Workhouse Architecture

Early Workhouses

An assortment of workhouse establishments was set up in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Some of these were in the City of London in the 1650s, some were in textile-manufacturing towns, for example the Oracle in 1628 at Reading, and a small number were in provincial towns such as Chichester where, in 1681, some former almshouses were adapted for use as a workhouse.

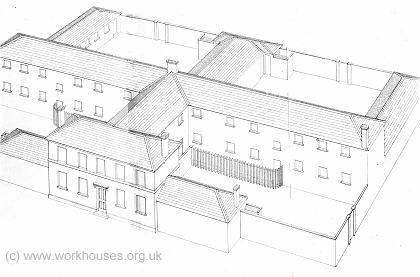

Chichester workhouse, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

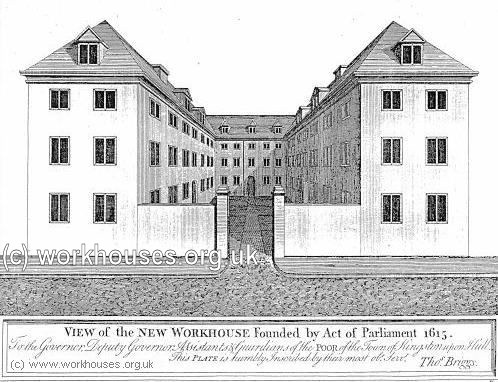

Many of these early institutions were 'working-houses' — places where work was performed by the poor unemployed — and did not necessarily provide any of the residential accommodation or medical care facilities etc. that later became associated with workhouses. These early establishments were usually established in existing buildings rented by the parish or town, rather than being purpose-built. Early examples of a building erected specifically as a workhouse are the Charity Hall in Kingston-upon-Hull erected in 1698 and the Exeter Incorporation workhouse of 1701. Hull's workhouse was a U-shaped three-storey structure with attics and was said to comprise "about forty-five rooms, wards, garrets, lobbies, school and dining-rooms, workrooms, etc."

Hull workhouse, 1789.

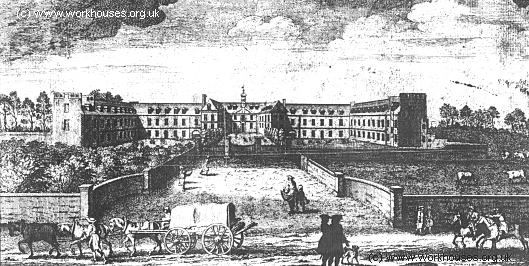

Exeter's 1701 workhouse had in fact been preceded in the 1670s by an even earlier purpose-designed building about which little is known. However, new building accommodated around 200 inmates in a classical-style structure which included inmates' accommodation, a central chapel, and workshops.

Exeter, 1744, by R White from Rocque's 1744 Map of Exeter.

The Eighteenth Century

The passing of Knatchbull's Act in 1723 led to a large increase in the number of parish workhouses being established. Although many of these were set up in existing buildings, a number were purpose-built such as those at Lingfield (1729), Walthamstow (1730), Cudham (1731) and Horncastle (1735). In style, however, these new buildings often resembled the housing of the locality.

Walthamstow 1730 parish workhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Horncastle 1735 parish workhouse.

© Simon Meeds.

Many workhouse buildings on a much larger scale appeared in the latter part of the eighteenth century with the creation of a substantial number of local Act incorporations. Many of these were in East Anglia, such as Samford (1764) and Stow (1778). These were often substantial U or H-shaped buildings, more on the scale of local manor houses.

Samford from the south-east.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Stow main building from the south.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Example of other incorporation "Houses of Industry" from this period include the Isle of Wight (1770) and Montgomery and Pool (1792).

Isle of Wight 1770 House of Industry.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Montgomery and Pool 1792 House of Industry.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Another impetus to the building of workhouses came with Gilbert's Act of 1782 which allowed parishes to combine into a union and erect a workhouse. Almost a hundred widely assorted workhouse were erected by Gilbert Unions, example of which include Brinton and Melton Constable (1783), Hambledon (1786), Headley (1795).

Brinton and Melton Constable 1783 workhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hambledon 1786 workhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Headley 1795 House of Industry.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Early Nineteenth Century

The early nineteenth century saw architectural developments that were to become significant in workhouse design. One of these was the supervisory hub whose position and shape provided views over all the inmates' exercise yards. Early examples of this are found at Caistor (1800) and Ongar (1830).

