Rowton Houses

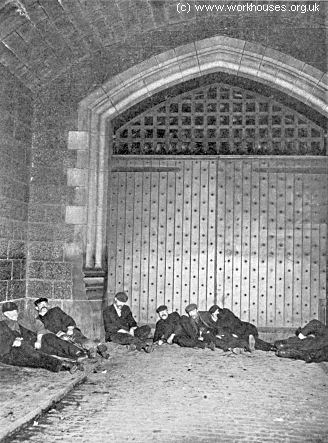

Until the 1890s, the main overnight accommodation options for down-and-outs in London were the various doss-houses, hostels and charity refuges, or the workhouse casual wards which were free but demanded a stint of manual labour in return for their very basic food and shelter. A final alternative, to which many resorted, was sleeping rough on the Embankment or on the bridges over the Thames.

Sleeping rough under Thames arches, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

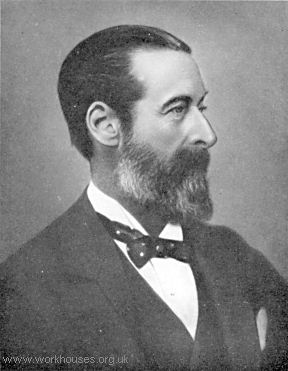

In 1892, a new type of accommodation appeared — the first of the "Rowton Houses" created by politician and philanthropist Lord Rowton (otherwise known as Montagu William Lowry Corry, or Monty Corry to his friends), a former private secretary to Benjamin Disraeli. In 1890, Rowton was involved in setting up the Guiness Trust which aimed to provide low-cost accommodation for working people in London and Dublin. As part of this project, he undertook a survey of the all the types of accommodation that existed in London's East End, including common lodging houses. As a result of this experience, Rowton decided to set up a new type of working men's hostel to give men a better, cleaner place to live. He put up the then enormous sum of £30,000 of his own money to finance the scheme. The hostel, with 470 bedded "cubicles", opened on 31st December 1892 at Bond Street (now Bondway) in Vauxhall.

Lord Rowton.

Lord Rowton.

Rowton took advice on the design of the building from Mr R.E. Farrant of the Artisans and Laborers' Dwellings Company who had a great deal of experience in he provision of dwellings for the poor. As a result, the new establishment contained many innovations for its day. In stark contrast to the squalid conditions of the casual ward and many common lodging houses, residents of the new "working-mans' hotel" were given clean sheets, the use of tiled wash rooms, footbaths, washing troughs and drying facilities for clothes, and ample supplies of hot water. The establishment also including a large dining-room and a library. On its first night of opening, only 77 beds were occupied, but the news soon spread about the undreamt of luxury to be had for 6d a night. In its first year of operation, a total of 140,105 beds were let, making the establishment a commercially profitable enterprise.

The Vauxhall Rowton House, 1895.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Vauxhall Rowton House, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

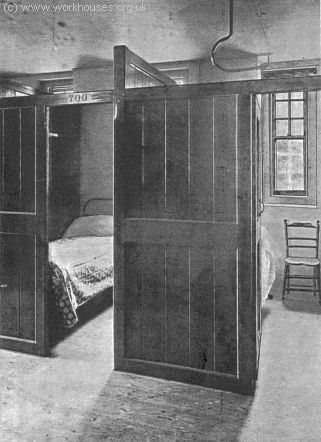

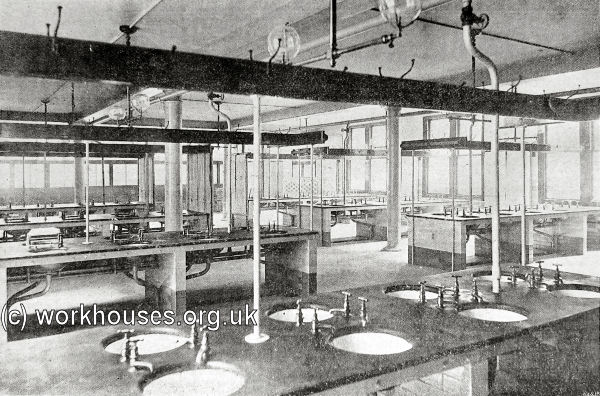

Rowton took a close and personal interest in every detail of the building, which he affectionately referred to as the "beehive". In the lavatory (washroom) the basins were amply spaced, and hooks provided above so that a man could hang his hat and coat high up above the basin so he could keep an eye on it. The furnishings were carefully chosen and Rowton even took one of the proposed beds home to test it out. Most of the beds were in single-bedded cubicles — a few multi-bedded rooms were originally included but proved unpopular and were soon converted to single ones.

