Workhouse Glossary

- Almshouse

An establishment, usually funded by a charitable endowment, providing free or subsidised accommodation for the elderly poor of good character, and typically constructed as a row of small self-contained cottages. A wealthy person might bequeath money for the setting up of some almshouses in the hope that the residents might then regularly pray for his soul. (See also Poorhouse, Workhouse.)

- Badging of the Poor

An Act of 1697, amending the Settlement laws, required that anyone receiving poor relief wear a badge on their right shoulder. The badge, in red or blue cloth, consisted of the letter "P" together with the initial letter of the parish, for example "AP" for Ampthill parish.

Pauper's badge for Ampthill parish

- Bastille (or Bastile, or "Old Basty")

-

A pejorative term for the workhouse, particularly associated with opponents of the New Poor Law, such as William Cobbett, in the 1830s-40s. As well implying an attack on the liberty of the poor, it probably reflecting the prison/fortress-like nature of some early workhouse designs. GR Wythen Baxter's 1841 book The Book of the Bastiles was a polemic against the post-1834 workhouse system. See also Grubber and Spike.

- Board of Guardians

The local management committee for each Poor Law Union. They were elected annually by the rate-payers in each parish in a Union. In addition, local magistrates could act as ex officio Guardians. The Board met at a fixed time either weekly or fortnightly, usually in a board-room at the workhouse.

- Boarding Out

Boarding out was the practice of placing workhouse children in the long-term care of foster parents who usually received a weekly allowance for each child staying with them. (See also scattered comes, cottage homes, children and education)

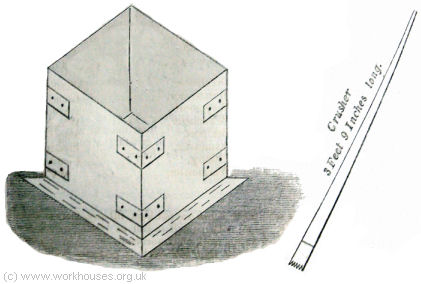

- Bone Crushing

The pounding of old bones into dust for use as fertilizer. In the 1840s, there was a public scandal when it was discovered that malnourished inmates at Andover workhouse had been fighting over scraps of rotting meat left on some bones they were supposed to be crushing.

Bone-crushing equipment, 1840s. © Peter Higginbotham.

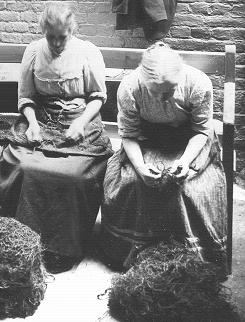

- Brabazon Scheme

The Brabazon Scheme was initiated in 1880 by Lady Brabazon who later became the Countess of Meath. It was intended to provide interesting and useful occupation such as knitting, embroidery or lace-making for non-able-bodied workhouse inmates who spent long hours confined to bed or in day rooms. Training in the various crafts was provided by outside volunteers and the costs were initially borne by Lady Brabazon. The scheme was slow to take off, with Kensington being the first to adopt it in 1883. However, it gradually spread, particularly when it was found that the goods produced were saleable and made the scheme self-financing. By 1897, there were over 100 branches.

- Bully's Acre

Originally the graveyard adjoining the Royal Hospital in Dublin, where no payment of fees was exacted. Later used more generally as an informal term for a paupers' or famine graveyard, especially associated with workhouse burial grounds. In recent years, there has been a growing campaign to protect bully's acre sites from redevelopment.

- Captain Swing Riots

In the autumn of 1830, agricultural labourers across southern England protested against low wages, expensive food, and the growing mechanization of farms. Threatening letters sent to land-owners and farmers were signed 'Swing' — the supposed, although probably fictitious, leader of the protests. Workhouses were amongst the rioters' targets — on 22nd November, a mob assailed the Selborne parish workhouse, turned out the occupants, burned or smashed the fittings and furniture, and pulled off the roof. The following day, an even larger mob, including the Selborne rioters, did the same to the workhouse at nearby Headley. The ringleaders were later transported to Australia. (See also Rebecca Riots.)

