The Metropolitan Asylums Board

Between 1867 and 1930, the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB) played a substantial and increasing role in the care of London's sick poor. During that period, institutional medical care for the poor was transformed from a system based on often squalid workhouse infirmaries, staffed by illiterate paupers, to one which included around forty general and specialist MAB establishments, many purpose-built, staffed by well-trained personnel. The institutions set up by the MAB came to be accessible by all the capital's inhabitants, not just the poor. The Board can justly claim to have provided the nation's first state hospitals, and laid the foundations of what in 1948 became the National Health Service.

Origins of the Board

The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, and the report of Royal Report that shaped it, were preoccupied with the able-bodied poor. Originally, the Report had proposed distinct institutions for different categories of pauper inmate: 'At least four classes are necessary:— 1. The aged and really impotent; 2. The children; 3. The able-bodied females; 4. The able-bodied males.' However, it did not clarify the meaning of the term 'impotent' or suggest any alternative to the existing practice of providing the sick poor with relief in their own homes. For a number of reasons, such as ease of management and financial saving, the general mixed workhouse soon became adopted as the norm for the new system. Thus, a single establishment had to try and provide both a severe deterrent regime for the able-bodied, and also to do what it could to accommodate the sick and aged who increasingly figured amongst its inmates.

Although Unions were required to appoint a workhouse medical officer, these were often part-time and badly paid. Furthermore, medical officers normally had to pay for the cost of any drugs they used out of their own salary. Nursing in workhouses was usually done by elderly and illiterate inmates. In 1866, a total of 21,000 sick and aged inmates in London workhouses were being cared for by a nursing staff that included only 142 paid non-pauper nurses, very few of whom had received any hospital training.

By the 1850s, critics of the workhouse system, and in particular its provision for the sick, set up the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS). At its inaugural conference in 1857, Louisa Twining read a paper recounting her experiences visiting the Strand and other London workhouses, and witnessing the poor conditions there. As a result, the Workhouse Visiting Society was formed the following year and campaigned for improvements in the treatment of the sick poor. This, together with the severe strain placed on many workhouses by the severe winter of 1860-61, led to the appointment in 1861 of a Parliamentary Select Committee to investigate the state of the poor relief system. Its report, presented in 1864, recommended only one change to medical relief in the workhouse. This was that the cost of 'cod liver oil, quinine and other expensive medicines' would be met by the guardians rather than by medical officers, a measure resulting from the testimony of Dr Joseph Rogers, medical officer of the Strand Union.

In December 1864, much publicity was given to the death of an Irish navvy, named Timothy Daly, from gross neglect in Holborn workhouse. As a result of this, Florence Nightingale began a campaign for nursing reform in workhouse infirmaries. In January, 1865, she contacted Poor Law Board President, Charles Villiers, and in conjunction with the Board's inspector Mr HB Farnall, drew up a 'Form of Enquiry' for use in investigating every London workhouse and sick ward. Villiers also sent out a circular to metropolitan Boards of Guardians calling on them to discontinue the use of untrained inmates for attending the sick, and instead to appoint trained nurses. However, this suggestion did not have the status of an official Order so had little immediate effect.

Florence Nightingale

A few months later, in July 1865, the medical journal The Lancet began publishing a series of detailed reports about the state of London workhouses. The articles were compiled by Mr Ernest Hart, a physician attached to the staff of the Lancet, Dr Anstie, from the staff of the Westminster Hospital, and Dr Carr, a poor law medical officer from Blackheath. Their accounts painted a relentless picture of insanitary conditions, inadequate ventilation, poor nursing, defective equipment, and overcrowding. A subsequent interview with Matilda Beeton, a former nurse at the Rotherhithe workhouse infirmary, revealed that 'many sick patients were dirty, and that their bodies crawling with vermin'; sheets were changed once in three weeks and soiled sheets had to be washed in the infirmary at night; there was 'a bad supply of towels used for every clean and dirty purpose'; beds were made of flock and 'maggots would crawl from them by hundreds'; the 'sick diet was a mockery — milk was not heard of'. Similar conditions were alleged at the Strand and Paddington workhouses.

In 1866, Drs. Hart, Anstie and Rogers, with the support of prominent figures such as Charles Dickens, set up The Association for Improvement of the Infirmaries of London Workhouses whose aims included the setting up of six thousand-bed poor law hospitals in London staffed by trained nurses, resident medical officers, and medicines financed from the rates. Meanwhile, Florence Nightingale had approached the Prime Minister and old family friend, Lord Palmerston, who encouraged her to draft a bill encapsulating her recommendations. Unfortunately, Palmerston died in October 1865, and in December she went back to Charles Villiers with her proposals. Her ABC of Workhouse Reform contained three main principles:

- That the sick, insane, incurable and children should be dealt with in appropriate and separate institutions.

- That medical relief in London should be under a single central management.

- That the system should be financed by 'consolidation and a general rate', not from parish rates.

Villiers entirely supported her aims and agreed to press for a new London Poor Law Bill. He also instigated a new enquiry into the care of the sick in London workhouses, undertaken by his two poor law Inspectors, HB Farnall and Edward Smith. However, Villiers felt that the weak state of the Whig Government in the spring of 1866 made it an inopportune time for proposing new legislation upon such a controversial subject.

