Salvation Army Establishments

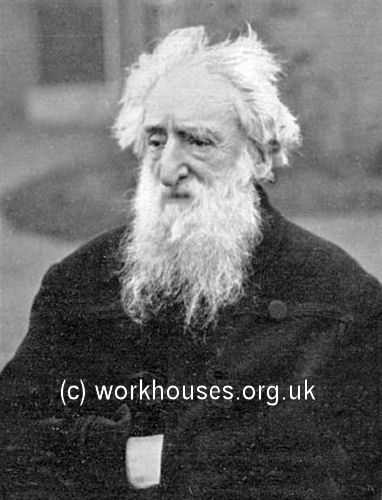

In 1865, William Booth founded an Evangelical Christian movement in the East End of London. Originally known as the Christian Revival Association, it was renamed in 1870 to become the East London Christian Mission, subsequently shortened to the Christian Mission. The group was reorganised and renamed in 1878 to become the Salvation Army — affectionately known as the "Sally Ann". The Army, with "General" Booth at its head, adopted a military-style uniform and "Articles of War" which included the renouncing of the use of alcohol. The Army also eschewed religious sacraments such as baptism and communion, considering them unnecessary.

William Booth, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hanbury Street Women's Shelter

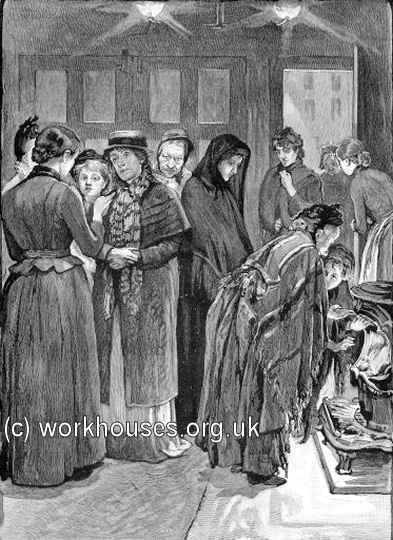

In addition to its religious crusading, the Army gradually became involved a variety of social welfare activities. One of the earliest, in May 1884, was a women's refuge at 212 Hanbury Street in Whitechapel, opened as part of a campaign to rescue young women from prostitution. This was replaced in 1885 by larger premises at 48 Navarino Road, Dalston. A new women's shelter was opened at 194 Hanbury Street — the extracts below from a 1891 account of a visit to the establishment give a flavour of its operation:

Hard as it is to reclaim these fallen women while they are young and pretty, and their sorry "trade" gives them meat and drink and the coarse pleasures of the gin-shop and the streets, there are some who come over — who regain their self-respect through their "conversion" —and who, falling prone as outcast sinners, rise redeemed as penitent Magdalenes. For such as these the Salvation Army has ever a glad welcome and a free pass; and, we venture to add, a more rational way of dealing with them than is to be found in the strict seclusion and dull monotony of many penitential Homes.

Hanbury Street Shelter — "A straight talk to an applicant", 1891.

© Peter Higginbotham.

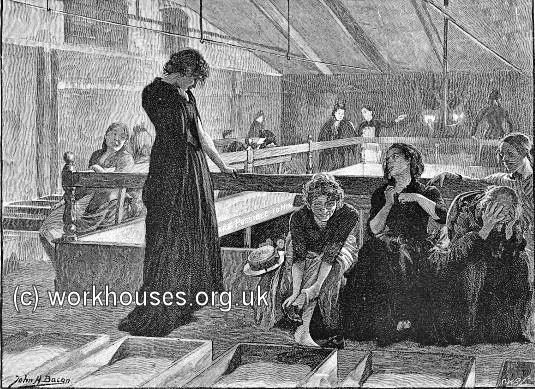

Hanbury Street Shelter dormitory, 1891.

© Peter Higginbotham.

During the year, 58,636 persons were supplied with lodging, supper, and breakfast, while a total of 2 5,41 2 meals were supplied. A total of 770 women were " assisted in their outward circumstances," such assistance including the reconciliation of wives with husbands, and the restoration of girls to their parents.