A typical 'Swing' letter. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Casual Poor ("Casuals")

The Casual Poor (usually known just as "Casuals") were those to which a workhouse gave temporary accommodation for one or two nights. Casuals — typically vagrants, tramps, or the "houseless poor" — did not need to be settled in the union. They were required to perform a task of work such as stone-breaking or oakum-picking being allowed to leave. Casuals were housed in a separate area of the workhouse, usually near the entrance, known as the casual ward.

- Casual Ward

Part of a workhouse for the accommodation of the casual poor. In London and a few other large cities, casual wards were sometimes erected on separate sites.

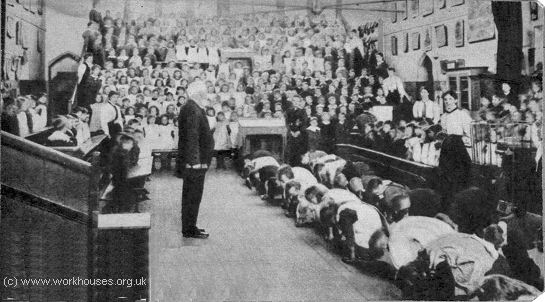

- Class Room

A smaller room in a school used for accommodating infants, or where a lesson was given to a particular class or group of pupils. A class room typically had three rows of seats around the outside all facing in to the centre, and was often fitted with a gallery containing further seats. (See also School Room.)

Children in a class-room - taking turns doing exercises for warmth in winter, c.1890. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Cottage Homes

Introduced in the late 1860s, and modelled on similar schemes in France, Germany and Switzerland, cottage homes were often set in rural locations away from the often poor conditions and malign influences of the union workhouse. Groups or "families" of pauper children lived in 'villages' of purpose-built houses often set along a street or around a green. Each house would have a house 'parent' looking after twenty or thirty children. (See also scattered homes, boarding out, children and education.)

Aston Union Cottage Homes. © Peter Higginbotham.

- County Home or County Institution

County Home or County Institution was another name for a Public Assistance Institution.

- Creed Register

From 1869, the workhouse master had to record the religious creed of each new inmate so that appropriate arrangements could be made in respect of their education (in the case of children), serious illness, or death.

Creed Register Form

- Dietary

The fixed (and often basic and monotonous) diet prescribed for workhouse inmates. The dietary specified the food to be served to each class of inmate (male/female, adult/children etc.) for each meal of the week, often including the exact amount to be provided. After 1834, the Poor Law Commissioners devised a set of six slightly different standard dietaries from which each union could select the one it preferred, based on the local availability of various foodstuffs. The "No. 3" diet is shown below.

- Earth Closet

A small outbuilding, room, or room-fitting used as a toilet, where dry earth is used to cover and deodorise deposits. (See also Privy, Water Closet, Water Closet, Lavatory, Laundry.)

Diagram of an earth-closet. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Ex Officio Guardians

Ex officio is a Latin phrase meaning "by virtue of one's office". Ex officio members of a union's Board of Guardians were people, usually local Justices of the Peace, who were entitled to a seat on their local Board without needing to be elected.

- Foul Wards

Workhouse wards for those suffering from venereal diseases.

- Grubber

-

One of the slang names for the workhouse, perhaps derived from grub — a slang term for food, or from a term used to describe a person who works hard, especially in a dull, plodding way. See alsoSpike and Bastille.

- Hospital

An establishment originally offering a wide range of care, not only medical but also non-medical provision such as shelter and food, the education of children, and sanctuary for those incapacitated by old age or chronic infirmity. (See also Infirmary.)

- House of Correction

An early form of disciplinary institution dating back to the 16th century. In addition to its function of a gaol for the rogue, it might also include a workhouse for the poor, hospital for the old, and industrial school for the young. Some small "lock-ups" were also called Houses of Correction - an example survives in Hawarden, Flintshire:

- House Of Industry

The name often used for the workhouse established by a Local Act Incorporations, also the "Hundred" institutions set up in Norfolk and Suffolk unions in the eighteenth century.

