Manchester, Lancashire

Up to 1834

A Parliamentary report of 1776-7 listed a workhouse in Manchester accommodating up to 180 inmates. Also included were workhouses at Cheetham (25 inmates), Failsworth (20), Harpurhey (10) and Great Heaton (6).

A workhouse was built in 1792 on New Bridge Street in Manchester. It was opened for the reception of the poor on February 14th, 1793.

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England reported of Manchester that:

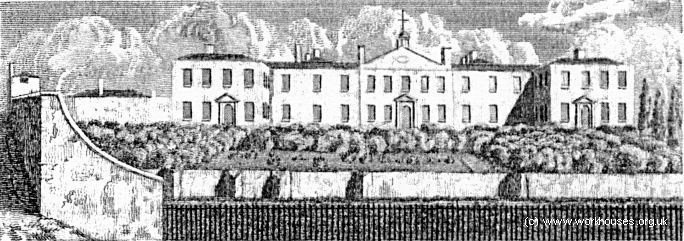

Manchester New Bridge Street workhouse from the west, 1820s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester New Bridge Street from the north, 1816.

An early nineteenth century account described the workhouse as:

A manufactory of cotton goods is carried on in the house in which the stronger poor are employed and the children are instructed in the arts of winding, warping and weaving... The average number of paupers of all ages, supported in the house, is from 350 to 400, whose board costs per head, from three shillings and six-pence to four shillings per week.

Below are the accounts of provisions used by the workhouse for the year April 1803 to April 1804:

Manchester provisions accounts 1803-4.

A flavour of life in the workhouse from around this period comes in its set of "house rules":

THE POOR IN THE HOUSE

are required

TO OBSERVE THE FOLLOWING RULES

That they obey the Governor and Matron in all their reasonable commands.

That they demean themselves orderly and peaceable, with decency and cleanliness.

That they never drink to excess.

That they be diligent at their work.

That they work from six o'clock in the morning till six at night, in summer; and from seven o'clock in the morning till such hours in the evening, as the Directors shall appoint, in the winter; except Saturday afternoons, from four o'clock; and on Good Friday, Christmas Day, and the two days following, and Monday and Tuesday in the Easter and Whitsun Weeks, which are to be regarded as Holidays.

That they do not pretend sickness, or other excuses to avoid their work.

That they do no wilful damage, but execute their work to the best of their abilities. — Such rewards and gratuities shall be distributed to the industrious and skilful in proportion to the quantity and perfection of their work, as to the Church-wardens and Overseers shall seem reasonable. (Man. Act. Sec.36)

That they regularly attend divine service on Sundays, and prayers before breakfast and supper every day.

That they go to breakfast, and to supper, in the Dining-Hall, when summoned by ring of bell.

That they be allowed half an hour at breakfast, and an hour at dinner.

That no strong or spirituous liquors be allowed in the House, except by order of the Physicians or Apothecary.

That they do not curse, nor swear, nor lie.

That they do not steal, sell their provisions, or sell or pawn their clothing, nor be guilty of any other breach of trust.

That they never go out during working hours, nor at any other time, without leave.

That when permitted to go out, they do not stay longer than the hour appointed.

WHOEVER shall offend against the above Rules, will be punished either by confinement in the stocks, or in the dungeon, or elsewhere, or by distinction of dress, by abatement of diet, loss of gratuity, by such corporal or other punishment as may be determined and adjudged by the Weekly Board of Overseers, according to the powers vested in them by the Act of Parliament.

The Rules shall be read to the Poor in the House by the Governor on the first Monday in every month.

After 1834

The Manchester Poor Law Union was formally declared on 11th December, 1840. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 24 in number, representing its 12 constituent townships as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

County of Lancaster: Blackley, Bradford, Cheetham, Crumpsall, Failsworth, Harpurhey, Great Heaton, Little Heaton, Manchester (13), Moston, Newton (in the Parish of Manchester), Prestwich.

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 164,130 with parishes ranging in size from Bradford (population 166) to Manchester itself (142,026). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1838-40 had been £34,173 or 4s.2d per head of the population.

The growth-rate of Manchester in the 1840s led, in 1850, to the township of Manchester becoming a Poor Law Parish in its own right. The other members, covering an area to the north and east of the city, separated to form the new Prestwich Union.