Bedroom cubicle at Hammersmith Rowton House, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The new venture was not without teething problems. In its early days, the house had a high turnover of staff and the administration of the home was falling into chaos until a Superintendent, a former sergeant-major, was appointed. Within a few weeks of opening, every book in the house's library had disappeared, resulting in the installation of lockable bookcases under the charge of a paid librarian. At the first fire-drill, every copper coupling and nozzle from the fire hoses was found to have disappeared. Soap ceased to be provided for free after it was being consumed in prodigious quantities.

Washroom at Newington Rowton House, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1894, a company was formed under the name of Rowton Houses Ltd. to expand the scheme. The company initially had a capital of £75,000 which gradually increased to £450,000 by 1910. The company erected a total of six Rowton Houses in London:

- Vauxhall — on Bond Street (now Bondway). Opened 31st December 1892 with 470 beds.

- King's Cross — at corner of King's Cross Road and Calthorpe Street. Opened 1st February 1896 with 678 beds

- Newington — at Newington Butts, Elephant and Castle. Opened 23rd December 1897 with 804 beds.

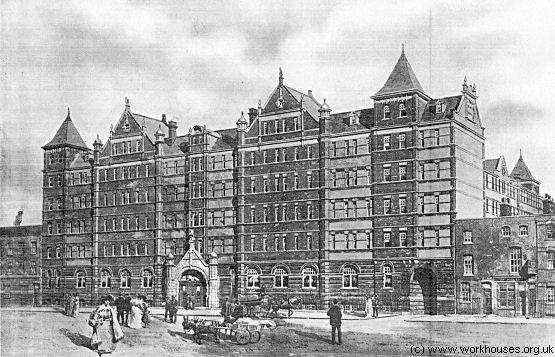

- Hammersmith — at 221 Hammersmith Road. Opened 2nd December 1899 with 800 beds.

- Whitechapel — at Fieldgate Street. Opened 11th August 1902 with 816 beds.

- Camden Town — at Arlington Road. Opened 7th December 1905 with 1103 beds.

A resident of the King's Cross House in 1899 described its facilities:

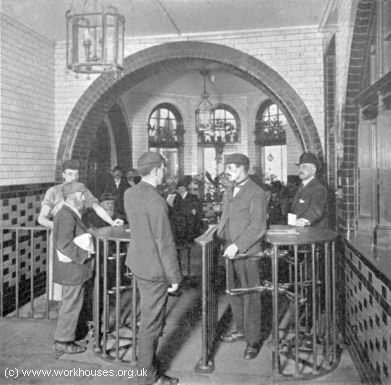

These gates are closed at nine-thirty in the morning, and kept, locked all day until seven-fifteen, when one of them is opened to admit the first batch of sleepers, mostly men who have to rise at three, four, or five in the morning—workers in the Smithfield Meat Market, sellers of newspapers, and workers among the vegetables in Covent Garden.

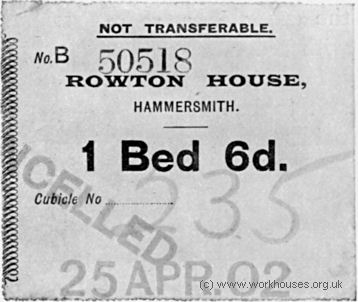

This gate is opened again every quarter of an hour, when a fresh batch of sleepers will have gathered at the gateway, where they have to show their cubicle ticket, which is marked by the attendant, or stamped 'cancelled' if their time has expired.

There are no appliances for washing on the cubicle floors. Washing is done on the ground floor. There are eighty wash-hand basins, with hot and cold water, towels hung upon rollers, and you supply your own soap.

