The Workhouse in Ireland

Although workhouses had existed in Ireland before the system created by the Irish Poor Law Act of 1838, their use was on a much smaller scale than was the case in England and Wales.

The Eighteenth Century

In 1703 an Act of the Irish Parliament provided for the setting up of a House of Industry in Dublin 'for the employment and maintaining the poor thereof' (O'Connor, 1995). A workhouse was subsequently erected on land at the south-west of James's Street and was administered by 'The Governor and Guardians of the Poor' whose members included the Lord Lieutenant, the Lord Mayor, the Lord Chancellor, the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, sheriffs, Justices of the Peace, and members of the Corporation. This body, which met monthly, had powers to place people in the workhouse, and to discipline those already there if they disobeyed workhouse regulations. Punishments could include flogging, imprisonment or deportation.

The main classes of inmate were 'sturdy beggars', 'disorderly women', the old and infirm, and orphan children. Up to 100 men and 60 women slept in bunk-like beds crammed into the workhouse cellars which were 240 feet (75 metres) long by 17 feet (5 metres) wide. The diet was made up of bread, milk, porridge, gruel, and 'burgoo' which was oatmeal in cold water seasoned with salt and pepper.

The Governors also provided care for abandoned children aged between 5 and 16, and could apprentice them out. A further Act in 1730 extended this role to cover all foundling children and a substantial part of the workhouse was allocated to this, with the workhouse becoming the Foundling Hospital and Workhouse of the City of Dublin. At one of its gates, a basket was fixed to a revolving door. Someone wishing to leave a child anonymously could place it there, ring the porter's bell, and then depart.

In 1735, the Irish Parliament passed a similar Act for 'erecting a workhouse in the City of Cork for employing and maintaining the poor, punishing vagabonds and providing for and educating foundling children.' This scheme was funded by a tax of a shilling per ton on all coal and anthracite imported into Cork. A Board of Governors was set up in 1736 to administer the scheme and the following year found a suitable site on Watercourse Road. Eventually opening in 1747, the new institution seems to have ended up entirely as a foundling hospital rather than the combined workhouse and foundling hospital originally envisaged.

Belfast benefited from the work of the Belfast Charitable Society, formed in 1752. It eventually raised enough funds for the erection of a workhouse which opened its doors in 1774. A House of Industry 'for the suppression of mendicity and the promotion of industry among the poor' was established in Smithfield in 1809 and supported by voluntary contributions. The unemployed poor were set to work at occupations such as weaving, spinning, knitting, and net-making and their earnings were supplemented by donations of food and clothing.

In 1768, the Royal Dublin Society published proposals for creating a county poor-house in each of the country's county towns. These proposals had little direct result, although may have influenced a 1772 Act of the Irish Parliament for the setting up of 'corporations' throughout the country. These were empowered to set up voluntarily-funded establishments 'for the reception of the helpless poor and for keeping in restraint sturdy beggars and vagabonds' and 'to build hospitals, to be called workhouses or houses of industry, for the relief of the poor, as plain, as durable, and at as moderate expense as may be.' They could also license beggars by means of a 'badge' without which offenders would be placed in the stocks.

As a result of the 1772 Act, a new House of Industry was set up at the north side of Dublin. It consisted of an asylum for the aged and infirm poor and incurable lunatics, together with several hospitals and a dispensary.

Limerick erected a House of Industry in 1774. Its construction was funded by Grand Jury presentments (local taxes) on the county and city and was initially intended to accommodate 200 inmates although this later increased to 380. In 1817, it was reported that 'the Limerick House of Industry comprehends four distinct establishments: it is not only an asylum for paupers and vagrants, but a nursery-school for deserted children, a Lock Hospital, and a retreat for Lunatics.' By 1830, its now eight divisions were categorised as '1. An asylum for lunatics and idiots; 2. A nursery for deserted infants; 3. A workhouse for the healthy poor; 4,5. Two schools for the education od children of both sexes; 6. A house of correction for vagrants and prostitutes; 7. A retreat for incurables from the hospitals and convalescents from fever. 8. A house of refuge for the infirm and sick poor.'

Ennis had a House of Industry from around 1775. It was funded by private subscriptions and governed by a corporation under the 1772 Act. It was located at the north side of the town, adjoining the County Infirmary, and contained three male and four female wards.

Waterford's House of Industry, to which was attached a lunatic asylum, was erected in 1779, at a cost of £1500. Its board of governors rejoiced in the title of 'the President and Assistants instituted for the relief of the poor, and for punishing vagabonds and sturdy beggars for the county and county of the city of Waterford.' An average of 200 to 300 paupers were received each year and were occupied in domestic chores and in various trades.