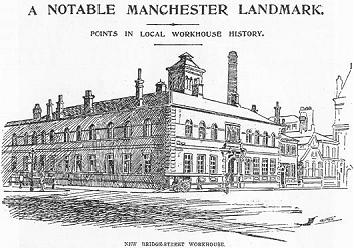

The Bridge Street Workhouse

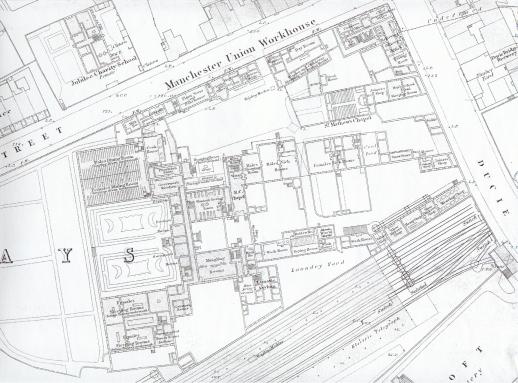

The Manchester Union took over the Bridge Street workhouse which was enlarged in 1843. The workhouse layout is shown on the 1848 map below. (Click on the map for an enlarged version.)

Manchester New Bridge St, 1848

A striking description of the workhouse and its environs was written by Frederick Engels in 1845 in his Condition of the Working Class in England:

New fever wards were added to the buildings in 1851. By the 1860s, the New Bridge Street workhouse could accommodate 1,644 inmates.

In August 1866, the workhouse was visited by Poor Law Board Inspector Mr R.B. Cane. His report noted:

Nearly all the beds, even for the sick, are of straw, though of course other beds are provided for particular cases. In visiting the sick wards, I specially and in the absence of the officer who withdrew at my request, inquired of each patient in a condition to understand and reply to my questions, whether he or she had any complaint to make either in regard to their food, their bed, their clothes, or their attendance, and whether generally they were contented and satisfied with what was done for then. The answers to my inquiries were (with hardly any modification) satisfactory in these respects. I found that the sick were duly supplied with the diet, wine, beer, spirits, &c., ordered for them by the medical officer. Not only were they generally contented and satisfied, but I run happy to add that many of them expressed gratitude for the care and attention bestowed upon them.

There is, however, much dissatisfaction in regard to a portion of the diet. The pudding is considered hard and indigestible, and it is said to be absolutely rejected and wasted by a large number of the inmates. The rice as a meal is distasteful to many, whilst the pea-soup disagrees with some of the aged poor. The old women especially complain that their tea is not good of the kind, and that it is too weak. I tasted it myself and consider that it may well be improved in strength and flavour.

I found the workhouse generally in fair order throughout, but some of the beds are too near together. Ventilation is especially defective in the Magdalen wards, and I am inclined to think that one of the old women's wards is too full. Many counterpanes in the sick ward require washing, and there is not a sufficient supply of towels, &c., in those wards.

Prayers have not lately been said in the evening, and the chaplain's report book does not contain a report of the moral and religious state of the inmates of the workhouse.

Manchester's aged and infirm remained at New Bridge Street until 1875 when the main part of the site was sold to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway for an extension to Victoria station. In 1881, the remaining part of the site was redeveloped with the erection of new casual wards, relief department, female lock (venereal) wards, lying-in wards, and lunatic wards. The New Bridge Street premises continued in use until the First World War when the War Office took over the premises. These were demolished in the 1920s to expand the Victoria Station's goods yards.

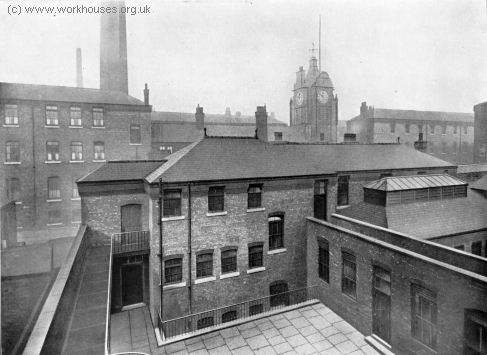

New Bridge Street site, 1908.