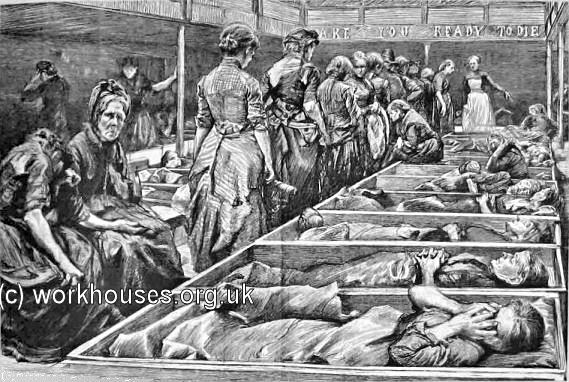

Hanbury Street Shelter dormitory, 1892.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In Darkest England

In 1888, after witnessing the large numbers of men sleeping rough on bridges over the Thames, Booth began to turn the Army's attention towards assisting the homeless. Sleeping rough was, at this date, an offence under the 1824 Vagrancy Act. Although the police sometimes turned a blind eye to it, prosecutions were frequently brought. However, the offence of "wandering abroad" required that a person was "without visible means of subsistence" so it was common practice for vagrants to carry a penny in order to circumvent such a charge. It was to help this homeless population that the Army began operating night shelters and food depots, where basic food and shelter could be obtained for as little as a penny a night. As well as the cost being low, partakers were treated with kindness and respect, unlike the reception usually provided at the workhouse casual ward.

In 1890, Booth published his book In Darkest England and the Way Out which documented the appalling conditions in which many of London's poor lived. His estimates of the numbers of the very poor, starving, and destitute that were living in London made salutary reading.

| East London | Estimate for rest of London | Total | |

| PAUPERS Inmates of Workhouses, Asylums, and Hospitals | 17,000 | 34,000 | 51,000 |

| HOMELESS Loafers, Casuals, and some Criminals | 11,000 | 22,000 | 33,000 |

| STARVING Casual earnings between 18s per week and chronic want | 100,000 | 200,000 | 300,000 |

| THE VERY POOR Intermittent earnings 18s. to 21s. per week. | 74,000 | 148,000 | 222,000 |

| Small regular earnings 18s. to 21s. per week. | 129,000 | 258,000 | 387,000 |

| ________ | ________ | ________ | |

| 331,000 | 662,000 | 993,000 |

Nationwide, Booth claimed that the total of what he called the "submerged classes" numbered around three million, or one in ten of the population — "the submerged tenth".

In his book, Booth outlined a new "social scheme" which outlined a number of practical ways that the poor could be helped. Booth proposed three types of community or "colony" be created:

- The City Colony — to "gather up the poor destitute creatures, supply their immediate pressing necessities, furnish temporary employment, inspire them with hope for the future, and commence at once a course of regeneration by moral and religious influences."

- The Farm Colony — "this would consist of a settlement of the Colonists on an estate in the provinces, in the culture of which they would find employment and obtain support."

- The Over-Sea Colony — "in our Colonies in South Africa, Canada, Western Australia and elsewhere, there are millions of acres of useful land to be obtained almost for the asking... We propose to secure a tract of land in one of these countries... settling it gradually with a prepared people, and so create a home for these destitute multitudes.

Following the enormous success of the book, and the income it generated from sales and from donations, the Army began to put the scheme into practice. A wide variety of social care establishments were opened, initially in London and later spreading to many other towns and cities in Britain and around the world. The City Colony included many further night shelters and food depots, working men's homes or hostels, factories and paper salvage plants, workshops for the unemployed, homes for single mothers, inebriates and ex-prisoners, and so on.

Night Shelters

The Army's first night shelter had been opened in 1888 in premises at 21 West India Dock Road in Limehouse. It was soon followed by others at 61A St John's Square, Clerkenwell; 272 Whitechapel Road, Whitechapel; and at 83 Horseferry Road, Westminster. The shelters provided a warm place to sit for the night with some little refreshment for a penny. Soup and bread were also on offer at a similar cost. During 1891, these four establishments provided a total of 208,019 beds and meals.

For those with a little more money to spare, "The Ark" at 96 Southwark Street was opened in January 1891, followed two months later by "The Harbour" at 9-10 Stanhope Street, Drury Lane. At these "working man's hotels" (or "metropoles" as they were known from 1891), a bed in a 4-bedded room cost 4d, while a separate cubicle cost 6d. A kitchen, dining-room, and coffee bar were also provided. A supper of bread, cold meat and tea cost 3d. Residents could come and go as they pleased up until midnight. In their first year, a total of 50,000 bed places were provided.

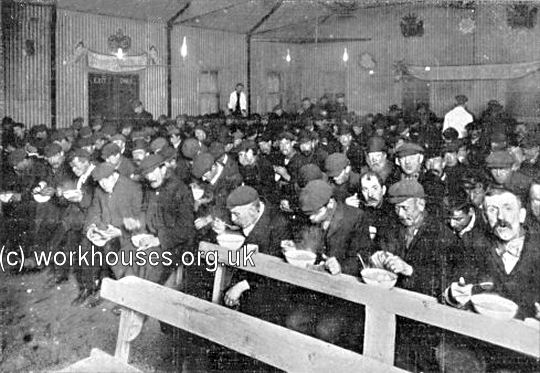

The night shelters generally opened at 5 p.m. and served supper at 7 p.m. Between 7 and 8 p.m. a "bright, simple meeting" was held through which the Army hoped to find converts to the Christian faith — in 1891, a total of 708 were recorded as having done so.