A House of Industry was set up in 1811 at Clonmel to act as 'a common receptacle for all descriptions of malfortunes, serving at the same time as a place of confinement for vagrants and lunatics as well as an asylum for the poor and helpless.' (Lonergan, 2000) Pigot's 1824 Directory of Ireland contained the following description of the establishment:

Houses of Industry also existed at various times at Kilkenny, Newtownards, and Wexford.

The Post-Union Years 1830-1838

After 1800, when Ireland became part of Great Britain under the Act of Union, the British government made numerous but ineffectual attempts to address the desperate and widespread poverty in Ireland. A succession of Parliamentary Select Committees in 1804, 1819, 1823 and 1830, produced virtually no practical results, neither did the 114 Royal Commissions and 61 Special Committees of Enquiry which investigated conditions in Ireland between 1800 and 1840.

The 1830 Select Committee, for example, recommended a variety of remedies including: emigration, the improvement of bogs and wastelands, the draining of marshlands, the introduction of large-scale public works projects, better education, the encouragement of manufacturing industry, the expansion of fisheries, and the introduction of a system of poor laws. The extended provision of workhouses was not regarded as a useful option. Little government action resulted from this report, although an Irish Board of Works was established in 1831 to set up public works schemes such as road-building.

What eventually did stir the Government to further activity was increasing concern over the growing influx of Irish immigrants to Britain. On 25th September 1833, yet another Royal Commission was appointed to investigate 'the conditions of the poorer classes in Ireland, and into the various institutions at present established by law for their relief; and also whether any and what further remedial measures appear to be requisite to ameliorate the condition of the Irish poor or any portion of them.'

The 1833 Royal Commission comprised ten members with Dr R Whatley, the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, as it chairman. While it was deliberating, the landmark 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act was passed, which introduced a new scheme for England and Wales whereby the only form of poor relief was to be via the workhouse. The 1833 Commission, reporting in 1836, felt that such a scheme would be not be suitable for Ireland where the problem was more one of lack of available work, rather than of able-bodied men's reluctance to undertake it. Their report instead proposed the setting up of a Board of Improvement and Development which would undertake such measures as:

- Reclaiming waste land and draining bog-land

- Increased funding for the Board of Works which would undertake useful public works

- Direct employment of labour for roadworks by local authorities

- The development of trade, manufacture, fisheries and mining

- Improvements to housing

- Increasing leasing and tenure of land to encourage its improvement

- Provision of agricultural instruction

- Sunday-closing of public houses and preventing the sale of groceries and liquor on the same premises

The Report received a mixed reception. The Secretary of State for the Home Department, Lord John Russell, felt that the Committee had considered some rather too general matters which were outside their brief. In September 1836, one of the English Poor Law Commissioners, George Nicholls, was sent to Ireland 'in order to arrive at a practical conclusion with respect of any measures to be introduced into Parliament in 1837 for the benefit of the poor in Ireland.' In particular, Nicholls was to assess whether a system of poor relief funded by a local poor-rate would be effective, and whether a workhouse system could be established. Essentially, he was asked to see to what degree the newly established English system could be made to work in Ireland.

In his whistle-stop six-week tour of the country, his first-ever visit to Ireland, Nicholls visited places in all four provinces including Dublin, Carlow, Thurles, Cashel, Tipperary, Clonmel, Cork, Kilkenny, Galway, Connemara, Westport, Castlebar, Ballina, Sligo, Enniskillen, Armagh and Newry. Irish patriot Daniel O'Connell ridiculed the speed of this exercise and claimed that Nicholls 'was whirled in a post-chaise at public expense, from Dublin to Cork, from Cork to Sligo, from Sligo to Belfast... He calculated everything and was accurate in nothing.'

Failing (or refusing) to acknowledge that the fundamental problems of poverty in Ireland were entirely different in the extent and nature to those in England, and required a different remedy (a fundamental investment in, and development of, the country's resources), Nicholls recommended that the Ireland adopt the English workhouse system. He suggested that new workhouses in Ireland should acquire a plot of land of between six and twelve acres, whose cultivation could provide labour (and food) for its inmates. He also envisaged that workhouses might perform a useful role in local government activities.

Early in 1837, the Government announced its proposals for a Bill based on Nicholls' recommendations. It was closely modeled on the 1834 Act for England and Wales, with poor relief being locally financed through a poor rate, and being offered only through the workhouse. The proposed scheme for Ireland differed in one or two respects. For example, one third of each Board of Guardians was to comprise non-elected ex officio members such as local magistrates. Ministers of religion were (unlike in England) to be ineligible for the office of Guardian. Out-relief was to play no part in the scheme.

Criticism for the proposals was immediately forthcoming, both from landlords who were alarmed at the possible expense of poor rate, and from their tenants to whom the prospect confinement in the workhouse was an anathema. The Bill, drafted by Nicholls, was introduced on 13th February 1837 where it met considerable opposition, particularly from Irish MPs and also from Irish peers when it was considered by the House of Lords.