In June 1866, the Whig government fell and was succeeded by a Tory administration with Lord Derby as Prime Minister. Mr Gathorne Hardy, a former poor law guardian, was appointed the new President of the Poor Law Board and was immediately contacted by Florence Nightingale with details of her reform scheme. Hardy, however, appears to have had little interest in her proposals and thought that no new legislation was required to remedy the situation in London's workhouses. He also took no action on the recently completed survey by Inspectors Farnall and Smith. Instead, he appointed two new Inspectors to the metropolitan area, Dr WO Markham, former editor of the British Medical Journal, and Mr Uvedale Corbett, an experienced poor law inspector. Their report, which contained statistical studies of the diseases and accommodation of the non-able-bodied poor, recommended the creation of separate hospitals for the sick poor, and dispensaries for the outdoor poor.

Gathorne Hardy also consulted the President of the Royal College of Physicians, Sir Thomas Watson, who convened a committee to examine workhouse medical provision in the capital. Their extensive report included detailed recommendations on infirmary construction, ventilation, and the space requirements for different classes of patient, together with proposals for nursing reform in an appendix contributed by Florence Nightingale. The Watson Committee urged that the sick poor should be treated in separate accommodation, and that the insane and those suffering from infectious fevers and smallpox should be placed in specially erected hospitals.

Early in 1867, Gathorne Hardy began drafting a new poor law bill. On 6th February, the government announced its intention to introduce a measure 'for improving the management of sick and other poor in the metropolis'. The Metropolitan Poor Act, which was passed by parliament on 14th March, 1867, was 'for the Establishment in the Metropolis of Asylums for the Sick, Insane, and other Classes of the Poor, and of Dispensaries; and for the Distribution over the Metropolis of Portions of the Charge for Poor relief; and for Other Purposes relating to Poor relief in the Metropolis.' The Bill empowered the Poor Law Board to combine London's unions and parishes into Districts, and to raise contributions from them for a Common Poor Fund, from which they could reclaim the costs of all drugs, medical appliance, and the salaries of all poor relief officers. The Fund would also be used to finance new hospitals and the maintenance of patients being treated in them. The Act also abolished the Local Act status of many of London's parishes, which had allowed them to escape most of the strictures of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

Six weeks after the Bill received its Royal Assent, Gathorne Hardy announced that for the purposes of dealing with the sick poor suffering from smallpox, fever, or insanity, all London's unions and parishes would be combined to form the Metropolitan Asylum District. This was to be overseen by a new body — the Metropolitan Asylums Board, whose management board was to comprise 45 elected Guardians and 15 appointed members. At its first meeting on 22nd June, 1867, Dr William Henry Brewer was appointed as the Board's Chairman.

The Sick Asylum Districts

In 1868, as a separate strand to the implementation of the Metropolitan Poor Act, the Poor Law Board formed six new 'Sick Asylum Districts' which were to erect joint 'asylums' or hospitals for dealing with the general sick poor. The Districts created were:

- Poplar and Stepney SAD — comprising the Poplar and Stepney Unions

- Central London SAD — comprising the Westminster and Strand Unions and the parishes of St Giles-in-the-Fields and St George, Bloomsbury

- Rotherhithe SAD — comprising the St Olave Union and the parishes of St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey, and St Mary, Rotherhithe

- Newington SAD — comprising the St Saviour Union, and the parishes of St George the Martyr, Southwark, and St Mary, Newington

- Finsbury SAD — comprising the Holborn Union and the parishes of St James, Clerkenwell and St Luke, Middlesex

- Kensington SAD — comprising the parishes of St Margaret and St John, Westminster, and St Mary Abbots, Kensington

Concerns about the high costs of building the proposed large new hospitals, estimated to be £45,000 to £50,000 each, led the Poor Law Board to reconsider the scheme. Under its revised plans, two of the new Districts survived — the Poplar and Stepney and the Central London Districts. Three other Districts were reconstituted as enlarged poor law unions (namely St Olave, St Saviour's, and Holborn). The Kensington District was dissolved and St Margaret and St John joined St George, Hanover Square to form the new St George's Union. The new unions, like all the other London unions not included in the surviving Sick Asylum Districts, were required to provide hospitals on sites separate from their workhouses. They would do this by redeploying and adapting existing premises, and where necessary, by erecting new buildings.

The Early Work of the MAB

The MAB immediately began to make plans for the erection of its own hospitals which would provide care for cases of smallpox, fever or insanity, and which would be easily accessible from all parts of the city. They eventually identified three sites — at Hampstead in the north-west, Homerton in the north-east, and Stockwell in the south-west — on each of which it was intended to build a 200-bed fever hospital and 100-bed smallpox hospital. The hospital at Hampstead was delayed by some local opposition to the scheme which involved Sir Rowland Hill, pioneer of the postage stamp, who owned an adjacent property. However, construction work at the other sites began in 1869.

