The workhouse medical service marked the beginning of Britain's state-funded medical service, proving free treatment for those who would not otherwise be able to afford it. Although there ware many charitably funded voluntary hospitals, they were often selective in who they admitted and generally did not offer long term care for the chronic sick or the elderly. In some workhouses, the medical provision steadily expanded to the point where it outgrew the establishment's role of housing the destitute. When Britain's National Health Service was inaugurated in 1948, a large proportion of its real estate came from former workhouse and poor law establishments.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.