The Bill's progress was delayed by the death of William IV in June, during which interval Nicholls returned to Ireland to visit some of the northern counties omitted on his previous visit. He found no reason to revise his proposals. The Bill was reintroduced on 1st December, and despite vigorous opposition from Irish MPs (uniquely united on this matter) the Bill was passed by a majority of 234 votes to 59. The new Act 'for the more effectual Relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland' passed into law on 31st July 1838.

The 1838 Act

The main provisions of the 1838 Act were:- The extension of the existing Poor Law Commissioners' powers to Ireland, with the appointment of Assistant Commissioners who were to implement the Act in Ireland.

- The division of the country into Poor Law Unions based on Irish electoral divisions which were themselves made up from townlands.

- The creation of a Board of Guardians for each Union, two-thirds of whom were to be elected, the other third to be appointed ex officio.

- The setting up of a workhouse in each Union.

- The collection of a local poor-rate to finance the system.

- Assistance for emigration.

Initially, 130 Unions were created, based upon 2,049 electoral divisions. The divisions were composed of townlands, a peculiarly Irish unit, traditionally of 120 Irish acres in area. (Between 1848 and 1850, an additional 33 Unions were created by subdividing and reorganizing the boundaries of some existing Unions, particularly in the west of the country. Detailed lists and maps of the Irish Unions are included on other pages.)

Boards of Guardians were elected annually on 25th March. Only rate-payers were eligible for election, which effectively disenfranchised most of the native Irish who were usually tenants at this time. Rate-payers were allowed between one and six votes depending on the size of a valuation of their property.

Differences Between the English and Irish Systems

There were some significant differences between Ireland's new poor relief system and the existing one now operating in England and Wales:

- In Ireland, out-relief was not to be allowed in any form whatsoever

- The Poor Law Commissioners had much greater control over the operation of Irish unions:

- Ownership of workhouse lands and buildings was vested in the PLC.

- They could dissolve a Board of Guards and substitute their own paid officials.

- They scrutinised the weekly Board minutes from each union to ensure they did not deviate from official policy and regulations.

- They were responsible for matters such as the appointment of chaplains.

- There was no law of settlement in Ireland. Engalnd could remove destitute Irish back to Ireland, but not vice versa.

- Clergymen were barred from membership of Boards of Guardians.

The New Workhouses

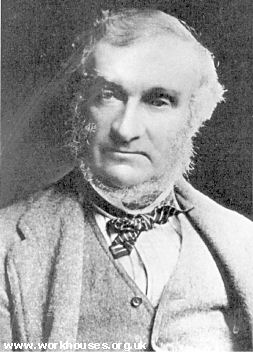

The new workhouse building project began in January 1839, with the arrival in Dublin of architect George Wilkinson, who had designed a number workhouses in England and Wales. Wilkinson was employed, at a salary of £500 per annum, to undertake the design work for all 130 new workhouses. His brief from the Poor Law Commissioners stated that: 'The style of building is intended to be of the cheapest description compatible with durability; and effect is aimed at by harmony of proportion and simplicity of arrangement, all mere decoration being studiously excluded.' As well as design work, Wilkinson had to inspect and report on all the prospective workhouse sites being proposed by each local Board of Guardians.

George Wilkinson, the architect of the Irish workhouse.

Within two months, Wilkinson had devised model plans upon which almost all Irish workhouse buildings would be based. Below are illustrations of his plans for workhouses for 800 inmates (in each case, an enlarged view can be obtained by clicking on the image).

Workhouse design for 800 inmates - Bird's-eye view.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Workhouse design for 800 inmates - ground-floor plan.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A good example of a Wilkinson's designs can be seen at Parsonstown as shown in the aerial view below.

Parsonstown aerial view from the east

Courtesy of Margaret Hogan.

The workhouse was divided into male and female sides, with the male inmates usually placed at the right. At the front of the site was a small entrance block whose ground floor contained a porter's lodge, waiting hall, and receiving rooms. Upstairs were the Guardians' Board Room, with small dormitories to each side, and a store for inmates' own clothes in the attic above. The receiving rooms were used to hold new inmates prior to their transfer to the main workhouse. They were also sometimes employed — to official disapproval — for housing tramps or 'night-lodgers' overnight. The example below is from the Swineford workhouse:

Swineford entrance block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Set back from the entrance block was a much larger accommodation block, with quarters for the workhouse Master and Matron at the centre. At each side on the ground floor were separate school-rooms for boys and girls, with the children's dormitories above. At the ends of this block was accommodation for adult men and women. Unlike in England and Wales, the infirm and the able-bodied were not segregated although rooms the aged and infirm were generally placed on the ground floor. An example of this type of block is shown from the Mullingar workhouse:

Mullingar accommodation block, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The space in front of the main block was divided into enclosed yards for boys and girls, with a garden at the centre.