Ongar rear main block with central supervisory hub.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Another development was increasingly strict segregation of different classes of inmate, not just of male from female, but also of the aged and infirm from the able-bodied poor. This principle was most clearly demonstrated in workhouses such as the one at Southwell erected in 1824 by the Thurgarton Hundred, established under Gilbert's Act. Males and female accommodation was separated by the central supervisory hub. Within each side, the accommodation was strictly divided between that for the "guiltless" poor and the "idle, immoral, and improvident" able-bodied".

Thurgarton Hundred 1824 workhouse main block.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1834

The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act required the whole of England and Wales to be divided into Poor Law Unions each with its own general workhouse. In the following five years, around three hundred and fifty new Union workhouses were erected. In other Unions, workhouses were established by major upgrades to existing parish workhouse buildings.

Union workhouses had to embody the principles of classification, segregation and supervision, and the layout of buildings such as that at Southwell were influential in shaping new designs. In 1835 and 1836, the Poor Law Commissioners published model workhouse plans intended for a variety of situations.

The Courtyard Plan

One of the model workhouse designs was the "courtyard" plan for rural unions devised by one of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioners, Sir Francis Head. In this layout, the buildings were arranged around three sides of a large quadrangle. The inmates' accommodation was arranged on two storeys and consisted of a large number of small dormitories, each around 15 feet by 10 feet, roughly based on the size of a typical poor labourer's cottage. Each dormitory was intended to accommodate 8 inmates in four double beds. The dormitories on the upper floor were reached by external iron staircases. The large inner courtyard was divided by a twelve-foot high wall dividing the male and female sides. A single lavatory or privy was provided on each floor on each side of the workhouse. The administrative offices, board-room, Master's quarters, kitchens, dining-halls, store-rooms, washhouse etc. were placed on two floors at either side of the entrance archway on the fourth side of the quadrangle.

Sir Francis Head's 1835 Courtyard Plan, ground floor.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Head was the Assistant Commissioner responsible for overseeing the formation of the new Poor Law Unions in Kent, and his plans was adopted by twelve of these: East Ashford, West Ashford, Blean, Bridge, Dover, Eastry, Elham, Faversham, Hoo, Maidstone, Milton Regis, and the Isle of Thanet. Head did not himself design these individual workhouses, but each union appointed a surveyor to produce detailed plans based on the model design. At the end of 1835, Head left the Commission to take up an appointment as Lieutenant-General of Canada.

Entrance block of Head's courtyard design at Bridge.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Inmates' dormitories in Head's courtyard design at Bridge, with remains of courtyard dividing wall.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A number of problems emerged with Head's courtyard plan. It lacked a chapel, sick-room, and lying-in room. The original layout of the rooms in the entrance block proved unsatisfactory, Extra diagonal dividing walls were needed to segregate all the various classes of inmate, and extra privies and fireplaces had to be added.

Head's plan was not adopted elsewhere, although courtyard-style designs were produced by William T Nash for workhouses at Buntingford, Caxton and Arrington, Halstead, Royston, and St Ives.