In 1889, a women's shelter was opened at 194 Hanbury Street in Whitechapel. It provided beds for up to 261 women, originally at a charge of 2d. a night, later raised to 3d. after the London County Council made the provision of sheets etc. compulsory. The shelter catered mainly for aged women, although a separate area was provided for women with children, each of whom was charged 1½d. per night. A kitchen dispensed large mugs of tea for ½d. and a chunk of bread for a second ½d. The main dormitory in the shelter had previously bee a swimming-bath. In 1910, some of the shelter's patrons were reckoned to have used the shelter almost every night for twenty years, while others used it for a period and then vanished, especially in the summer, to go hop or strawberry picking. The shelter continued in use until 1931 when its operation moved to new premises in a former LCC school on Finch Street. The shelter, and also Finch Street itself, were renamed Hope Town.

In 1891, unusually high levels of unemployment, and a subsequent increase in the homeless population, led to the Army setting up special relief stations at Poplar, Limehouse, Bethnal Green, Whitechapel, Rotherhithe, Deptford, and the Borough. At their peak of operation, the stations were dispensing up to 1,800 half-quartern loaves per day, plus an enormous quantity of cheese.

Many down-and-outs made their first acquaintance with the Salvation Army at its shelter (known as The Embankment)at 115B Blackfriars Road, just to the north of the Surrey Theatre. The shelter offered bunks, together with washing and kitchen facilities, at 3d a night. Alternative, in a long benched hall, a "penny sit-up" provided a night in the warm together with bread and soup.

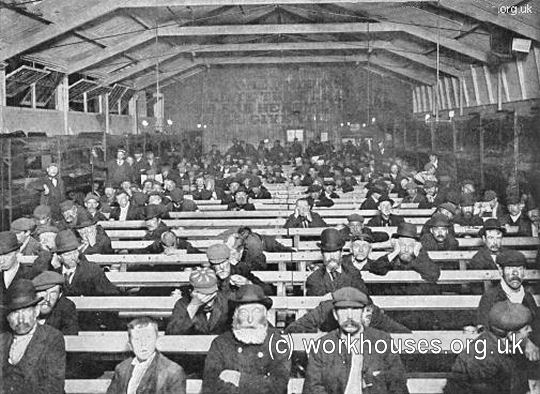

The Penny Sit-up at Blackfriars, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

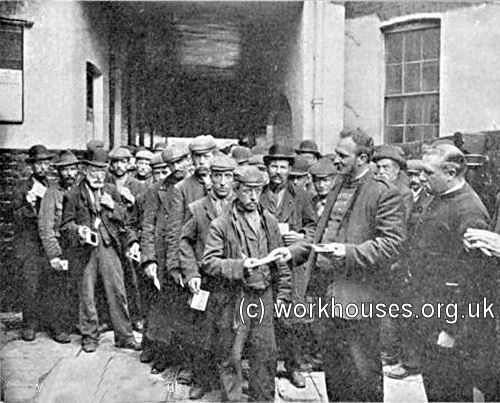

At night, Army members sought out those sleeping rough and offered them a voucher for a free breakfast at the shelter in return for attendance at an Army church service afterwards.

Queueing for the free breakfast service, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Queueing for the free breakfast service, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

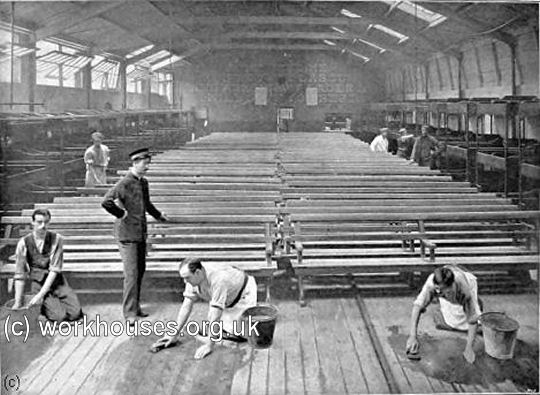

The Blackfriars Shelter being cleaned, c.1897.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Further Army shelters in London were subsequently set up at: 119-121 Green Street, Bethnal Green; 51-53 Royal Mint Street; 2 Burne Street, Edgware Road; ; 96 Southwark Street; Lisson Street, Lisson Grove; and 25 Charles Street, Farringdon Road. Additional working man's hotels included The Lighthouse at 41A Quaker Street, Commercial Street, Whitechapel; 30 Argyle Square, King's Cross; and 122 Spa Road, Bermondsey. A shelter for boys was located at 31 Fetter Lane.