Loughrea workhouse garden, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.

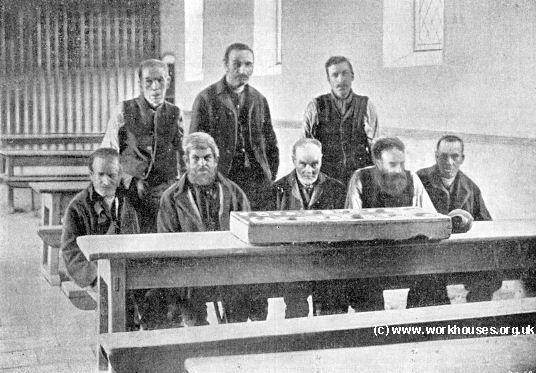

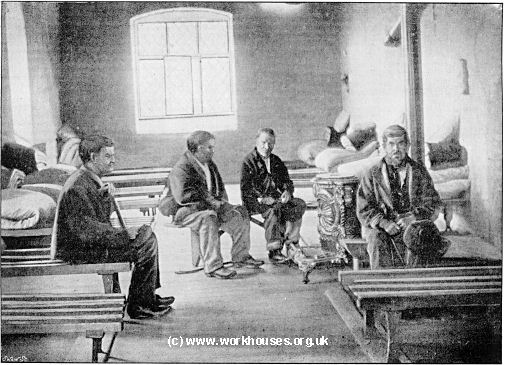

Bailieborough workhouse inmates, c.1895.

To the rear of the accommodation block were the kitchen and washhouse (laundry) and a central spine containing the dining-room which also served as a chapel.

Cellbridge main block, kitchen, chapel/dining-hall 2003.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the rear stood the infirmary and wards for "idiots".

Lisburn rear of main block, chapel/dining-hall and infirmary block, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

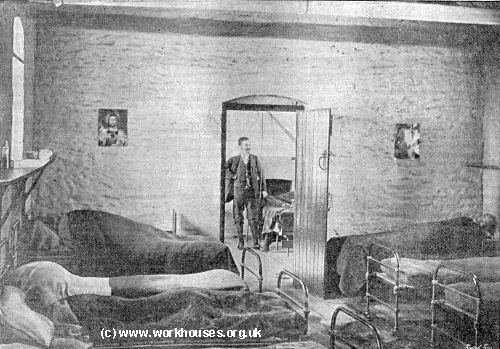

Cootehill workhouse infirmary, c.1895.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cootehill workhouse infirmary, c.1895.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cootehill workhouse - lunatic inmates, c.1895.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Workhouse construction proceeded apace, and by April 1843, Wilkinson was able to report that 112 of the new workhouses were finished, and 18 others were almost complete. In a few cases, such as Dublin, Clonmel and Fermoy, existing buildings were being adapted for the new system.

However, even when the buildings were ready, they did not always come into operation immediately if the Guardians had be unable or unwilling to collect sufficient poor rates to enable this. In Westport, for example, workhouse was declared fit for the admission of paupers on 15th November 1842 but stayed closed due to a lack of operating funds. For two years, the Guardians attempted to collect the poor rate, sometimes with the help of police and troops. Eventually, in 1844, a warship and two cruisers sailed into Clew Bay to assist — without success. The Board of Guardians resigned and a new Board was elected. The workhouse was opened only after they were served a court order and the first inmates were finally admitted on 5th November 1845. As a last resort, the Poor Law Commissioners could forcibly dissolve a Board of Guardians and install their own vice-guardians in order to get the workhouses open - a fate which befell the Castlerea and Tuam Boards in 1846. Difficulties in collecting the poor rate, together with people's general reluctance to sacrifice their independence, meant that even by the summer of 1846, the workhouses that were open were still only half-full.

For those that did enter the workhouse, conditions were often miserable. The separate web page on workhouse life describes the regime in English workhouses. In Ireland, things were even more severe. Dormitories were cramped and lacking ventilation. Beds consisted of a platform of planks and a straw mattress covered rough rags. There was often a lack of water and at night, the only toilet facilities were large urination tubs in each ward which often overflowed.

In 1844, the Poor Law Commissioners issued an official rule-book for the running of workhouses. The rules were adapted from those in use in England and Wales. You can read the full text of the 1844 rules.