At the end of 1869, before the new hospitals were ready, there was an outbreak of relapsing fever (an infection transmitted by ticks or lice) in the east of London. To deal with this, the MAB erected temporary huts in the grounds of the London Fever Hospital at Islington and at its Hampstead site. The facilities at Hampstead consisted of timber and metal huts providing 90 beds, and designed with the possibility of being enlarged to 180 beds. The site, which opened on 25th January, 1870, was effectively England's first state hospital. It closed after the fever epidemic subsided in May 1870, but re-opened in December 1870 when there was a serious outbreak smallpox in London.

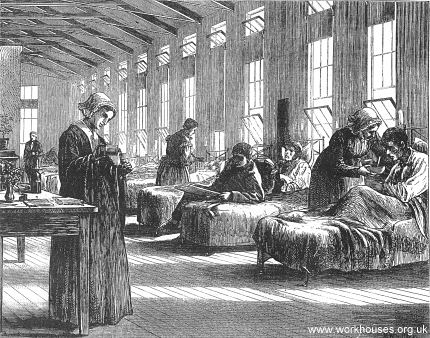

Hampstead ward interior, 1872

The two other new smallpox and fever hospitals opened shortly afterwards — the South-Western Hospital at Stockwell on 31st January 1871, and the Eastern Hospital at Homerton a few weeks later on 26th February. A hospital ship, the Dreadnought moored off Greenwich was also chartered from the Admiralty and used for convalescent patients.

To deal with mental cases (what were then labelled as 'imbeciles', 'idiots', and 'lunatics'), the Board chose two locations — one north of the Thames at Leavesden in Hertfordshire, the other at Caterham in Surrey. In 1869, work began at the two sites on the construction of large asylums each of which would accommodate around 1,500 patients. The Leavesden and Caterham imbecile asylums opened within a few weeks of each other in the autumn of 1870. Initially, it was intended that these asylums should only handle paupers having a medical certificate to the effect that they were 'a chronic and harmless lunatic, idiot or imbecile'. However, both institutions were soon filled with a wide variety of conditions, acute and chronic, and with patients of all ages. From 1873, it was decided that imbecile children should be housed separately from adults and they were initially placed at now empty Hampstead hospital. Teachers were appointed in a novel experiment to try educating 'idiot' children.

Leavesden Asylum, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham

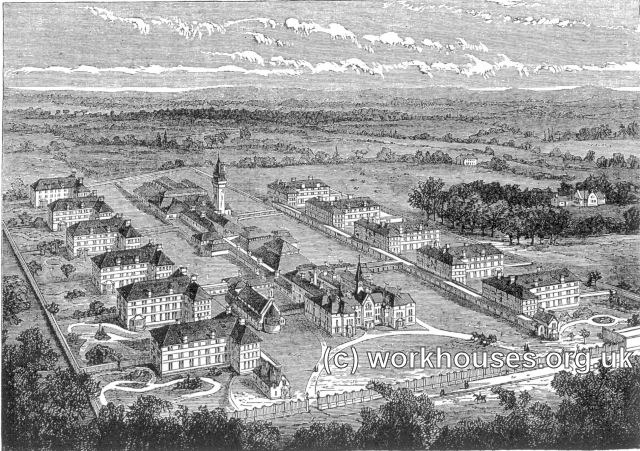

Caterham Asylum, 1872

To prepare for further fever epidemics, two new sites were acquired near the Old Kent Road in Deptford, and at West Brompton in Fulham. In 1875, it was decided to begin construction of what respectively became the Deptford Hospital and Fulham Hospital. Work also began on a new permanent school for imbecile children at Darenth near Dartford in Kent.

The Response to Smallpox

There was a lull in smallpox outbreaks until 1876 when a major new epidemic soon outstripped all the available accommodation. Hampstead resumed operation as a smallpox hospital and its imbecile children moved to temporary premises until the new children's asylum at Darenth was finished. Work on the new hospitals at Deptford and Fulham was speeded up and both were opened in March 1877.

In January 1879, Sir Rowland Hill and other Hampstead residents living near the Hampstead Hospital were granted a legal injunction against the MAB who were required to "stop carrying on the hospital so as to cause a nuisance". Legal wrangling continued until 1883 until the MAB finally made an out of court agreement limiting the number of smallpox patients patients in the hospital at any one time to forty, and moving the hospital's entrance.

A brief article in The Times on 22nd December, 1880, during another major smallpox outbreak, further increased public anxieties.

—"The reopening of the Homerton Hospital for small-pox patients has been followed, as was the case in both previous epidemics at Hampstead, by a serious outbreak of the disease in the surrounding houses, thus furnishing further proof that the present large hospitals instituted by the Asylums Board are a source of serious danger to the surrounding population.

At Fulham, local residents applied for an injunction to prevent smallpox cases being placed at the Fulham Hospital. A compromise was reached whereby only cases discovered within a one-mile radius of the hospital would be admitted. A detailed study of the spread of smallpox cases in the Fulham area was made by Local Government Board Inspector Dr WH Power. He concluded that the incidence of cases within a one mile radius of the Fulham Hospital was up to four times as great as in other parts of the adjoining districts.

In the meantime, to deal with the continuing shortage of beds, the MAB again resorted to chartering two old wooden battleships, the Atlas and the Endymion. These were adapted at a cost of £11,000 and moored at Greenwich. A tented camp was also established on land adjacent to the Darenth asylum. In May, 1881, London's first ambulance service came into existence when hired horse-drawn ambulances were used to convey patients from Deptford Hospital to the canvas hospital at Darenth — the eighteen-mile journey took three hours.