- Idiots and Imbeciles

Idiots and imbeciles were two commonly used categories of mental subnormality. Definitions varied over the years but in broad terms:

- Idiots, the most deficient, were unable to protect themselves against basic physical dangers.

- Imbeciles, a less severely deficient group, were unable to protect themselves against moral and mental dangers.

- Incorporation

A group of parishes joined by a special Local Act of Parliament and empowered to regulate a variety of local matters including poor relief.

- Indoor Relief

Poor relief provided via the workhouse. (See also Outdoor Relief.)

- Industrial Schools

Originally applied to workhouse schools where industrial training was given to pauper children. After 1856, the term was more commonly applied to schools set up to detain vagrant, destitute and disorderly children who were considered in danger of becoming criminals. From the 1930s, the latter were known as Approved Schools.

- Infirmary

An establishment offering treatment for the sick and injured, usually for a defined community. Thus, the medical provision in a workhouse was normally described as an infirmary. (See also Hospital.)

- Ins and Outs

"Ins and Outs" were people who frequently entered and left the workhouse. Workhouses were never prisons, and inmates could leave with "reasonable notice", so long as they had been given back their own clothes — leaving the premises while wearing the workhouse uniform constituted theft of union property. "Ins and Outs" were a great irritation to workhouse staff since, upon readmission, they had to undergo all the administrative formalities required of new inmates, even though they may have only been absent for a few hours. For an example, see the episode involving Charlie Chaplin's family at the Lambeth workhouse.

- Itch

"The Itch", or scabies, was a common medical condition caused by a small parasite, similar to lice, which burrows under the skin casuing severe itching. The conditiuon was often contracted through occupying a bed with an infected individual. Most workhouses had specially designated "itch wards" for such cases.

- Laundry

An out-building where newly washed clothes were processed, for example mangled, folded, pressed, ironed, starched etc. (See also Wash-house, Lavatory, Privy, Water Closet.)

- Lavatory

In workhouse times, a room in which inmates washed (as opposed to the modern usage meaning toilet). (See also Privy, Water Closet, Wash-house, Laundry.)

- Less Eligibility

The principle that conditions in the workhouse should never be better than those of "an independent labourer of the lowest class."

- Local Act

A special Act of Parliament granting a group or incorporation of parishes the powers to regulate local matters such as poor relief, lighting, watching etc.

- Lock Cases/Wards/Hospitals

"Lock" was a synonym for "venereal". Some large workhouses had a "lock ward" where those with venereal diseases (i.e. lock cases) were treated. (See also Foul Wards)

- Money

Prior to the decimalization of UK currency in 1971, a system of pounds, shillings and pence (£.s.d.) was in use:

- a pound was divided into twenty shillings, and the shilling was divided into twelve pennies (or pence) — there were thus 240 (20 times 12) pennies in a pound

- an amount such as fifteen shillings was usually written as 15s. or 15/-

- an amount such as fivepence was written as 5d. (the "d" originally stood for denarius — a small Roman coin); two shillings and nine-and-a-half pence was usually written as 2s.9½d. or 2/9½ — and read as "two and ninepence ha'penny"

- For some business purposes, a unit called the guinea (21/-) was used

- Coins in use included: the farthing (¼d), the half-penny or ha'penny, the penny, the threepenny bit, the sixpence, the shilling, the florin (2/-), the half-crown (2/6), the crown (5/-), and the sovereign (£1).

A Victorian half-penny and half-crown

(See also Workhouse Tokens, and Weights and Measures)

- Oakum / Oakum Picking

Oakum is the term for the loose fibres obtained by unpicking old ropes (known as 'junk') which were then sold to the navy or other ship-builders — it was mixed with tar and used for caulking (sealing the joints between planks of) wooden ships. It can perform a similar role for pipe joints in plumbing. Picking oakum was a task often given to workhouse inmates, especially vagrants in the casual ward who were required to pick a certain weight in a certain amount of time. It was done without tools and was very hard on the fingers. There is an interesting 1894 first-hand account which describes the task.