Diet

The formulation of an appropriate diet for Ireland's workhouse inmates was a matter with which the Poor Law Commissioners grappled for several years. The principle of "less eligibility", by which workhouse conditions were never to be better than those enjoyed by an independent labourer outside, was particularly difficult to apply to a population whose ordinary diet was often barely above subsistence level. As a starting point, two sources of information were examined. The first, a review of the diets provided at other institutions such as Houses of Industry and prisons, showed that inmates were typically given a breakfast of oatmeal and milk, and a middle of the day dinner of potatoes and milk, but no supper. The second, a survey of poor labourers' diets in various parts of the country, showed a frequent pattern of potatoes and milk for both breakfast and dinner, again within supper often being omitted. Herrings were sometimes substituted when milk was in short supply. The initial proposals for the workhouse dietary comprised a breakfast of stirabout (oatmeal porridge) and milk, with a dinner of potatoes and milk. However, pressure from the two Dublin unions to include meat soup dinners on two days a week resulted in unions being given the option of three different menu plans. Dietary 1 (below) contained a revised two-meals-a-day menu containing no meat.

| BREAKFAST | DINNER | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oatmeal in Stirabout | Buttermilk | Potatoes, weighed raw | Buttermilk |

| 7 oz. | 1 Pint, or New-milk, ½ Pint | 3½ lbs. | 1 Pint, or New-milk, ½ Pint |

Dietary 2 was the same as Dietary 1 but with a twice-weekly meat soup dinner. Dietary 3 (below) was a three-meals-a-day regime, but with no meat included.

| BREAKFAST | DINNER | SUPPER | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oatmeal in Stirabout | Buttermilk | Potatoes, weighed raw | Buttermilk | Oatmeal in Stirabout | Buttermilk |

| 5 oz. | 1/3 Quart | 3 lbs. | 1/3 Quart | 4 oz. | 1/3 Quart |

| or Bread 6 oz. | |||||

The Famine

For many of Ireland's eight million inhabitants, the potato was the staple component of the diet. In the summer of 1845, reports of blight began to appear, first on the continent and then in southern England. By August it had reached Ireland, and a substantial part of that year's crop rapidly became black and inedible.

Initially, the full significance of the blight was underestimated. A similar problem had occurred in 1832, and it was generally assumed that only that year's crop was likely to be affected. Through the end of 1845 and into 1846, the most obvious effect was on the price and availability not only of the remaining potato stocks, but also of other foods such as wheat and oatmeal.

Official action to relieve the growing food shortages was primarily through the Relief Commission for Ireland, set up by the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, in November 1845. The main aims of the Commission were the formation of local fund-raising committees, and the encouraging of landlords to create employment schemes, up to half of whose costs would be borne by the Government. The Board of Works was authorized to instigate new road-building projects from which extra employment would result. The Commission also set up food depots around the country for the storage of "Indian meal" (maize corn imported from America) which local relief committees would be able to resell at cost price should food prices continue to rise. This subsequently happened, and Indian meal was to become a major part of many people's diet for several years.

Unhappily, the summer of 1846 saw the return of the blight and an escalation in the desperation and misery. On 28th September 1846, the scarcity and price of food, and the shortage of work, resulted in the Dungarvan riots where grain stores on Dungarvan Quay were looted.

Inside the workhouses, conditions were steadily getting worse. Stables and washrooms were being pressed into service as overflow accommodation, and auxiliary workhouse accommodation was being rented to cope with the rising numbers. However, the finances of many Unions, which had already been parlous, were now exhausted and they closed their doors to further admissions. The costs of providing extra accommodation, as well as the increased costs of feeding the inmates, were already pushing some Unions into insolvency. On top of this, diseases such as typhus fever and dysentery were widespread. The Quaker relief-worker James Tuke described at Swineford workhouse in November 1846:

The Relief Commission's attempts to generate employment through increased public works schemes proved hopelessly inadequate. There was insufficient work to satisfy demand, the wages were insufficient to keep up with escalating food prices, and food was often impossible to obtain because of the poor distribution network. The bitter irony is that many Irish farms did in fact continue to produce high-quality foods such as grain and meat throughout the famine years but landlords exported them to Britain because the local peasantry lacked the money to buy them. The British government connived in this activity by providing troops to protect some of these shipments.

Unsurprisingly, in these desperate conditions, civil unrest grew. The workhouse at Ennis was overwhelmed by the numbers wanting to enter and needed police protection for its doors. On Christmas Eve, 1846, Captain Wynne, the District Inspector for Clare, wrote:

At the start of 1847, following similar voluntary schemes set up by groups such as the Quakers, some minimal relief for those outside the workhouse came in the form of Government soup kitchens set up under the Temporary Relief Destitute Persons Ireland Act.

Soup-kitchen vessels at Carrick-on-Shannon.

© Peter Higginbotham.

However, the 'Soup Kitchen' Act lasted for only six months, after which the Poor Law Extension Act of 1847 introduced a system of discretionary out-relief, which again had to be funded by the local poor rate. A highly controversial aspect of this new scheme was that anyone occupying more than a quarter of an acre of land was ineligible unless they gave up their tenancy. Understandably reluctant to give up their only potential livelihood, many 'quarter-acre' men were to perish before the rules were relaxed the following year.