There is a long; narrow room containing twelve large foot-baths in which the men may wash their feet.

And last—if it ever should be that the people for whom Lord Rowton has built these homes should wish to raise a tribute to his memory, let them carve at the base of its granite column that he gave them a bath, a clean towel, and soap for a penny.

And now we will pass to the breakfast and dining rooms. There are two rooms. The larger room contains thirty-eight tables made of oak, the smaller room nine tables—forty-seven tables in all. Four people can dine with comfort at each table, giving accommodation for one hundred and eighty-eight people at a time.

In the larger room there is a bar for the sale of provisions. At this bar there are three things they sell for a farthing—milk, matches, and vinegar. I bought a farthing's-worth of milk to use at breakfast this morning. For a halfpenny you can get a cup of tea, coffee, or cocoa, bread, watercress, onions in spring, marmalade, pickles, and butter. The articles to be purchased for a penny are too numerous to mention, but to-day you may get a small plate of cold meat, potatoes, and a salad of either cucumber or lettuce with tomatoes, the cost of which will be threepence. The working man dearly loves a salad. The walls of this room are hung with familiar engravings—Landseer's Horse-Shoeing', 'Elaine' ('the lily maid of Astolat'). In the smaller room the walls are brightened with chromolithographs—prominent among them Millais' 'Bubbles'.

There are two sitting-rooms, and in one of them a library, to which have recently been added two hundred and sixty new books, well printed and excellently selected. So far as my observation goes, Dumas seems to be most popular. I asked a workman the reason of this, and he answered: Because there's plenty of "go" about him.' Captain Marryat comes next—Midshipman Easy and delightful Peter Simple. Who would not be a boy again to read Peter Simple? But in this library there is one omission. Among these six hundred fellow-lodgers of mine, there are at times sorrowful people for whom there should have been provided a copy of Robinson Crusoe. You may play at draughts or chess, but cards are not permitted.

Hammersmith Rowton House, 1899.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Hammersmith Rowton had a similar range of facilities: dining-rooms, a smoking-room, a reading and writing room, bath-rooms, a shoemaker's shop, lodgers' store rooms and lockers — all on the ground floor or basement. Three stairways led to the cubicles above. As well as the lodgers bath-rooms, a special washhouse was provided for the use of lodgers wishing to wash their own clothes. The lavatory was a large room with forty basins. Adjoining it was a feet-washing room, with eight troughs divided by teak boards. At one side of the lavatory are the shoemaker's and tailor's shops, adjoining which a space has been specially fitted out for the lodgers to clean their clothes and boots.

Hammersmith Rowton House entrance hall, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hammersmith Rowton House courtyard, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Hammersmith House's reading room had tables which could seat 176, plus a number of easy chairs around its four fireplaces. The books were stored in cases with glass doors, so that the titles could easily be read from the outside. The room's superintendent had to be asked before a book could be removed from the shelves. The smoking-room, nearer to the entrance, had table space for 164 together with plenty of easy chairs. A large fire-place bay window gave a view into a courtyard. An open-air smoking-lounge, with a roof over it, occupied the frontage of the building opposite the dining-rooms. The two dining-rooms could seat a total of 464 men. In one of them was a shop where the lodgers could buy a wide range of eatables and drinkables, from sums ranging from a farthing to a penny. Four large cooking ranges, with ovens, hot-plates, and grills, were at the lodgers' service, and boiling water was always available for making tea. A scullery was placed between the two dining-rooms, so that lodgers who wished to prepare their own food for cooking to do so out of the dining-rooms. Another room was reserved for keeping crockery, cooking utensils, teapots, etc. Lodgers cooking their own food had free use of all the things here, and were not expected to clean them. The various articles were left in the dining-rooms after use, and afterwards collected by the attendants.

Hammersmith Rowton House dining-room, 1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The 800 sleeping cubicles were accommodated on five floors. Each had its own window, plus a chair, shelf, clothes hooks, and what was delicately described as a "utensil". The three fireproof staircases, two at the southern boundary of the site, and one adjoining the office, were all at the extreme ends of the cubicle corridors making it impossible to be trapped by fire. Each floor was also sub-divided by walls into eleven sections to check the spreading of a fire and also allowing isolation and efficient fumigation in the event of a case of contagious disease.

