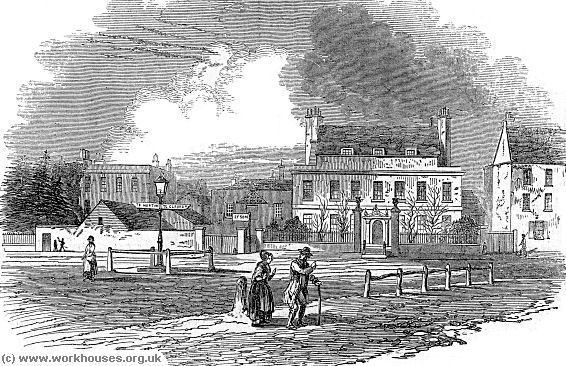

Mr Drouet's Establishment for Pauper Children, Tooting

Mr Drouet's Establishment at Surrey Hall, Lower Tooting was a privately operated residential school for pauper children located around eight miles to south-west of London. A school was first opened on the site in 1804 by William Bicknell who ran it until his retirement in 1813. After Bicknell's death in 1825, Surrey Hall was acquired by the Drouet family and the school was taken over by Bartholomew Peter Drouet. Drouet turned the school into an establishment for "farming" pauper children from London parishes who, following Hanway's Act of 1767, were required to reside at least three miles from the capital until they attained the age of six. Although Hanway's Act was repealed in 1844, Drouet's and similar establishments continued in operation for a further five years, taking pauper children up to the age of fourteen when they could earn their own living. Such schools provided a modest degree of formal education but, outside of school-hours, children were employed at menial tasks such as oakum picking and sorting bristles. In 1839, the Poor Law Commissioners requested Drouet's school, and another in Norwood run by Mr Aubin, to enhance their teaching and to introduce industrial training to try and better equip their children for self sufficiency in later life.

An official report for the Poor Law Commissioners in 1846 noted that 723 children were in residence at the Tooting school, placed there by the parishes of St George-in-the-East, St Martin-in-the-Fields, Chelsea St Luke's, and Newington St Mary, and the Richmond and Strand unions. The charge made for each child was 4s.6d. per week, including clothing.

The boys' school was run by a Mr Harding plus two assistants and accommodated over 200 in a room 52 feet by 21 feet, thus giving around six square feet per child.

The girls' school was taught by a mistress with an assistant and 13 monitors selected from the top class. The seven-and-a-half hours of school time each week were taken up with writing (three hours), singing (one-and-a-half hours), and the remainder in reading, spelling and ciphering. Needle-work was carried out for four-and-a-half hours a day during the week, mostly in making shirts, of which around six hundred per week were produced. Some of the girls helped with various household duties

Mr Drouet's Establishment, 1849

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Tooting Cholera Disaster

By 1848, Mr Drouet had almost doubled the number of residents at his establishment to just under 1400, and now also took children from the Holborn and St Pancras unions. In January 1849, the school became the centre of a scandal when a cholera epidemic broke out with the eventual death toll reaching 180. The school was visited on 2nd January by a party from St Pancras Guardians, with several doctors in attendance. An examination of the buildings, the general habits of the children together with their food, water, eating utensils and so on, led the medical men to pronounce that Mr Drouet had done everything in his power to allay the disease which was probably caused by an "atmospheric poison". Drouet was commended for the measures he had adopted for the comfort of those afflicted, and for the safety of the other children.

The establishment was visited on Friday January 5th and several successive days by Dr RD Grainger, an inspector for the recently created Board of Health which, at the time, had only limited powers in and around the metropolis. His report was critical of conditions at Tooting and ascribed overcrowding as one of the main contributory factors in the spread of the disease and that the school should be evacuated as soon as possible. An abbreviated version his report is included below:

I recommended earnestly that the number of nurses should be increased, and that each patient should occupy a separate bed. I found on Saturday that the proprietor of the establishment had not added a single nurse; so that the only addition made since Friday consisted of two women, who had been sent from St. Pancras; and yet at this time there were 179 cholera patients under treatment, being an increase since the Friday of no less than sixty-four. I found four of the female wards under the care of only one nurse.

An attempt was made to make up for this insufficient supply of nurses, by employing some of the older pauper boys and girls still free from attack; in one of the boys' wards I found, for example, four boys of the average age of thirteen thus assisting ; even some of the children recovering from cholera were so employed. The consequence of all this inexcusable neglect was, that on Sunday the bed-clothes were still soaked with the evacuations of the suffering children, and that the few purses who were in the wards were obliged to run from one bed to another, and that the patients were most inefficiently attended.

I found only one resident medical officer, who had been the medical attendant of the establishment during the last two months, having to take charge of 1,370 children, at the remuneration of £50 a year, with board and lodging. It appears that a significant warning of the outbreak was given fourteen days before a single case occurred ; but not being understood, no preventive measures were adopted. It appears from the evidence, that after the attack of cholera no efficient means were adopted either to discover the existence of the premonitory diarrhoea, or for its treatment when it was brought under the notice of the resident medical officer.

On examining the buildings appropriated to the children in general, I found that most unfavourable arrangements existed both as regards light and air. In the schoolroom for boys the master informed me there were, when all were present, 500; the length of the room being 94 feet, the width 21 feet, and the height 11 feet. The ventilation is most defective, and entirely incompatible with the maintenance of health, even in the case of a much smaller number of boys than that above specified.