In response to the growing concerns about the treatment of smallpox, a Royal Commission was appointed in 1881 to examine the arrangements for dealing with infectious diseases in the capital. In its report the following year, it recommended that the provision of medical facilities for such cases be disconnected from the Poor Law and treated as part of the sanitary arrangements for the metropolis. It also proposed that smallpox cases be treated in isolated hospitals on the banks of the Thames or in floating hospitals on the river itself. In addition, convalescent hospitals were to be established at some distance in the country. Finally, a central ambulance service should be established. In 1884, the existing smallpox hospitals became primarily fever hospitals with Deptford Hospital being renamed the South Eastern Hospital, and Fulham Hospital being renamed the Western Hospital. The hospital ships Atlas and Endymion were moved to new moorings at Long Reach near Dartford, 15 miles below London Bridge. They were joined by a third vessel, the Castalia, a former passenger ferry. In 1890, a new permanent convalescent hospital, the Southern, was built on the Gore Farm estate near Dartford, adjoining the tented camp at Darenth.

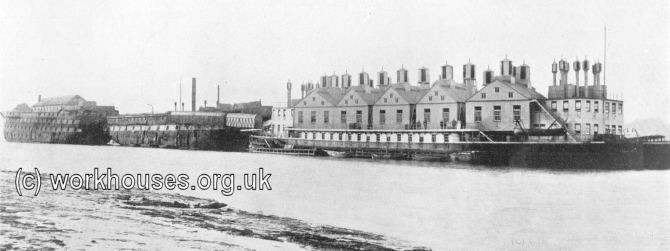

The Atlas, Endymion and Castalia

© Peter Higginbotham

The hospital ships continued in use until 1903 when a permanent smallpox hospital was erected on the land opposite the ships' moorings. The 940-bed Joyce Green Hospital opened on 28th December, 1903, and the old ships were disposed of shortly afterwards. In order to provide temporary additional accommodation during a serious smallpox outbreak in 1901-2, two temporary hospitals, the Long Reach Hospital (300 beds) and the Orchard Hospital were erected adjacent to the Joyce Green Hospital site.

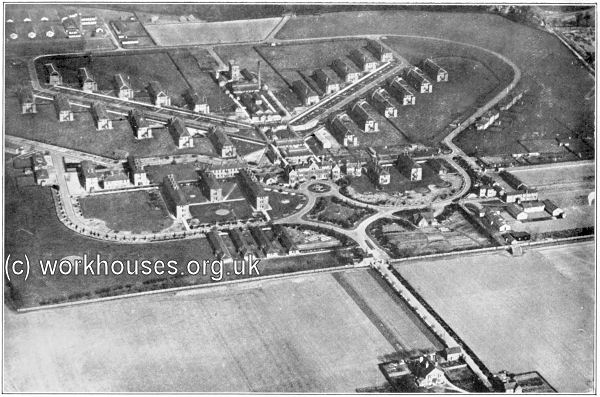

The Joyce Green Hospital, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham

Expanding the Service

In 1891, the Public Health (London) Law Consolidation Bill, revised and confirmed a variety of amendments enactments to public health legislation that had been passed over the previous decade. One of the most significant features of the Act was to authorise the admission of infectious non-pauper patients into MAB hospitals. However, unlike the preceding legislation, no power was given to parochial authorities to recover the maintenance costs from such patients. Instead, these expenses were to be chargeable to the Metropolitan Common Poor Fund. The 1891 Act thus transformed the MAB fever and smallpox hospitals from pauper institutions into England's first free state hospitals for all.

As a result of the 1891 Act, the MAB was faced with the need for a major expansion of its facilities. At its inception in 1877, the Board took over responsibility for around 163,000 infectious or insane paupers. It was now faced with providing care for four and a quarter of a million Londoners of all classes.

Five new fever hospitals were planned, four located south of the Thames, each of which would accommodate 2,000 acute and 800 convalescent cases. Sites, however, were by this time becoming harder to find, and more expensive to purchase. The MAB had already identified a suitable new site in 1890 at Tottenham costing £12,000. However, after lengthy deliberation, the Local Government Board had vetoed its purchase. The MAB the proposed an alternative site at Tooting, which was again turned down. However, in 1892, a violent scarlet fever outbreak hit London and, despite the erection of temporary ward huts, the existing fever hospitals could not keep pace with demand. For the first time in its history, the MAB fever hospitals were obliged to refuse admissions. As a result, the Local Government Board sanctioned the construction of the North-Eastern Hospital on the site at Tottenham. A temporary structure was up and running in seven weeks and on 8th October, 1892, it opened with 500 beds.

In 1893, resurgences of scarlet fever and smallpox, together with threats of cholera and influenza, resulted in setting up of a hospital on the Tooting site. Again beginning as a makeshift structure, the Fountain Hospital opened in October, 1893 providing a further 400 fever beds.