Picking oakum in the East End of London, 1906. © PRO (PRO 30/69/1663).

- Outdoor Labour Test

A provision whereby out-relief could be given to able-bodied applicants, in return for their performing manual labour such as stone-breaking. No more than half the relief could be given as money.

- Outdoor Relief (or Out-Relief)

Poor relief provided outside the workhouse, either in cash or in kind. (See also Indoor Relief)

- Out-relief Unions

Out-relief unions originated in 1873 as a result of a proposal by Local Government Inspector Andrew Doyle. He suggested that where parts of a union fell in different counties, the creation of an out-relief union within each county area could simplify the administration of out-relief and also allow different counties to adopt differing out-relief policies if they wished. The existing poor law union would still operate the workhouse for indoor relief across the whole union. Formal provision for out-relief unions came in section 58 of the 1888 Local Government Act and section 36(b) of the 1894 Local Government Act. Out-relief unions were formed on 28th December 1894 at Malton and Norton (bopth members of the Malton poor law union); Belvoir and Grantham (Grantham union); Bishopthorpe, Escrick, Flaxton and York (York union); and on 31st March 1895 at Keynsham and Warmley (Keynsham union).

- Overseers

Officials of a parish, between two and four in number, appointed by the Vestry. The duties of this unpaid post, first established in 1572, were primarily financial - to supervise the collection and distribution of the poor rate.

- Poorhouse

The term poorhouse was often used in England prior to 1834 for parish establishments housing paupers where there was no resident master or matron, no prescribed dietary, and where there little or no work was required of the inmates. Pauper establishments in Scotland were also invariably known as poorhouses (or poor's houses), perhaps reflecting that fact that they did not cater for the able-bodied and therefore imposed no requirement for deterrent work. However, the words poorhouse and workhouse were often used fairly interchangeably. After 1834, the institutions established by Poor Law Unions were always known as workhouses and always required the able-bodied inmates to perform work. In other countries, e.g. the USA, there was a similar distinction between the poorhouse (for the destitute, old and sick) and the workhouse (a place where hard labour was required of able-bodied paupers, including petty criminals serving a short sentence there). (See also Almshouse, Workhouse.)

- Poor Law Institution

The official name for a workhouse after 1912.

- Poor Rate

A compulsory local tax, dating from 1597, based on an official assessment of the value of the property in which one lived. It was collected by Parish Overseers and distributed under the jurisdiction of the Vestry.

- Privy

A room or small outbuilding used as a toilet, usually an earth closet rather than a water closet. (See also Privy, Water Closet, Earth Closet, Lavatory, Laundry.)

- Public Assistance Institution

After the formal abolition of the workhouse system in 1930, many former workhouses were redesignated as Public Assistance Institutions (PAIs). These establishments were administered by local Public Assistance Committees set up by county or county borough councils and were sometimes known as County Institutions or County Homes. PAIs provided accommodation for the elderly, chronic sick, single unmarried mothers and, in many cases, vagrants. The Institutions inherited many staff and inmates from the workhouse era and were not that different from their predecessors except that there were no uniforms, and the residents (rather than "inmates") could come and go as they pleased.

- Rebecca Riots

In 1842-3, the 'Rebecca Rioters' carried out a campaign of protests across South Wales which included the storming of the Carmarthen workhouse on the 19th June, 1843. The rioters took their name from the Book of Genesis (Chapter 24, Verse 60): "And they blessed Rebekah and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them." The rioters often included one or more 'Rebecca' figures dressed in women's clothes and wearing a wig of ringlets. (See also Captain Swing Riots.)

Rebecca rioters, 1843. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Removal

The process by which a person was returned to their parish of settlement from another parish where they had become a charge on the poor rates.