The Army's shelters were not without opposition from local authorities who pressed for them to be regulated under the same terms as common lodging houses with regard to registering occupants, overcrowding and sanitary arrangements. Fears were raised about the shelters being breeding grounds for smallpox. The not-for-profit status of the shelters allowed them to escape such regulations and official inspection. In 1895, however, the Southwark Vestry successfully pressed for the capacity of the Blackfriars shelter to be reduced from 800 to 550 with the result that 250 men were turned out onto the streets in the depths of winter. It was not until 1936 that the Army's shelters and other similar establishments were placed under the same legal status as privately operated lodging houses.

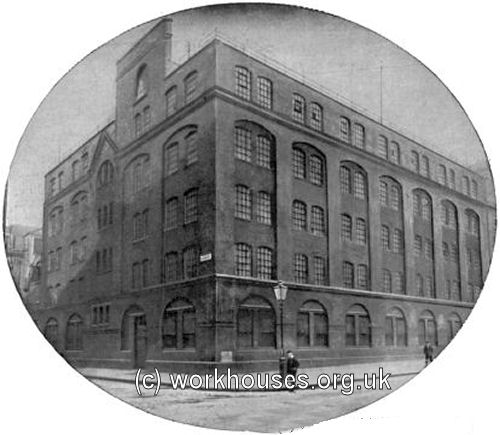

In 1906, a large "working men's hotel and shelter" was opened at 116 Middlesex Street. The six-floor building had sleeping accommodation for 462 men, of whom 311 paid 3d for a bunk bedstead with sheets and an American cloth cover. The remainder paid and extra 2d for a proper bed, fitted with a wire spring hospital frame and provided with a mattress, sheets, pillow, and blankets. For a further 1d, the inmates could obtain a good supper, consisting of a pint of soup and large piece of bread, or of bread and jam and tea, or of potato pie. A second penny supplied them with a breakfast the following morning consisting bread and porridge, or bread and fish, with tea or coffee. As well as a dining-room and sitting room, the occupants were also well provided with lavatories (washrooms) and bathrooms, and also facilities for washing and drying clothes. The basement of the building, with its own entrance, had a large hall. This opened at 5.30 p.m. to provide a free "sit-up" shelter with bread and soup provided for men found sleeping on the Embankment. The hall was also used for the holding of religious meetings.

Midnight soup for men brought in from the streets, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1909, to try and deal with the continuing large numbers of men who were sleeping rough in areas such as the Embankment, the Army took over a large former billiard works on Great Peter Street in Westminster for use as a men's shelter. After its conversion, it provided large dormitories which could hold a total of 600 sleepers, together with bathrooms, lavatories, kitchens, sitting rooms and smoking rooms. The charge for a night's accommodation was 3d. while a portion food cost either a penny or a halfpenny. Each night, between midnight and 6 a.m., the shelter received between 1,000 and 1,250 further men who were give free bread and soup, a seat on a wooden bench, and a breakfast of porridge and treacle before they left.

The Great Peter Street Shelter, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Outside London, men's shelters were established in Bradford and Bristol in 1891, followed by others at Manchester, Belfast, Bolton, Glasgow, Southampton, Birmingham, Halifax, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and Sheffield.

The first women's shelter outside London opened its doors in Cardiff in September 1891 and could accommodate 40 with some separate rooms as well as dormitory beds. A women's shelter for up to 70 opened in Edinburgh in 1893, with a similar establishment opening in Glasgow in 1896.

Elevators

An important part of Booth's City Colony proposals was the provision of work for the destitute so that in the short-term they could pay their way for their board and lodging, and in the longer term acquire useful skills to allow them to find permanent employment. To this end, the Army created establishments known as "Elevators" which combined a factory space together with hostel-type accommodation for those working there.

The first Elevator to be set up was at 159 Hanbury Street in Whitechapel — opposite the women's shelter at number 194. It began operation on 29th June 1890, prior to the publication of In Darkest England. By March 1891, two more had been opened at Fieldgate Street and at Old Street, and by the end of that year a further three were established at Leeds, Bradford and Bristol.