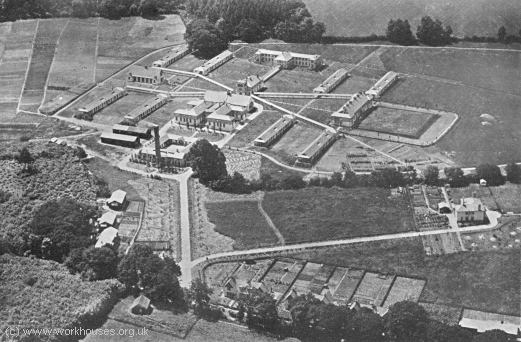

Fountain Hospital, c.1913.

© Peter Higginbotham

Continuing high levels of scarlet fever led to the construction of three further fever hospitals beginning with the Brook Hospital opened at Shooter's Hill on 31st August, 1896; the Park Hospital at Hither Green on 8th November, 1897; and the Grove Hospital on an adjacent site to the Fountain at Tooting on 17th August, 1899. The MAB's ultimate aim was to provide one fever bed for every thousand inhabitants of London.

Park Hospital, c.1913.

© Peter Higginbotham

Brook Hospital, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham

Grove Hospital, c.1910.

For convalescing fever patients, the Northern Hospital at Winchmore Hill was opened in September, 1887. The opening of the Joyce Green, Long Reach and Orchard smallpox hospitals at Dartford in 1902-3 released sufficient accommodation for the Gore Farm to be redeployed as a convalescent hospital.

In the field of venereal and related diseases, the MAB operated two specialist institutions. In 1917, St Margaret's Hospital in Kentish Town was opened to treat Ophthalmia Neonatorum — a form of conjunctivitis mostly commonly contracted during delivery by an infant whose mother is infected with gonorrhoea. In 1919, the Sheffield Street Hospital was purchased from the Westminster Union and opened as a women's venereal disease hospital.

The Mentally Ill

In addition to the large asylums for adult imbeciles at Caterham and Leavesden, and the school for imbecile children at Darenth, the MAB operated a number of other establishments for those with various types of mental problem.

A new 'infirmary for imbeciles' was opened at Tooting Bec in 1903. It was originally intended to bring in around a thousand sick and elderly patients from the Caterham and Leavesden asylums so that they could be in easier reach of the relatives. However, this plan was deferred when the buildings were required to accommodate patients displaced from the County Asylum at Colney Hatch by a disastrous fire in February, 1903. Eventually, it did revert to its original purpose. Tooting Bec also served as a children's receiving home. It later became exclusively used for housing those suffering from senile dementia and eventually had two thousand residents.

In 1911, the Fountain Hospital was converted from a fever hospital to an institution for the accommodation of severely subnormal children.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, a new category of mental deficiency came increasingly to be used — that of the 'feeble-mindedness', a less severe condition than that of 'imbecility' which placed people at Caterham and Leavesden. In 1894, the MAB was given the responsibility of making provision for feeble-minded children from metropolitan poor-law schools. Instead of setting up an institution for such children, the Board adopted the system of 'scattered homes' pioneered by the Sheffield Union in 1893. Houses were acquired in Fulham, Peckham, Pentonville, and Wandsworth, in each of which was placed between twelve and twenty children under the care of foster parents.

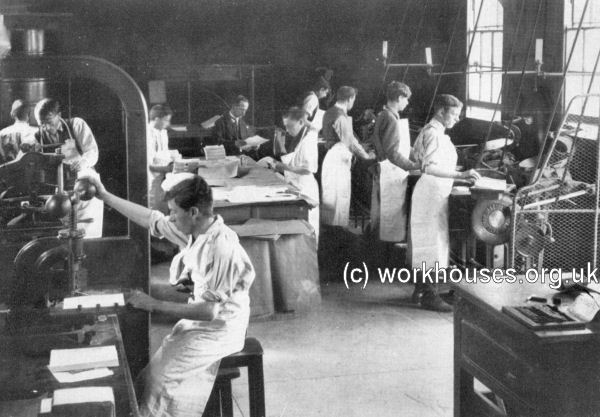

To cater for the feeble-minded beyond the age of 16, several training colonies were set up. The largest was at Darenth, opened in 1904 on a site adjoining the existing school. Here, the less severely handicapped were taught a range of industrial skills and crafts.

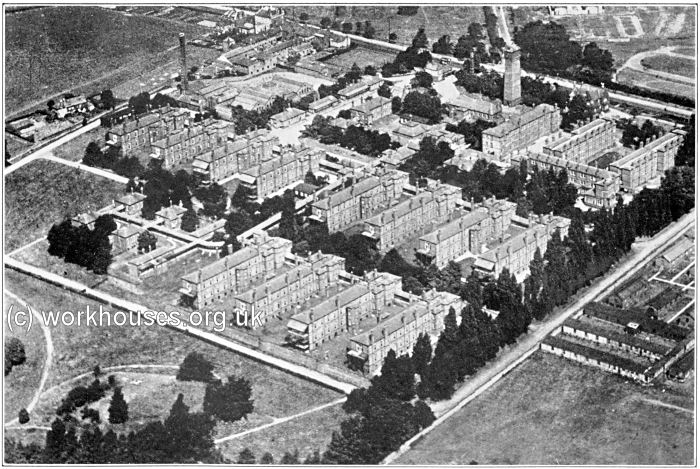

Darenth Training Colony, c.1930.