- Roundsman System

A system where parishes sent unemployed labourers around local ratepayers to be provided with work, with their wages being subsidised from the poor rate. An alternative version used a weekly auction of pauper labourers, again with their wages being raised to subsitence levels by the poor rates. The Roundsman System often operated in conjunction with the Speenhamland System

- Scattered Homes

Scattered Homes (or Isolated Homes) accommodated pauper children in ordinary houses, often rented for the purpose, which scattered around the suburbs of a town or city. Unlike cottage homes sites which usually had their own schools, the children in scattered homes attended ordinary local schools. (See also boarding out, children and education

- School Room

The largest room in a school where all the pupils could be accommodated at once. (See also Class Room.)

- Settlement

The principle by which a person could only claim poor relief from the parish under which they were officially "settled". Anyone trying to claim relief without correct settlement qualifications could undergo forcible removal to their own parish. A child's settlement at birth was taken to be the same as that of its father. Illegitimate children were granted settlement in the place they were born. If a boy became apprenticed his parish of settlement became the place of his apprenticeship. At marriage, a woman took on the same settlement as her husband. Settlement could also be acquired by various means such as renting a property above a certain value, or being continuously employed employed in a job for a year and a day.

- Skilly

A thin oatmeal soup or gruel - a regular part of the workhouse diet.

- Speenhamland System

A system named after the Berkshire parish where in 1795 local magistrates decided to supplement labourers' wages on a scale that varied with price of bread and number of children. It was formally expressed as follows:

When the gallon loaf of second flour weighing 8lb. 11oz. shall cost 1s., then every poor and industrious man shall have for his own support 3s. weekly, either produced by his own or his family's labour or an allowance from the poor rates, and for the support of his wife and every other of his family 1s. 6d. When the gallon loaf shall cost 1s.4d., then every poor and industrious man shall 3s. weekly for his own, and 1s.10d. for the support of every other of his family. And so in proportion as the price of bread rises or falls (that is to say) 3d. to the man and 1d. to every other of the family on every penny which the loaf rises above a shilling.Thus, if the price of bread rose to 1s.3d., a married man with two children would be guaranteed a wage of 3s.9d for himself plus three times 1s.9d., giving a total of 9 shillings a week.- Spike

One of the slang names for the workhouse (or more specifically its casual ward). Theories abound as to the origin of the word including:

- A short metal nail used in picking oakum.

- A large metal spike fixed in the ground or a rock and used for stone breaking.

- A small metal spike on which admission tickets (issued in some areas at local police stations) were placed after being handed over to the workhouse porter

- The "spiky" nature of the beds

- Spikes fixed to the top of the vagrants' yard wall to deter escape attempts.

- The pointed lightning conductors which adorned the roofs of workhouse buildings.

- Spike Island, near Cork, where convict gangs used to work. The men subsequently experienced similar treatment in workhouses and so began to refer to them as 'spikes'.

- The reference in Pickwick Papers (towards end of chapter XLI) to the Fleet Prison as 'Spike Park', a term said to have then been in common use among the inmates of the institution.

- A derivation of "spiniken", another tramps' name for a workhouse, originally based on "spinning house".

See also Bastille and Grubber.

Spikes in vagrants' yard wall at Ripon workhouse, 2000. © Peter Higginbotham.

Roof "spikes" at Bolton workhouse © Peter Higginbotham.

The entrance to Dunmow features a large iron (ornamental?) "spike".

Another workhouse "spike"? © Peter Higginbotham.

- Stone Breaking

A task sometimes performed by workhouse inmates, although most often used as a task for casuals or an outdoor labour test. Large blocks of stone had to be broken to pieces small enough to fit through a metal grid. The broken stones could then be sold for road-making.

Stone-breaking cell interior, c.1909. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Toke

A slang name for bread, often of poor quality.

- Treadmill

A large wooden wheel or drum with steps on its outside, generally used in prisons rather than workhouses. It rotated as inmates trod from one step to another - rather like the wheel in a hamster cage.

- Union

A grouping of adjacent parishes jointly administering poor law affairs. The "union" was one of the slang names for the workhouse.

- Vestry

The governing body of a parish. Its name derived from the room in a church building in which it usually met, which in turn came from its function as a room where the priest put on his vestments. Its membership comprised a chairman (the minister of the parish), the churchwardens, and a number of respected householders of the parish.