The Newington Rowton House, 1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Items such as tableware were specially produced for the Houses, all marked to identify them and to deter theft.

A Rowton pint mug and a vase produced for the Camden House.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The facilities were of such a standard that the Rowton Houses became officially categorised as "hotels" and therefore escaped the compulsory inspection that applied to common lodging houses. Even so, Jack London, on his undercover visit to London's East End in 1902, labeled the recently erected Whitechapel Rowton House as a "monster doss-house".

Tower House, Whitechapel — Jack London's "monster doss-house", c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The last of the London Rowton Houses to be built, and the largest, was at Arlington Road in Camden Town. Now known as Arlington House, it is still in use as a men's hostel. The building incorporated all of the usual Rowton House features. The upper floors had an E-shaped layout to maximise the use of available light, both in the dormitory cubicles and also in the basement via lantern windows in the ceilings.

The Camden Town Rowton House, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Camden Town Rowton House entrance floor plan, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Camden Town Rowton House lower ground floor plan, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Rowton House reading-room, 1930.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Later Developments

During the First World War, demand for the Houses accommodation initially declined as many of the normal residents, and the Houses' staff, joined up for military service. As the war progressed, the Houses provided emergency beds for refugees, and also accommodated detachments of troops. For a time, the Camden Town and Kings Cross Houses, were virtually taken over by contingents of the Royal Engineers. With the onset of German air-raids in 1915, the Houses also acted as informal air-raid shelters for women and children living in their vicinity.

After the war, demand for accommodation revived, with many ex-serviceman becoming residents. During the 1920s, the houses were modernized with electric light being installed and the old open fires being replaced by central heating. The lodgers' own kitchens, which had proved difficult to service and keep clean, were removed in 1924 although tea-making facilities were retained.

Rowton Houses featured in George Orwell's 1933 book Down and Out in Paris and London. By this date, the price of a cubicle had risen to a shilling.

'You men sleep 'ere last night?'

'No.'

'Then —off.'

We obeyed, and stood two more hours on the street corner. It was unpleasant, but it taught me not to use the expression 'street corner loafer', so I gained something from it.

The best [lodging houses] are the Rowton Houses, where the charge is a shilling, for which you get a cubicle to yourself, and the use of excellent bathrooms. You can also pay half a crown for a 'special', which is practically hotel accommodation. The Rowton Houses are splendid buildings, and the only objection to them is the strict discipline, with rules against cooking, card-playing, etc. Perhaps the best advertisement for the Rowton Houses is the fact that they are always full to overflowing.

During the Second World War, the Houses provided transit accommodation for evacuees en route to the countryside, and also for refugees from Poland and Belgium. As in the First World War, the buildings were also used as air-raid shelters and to house occasional parties of troops. The Houses suffered occasional bomb damage — in 1940, the Whitechapel House suffered a direct hit which destroyed a gable and damaged some top-floor walls.

In the 1950s, the Houses were increasingly occupied by the elderly of modest means for whom they offered a more attractive residence than other types of institutional home — one Kings' Cross resident lived in the house for 22 years. Some residents did seasonal work elsewhere during the spring and summer then returned to spend the autumn and winter in London. The Houses also received a certain number people referred by the National Assistance Board or by Probation Officers.

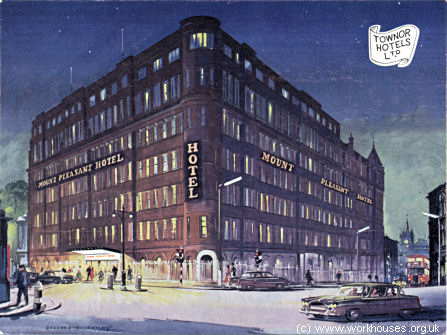

The King's Cross Rowton House continued in operation until 1960, by which time prices had risen to 3s.6d per night for a simple cubicle, to 4s.6d - 7s. per night for more comfortable bedrooms. Over its life it had provided over 20 million bookings. After a £300,000 refit, it re-opened on October 9th 1961 as the Mount Pleasant Hotel with 340 single and 82 double rooms, each equipped with a radio and telephone. A single room with bed and breakfast now cost 21s, or 35s. for full board. In 1967, the owners successfully sued the author, publisher and printers of Len Deighton's London Dossier which claimed that the hotel was "too expensive for place that used to be a hostel for down-and-outs". The book also described the remaining Rowton Houses as "grim places, echoing with the cries and coughs of defeated men."