The work performed by the Elevators varied. Over the years it included: basket- and brush-making, carpentry, joinery and cabinet-making, french-polishing, tin-smithing, tambourine making, carpet-weaving, mat-making, mattress-making, sign-writing, wood-carving, firewood-chopping, tailoring, bakery, and sandwich-board carrying. Some Elevators were dedicated to the processing and recycling of household salvage, particularly waste-paper. Paper salvage was carried out by the Elevators at 18-22 Northdown Street, King's Cross; at Garrett Street, Whitecross Street, St Luke's; and at 122 Spa Road, Bermondsey, which became the headquarters for the salvage work.

The Spa Road Elevator, a former warehouse, was opened by General Booth in October 1896. It was converted to provide "a place for work by day and clean, well-ventilated and commodious rooms at night" for up to fifty men. A four-storey extension was opened in December 1911 which contained a dining hall to seat 500, two dormitories with space for 250 beds, and a hall that could hold 800. At this date, Spa Road employed 600 men and Garrett Street 200. These two Elevators output around 500 tons of waste paper per week. In their first week, men taken on at Spa Road received only their board and lodging in return for their work. In the second week, they received sixpence in cash, with amount increasing as they became more proficient. Some men could eventually earn eight or nine shillings a week, in addition to their board and lodging.

Sorting paper in an Elevator, c.1909..

© Peter Higginbotham.

A dormitory in an Elevator, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Some of the payments to Elevator workers and others was in the form of specially minted tokens which could only be spent at certain places — this was aimed at preventing wages being spent on things such as alcohol. The example below bears the letters "F.S." standing for Food and Shelter.

Salvation Army 4d Token.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1891, a salvage wharf was set up alongside the Thames at Battersea, announcing itself on a huge river-front sign as "Darkest England Salvage Convertor". As well as large amounts of waste paper, the wharf converted old tin-cans into toys, and repaired and cleaned old clothes, many of which were then used by Elevator workers or by needy women and children in the slums.

The Hanbury Street Workshop

The Elevator at 159 Hanbury Street was designated as a carpentry and joinery workshop and tin-works, although a variety of other crafts were carried out there. It was set up to assist tradesmen who had fallen on hard times by giving them temporary work until they could find other situations. In the early 1900s, up to fifty were employed at any one time, with between 100 and 150 men were passing through the workshop each year. Many of these were elderly and had difficulty in finding new employment so often stayed on at the workshop for rather longer than the Army would have hoped for. Such men invariably arrived in a state of complete destitution, even having sold their tools.

Much of the work produced by the workshop was for use by other branches of the Army. This included seats for use in the numerous Army halls, mattresses and mattress covers for Army shelters, and poultry-house for use at the Army's small-holdings scheme at Boxted.

The Hanbury Street Workshop was the subject of press criticism for paying the men employed there less than the normal Trade Union wage rates, contrary to its declared opposition to "sweated labour". The Army's response was that the work done by such men was often less than competent, and some were practically useless due to the effects of drink or other debaucheries. Many of the men would find it totally impossible to gain employment elsewhere. However, they were all paid in proportion the quality of their work, in addition to which many were provided with board and lodging. In 1909, wages ranged between 3s. per week plus board and lodging, up 45s. 11d. per week for two experienced men who were living out. The workshop consistently ran at a loss.

The Knitting Home

A Knitting Home (or Factory) operated at 122 Lower Clapton Road.

Salvation Army knitting factory., c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

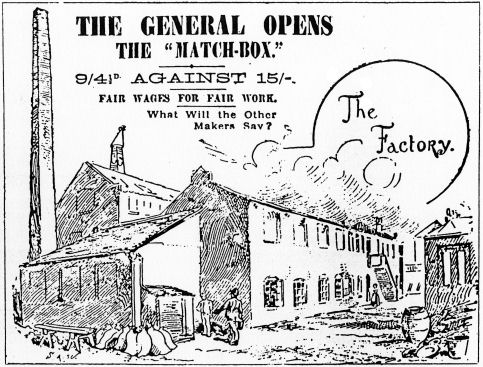

The Match Factory

On 11th May, 1891, General Booth opened a "Darkest England" match factory at Lamprell Street in Old Ford, to the north of Bow. It was set up to fight two industrial evils of the time which were prevalent in the industry. The first was the use of yellow phosphorous, the inhalation of whose fumes caused necrosis (rotting) of the bones of the face — a highly disfiguring condition commonly known as "phossy jaw". The second was the low pay received by employees in the industry despite the large profits made by match manufacturers.

The Darkest England match factory.

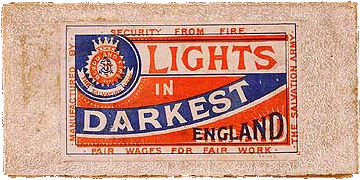

The Darkest England matches were of the "safety" type and used non-toxic red phosphorous. The factory itself was clean, airy, and well-lit. Tea making facilities were provided and the 100 workers were paid 4d. per gross instead of the more usual 2¼d. or 2½d. per gross and were promoted by organisations such as co-operative societies. Booth called the matches "Lights in Darkest England".