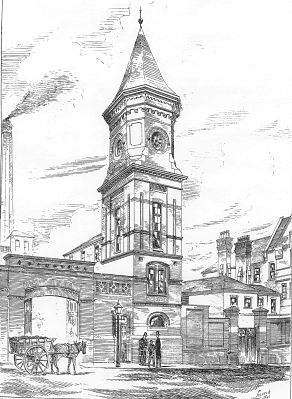

Entrance to new New Bridge Street casual wards, 1881

Ancillary Workhouse Sites

As well as Bridge Street, two other existing workhouses were retained by the Manchester Union as children's establishments. The former Blackley parish workhouse on Moston Lane was converted for used as a school for the union's pauper boys. Its location is shown on the 1848 map below. A small lunatic asylum was located to its west.

Blackley workhouse boys' school, c.1848.

In a similar manner, the old Prestwich parish workhouse at Rainsough was used as a residential school housing about 160 pauper girls.

Rainsough workhouse girls' school, c.1848

The Blackley workhouse closed in around 1845 after the opening of the Swinton Schools (see below) and was subsequently leased for use as a silk mill. The Rainsough workhouse was used for period to house adult inmates but was given up in 1847. After the formation of the Prestwich Union in 1850, Rainsough became the new union's workhouse.

At the height of the Irish famine in 1847, Manchester experienced a large increase in poor relief claimants, partly due to an influx of immigrants and partly due to a widespread outbreak of typhus fever in the city. As a result, the Bridge Street workhouse could not cope with the demand for places and additional accommodation was needed. In January 1847, the union began leasing the former Barratt's mill premises at the north end of Tib Street as a temporary auxiliary workhouse for 600-800 inmates. The Tib Street workhouse, also known as the House of Industry, was mainly used as a 'test' workhouse for able-bodied men who were required to perform labour in return for poor relief. The workhouse was vacated in early 1851.

Manchester Tib Street site, 1847.

From July 1847, further workhouse accommodation was established in premises on Canal Street. This continued in use until October 1858 after the new workhouse was opened at Crumpsall.

From about a year from July 1847, a temporary workhouse for about 200 inmates operated on Minshull Street. Over the same period, a temporary fever hospital was in use on Millgate — this establishment closed in June 1848.

The Crumpsall Workhouse

In 1855-7, the Manchester Board of Guardians erected a new union workhouse on an out-of-town site at Crumpsall, up the Irwell valley to the north of the city. The workhouse, designed by Mills and Murgatroyd, could accommodate 1,660 inmates, comprising: 745 able-bodied men and women; 152 women including 76 with infants; 248 idiots, imbeciles and epileptics; 255 children under 16; 60 probationers; 200 sick.

The first inmates at Crumpsall, in 1857, were able-bodied males who worked on the workhouse farm. Inmates only began living in the main workhouse from around August 1858.

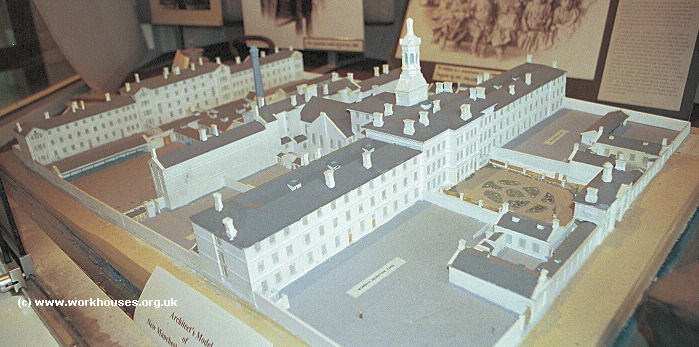

An good overall impression of the buildings is given by a model of the site.

Manchester workhouse model from the south.

© Peter Higginbotham.