During 1847, often known as "Black '47", workhouses struggled to provide extra accommodation much of which was aimed at coping with the ravages of typhus fever and dysentery. A number of fever hospitals were rapidly erected, although in some cases these consisted of little more than wooden sheds. Financial crises continued — Ballina workhouse had debts of £2,000 and Castlebar of £3,000. The debts of Ennis Union were to reach £20,000 by 1849. Throughout all this, the Government Exchequer continued to demand repayments on the loans taken out by most Unions to finance the building of the workhouse.

The Poor Law Commissioners made considerable use of their powers to dissolve Boards of Guardians that were "failing to provide sufficient funds, or to apply them efficiently in relieving the destitute" and to install their own officers. A total of 32 boards were dissolved in 1847 with 6 more in 1849. These were mostly located in the west of Ireland as shown on the map below.

Boards of Guardians dissolved 1847-9.

© Peter Higginbotham.

As it turned out, the direct effects of potato blight diminished relatively quickly — even as early as the 1847 season, what potatoes were planted seemed to have cropped reasonably well. What contributed the continuing food shortages was the difficulty in obtaining seed potatoes for planting, and also an understandable general reluctance at that time to risk wasting money in planting such seed. In April of 1848, Captain Edmund Wynne wrote from Carrick-on-Shannon Union to the Poor Law Commissioners expressing gloom about the harvest prospects for that year:

Sir,

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 22nd instant, relative to the agricultural prospects in my district.

In many electoral divisions I regret to say the prospect is anything but cheering, while in some there is nearly an average breadth of corn (for this country), and very great anxiety to plant the largest amount of potatoes their means of purchasing seed will admit of.

The breadth already planted in the district, with the exception of the Electoral Divisions of Carrick, Elphin, part of Killucan, and part of Drumsna, is not considerable. The great obstacle will be found the procuring of seed, as this district produced scarcely any potatoes last year; and the small portions that now remain are of the worst description, scarcely to be depended on for seed, from their not having ripened sufficiently. Our market is supplied from the coast and parts of Mayo, where the potatoes did comparatively well last year. The market price here is 40 per cent. higher than in Swineford or Ballaghaderreen. I have no doubt but. that if a facility of procuring seed were afforded, an average crop of potatoes might be reckoned on in the greater portion of my district.

There is at present available two years' manure, not however twice the quantity of ordinary years, as last year manure was not collected with as much industry as if the prospect of the potato crop had been different, but there is a large quantity available at this moment.

I do not think it will be found possible in this Union to organize a committee to enable us to take advantage of the opportunity of procuring seed which the Central Committee holds out. I have however done all in my power to promote its formation.

In the mountain districts some oats will yet be sown, and some barley in any land which may be suited to that grain; but I do not expect that the amount will be any thing considerable.

I do not think that any turnips will be sown if potatoes can be procured for seed.

The corn crops wherever over ground appear healthy though backward, but from the temper of the soil and climate such is always the case.

I have, &c.,

EDMUND WYNNE.

At the beginning 1849, when it was starting to seemed that the worst was over, a final misery descended on the weakened population in the form of an epidemic of Asiatic cholera. It was not until October that the epidemic abated. In the same year, some small financial relief to the 22 worst affected unions in the west of Ireland came via the "Rate in Aid" Act. The unions received funds from government which were then repaid by a 6d rate levied by all the other unions. Many of the unions assisted by the scheme were those which had been temporarily dissolved by the Commissioners, as shown on the map below.

Unions assisted via Rate in Aid, 1849.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the end of the famine years, it was estimated that at least a million people had died, either directly from starvation, or from the diseases it brought in its wake such as typhus fever and dysentery. A further contributory factor was the nutritionally poor Indian meal which became a major part of the diet of many poor, particularly in the workhouses.

New Legislation

In 1847, in the midst of the famine, two significant pieces of legislation had come into effect relating to poor relief in Ireland. The first, in June, was An Act to Make Further Provision for the Relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland. This officially sanctioned - for the first time - the option of giving out-relief to the old, the infirm, the sick, and to poor widows with dependent children. If a union's workhouse was full, or harbouring an infectious disease, out-relief could also be offered to other classes of destitute persons for up to two months. In the case of able-bodied claimants, however, out-relief was to be provided only in the form of food. The Act also gave the Poor Law Commissioners further powers to dissolve or alter unions, to dissolve a board of guardians, to purchase additional land for use as a cemetery or the erection of fever wards, and to provide a chapel.

The following month, An Act to Provide for the Execution of the Laws of the relief of the Poor in Ireland, instituted the Irish Poor Law Commissioners as a independent body, and no longer under the control of the Commissioners for England and Wales. Although the new Irish PLC initially took on all the rules, orders and regulations of the existing administration, the Act said nothing about the form that poor relief should take, i.e. there was no prohibition on out-relief.

