Entering and Leaving the Workhouse

Why Did People Enter the Workhouse?

People ended-up in the workhouse for a variety of reasons. Usually, it was because they were too poor, old or ill to support themselves. This may have resulted from such things as a lack of work during periods of high unemployment, or someone having no family willing or able to provide care for them when they became elderly or sick. Unmarried pregnant women were often disowned by their families and the workhouse was the only place they could go during and after the birth of their child. Prior to the establishment of public mental asylums in the mid-nineteenth century (and in some cases even after that), the mentally ill and mentally handicapped poor were often consigned to the workhouse. Workhouses, though, were never prisons, and entry into them was generally a voluntary although often painful decision. It also carried with it a change in legal status — until 1918, receipt of poor relief meant a loss of the right to vote.

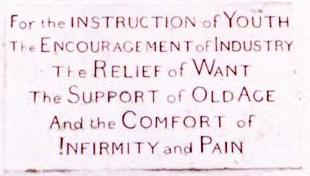

The operation of workhouses, and life and conditions inside them, varied over the centuries in the light of current legislation and economic and social conditions. The aims of many pre-1834 workhouses are well expressed in this 1776 sign above the door of Rollesby workhouse in Norfolk:

East & West Flegg workhouse, Rollesby, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The emphasis in earlier times was more towards the relief of destitution rather than deterrence of idleness which characterized many of the institutions set up under the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

Entering the Workhouse

Whatever the regime inside the workhouse, entering it would have been a distressing experience. New inmates would often have already been through a period of severe hardship. It was for good reason that the entrance to the Birmingham union workhouse was through an arch locally known as the "Archway of Tears".

Archway of Tears at Birmingham workhouse, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

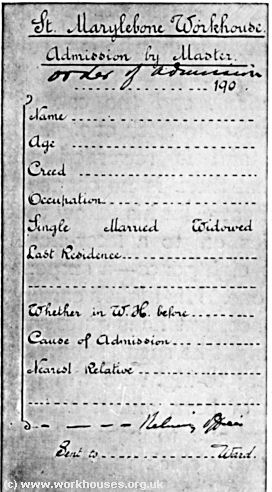

The Admission Procedure

Admission into the workhouse first required an interview to establish the applicant's circumstances. This was most often undertaken by a Relieving Officer who would visit each part of the union on a regular basis. However, the workhouse Master could also interview anyone in urgent need of relief.

St Marylebone workhouse Master's admission ticket, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

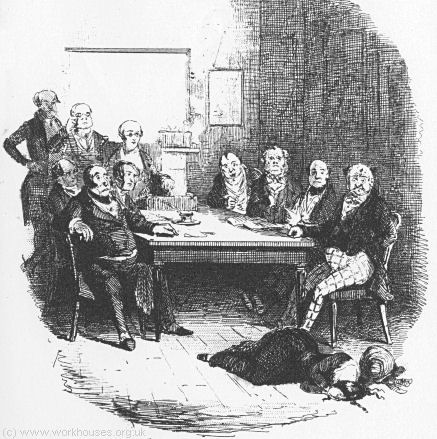

Formal admission into the workhouse proper was authorised by the Board of Guardians at their weekly meetings, where an applicant could summoned to justify their application. This would no doubt have been an intimidating experience — the heroine of the 1840s novel Jessie Phillips collapsed on the board-room floor. Half a century later, however, a cartoon in Punch showed how times and attitudes had changed in the intervening years.

Before the Board (from Jessie Phillips by Frances Trollope (1844).

© Peter Higginbotham.

Guardians' Interrogation (from Punch, 1899).

© Peter Higginbotham.

Prior to their formal admission into the main workhouse, new arrivals would be placed in a receiving or probationary ward. There the workhouse medical officer would examine them to check on their state of health. Those suffering from any infectious illness would be placed in a sick ward.

Each new arrival at the workhouse would go through a fairly involved admission procedure. After all the necessary paperwork had been completed, paupers were stripped, bathed, and issued with a workhouse uniform. Children (although not adults) could be required to have their hair cut. An inmate's own clothes would be washed and disinfected and then put into store along with any other possessions they had and only returned to them when they left the workhouse.

Liverpool inmates' bathing regulations

Leaving the Workhouse

While residing in a workhouse, paupers were not allowed out without permission. Short-term absence could be granted for various reasons, such as a parent attending their child's baptism, or to visit a sick or dying relative. Able-bodied inmates could also be allowed out to seek work. Although there was often little to physically prevent a pauper from walking out of the workhouse, to do so without permission would result in a charge of the theft of union property — his workhouse uniform. Any pauper could, however, on giving "reasonable notice" — typically three hours — discharge himself from the workhouse. His clothes would then be fetched from the store and more administrative paperwork would need to be completed. In the case of a man with a family, the whole family would have to leave if he left.

Despite the lengthy admission and discharge procedures, some paupers treated the workhouse as a free lodging, leaving and departing as the fancy took them. It was not unknown for a pauper to discharge himself in the morning and then return demanding re-admission the same evening, possibly the worse for wear from drink. In 1901, one 81-year-old woman named Julia Blumsun recorded 163 separate admissions to the City of London workhouse, while a 40-year-old man in the Poplar workhouse had been in and out 593 times over the period since 1884. These were the most extreme examples of what became known as the "ins-and-outs". Because of the amount of time they took to deal with, became the bane of the workhouse staff's life. Eventually, in the early 1900s, new regulations were introduced to lengthen the amount of notice required depending on how recently an inmate had previously discharged himself.

Perhaps a more typical example of the ins-and-outs is provided by seven-year-old Charlie Chaplin who in 1896 briefly became an inmate of the Lambeth union workhouse, together with his mother, Hannah, and his older half-brother Sydney. After a three-week probationary period, the two children were then transferred to the Central London District School at Hanwell. Two months later, the children were returned to the workhouse where they were met at the gate by Hannah, dressed in her own clothes. In desperation to see them, she had discharged herself from the workhouse, along with the children. After a day spent playing in Kennington park and visiting a coffee-shop, they returned to the workhouse and had to go through the whole admissions procedure once more, with the children again staying there for a probationary period before returning to Hanwell.

Many inmates were, however, to become long-term residents of the workhouse. A Parliamentary report of 1861 found that, nation-wide, over 20 percent of inmates had been in the workhouse for more than five years. These were mostly consisted of elderly, chronically sick, and mentally ill paupers. Fifteen inmates in the survey had been workhouse residents for sixty years or more. Institutionalization of inmates, particularly women, was something that was to continue right until the end of the workhouse era. In the past few years, whilst visiting a number of former workhouses that now operate as care homes for the elderly, I have been told on two separate occasions that one of the establishment's current residents had been there since the 1920s.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.