A publicity shot of the former King's Cross Rowton House after its conversion to a hotel, c.1961.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The King's Cross, Hammersmith, and Newington Butts Rowton Houses have been demolished. The Vauxhall and Camden Town Houses are still used as hostel accommodation, while Whitechapel has now been refurbished for residential use.

Rowton Houses outside London

The Rowton Houses scheme was much copied. In January 1900, The Times reported on the opening of a Rowton-style hostel in Liverpool:

Yesterday afternoon the Earl of Derby opened at Liverpool a people's home something after the style of the Rowton house in London. It is calculated that about 14,000 persons seek single lodgings in Liverpool every night, while a great many of the lodgings which private adventure supplies are hardly worthy the name. The new building, "Bevington-house," is situate in Bevington-bush, and near the west side of St. Martin's Market, Scotland-road. Its accommodation is for single men, and comprises 500 cubicles, or sleeping apartments. There are two large kitchens, with a number of cooking stoves, and the lodgers may bring in their own victuals and cook them or may purchase them at cost price. Close by is a large dining-room, as well as reading and recreation rooms. In the basement are large apartments, which, like the staircase, are lined with vari-coloured glazed bricks. Here are the resources for washing and the repairing of clothes, which may be done by the men themselves or by tailors and shoemakers. Each sleeping apartment is 7ft. 6in. by 5ft., and in each is an iron bedstead, with copper wire mattress, a hair mattress, two hair bolsters, two sheets, pillow, under blanket, three over blankets, and a counterpane. There is a chair by the bedside, and a small window to light the room. There is an outdoor promenade, with pot plants and seats. The nightly charge for a cubicle, with the use of the other resources of the home, is 6d. The whole cost of the building is stated at £25,000. At the rear is about 800 yards of land which may be utilized for extension. The home was built by a company, the directors of which are Lord Mayor Cohen, Colonel G. H. Morrison, Mr. Archibald Williamson, Mr. George Banner, Mr. John Henderson, and Mr. A. A. Paton, all prominent local men interested in the problem of housing the poor and providing lodgings for the unmarried work-people and doing what they can to make this experiment a success. The foundation was laid some 18 months ago by the late Mr. Ismay, one of the greatest and best of Liverpool's citizens.

Mr. ARCHIBALD WILLIAMSON said that a House for women was also in contemplation, but the means did not run to that yet. LORD DERRY, in declaring the building opened, said he had the greatest pleasure in seeing such a fine building erected with such an excellent combination of philanthropy and business. That was the one great privilege, perhaps hardly enough understood at the time, with which his old friend Lord Rowton founded the homes in London. To have provided accommodation for 450 people, with a possibility of raising the number to 600, in a district of that kind was an honour to the town itself and must confer most inestimable advantages, and he congratulated all concerned on an experiment which, he believed, was calculated to promote the prosperity of the country and the better and happier life of their fellow men.