Emigration

Emigration had been encouraged by a succession of British governments as a way of reducing the number of destitute persons and the demands they could place on the poor rate. Since the 1838 Irish Poor Law Act, Unions had been empowered to spend up to one shilling in the pound (i.e. five per cent) of the poor rate to 'assist poor persons who would otherwise have to be accommodated in the workhouse' in emigrating. This was primarily to the British colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. From 1840, the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission (an offshoot of the British Colonial Office) supervised emigration from Britain and Ireland to the colonies. The scheme was extended in 1848 to include other non-colonial countries such as America. In the ten years from 1845, a total of two million emigrated from Ireland.

Emigration was often encouraged by landlords who saw it as a way of clearing their land of unwanted tenants, and also reducing the poor rates to which they contributed. In some cases, estate owners chartered their own ships for the transport of emigrants.

With a surge in the demand for passages, conditions on vessels declined, becoming increasingly overcrowded and insanitary. Deaths in passage were as high as twenty per cent, and some unseaworthy vessels sank before completing their journeys. Because of this, emigrant vessels came to be known as 'coffin ships'. The Irish National Famine Monument at Croagh Patrick in Co. Mayo is based upon the grim emblem of a skeleton-strewn coffin ship.

Irish National Famine Monument, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

New Unions and Workhouses

In 1848, a Boundaries Commission reviewed the existing size and composition of each of Ireland's poor law unions. It proposed the creation of up to fifty new unions, of which thirty-two eventually took place between 1849 and 1850 (one other new union, Dingle, had already been established early in 1848). The new unions, predominantly in the west of Ireland, were created by subdividing some of the existing unions, together with some additional boundary adjustments where necessary. For example, in County Clare, the northern part of the Ennistymon Union was split off to create the Ballyvaughan and Corofin Unions. The thirty-three new unions were Ballymahon, Ballyvaughan, Bawnboy, Belmullet, Borrisokane, Castlecomer, Castletownbere, Castletowndelvin, Claremorris, Clonakilty, Corofin, Croom, Dingle, Donaghmore, Dromore West, Glenamaddy, Glin, Kildysart , Killala, Kilmacthomas, Millstreet, Mitchelstown, Mountbellew, Newport, Oughterard, Portumna, Schull, Strokestown, Thomastown, Tubbercurry, Tulla, Urlingford and Youghal. The new unions' administrative centres are shown in red on the map below.

Centres of the new Irish unions.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Eighteen of the new unions proposed by the Boundaries Commission were not created. Their names were: Killybegs (to have been formed from parts of the Donegal and Glenties unions), Riverstown (Boyle, Sligo, Tobercurry), Cossann (Galway, Tuam, Loughrea), Killorglin (Killarney, Chairciveen, Tralee), Castleisland (Tralee, Killarney), Milford (Croom, Kanturk, Kilmallock, Newcastle), North Cork (Cork), Cappamore (Limerick, Tipperary, Kilmallock), Drumkeeran (Manorhamiltion, Enniskillen, Carrick-on-Shannon), Arvagh (Cavan, Granard, Longford, Mohill), Ballymore (Athlone, Ballymahon, Mullingar), Ferbane (Parsonstown), Mountrath (Abbeyleix, Mountrath, Roscrea), Killedmond (Carlow, New Ross, Enniscorthy), Blessington (Naas, Baltinglass), Kildare (Athy, Edenderry, Naas), Newtown Mount Kennedy (Rathdrum), and Kilrea.

Medical Developments

During the 1850s and 1860s, the Irish poor relief system was involved in several significant developments in the provision of medical care.

Dispensaries. In 1851, the Medical Charities (Dispensary) Act placed Ireland's charitable dispensary system under the control of the IPLC. Within each union, dispensary districts were formed, with a total of 723 being created across the country — an average of between four and five per union. The number of dispensaries operating was 960 in 1853, rising to 1,071 by 1872. Each district had its own dispensary where the poor could obtain free medicines and medical treatment from the dispensary medical officer, with the costs being borne by the Boards of Guardians and funded through the poor rate. Dispensaries were usually erected at or near workhouses, such as the one shown below at Navan.

Navan workhouse dispensary, 2002.

© Peter Higginbotham.Vaccination. The 1840 Vaccination Acts had introduced voluntary vaccination in Ireland under the management of the Poor Law Commissioners. Its take-up had been limited, due in part to the fees paid to the doctors contracted to do the work — a shilling each for first 200, then sixpence each thereafter, compared to a flat rate of 1s.6d each received by doctors in England and Wales. In 1851, vaccination became a standard part of the duties of dispensary medical officers, with no extra fee being paid. In 1858, efforts were made to increase the rate of vaccination by creating vaccination districts and paying a flat-rate fee for each successful vaccination. Compulsory vaccination was introduced in Ireland in 1863, ten years later than in England and Wales.