- Wash-house

An out-building where clothes were washed. (See also Privy, Water Closet, Lavatory, Laundry.)

- Water Closet

A small outbuilding, room, or sanitary-fitting used as a toilet, using water to flush deposits into a waste-pipe below. (See also Privy, Water Closet, Earth Closet, Lavatory, Laundry.)

- Wayfarers' Reception Centre

The official name for a casual ward after 1930.

- Way-Ticket

A certificate issued by a casual ward or police-station to casuals judged to be the "honest unemployed" giving them preferential admission or treatment at a workhouse casual ward.

- Workhouse Test

The principle by which a pauper would only be granted poor relief through being admitted to a workhouse and being prepared to accept the terms of its harsh regime.

- Weights and Measures

During the workhouse era in Britain, the "Imperial" system of weights and measures was in use as shown below, together with metric equivalents:

-

Weight

16 drams or drachms (dr.) = 1 ounce (oz.) = 28.35 grams 16 ounces (oz.) = 1 pound (lb.) = 454 grams 14 pounds (lbs.) = 1 stone = 6.35 kilograms 8 stones = 1 hundredweight (cwt.) = 50.8 kilograms 20 hundredweights = 1 ton = 1.016 tonnes

-

Length

12 inches (ins.) = 1 foot (ft.) = 30.48 centimetres 3 feet (ft.) = 1 yard = 0.91 metres 1760 yards = 1 mile (ml.) = 1.61 kilometres

-

Capacity

4 gills = 1 pint = 0.568 litres 2 pints = 1 quart = 1.136 litres 4 quarts = 1 gallon = 4.546 litres

-

Weight

- Workhouse

An establishment offering relief for the destitute poor in an area, funded from the local poor rate, which — under the supervision of a Master and/or Matron — provided some combination of communal accommodation and a requirement for inmates, particularly the able-bodied, to perform work which was often deterrent in nature, e.g. stone-breaking or oakum-picking. Workhouses usually also had a prescribed dietary. (See also Poorhouse, Almshouse.)

- Workhouse Tokens

In the early 1800s, there was a national shortage of coins caused by scarcity of copper and silver. To help keep local commerce operating, a number of organisations minted tokens in denominations such as 1d., 3d, 6d. and one shilling. Several workhouse authorities issued such tokens as poor-relief and paupers could use them to buy bread etc. Traders who received the tokens could then periodically redeem them at the workhouse. In 1817, such tokens were declared illegal although a temporary exception was made for those for the Birmingham and Sheffield workhouses. The first example below, from 1812, features a picture of the Birmingham workhouse, and the wording "ONE POUND NOTE PAYABLE AT THE WORKHOUSE FOR 240 TOKENS"

Birmingham workhouse token. © Peter Higginbotham.

Another example, also from 1812, was manufactured in Birmingham for use by the Bradford workhouse.

Bradford workhouse token. © Peter Higginbotham.

Here is an 1813 penny token minted for the Halesowen Workhouse.

Halesowen workhouse token. © Peter Higginbotham.

Finally, here is silver shilling token issued by the Leeds workhouse in 1812.

Leeds silver shilling workhouse token. © Peter Higginbotham.

Tokens were also issued during the same period at Tunstead & Happing in Norfolk, and at Worcester.

For more information on early 19th century tokens, see British Copper Tokens 1811-1820 by P.J.Withers, (1999, Llanfyllin, Powys: Galata Print Ltd.)

In the late 1800s, the Social Wing of the Salvation Army made use of tokens, for example for paying men working at its "Elevator" factories.

Salvation Army 4d Token. © Peter Higginbotham.

- Workhouse Visiting Society

Organization founded in 1858 by Louisa Twining. Its aims were "the promotion of the moral and spiritual improvement of Workhouse inmates" - especially "destitute and orphan children", "the sick and afflicted" and "the ignorant and depraved". The Society published a Journal from January 1859 until 1865.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.