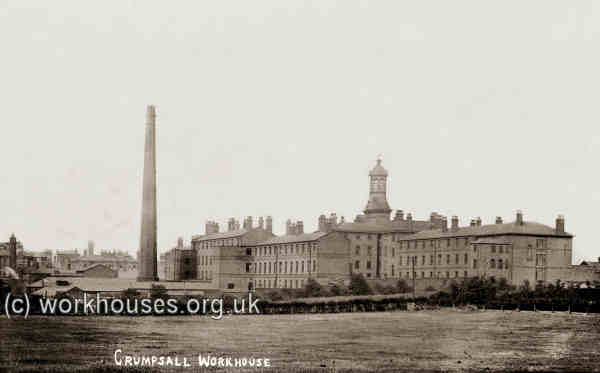

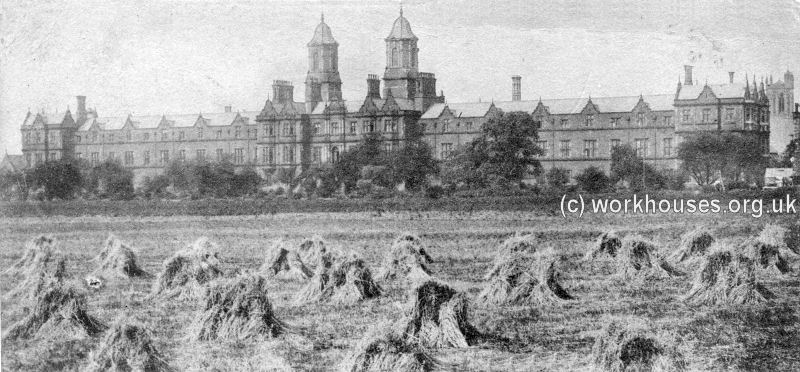

Crumpsall workhouse site from the west, c.1906.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Between 1909 and 1920, new blocks were erected at the west and south sides of the workhouse, providing new inmates' dormitories and accommodation for imbeciles. The new block at the south, hiding the base of the chimney stack, can be seen in the picture below.

Crumpsall workhouse site from the west, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The main entrance to the workhouse was via the block at the south-east where a porter's lodge was placed alongside a central archway.

Manchester workhouse entrance block, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester workhouse entrance block (detail), early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester workhouse entrance block (detail), early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham.

To the rear, the main building was as large T-shaped block.

Manchester main block from south-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A link block containing the chapel led to two long parallel accommodation ranges.

Manchester chapel (left) and accommodation block (centre) from the north-east, 2000. © Peter Higginbotham.

Crumpsall was also visited by Poor Law Board Inspector Mr R.B. Cane in August 1866 at which time accommodation was provided for 1,963 inmates. He found it to be "...the most complete as well as one of the best managed work-houses that I have ever inspected. It is in thoroughly excellent order throughout, and generally in such a state as to reflect the highest credit on all concerned in its management and care."

After the closure of most of the New Bridge Street site, a large pavilion-plan infirmary was erected at Crumpsall, to the north of the workhouse. The 1893 map below shows the site layout at that time, with the adjacent Prestwich Union workhouse at the north.

Manchester Crumpsall Map, 1893.

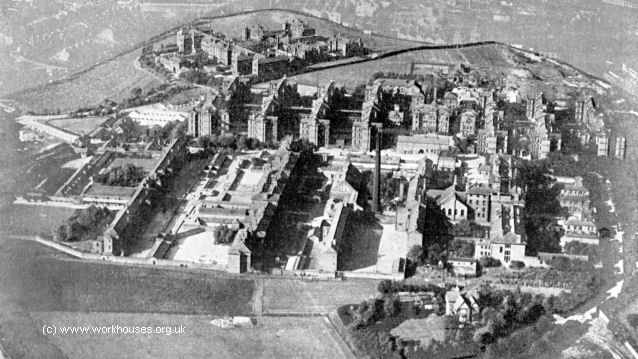

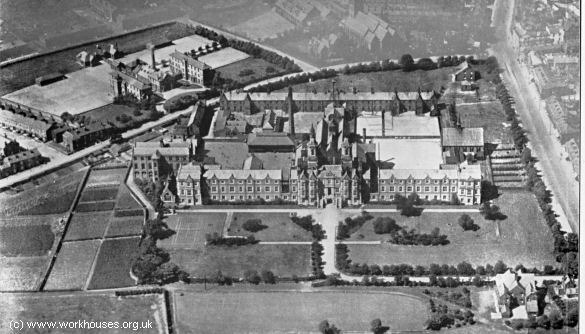

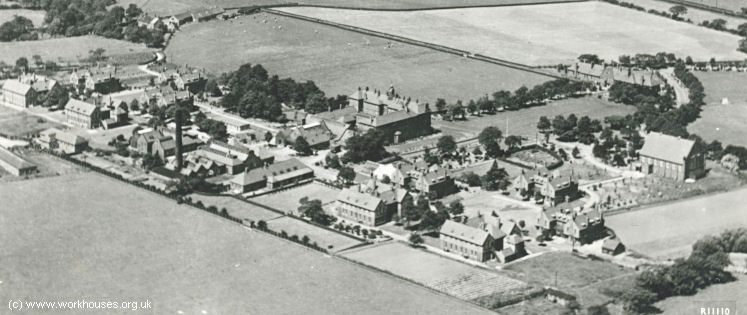

The 1920s aerial view below shows the Crumpsall site viewed from the south, with the workhouse in the foreground, the infirmary at the centre, and the Prestwich Union workhouse in the background.