Medical Care for all Poor Persons. From 1856, workhouse fever hospitals had been allowed to admit any "poor person" - i.e. those who were poor but not sufficiently destitute to require entry into the workhouse. In 1862, the Poor relief (Ireland) Act extended this provision to all other conditions — something that had been happening illegally for some years before.

Sisters of Mercy. The Sisters of Mercy, a Roman Catholic religious order particularly associated with caring for the needs of the poor and sick, were first allowed to act as workhouse hospital nurses in 1861 at the Limerick Union workhouse. After protracted correspondence on the matter, the appointment of three of the order's nuns was reluctantly acceded to by IPLC so long as the posts were advertised and interviewed in normal manner and that the workhouse master retained overall responsibility for the infirmary's operation. There was also concern that such appointments did not result in demands for religious segregation within workhouse infirmaries. Within twenty years, the Irish Local Government Board was positively recommending the employment of Sisters of Mercy to provide workhouse medical care. A survey in 1903 revealed that 85 unions employed nuns as nurses, with the nursing matron in 32 workhouses being a nun. Nuns were also employed as teachers. In many cases, the nuns were given their own separate accommodation on workhouse sites.

Employment of nuns by Irish unions, 1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By the 1870s, as a result of all these changes, the level of medical care accessible by the Ireland's poor was several decades in advance of that in England and Wales. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the make-up of workhouse population reflected the changing role of the institution as shown in the chart below. By the end of the 1800s, around three quarters of the inmates were officially classified as sick or as 'other' - a group which probably comprised mostly the elderly and infirm.

Poor relief in Ireland, 1851-1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The above chart also shows a steady increase in the numbers receiving out-relief. The large increase in 1879-81 was due to an agricultural crisis caused by several years of bad weather and poor harvests which led to severe food shortages and unemployment, particularly in the west of Ireland.

Children in the Workhouse

As in England and Wales, there were efforts by the central authorities to reduce the numbers of children residing in Irish workhouses. By 1900, however, children still comprised almost one in seven of Ireland's 41,980 workhouse inmates. The removal of pauper children to other forms of accommodation such as cottage homes or scattered homes were not adopted by any Irish union. The setting up of District Schools, which had hadlimited take-up in England, was even less successful in Ireland with only two such schools being established — at Trim in 1890, and at Glin in 1893. The option that proved most popular with Irish Boards of Guardians was that of boarding-out of orphaned or abandoned children with foster parents. Boarding-out was introduced in 1862, initially in an attempt to reduce the mortality rates of those under five. The age limit for boarding-out was increased to ten in 1866, and to 15 in 1898. In 1900, a total of 2,223 children were being boarded out or 'out at nurse', although the majority of children remained in the workhouse.

Attempts at Reform

By the early 1900s, mounting criticism of the poor relief system led to two major reviews of its operation. In 1903, a Vice-Regal Commission was appointed to investigate whether financial savings could be made, and also whether improvements could be made in the ways that relief was provided in Ireland. Its report, published in 1906, proposed:

- The abolition of the workhouse system

- Placing various categories of inmates in separate institutions

- The creation of county almshouses for aged and infirm

- The development of the country's resources

The 1905 Royal Commission, examining the poor relief system throughout the British Isles, broadly reached the same conclusions, emphasising the need for classification by institution as well as within institutions. No new legislation directly resulted from the Commission's work, however, and the outbreak of the First World War brought other priorities to the fore. During the war, a number of workhouses were partly or entirely put at the disposal of the military authorities.

Independence

The Irish War of Independence culminated in the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6th December 1921. This created the independent Irish Free State containing twenty-six counties, while the remaining six (Armagh, Antrim, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone) stayed under British rule under the name of Northern Ireland. Following independence, Boards of Guardians were abolished and replaced by County Boards of Health or County Boards of Public Assistance.

Between June 1922 and May 1923, a further conflict took place in the form of the Irish Civil War. During this, and the previous struggles, many workhouses had undergone military occupation and had been damaged or burnt down. Of the remainder:

- 33 became County Homes offering relief to the elderly and chronic invalid

- 32 became District or Fever Hospitals

- 9 became County Hospitals

Bibliography

- Crossman, V (2006) Politics, Pauperism and Power in Late Nineteenth-century Ireland

- Gray, P (2009) The Making of the Irish Poor Law, 1815-43

- Hamrock, Ivor (ed) (1998) The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850 (Mayo County Council).

- Lewis, S (1837) A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland

- St Joseph's Hospital, Clonmel by Eamonn Lonergan (2000, published by author).

-

O'Connor, John (1995) The Workhouses of Ireland

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.