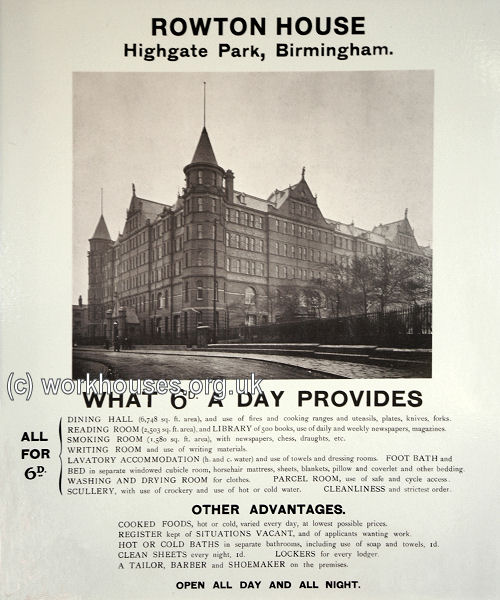

A "Rowton House" was erected in on Alcester Street, Highgate Park, Birmingham in 1903. It was operated by locally formed company but used the same architect, Harry Bell Measures, who had designed the London Houses. It followed the design used at Camden and Hammersmith — a U-shaped building with lantern windows in the centre of the "U" providing light to the lower floors. The Birmingham Rowton House could accommodate 819 men who paid 6d. a night for one of its bed cubicles.

The Birmingham Rowton House.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Birmingham Rowton House, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

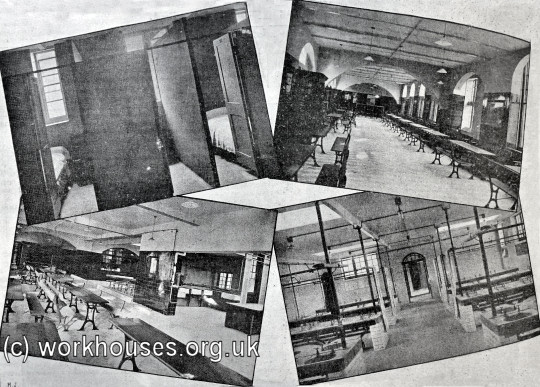

In 1903, the London County Council erected Carrington House in Deptford, closely modeled on the Rowton House designs. This was so much so that the invitations to its official opening described it as a "Rowton House known as Carrington House". Following the opening of Carrington House, around a hundred men left Newington Butts for Deptford which was nearer to their work. However, within a few weeks, all had returned to the Rowton House which they said was "more homely, more comfortable and warmer". The Rowton Houses continued to be full each night, while Carrington House was usually half empty.

Carrington House, Deptford, c.1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Carrington House interiors, c.1903.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A Rowton-type hostel was opened in the early 1900s on Dog Bank in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It was subsequently taken over by the Salvation Army as a "Men's Palace". A Rowton-style establishment was built in 1913 on West Bar in Sheffield.

Sheffield's Rowton House, 2010.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Similar Rowton-style homes were set up further afield, such as the Mannheim in Vienna and the Hotel Pour Les Hommes in Paris. In 1901, The Times described an establishment in Milan.

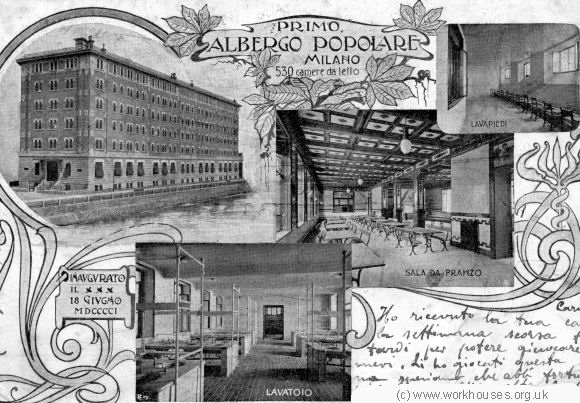

The finished building, the "Albergo Poplare", was opened on June 18th 1901 with a complement of 530 rooms, plus the usual communal facilities such as dining hall (Sala da Pranzo), wash-room (Lavatoio), and foot-washing room (Lavapiedi).

Milan's "Albergo Popolare", c.1912.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bibliography

- Sommerville, W.A. (1899) Rowton House — from a Resident

- Cornes, James (1905) Modern Housing in Town & Country (London: Batsford)

- Deighton, Len (1967) Len Deighton's London Dossier (London: Cape)

- Farrant, Richard (1904) Lord Rowton and Rowton Houses in Cornhill Magazine, June 1904.

- Sheridan, Michael (1956) Rowton Houses 1892-1954 (London: Rowton Houses Ltd)

Links

Individual Rowton Houses:

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.