Darkest England matches.

By 1901, largely as a result of the pressure public opinion, for which the Army's action can claim much credit, the large match companies had become forced to change their practices and the Darkest England match factory was closed. From 21 December 191, as a result of a parliamentary Act, the use of yellow phosphorous in matches was banned.

The Central Labour Bureau

The Central Labour Bureau was located in the Army's City Colony and Social Headquarters at 272 (later renumbered 20-22) Whitechapel Road. It acted as a clearing house for men seeking work, many of whom were sent to the Army's Elevators and shelters, and the Land Colony at Hadleigh.

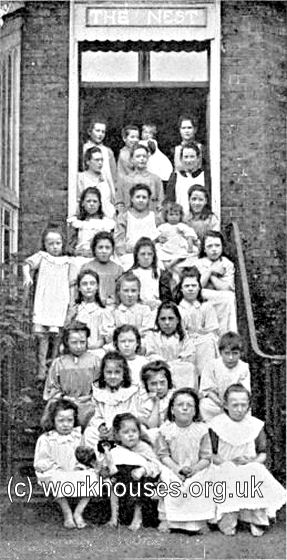

The Nest

In 1901, The Nest, a home for sexually abused girls, was opened at 10 Springfield, in Upper Clapton, London. The home, with a large garden to the rear, accommodated up to 62 girls. Amongst its facilities was an open-air bedroom, adapted from an old greenhouse for those whose lungs were weak.

The Nest, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

To reduce the risk of unhealthy propensities developing in the girls, as a result of their experiences, they were brought up on a vegetarian diet. In a typical week, breakfast on three days comprised porridge with milk and sugar, cocoa, and brown and white bread and butter; on other mornings, figs, prunes, or marmalade were added. A typical midday dinner consisted of lentil savoury, baked potatoes, brown gravy and bread, and boiled rice with milk and sugar. For tea, bananas, apples, oranges, nuts, jam, brown and white bread and butter were served, with tea as a beverage served only on Sundays. Children in the home were educated by a certificated governess.

The Nest, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Bow Road Boys' Home

In the early 1900s, the Army took over Sturge House, 32-36 Bow Road, which was formerly a Dr Barnardo's children's home. The home accommodated around fifty boys or "lads" aged fourteen to eighteen. The boys arrived by a variety of routes, some via Army Shelters, some applying when becoming unemployed, others coming from broken homes. They stayed at the home for a while, were taught and fed, and their characters re-established, before being returned to the outside world. Some who obtained work in London stayed on at the home, paying 5s. per week for their board and lodging. Some were sent off to South Wales to work in the collieries.

Inebriates' Homes

The Army ran several homed for "inebriates" — a term which covered alcoholics and also those addicted to drugs such as laudanum.

Hillsborough House was located on Rookwood Road, Stamford Hill, could accommodate up to 30 female patients who were expected to contribute 10s. a week towards the cost of their maintenance which was around 12/6d. In reality, many paid rather less than this, while a good many gave nothing at all.

Most women stayed in the Home for twelve months, with up to three years subsequent supervision. After this period of care, the home claimed a 50% success rate with its patients. This success was partly attributed to the religious and personal resources of the staff and partly to the effects of an enforced vegetarian diet which was held to induce a distaste for spirituous liquors. Breakfast, served at 7.30, consisted of tea, bread and butter, porridge a milk, or stewed fruit. A typical dinner, at 1 p.m., included macaroni cheese, greens, potatoes, fruit pudding or plain boiled pudding with figs. On one day a week, baked or boiled fish was served with pease pudding, and on another, onions in batter with gravy. Tea, served at 6 p.m., might consisted of cheese sandwiches with salad, or savoury rolls with bread and butter and fruit.

After leaving, married women returned to their husbands, while the unmarried were sent out to positions as governesses, nurses or servants if the Home felt able to provide a good reference. Patients were tracked for several years after discharge to monitor their progress.

Springfield Lodge, at 1 Grove Hill Road, Denmark Hill, provided a similar regime, but catered "the better class" of women patients. It accommodated up to 30 women who were charged between 10s. and a guinea per week, although, as at Hillsborough House, this was reduced according to a patient's ability to pay.

The Army's "Voluntary Retreat for Male Inebriates" opened in October 1901 at Victoria House near Thundersley in Essex.