Crumpsall workhouse site, 1920s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester Crumpsall infirmary administration block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester Crumpsall infirmary, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Manchester Crumpsall infirmary pavilion blocks from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After the erection of the infirmary, a new laundry was built to serve both it and the workhouse.

Manchester Crumpsall laundry block (right), 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Another surviving building is the Master's residence, a little way to the south-west the main block.

Manchester Workhouse Master's house, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

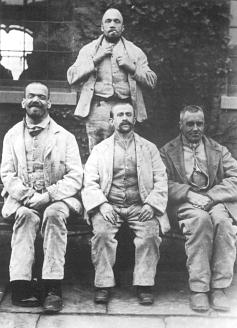

Manchester workhouse male inmates, 1890s.

Manchester workhouse inmates old and young, 1890s.

Manchester clay pipes recovered from the stone yard, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 123 (later 223) Crescent Road, Crumpsall.

In 1915, the Poor Law Unions in the Manchester area underwent a major re-organization, with the South Manchester (formerly Chorlton) and Prestwich Unions amalgamating under the control of the Manchester Board of Guardians. As part of this change, the Crumspall site was renamed the Crescent Road Institution.

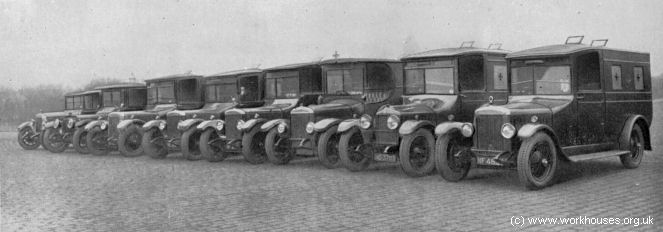

By 1930, the Manchester Union had its own fleet of eight ambulances.

Manchester Union ambulance fleet, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

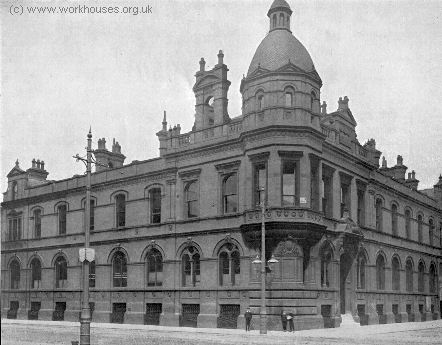

The enlarged Manchester Union adopted the former Chorlton Union offices on Grosvenor Square.

Grosvenor Square Offices, c.1930.

With the official abolition of workhouses in 1930, the Manchester workhouse came under the management of the Manchester Public Assistance Committee, while the infirmary came under the Hospitals sub-committee of Public Assistance Committee. Now known as Crumpsall Institute, the former workhouse, which had always had its share of lunatic inmates, started to become a centre for treatment of the mentally ill. Crumpsall Institute was renamed Park House in 1939, and with the introduction of the National Health Services in 1948, became Springfield Hospital.

Swinton Industrial School and Swinton Home

Manchester was one of the first unions to set up a large separate institution specifically for pauper children. The building, erected in 1843-5 at Swinton, was designed by Richard Tattersall. It was a long three-storey T-shaped building, with two tall towers and Dutch gables. Separate Anglican and Roman Catholic chapels were erected at either end of the site.

Swinton site map.

Swinton Industrial School from the east, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Swinton Industrial School from the south-east, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1850, the Swinton school was the subject of the article A Day in a Pauper Palace in Charles Dickens' journal Household Words which reported that it was:

The stranger gazing upon the splendid brick edifice, with its surrounding territory, is surprised when he is told that it is not the seat of an ancient Dukedom ; but that it is a modern palace for pauper children. He is not surprised when he hears that it cost 60,000l.

Swinton, too, was visited by Poor Law Inspector Mr R.B. Cane in August 1866 and received a glowing report: "I believe the school to be an admirably well-managed establishment in every respect. It was in excellent order throughout."

At the 1881 census, the school had 799 inmates aged between 5 and 15, and 30 staff.