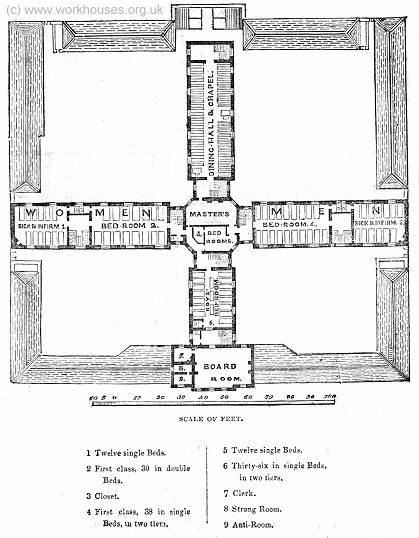

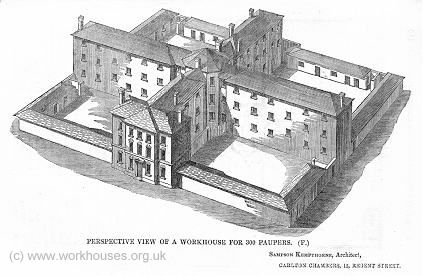

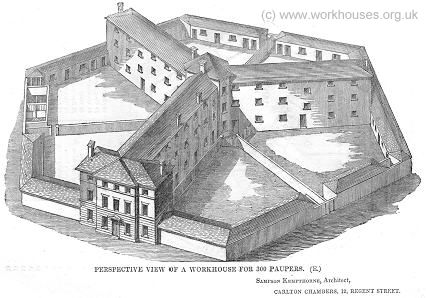

The Square Plan

The most widely adopted of the model plans were those produced by the architect Sampson Kempthorne. His cruciform or "square" design featured an administrative block at the front containing a porter's room and waiting-room on the ground floor, with Guardians' board-room above. At the rear, a children's block linked to the supervisory octagonal hub where the Master's quarters lay. Male and female quarters emanated to the left and right of the hub, while kitchens and stores with dining-hall above stood in the wing at the rear. The square perimeter of the building comprised single storey workshop and utility blocks which also served to enclose the various inmates' exercise yards. Each of the four areas was often divided by walls into two, allowing up to eight segregated exercise areas. Square-plan workhouse typically accommodated between 300 and 500 inmates.

Kempthorne's 1835 "square" plan , ground floor.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Kempthorne's 1835 "square" plan, first floor.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Kempthorne's 1835 "square" plan in perspective.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Although the square plan was widely used and adapted by others, Kempthorne himself designed around ten square-plan workhouses including those at: Andover, Axminster, Barnstaple, Basingstoke, Eton, Hastings, Mansfield, Market Harborough, Newbury, and Wantage.

Eton workhouse by Sampson Kempthorne.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eton workhouse by Sampson Kempthorne.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eton workhouse by Sampson Kempthorne.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Hexagonal or "Y" Plan

Kempthorne's hexagonal or "Y-plan" design was essentially a variation of the square plan, with three radiating wings rather than four, and with a hexagonal central hub and perimeter.

The first new workhouse to be erected under the 1834 Act was the hexagonal workhouse at Abingdon for which Kempthorne himself was the architect.

Kempthorne's 1835 "hexagonal" plan in perspective.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Other hexagonal designs included those at Banbury, Bath, Bradfield, Bridgwater, Chertsey, Crediton, Droxford, Frome, Grantham, New Forest, St Thomas, Taunton, Ticehurst, Warminster, and Yeovil.

Frome workhouse by Sampson Kempthorne.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Crediton workhouse by Sampson Kempthorne.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The 200-Pauper Plan

In 1836, Kempthorne produced a cut-down version of the square plan which was known as the '200-pauper' plan and lacked a polygonal supervisory hub. It was intended for use in more rural areas where pauper numbers were lower.

Kempthorne's 1835 200-Pauper, ground floor.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Kempthorne's 1836 200-Pauper plan in perspective.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Examples of the 200-pauper plan were Kempthorne's design for Droitwich, Huntingdon, Lymington, Martley, Okehampton, Orsett, Pershore, South Molton, Thornbury, Torrington, Upton-upon-Severn, and Winchcomb.

Kempthorne's 200-Pauper design at Lymington.

© Peter Higginbotham.

George Wilkinson

Kempthorne's model plans were also adopted by another significant figure in workhouse architecture, George Wilkinson. Wilkinson's first professional commission was for the workhouse in his home town of Witney in Oxfordshire. He was then responsible for over 20 early workhouse designs in England and Wales. Most of these (Abergavenny, Bridgend, Bromyard, Chard, Cricklade and Wootton Bassett, Devizes, Dorchester, Gainsborough, Honiton, Ledbury, Northleach, Pembroke, Stow-on-the-Wold, Weobley, and Wincanton) adopted the popular square plan. Three others (Chipping Norton, Witney and Wolverhampton) employed a novel St Andrews Cross variation of the square plan. A few others (Aberayron, Malmesbury, Thame and Woodstock) had non-standard plans.

Weobley's square layout.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Witney' St Andrew's Cross layout.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1839, impressed by his work, the Poor Law Commissioners offered Wilkinson the mammoth job of designing all the workhouses in the 130 newly created 130 unions in Ireland. These were all based on variations of a standard plan and executed in Wilkinson's favoured plain Tudor style though with costs kept to a minimum, for example with earthen floors in the dayrooms since most of the occupants it was assumed "will be without shoes and stockings".

Swineford workhouse entrance block, County Mayo.

© Peter Higginbotham.

George Gilbert Scott and William Bonython Moffatt

George Gilbert Scott was originally employed as an assistant by Sampson Kempthorne. However, Scott soon set up on his own and took on William Bonython Moffatt as his assistant and later partner.