Ivy House Maternity Hospital

Ivy House, at 271 Mare Street, Hackney, was a 25-bed maternity hospital for unmarried mothers, most of whom were between fifteen and twenty years old. The hospital catered for women both from London and elsewhere. In 1909, 286 babies were born at the hospital, of which 30 died, with premature cases said to be the main cause of mortality.

As well as providing immediate medical care, the Army found work in service for many young women, so that they could support their child. Where possible, they were placed in households where only one servant was kept, so that they would be spared embarrassment from the others finding out their "secret". The Army also made efforts to locate the children's fathers, with the aim of obtaining financial support, either voluntarily or through a bastardy order.

Ivy House also acted as a training school for midwives, some of whom continued to work for the Army either in its Hospital Department or in its Slum Department.

Slum Sisters

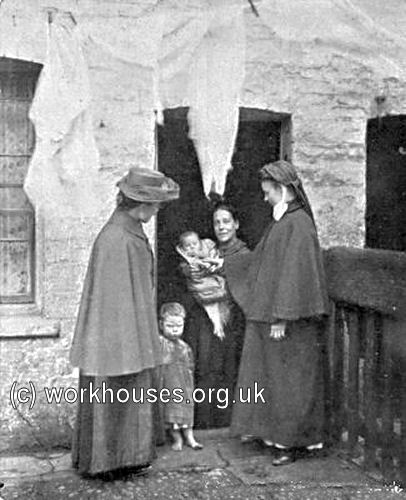

To minister to those whose homes were in what were classed as slums, the Army appointed a number of predominantly female officers who became known as "Slum Sisters". The Slum Sisters (and Nurses and Midwives) visited poor families, the sick, and public houses, and also attended births. By 1910 there were around sixty such staff in London and a similar number in the rest of Britain.

Slum Sisters, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Slums in areas such as the East End typically consisted of old houses divided up so that a single room measuring nine feet square might be occupied by a father and mother and eight or nine children. The demand for such accommodation from country dwellers flocking to the city made it a highly profitable business, with the rent for a containing a family being 5s. unfurnished, or 7s.6d furnished. In the latter case, the furniture might consist of a rickety old bed, two broken-down chairs and a shaky table, worth no more in total than the 2s.6d. weekly charge made for their rent. (At this time, in a country village, the rent for a whole cottage would often be less than 2s.6d. per week.)

In many slum areas, it was not uncommon for money to be earned by "sweating", i.e. long hours of poorly paid home-working, such as making matchboxes or artificial flowers. In a 14-hour day, an expert flower maker could assemble a 18 dozen blooms for which they received 1s.6d (less the cost of glue, scissors etc.) Some Slum Sisters taught themselves this skill so that they might talk to such workers without disrupting their work.

East End children's first sight of a real Christmas, c.1909.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In January 1909, old-age pensions were introduced for the over-seventies. However, anyone in receipt of poor relief, or who had been so since January 1908, was disqualified from a pension. Slum Sisters took a special interest in making sure that those aged sixty-nine were helped to avoid this trap by contributing to their maintenance and ensuring that they did not need to apply for poor relief.

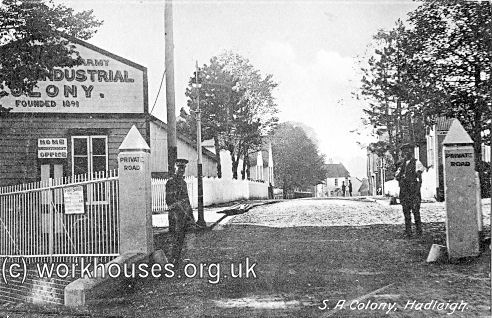

Hadleigh Farm Colony

William Booth's plan for a "Farm Colony" was realised at Hadleigh in Essex where a 3,200-acre estate was acquired in 1891. The land was out of cultivation and much work was needed. By the end of the year, a number of temporary buildings had been erected, including a dining-room, kitchen, five dormitories, bathroom, offices, and a reading room. A 16-bed hospital was opened in October, and large citadel or meeting hall was also built on the site.

Hadleigh Colony site, Newcastle upon Tyne, c.1920.

Around 400 men passed through the Colony each year, with around 230 there at any one time. Men arrived at Hadleigh most often as a referral from the Army's Central Labour Bureau, or after working for a spell in one of the Elevators. Workers received their board and lodging plus a cash "grant" of between 6d. and 5s. per week depending on their ability.

Hadleigh Colony entrance, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hadleigh Colony 'Castle Avenue', c.1910.

Hadleigh Colonists at work, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Colonists produced a variety of field crops, such as wheat, cabbages, and onions, and grew tomatoes in glass-houses. Hadleigh was also noted for its poultry. Nonetheless, like the Hanbury Street workshop, the Colony regularly ran at a loss, a situation which the Army attributed to the poor performance of its labour-force, 92% of whom had a history of drink problems.