Swinton Industrial School from the south-east, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Like many establishments of its type, the school had a military-style boys' band.

Swinton Industrial School boys' band, 1920.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A report following an inspection of the school in around 1908 noted:

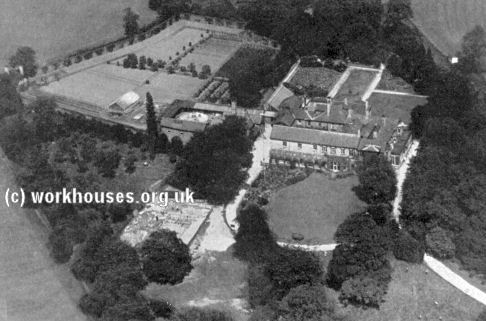

A subsidiary establishment known as the Swinton Home was later added at the west of the school site. It provided accommodation for mentally defective children and for those suffering from the after effects of "sleepy sickness".

Swinton Schools and Home (left) from the south-east, c.1929

© Peter Higginbotham.

The buildings on the main Swinton site were demolished in the 1930s and replaced by a new town hall. The Swinton Home was taken over by Manchester Corporation and continued in use as a 'mental home'. It joined the new National Health Service in 1948 as Swinton Hospital.

Rose Hill Home

In September 1915, the union acquired a property known as Rose Hill, on Longley Lane, Northenden. It was initially used as a residential school for children suffering from ophthalmia. It was later used as a children's convalescent home, housing up to 120 children. It subsequently became a residential nursery for the under-fives.

Manchester Rose Hill site, 1933.

Rose Hill home from the south-west, c.1929.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Tame Street Workhouse and Casual Wards

In 1897, the Manchester and Chorlton unions jointly set up a labour-test workhouse and casual ward at Tame Street, Ancoats, in a former cotton mill. The premises were rebuilt in around 1900 after being burnt down.

Manchester Tame Street site, 1905.

Manchester Tame Street casual wards and tower of administrative block from the south, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By the late 1920s, Tame Street was one of the largest casual wards in the country, with an average of 450 casuals sleeping there each night.

Langho Epileptic Colony

In 1906, again in collaboration with Chorlton union, Manchester set up a "colony" for the treatment of patients suffering from epilepsy. The colony was situated on a 166-acre estate at Langho in Ribblesdale, with its entrance on the Clitheroe to Preston Road.

Langho colony site, 1912.

Langho colony aerial view from the east.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Langho colony administrative block from the north-east, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Langho colony administrative block from the north-east, c.1929.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Residents were accommodated in a number of homes, each of which housed forty inmates.

A Langho colony patients' house, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A Langho colony patients' house, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Langho colony recreation hall, c.1907.

r

© Peter Higginbotham.

Langho colony hospital, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Langho site is now a mental health centre known as Kemple View and many of the original building are still in use.

Langho former colony patients' house, 2012.

r

© Peter Higginbotham.

Staff

- Manchester Crumpsall workhouse 1881 Census

- Manchester New Bridge Site 1881 Census

- Manchester Swinton Schools 1881 Census

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- Manchester Crumpsall workhouse 1881 Census

- Manchester New Bridge Site 1881 Census

- Manchester Swinton Schools 1881 Census

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Greater Manchester County Record Office (with Manchester Archives), Archives+, Manchester Central Library, St Peter's Square, Manchester M2 5PD. The few surviving holdings include: Workhouse admissions and discharges (1841-5); Creed registers (1881-1914, with gaps); Lists of children sent to Swinton Industrial School (1846-64); etc.

- Lancashire Record Office, Bow Lane, Preston, Lancashire, PR1 2RE. Swinton Industrial School admissions and discharges (1846-8, 1850-1934); indexes (1848-1935); etc.

- Find My Past has searchable Workhouse Registers (1800-1911).

Bibliography

- Ashton, J (1816) A Picture of Manchester

- Barclay, Jean (1989) Langho Colony/Langho Centre. 1906-1984: A Contextual Study of Manchester's Public Institution for People with Epilepsy

- Cook, John (2007) Swinton Industrial School: Manchester Union, Moral & Industrial Training School (Swinton & Pendlebury Local History Society)

- Greenwood, Mark (c.1998) Springfield Hospital

- Guest, AE (1961) Swinton Industrial Schools — A Historical Sketch and Personal Reminiscences.

- Prahms, Wendy (2006) Swinton Industrial School

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.