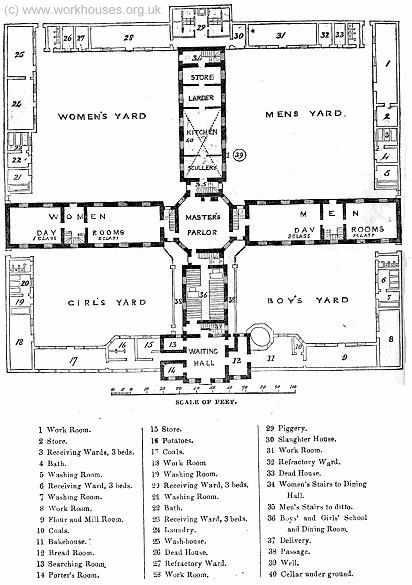

Over the next 10 years Scott and Moffatt designed over 40 workhouses, many of which followed a distinctive layout evolved by Scott. This plan was derived from Kempthorne's square plan, but with the front-facing arm of the central cross removed. Instead, a long single-storey range placed at the front contained the porter's lodge, board room, receiving wards and chapel. A central entrance archway led through to an inner courtyard either side of which were boys' and girls' yards. The main building still retained a central hub containing the master's offices and quarters. To each side were male and female day rooms and dining halls on the ground floor, with dormitories above. The rear range contained kitchens and scullery. Behind were workrooms, laundry, bakehouse etc. with an infirmary block at the rear. The large scale OS map of Guildford workhouse is typical variation of this design.

Guildford workhouse site, 1868.

The earlier buildings of this type were in a simple Classical style. Unions that adopted this design include: Bideford, Boston, Guildford, Horncastle, Liskeard, Louth, Newton Abbot, Penzance, Redruth, Spilsby, St Austell, St Columb Major, Tavistock, Tiverton, Williton, and Witham.

Witham union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Witham union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Scott and Moffatt's later work shows an increasingly rich style with a preference for neo-Elizabethan and neo-Jacobean designs, for example as at Dunmow in 1838 and Windsor in 1839.

Dunmow union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Windsor union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Corridor Plan Workhouses

Between about 1840 and 1870, new workhouse buildings moved away from the PLC's model radial plans. Influenced by Scott and Moffatt's designs, it became the norm to have a separate entrance block, linear main block, and hospital block all running parallel to one another. The main block generally had a central corridor along its length with rooms off to both sides, unlike the earlier designs which were usually one room deep. The main block normally had the administrative functions at its centre, perhaps surmounted by a tower containing a large water tank, and with kitchens and dining hall to the rear, creating a building that was T-shaped. Many of the new buildings of this type were in the north of England, which had initially held out against building new workhouses, and in London where pre-1834 buildings had continued in use but had become too cramped. Around 150 corridor-plan workhouses were built in the period 1840-70. The style of the buildings was often Italianate, with gables, pinnacles, projecting bays, and Venetian windows. Amongst the many examples are Warrington (1849), City Of London (1849), Bolton (1858), Preston (1865), Rochdale (1873).

Warrington union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

City Of London union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bolton union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Preston union workhouse

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rochdale union workhouse

Courtesy of Rochdale NHS Trust.

Pavilion Block Workhouses

From 1870 onwards, the trend in workhouse building was increasingly towards accommodating inmates of a particular category or condition in separate blocks or pavilions linked by covered walkways. This change coincided with widespread attempts to improve sanitary conditions and reduce the spread of disease which was thought to be largely airborne.

One of the earliest pavilion plan designs was used by the Chorlton union for its new infirmary, built in 1864-6 and designed by Thomas Worthington. It comprised five well-spaced ward blocks, each accommodating 96 patients and linked by a covered way.

Chorlton union infirmary

© Peter Higginbotham.

What became known as "Nightingale wards" were characterized by long wards with pairs of opposing windows allowing a through draught. Beds, of which the optimum number was decreed to be 32 per ward, were placed singly or in pairs between the windows. Sanitary facilities were placed in towers attached to the outer ends of wards, accessed by a cross-ventilated stem.

The first workhouse built on a pavilion plan was at Madeley in Shropshire, erected in 1871-5. It comprised a central single-storey block containing dining-hall and kitchen which was linked by covered ways to the two-storey accommodation blocks. Other separate blocks included an infirmary, isolation block, entrance block, and workshops.

Madeley workhouse site, 1901.

Madeley accommodation and central dining/kitchen blocks

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bibliography

- Morrison, Kathryn The Workhouse, English Heritage, 1999.

- Cole, David (1980) The Work of Sir Gilbert Scott, The Architectural Press, London.

- Dickens, AM (1976) The Architect and the Workhouse, Architectural review, CLX, No. 958, 345-52.

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.