© Peter Higginbotham

A working colony for male patients, the Bridge Training Home, was opened at Witham in 1906. Older feeble-minded girls were placed at the High Wood School at Brentwood. In 1915, the former Strand Union school at Edmonton was converted for use as a colony for up to 300 male 'sane epileptics'.

Caring for Children

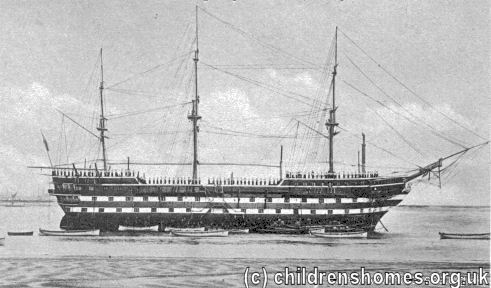

Although children formed a substantial part of the MAB's general intake of infectious sick and mentally handicapped, it also provided for their care in other ways. In 1875, the training-ship Goliath operated by the Forest Gate School District was destroyed by fire. The Local Government Board decided that the ship should be replaced by another vessel, the Exmouth, for the benefit of the whole of London. The MAB took over the management of the scheme which gave naval training to pauper boys aged from thirteen to sixteen, many of whom went on to join the Merchant or Royal Navy.

Training ship Exmouth, 1917

© Peter Higginbotham

In 1897, the MAB was given new responsibilities for: poor law children suffering from diseases of the eye, skin and scalp; educationally subnormal children; those in need of long-term nursing and convalescence; and youth offenders remanded to a workhouse under the 1866 Industrial Schools Act.

To fulfill these new obligations, a new Children's Committee was formed and began by acquiring two existing seaside 'hospital-school' homes. The first, at Herne Bay, was taken over from the South Metropolitan School District which was dissolved in 1902. It reopened as St Anne's Convalescent Home at the end of 1897 with 134 beds. East Cliff House at Margate was purchased from the St Pancras Union. It was extended to accommodate a hundred children and opened in the following June, specialising in tubercular conditions. The buildings were enlarged in 1918-19 and re-opened as the Princess Mary's Hospital for Children. A third establishment, the purpose-built 120-bed Millfield Sanatorium was opened at Rustington in West Sussex in April 1904. It was intended for early cases of pulmonary tuberculosis, or pthisis, and was the only poor law establishment in the country specialising the treatment of this condition.

Millfield Sanatorium, Rustington, 1920s

© Peter Higginbotham

The MAB also acquired two sites on which to erect new hospital-schools for children suffering from ophthalmia. Such inflammatory diseases of the eye, most notably trachoma, were particularly common among poor law children. The White Oak School at Swanley in Kent opened in March, 1903, and theHighwood School at Brentwood in Essex, received its first patients in July, 1904. Each school provided for 360 children distributed among thirty cottage homes. The removal of infectious children from the ordinary schools led to a gradual reduction in the outbreaks of ophthalmia and, in 1919, High Wood School was closed and converted for use as a TB sanatorium.

Another infectious children's condition for which special establishments were set up was that of ringworm — a fungal infection affecting the scalp, the body, the feet, and the nails. Accommodation for around 400 cases was provided in two more establishments acquired from the South Metropolitan School District — Bridge School (the former Witham Union workhouse) which opened in February, 1901, and the Downs School at Sutton, which opened in February, 1903. The introduction of X-ray treatment for ringworm in 1905 led to much speedier treatment of the condition. In 1908, ringworm treatment was concentrated at the Downs School, then transferred in 1914 to the Goldie Leigh Homes in south-east London. The Bridge School was converted to an industrial training home for 'feeble-minded' but 'improvable' boys.

A new hospital erected at Carshalton in Surrey in 1907-9 was originally intended as an additional fever hospital. However, increasing demand for children's facilities led to its redesignation as a general hospital for one thousand children under the name of the Children's Hospital. In 1910, following the accession of King George the Fifth and Queen Mary to the throne, it was renamed Queen Mary's Hospital for Children. Queen Mary's was also home to the first MAB training school for nurses.

Queen Mary's Hospital, Carshalton, 1920s

© Peter Higginbotham

For educationally subnormal children, half a dozen establishments in the style of scattered homes were set up around the capital.

To deal with its obligation in providing remand accommodation for juvenile offenders, the MAB adapted houses it owned in Pentonville Road, Harrow Road, and Camberwell Green. These were opened on 1st January, 1902, and continued in use until April 1st, 1910, when the responsibility for remand homes passed to the London County Council.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) or 'consumption' was a common and, if left untreated, potentially fatal infectious disease in Victorian England. Its nature was not fully understood until the identification of the tubercle bacillus in 1882. Although it was particularly prevalent among the poor, for many years the MAB made no particular provision for its treatment, other than the care of sick children, many of whom were consumptive. A specially convened conference of parochial authorities in 1900 petitioned the MAB to provide sanatoriums for the 'open-air' treatment of the condition. The Local Government Board, who needed to approve such a step, were reluctant to sanction the heavy outlay that would be involved. Change came in 1911 with Lloyd George's National Insurance Act, which included a number of TB-related provisions: 'sanatorium benefit' for workers, the building of tuberculosis institutions, and the funding of research into the disease. Despite some confusion and administrative wrangling between the MAB, the Local Government Board, and the London County Council, the MAB finally took on responsibility for providing TB care facilities for the metropolis.