Hadleigh Colonists returning home after work, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hadleigh Colony Dormitories from the north, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

As well as providing accommodation and productive employment, Booth's intention was that their time there would equip many of the men for living in his project Oversea Colony. Many men who worked at the Hadleigh Colony did indeed subsequently emigrate to Canada.

Boxted Small-holdings Settlement

In 1906, following a £100,000 donation from a Mr Herring, the Army acquired Priory Farm plus 400 acres of land, at Boxted near Colchester in Essex. The land was divided into 67 small-holdings, ranging in size from 4½ to 7 acres, which were leased to tenants many of whom came from the East End of London. Pairs of cottages were also erected on the site, each cottage comprising three bedrooms, a large living room, a parlour, and a scullery containing a sink and bath. There was also a toolhouse, pigsty, and moveable fowl-house on wheels. New tenants were also provided with seed, manure, and fruit trees and bushes. Produce from the site was marketed through the Boxted Smallholding Co-operative Society.

The scheme never really became established and by 1912, half the cottages were unoccupied. In 1916, the estate was bought by Essex County Council and by 1922 ex-servicemen had been placed there, but they too found it difficult to make a living. The small-holdings were later leased to farm workers and in the 1950s many were sold to their then tenants.

The Over-Sea Colony

The Over-Sea Colony was the one part of Booth's scheme never to be achieved, at least not in the form in which it was originally conceived. He had outlined a three-stage strategy for creating the Colony:

- Preparing the Colony for the people: this would involve identifying and securing suitable tract of land, creating an initial settlement of competent men to erect building, establishing the first crops, and storing enough food for the future. Further colonists would then be despatched to consolidate and extend the initial work into further areas, until the Colony could absorb a continuous stream of emigrants. Finally, a strong and effective government and legal system would be created along the lines of that in England.

- Preparation of the people for the Colony: this, wrote Booth, would involve their "education in honesty, truth, and industry, without which we could not indulge in any hope of their succeeding. While men and women would be received into the City Colony without character, none would be sent over the sea who had not been proved worthy of this trust."

- Arrangements for the transport of the people when prepared: the cost of transport would, Booth estimated, be no more than £8 per head, which Colonists could raise from friends, or their earnings at the City and Farm Colonies. Once settled in the new life, Colonists could help pay the passage of future arrivals. At the full fruition of the scheme he predicted that "the transfer of the entire surplus population of this country is not only possible, but would, we think, in process of time, be effected with enormous advantage to the people themselves, to this country, and the country of their adoption.

Despite initial optimism, with offers of land being received from no less than 38 countries or states, the scheme got nowhere. Strong public opposition arose in some of the most promising locations, such as Australia and New Zealand, from fears the local labour market would be swamped. The British public also appeared to lack enthusiasm for the scheme and failed to donate the necessary funds to finance it.

However, the Army had more success with its efforts to promote the emigration of the poor by more traditional means. As early as 1882, it had been involved in finding women emigrants for Australia. In 1891, passages for 95 emigrants were arranged, with employment also having been organised in advance for many of them. In 1894, the Army set up an Emigration Board, presided over by the General's son, Bramwell Booth.

From 1901, small batches of men from the Hadleigh Farm Colony had, after training, been despatched to Canada. In 1903, a much larger programme of emigration was initiated, with almost 200 embarking in a single week in April 1904. An Emigration Advice Bureau was then set up, its rapid growth soon resulting in its moving into its own building at 27 Queen Victoria Street. In 1905, the Army chartered its own ship, the S.S. Vancouver, which sailed on 26th April to Canada with a 1,000 emigrants aboard. Many more such sailings followed on vessels that include S.S. Kensington, S.S. Southwark, and S.S. Ionian. The Bureau's continuing growth led, in 1907, to its move to even larger premises at 122 Queen Victoria Street where it was renamed the Emigration Department.

Families leaving for Canada escorted by a band, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the end of the First World War, to help the plight of widows and their children, the Army arranged for a total of 1,769 women and 1,019 children to emigrate to new lives in Canada, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. In the late 1920s, the Army arranged the passage of several consignments of emigrants to Australia on the Vedic. By 1938, the overall total of men, women and children settled overseas by the Emigration Department was almost 250,000.

Bibliography

- Booth, William (1890) In Darkest England, and the Way Out (London: International Headquarters of the Salvation Army)

- Haggard, H Rider (1910) Regeneration (London: Longman's, Green & Co.)

- Sandall, Robert (1955) The History of the Salvation Army (London: Nelson)

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.