About five or six months ago a low range of building, constituting one long room, was erected in the immediate vicinity of a yard, in which a large number of animals, pigs, cows, horses, and poultry, are kept. These premises are, moreover, in a more objectionable situation, as they are placed very near to the two foul open ditches or drains. Notwithstanding a representation to the contrary from a late medical attendant of Mr. Drouet's establishment, 150 children were placed in the room.

The numerous open ditches, canals, and pieces of water of the most offensive diameter, in the neighbourhood of the establishment, render the locality totally unfit for the lodgment of a large number of children, and the pure air of the country only has hitherto kept away violent epidemic diseases. This injurious locality, however, has only played a secondary and indirect part in the epidemic. The essential causes of the outbreak must be sought in the establishment itself, And, first, as regards the diet:— This consists of meat three times a week... In many instances the food has been defective in quality; the kind and quality of the diet also have been of an objectionable character, and liable, especially in a season like the present, to have exerted an injurious influence on the system. It is much to be regretted that the proprietor did not, in accordance with the recommendations issued by the General Board, discontinue the use of a vegetable diet; if, instead of feeding these children so often on a kind of food, pease-soup (known to exert in many case a relaxing influence on the alimentary canal), a diet consisting more of solid, dry and farinaceous food, had been substituted for green vegetables.

After maturely considering all the circumstances connected with the painful occurrence, I am induced to express my firm conviction that the essential cause of all the mischief has been the inordinate overcrowding of this establishment.

Grainger's recommendation was taken up by most of the school's patrons — by the 10th January, around a thousand children had been removed. The Poor Law Board, however, argued against evacuation and persuaded the Chelsea union to leave their children in residence and to offer additional nursing and medical assistance to the school.

Further revelations about the school were made in a series of inquests initiated by Thomas Wakley, editor of the medical journal The Lancet and coroner for the county of Middlesex within whose jurisdiction some of the dead children came. The inquests held at Chelsea, St Pancras, Hackney and Kensington recorded various verdicts to the effect that the victims had died of the effects of cholera, aggravated by inadequate food and warm clothing, overcrowding, and poor ventilation. However, it was at the inquest held at the Royal Free Hospital, where sick children belonging to the Holborn union had been taken, that produced the most sensational outcome. The proceedings were held with Wakley as the presiding coroner.

A succession of witnesses revealed that the children at Drouet's establishment were regularly underfed or given poor quality food. One member of the Holborn Guardians, Mr W Winch, gave evidence about visits to the school during the previous year:

Several of the school's children gave testimony at the inquest. Patrick Sheen said that he shared a bed with two other boys. He never had enough to eat but was frightened of being beaten if he said so. Boys from St Pancras who had run away had been birched and then dressed in girls' clothes for several days as punishment. Henry Hartshorn, one of the boys who had raised his hand during the visit from the Holborn Guardians, earned a small amount of money shoemaking — a penny for each five pairs of slippers. Because he received so little food he spent the money on sweets, apples and pears sold to the children by the school's nurses and also paid ½d for water because not enough was provided.

The physical conditions at the school and Drouet's behaviour following the beginning of the cholera outbreak were also examined. It was noted that not a single case of the disease had occurred at Tooting outside the confines of the home. Drouet was said to have been dilatory in reporting the problem to the authorities and in obtaining medical assistance which could have saved many of the children's lives. It was noted that of the 155 children who had been removed to the Royal Free Hospital, not a single one had died, whilst many who had remained had since succumbed to the disease.

The verdict delivered by the inquest jury was that Drouet was guilty of manslaughter, and that the Guardians of the Holborn union had acted negligently in their dealings with him and in their inspections of his establishment.

As a result of the inquest's verdict, Drouet faced a criminal trial for manslaughter which began its proceedings at the Central Criminal Court of 26th February 1849. The case was brought in the form of a specimen charge relating to the death of James Andrews and three other children from the Holborn Union. The full indictment was that Drouet "contrary to his duty, had neglected to give the child proper food and sustenance, and had also neglected to provide it with wholesome and properly ventilated sleeping accommodation, and by these means had caused it to be mortally sick and distempered, and had so occasioned its death." The hearing began with a speech by the Recorder of the City of London, Charles Ewan Law, who warned the jury that much of the evidence previously presented at the inquests into the events at Tooting was based on hearsay and speculation and probably not admissible as legal evidence. The central question, as he saw it, was what specific act (if any) by the accused had led to the child's death.

Despite the apparent weight of evidence showing Drouet's negligent treatment of the children in his care, the defence successfully argued that there was no absolute proof that the child would have recovered if it had not been for Drouet's actions. On April 16th, following instruction from the judge, Mr Baron Platt, that there was no case to answer, the jury returned a not guilty verdict.

Drouet died in Margate at the end of July, 1849, following several months' illness.

Charles Dickens' Commentary on the Disaster

The events at Tooting, and Drouet's subsequent trial, were the subject of four pieces by Charles Dickens published (anonymously) in the weekly journal The Examiner between January and April 1849. Dickens is unstintingly critical of Drouet, the various Boards of Guardians who used his school, the London Recorder, and the judge presiding at Drouet's trial. The conclusion of his first article, published on 20th January, gives the flavour of his venom:

You can read the full text of Dickens' Examiner articles using the links below.

Bibliography

- Brice, AWC (1968) Dickens and the Tooting Disaster (in Victorian Studies vol 12, no. 2, December 1968).>

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.