Initially five hundred beds were provided at the Downs Sanatorium at Sutton, and the Northern Hospital at Winchmore Hill. The St George's Home in Chelsea, a 50-bed facility for advanced TB cases in women, was opened in May, 1914. Further developments were interrupted by the First World War. In 1919, the MAB took over the 80-bed Pinewood Sanatorium at Wokingham which had originally been set up by voluntary effort in 1898. Another acquisition in the same year was the Westminster Union's infirmary at Hendon. This was reopened as the Colindale Hospital in January, 1920, and was later extended to house around 350 patients.

Colindale Hospital, c.1930

© Peter Higginbotham

The Board then purchased the Empire Hotel in Lowestoft which was adapted to accommodate 200 surgical cases. It opened in May, 1922, under the name of St Luke's Hospital. Some of the hospital's balconies were used to create open-air wards.

St Luke's Hospital, Lowestoft, 1920s

© Peter Higginbotham

This was followed a month later by the opening of the 230-bed King George V Sanatorium in Godalming which was erected on a site purchased at the start of the War. This was the MAB's only purpose-built TB institution and, in addition to medical treatment, its mostly male patients were provided with light manual work and industrial training.

King George V Sanatorium, Godalming, 1920s

© Peter Higginbotham

In 1926, a former Greenwich Union workhouse and military hospital at Lee in south-east London was purchased and adapted for around 320 male patients, reopening as the Grove Park Hospital.

The Homeless 'Casual' Poor

In April 1912, the MAB took over the provision of relief for the capital's 'casual paupers' or vagrants which, according to the 1910 census, numbered over 25,000. Prior to this, casuals had been catered for in the workhouse casual wards operated by around thirty separate Boards of Guardians. Typically, a casual would stay one or at most two nights at each workhouse. In return for a night's lodging, three hours labour were required, or nine hours for a two-night stay. Work for men was usually stone breaking or oakum picking. Women also picked oakum or did washing, scrubbing or needlework. However, conditions had varied enormously with vagrants flocking to those wards where detention and work were not enforced, while beds remained unfilled in stricter establishments.

When the MAB took over, its intention was apply a strict and uniform policy of administration. Many of the casual wards it took over were closed or disposed of. By 1921, the number of wards had fallen to six, and by 1929 stood at nine (Chelsea, Hackney, Lambeth, Paddington, Poplar, St Pancras, Southwark, Wandsworth, and Woolwich). Conditions in the remaining wards were gradually improved — the dietary was revised, newspapers were provided, and the old deterrent labour tasks such as stone-breaking were largely done away with.

At the end of 1912, the Board set up a central clearing-house for casuals known as the The Night Office, originally located on a disused steamboat pier near Waterloo Bridge, and from 1921 at Charing Cross railway Bridge. The Night Office had telephone links to the remaining casual wards, and also with the Salvation Army, Church Army, and other voluntary organisations. Casuals requiring accommodation were assessed at the Night Office and given a ticket to provide admission to a specific casual ward or charitable institution. Numbers applying at the Night Office fell from 3,000 a month when it first opened, to around 1,400-1,600 a month following the First World War.

As well as providing overnight accommodation, the Board also attempted to assist helpable casuals to become self-supporting. In 1923, it opened The Hostel on Little Gray's Inn Lane where those genuinely seeking employment could reside in more amenable conditions than the casual wards. From 1924 to 1929, between 1,000 and 2,500 such people were admitted each year.

Ambulance Services

From its rudimentary beginnings in 1881, the MAB established a large network of land and water based ambulance service. Its land ambulances were based at six stations adjoining the Board's hospitals at Deptford, Fulham, Hampstead, Homerton, Stockwell, and Woolwich. Almost the whole of London fell within a three-mile radius from one of the stations.

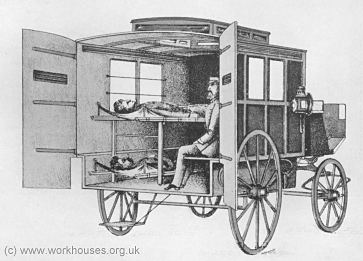

MAB Ambulance Services, 1891.

© Peter Higginbotham

Until 1902, the ambulance fleet was horse-drawn. A steam vehicle, designed to carry eight stretchers, was then introduced to transport patients to the riverside hospitals at a speed of up to 5 miles per hour. The first petrol-driven ambulance appeared in 1904 and could carry a single stretcher at up to 15 mph. The last horse-drawn ambulances were used on 14th September, 1912, a day that marked the end of the once familiar sight of urchins pursuing the slow-moving vehicles shouting 'Fever!'

Interior of First Ambulance, 1880s

© Peter Higginbotham

Ambulance at Park Hospital c.1908

© Peter Higginbotham

The Board operated its own Mechanical Transport Department at Carnwath Road in Fulham which undertook a variety of work including the building of ambulance bodies, and the repair and maintenance of the fleet of vehicles.

Since 1884, the MAB had operated a river ambulance service between London and its hospital ships at Dartford. The five steamers — Albert Victor, Geneva Cross, Maltese Cross, Red Cross, and White Cross — ran from wharves at Blackwall, Rotherhithe, and Fulham. The largest vessel was 143 feet in length and could accommodate 50 reclining patients on its lower and upper decks on the outward journey, and 100 recovered patients on its bridge deck on the way back. One of the smaller steamers was fitted up as a chapel.

Administration

The MAB's headquarters moved several times during its lifetime. After a brief period at No. 6 Westminster Chamber, Victoria Street, at the end of 1867, it moved to 37, Norfolk Street, The Strand, where it stayed until 1881. It then moved to Norfolk House on Norfolk Street, then in 1900 purchased a site at the corner of Carmelite Street on the Victoria Embankment where a purpose-built Head Office was erected. In 1914, expansion of the office space requirements was solved by relocating the Engineer-in-Chief's office to premises at Sheffield Street.

MAB Carmelite Street Offices

© Peter Higginbotham

The First World War

At the start of hostilities in 1914, the MAB briefly undertook the provision and management of accommodation for destitute alien enemies. On 27th August, it took over the Holborn Union's Endell Street workhouse and a total of 363 persons, mostly Germans an Austrians, were admitted. Within a few weeks, this role was taken over by the military authorities.

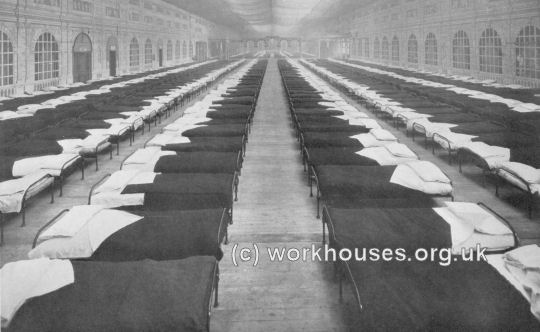

The Board's main wartime work was the operation of institutions for housing war refugees from the Continent, chiefly from Belgium. In all, around 13,000 beds were provided and about 160,000 refugees were dealt with. The first location to be adopted for this purpose was Westminster Union's disused Poland Street workhouse which, on September 5th, admitted 200 Russian Jews, mostly from Antwerp. A week later, the premises were handed over to the Jewish authorities and continued in operation as the Poland Street Institute for Jews. Refugee accommodation was provided at two other establishments taken over from the Westminster Union — the former the Strand Union workhouse and Millfield School, both at Edmonton. The former St Giles Union premises on Endell Street contributed 1,000 beds. Some of the MAB's own establishments were adopted, including the Park Hospital and the Hackney Wick and St Marylebone casual wards. By far the biggest contribution came from two vast refugee camps set up in 1914 at Alexandra Palace and the Earl's Court Exhibition Centre, each of which provided 4,000 beds.

1000 beds in The Queen's Palace, Earl's Court, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham

In June, 1918, about 1,140 refugees from Russia arrived in England. As they had been in contact with smallpox, they were housed in isolation at the Joyce Green Hospital.

As well as dealing with refugees, the Board contributed two of its establishments, the Brook Hospital at Shooter's Hill, and the Grove Hospital at Tooting, as military hospitals for the treatment of war casualties. In addition, the Southern Hospital at Dartford and the North-Eastern Hospital at Tottenham were placed at the disposal of the US military authorities. The temporary buildings of the Orchard Hospital at Dartford, erected in 1902, were lent to the War Office from 1915 to 1919 for the use of overseas troops, mainly Australians.

Orchard Hospital, c.1916.

© Peter Higginbotham

Brook Military Hospital, c.1916.

© Peter Higginbotham

The End of the MAB

In 1928, the government announced proposals for the reorganisation of local government in England and Wales, including the abolition of Poor Law Guardians and the transfer of their responsibilities to the County Councils and County Borough councils. The MAB had its final meeting at its head Offices on the Embankment on 29th March, 1930. On the 1st April, 1930, the Board's duties and responsibilities passed to the London County Council (LCC), which also took over all the hospitals operated by the capital's Boards of Guardians. The LCC inherited a total of thirty-seven poor law establishments:

- 13 institutions

- 1 home for the aged

- 8 homes for children

- 1 home for children and aged women

- 3 residential colonies for the able-bodied (Dunton Farm, Sutton, and Hollesley Bay)

- 9 MAB casual wards, plus the Hostel and Night Office

The MAB's material legacy included a rich portfolio of infectious diseases hospitals, TB hospitals and sanatoriums, children's hospitals, and number specialist establishments, not to mention the ambulance services, laboratories, training and research establishments, and all the supporting administrative structures required to run them. Less tangibly, over a period of sixty years, the Board had transformed the health services of the capital and laid the foundations for the nationwide system of medical care that was to emerge in 1948.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Ayers, Gwendoline, M. (1971) England's First State Hospitals and the Metropolitan Asylums Board (Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, London).

- Powell, Sir Allan (1930) The Metropolitan Asylums Board and its Work, 1867-1930. (MAB, London)

Records

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Has virtually all the surviving records for the Metropolitan Asylums Board and its instititutions. Search their catalogue at https://search.lma.gov.uk/.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.