Swineford (Swinford), Co. Mayo

Swineford Poor Law Union was formed 11th April 1840 and covered an area of 207 square miles. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 21 in number, representing its 12 electoral divisions as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Co. Mayo:

Aughamore (2), Bohola, Kilbeagh (3), Killasser (2), Killeaden (2), Kilmoree (2), Knock, Meelick, Swineford (2), Toomore.

Co. Sligo:

Achonry (2).

Co. Mayo and Co. Sligo:

Kilmacteigue (2).

The Board also included 7 ex officio Guardians, making a total of 28. The Guardians met each week at 11am on Tuesday.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 65,965 with divisions ranging in size from Knock (population 3,036) to Kilbeagh (8,639).

The new workhouse, built in 1840-42, occupied a 6-acre site on the southern side of Barrack Street to the east of the town. It was designed to hold 700 inmates and its construction cost £7,100 plus £1,300 for fixtures and fittings etc. It was declared fit for the admission of paupers on 30th November 1842 but did not admit its first inmates until 14th April 1846.

The building was constructed to one of George Wilkinson's standard designs with an entrance block at the north containing a board-room, offices and a dispensary. Behind this stood the large main block, with women's accommodation to one side and men's to the other. At the rear, connected via a central spine, was a infirmary block. To the south of the main workhouse buildings stood a small fever hospital built during the famine in 1847. On the north side of Barrack Street stood the workhouse burial ground. The site layout can be seen on an early Ordnance Survey map:

Swineford workhouse site.

Swineford entrance from the north, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Swineford entrance block from the north-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Swineford date stone, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Swineford workhouse entrance block from the west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The delay in the workhouse admitting its first inmates was due in part to the antipathy of local people to its presence and great difficulties in collecting the local poor rate needed to finance the running of the workhouse. However, with the onset of the Great Famine in 1846, this resistance gave way and the workhouse was full within a few months. James Tuke, a Quaker, visited some workhouses in the west of Ireland that were suffering the growing strains placed on them by the famine. He recorded that at Swineford workhouse on 10th November:

The following year, sometimes referred to as "Black '47", diseases such as typhus and dysentery took hold in the workhouse, and six hundred bodies were buried in a mass grave.

British Parliamentary Papers for 1848 include a letter written by a local minister which begins:

January 8, 1848.

I beg to state for the information of the Poor Law Commissioners, that the poor starving people of this electoral Shrule division are almost neglected by the Vice-Guardians of this Union. About three or four-hundred of the most destitute families of this division have crawled to Ballinrobe (a distance of 10 or 12 miles), every Friday for the last month, seeking admission to the workhouse or out-door relief. This I can certify, for I have accompanied the poor creatures thither in order to represent their wants to the Guardians; and yet, though they remained each day until night, standing in wet and cold at the workhouse door, craving for admission into the house, they have got no relief and I do now most solemnly assure you that, but for a few shillings which I used to distribute to buy bread to enable their poor families to return home very many of them would have died by the road-side whilst returning from Ballinrobe. Six poor creatures who have been dragged to Ballinrobe in this manner, have died in this electoral division this week, and I am greatly afraid that treble that number will meet the same awful death before this day week.

In 1879-81, Ireland suffered another agricultural crisis, with bad weather and poor harvests leading to food shortages and unemployment, with the west of Ireland being particularly afflicted. The British government instigated an ineffectual scheme to fund public works schemes via loans to land-owners. However, the main source of relief during the winter of 1879-80 came from voluntary and charitable organisations, with many Boards of Guardians restricting out-relief either as a matter of policy or because of lack of funds to pay for it. In the summer of 1880, the Local Government Board dissolved the Swineford Board of Guardians (and also those of the nearby Newport and Belmullet unions) for failing to collect sufficient rates to provide relief. The LGB then installed its own vice-guardians to try and restore the union to financial order.

At the 1901 census, the population of the Union was 44,162.

Today, the entrance block to the workhouse survives and is used for geriatric care.

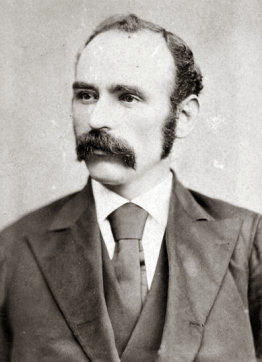

Michael Davitt

One of the Swineford workhouse's most notable inmates was Michael Davitt, a native of Straide Co. Mayo. In 1850, at the age of four-and-a half, Davitt entered the workhouse for a short time with his destitute mother due to arrears in their rent. In the 1880s, Davitt was a founder and also chairman of the Land League, a prominent agrarian protest organization in Ireland. He later entered Parliament, and was an eminent socialist campaigner, writer, and lecturer, his views undoubtedly owing much to his childhood penury, including his time as an inmate at Swinford.

Michael Davitt

Staff

In 1905, workhouse staff were as follows:

- Master - Pat Flynn

- Matron, Nurses and Infirmarian - Sisters of Mercy

- Chaplain - Very Rev. Michael Staunton

- Medical Officer - Francis Richard O'Grady

- Schoolmistresses - Sisters of Mercy

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Local History Department, Castlebar Central Library, Castlebar, Co Mayo.

Bibliography

- Crossman, V (2006) Politics, Pauperism and Power in Late Nineteenth-century Ireland

- Gray, P (2009) The Making of the Irish Poor Law, 1815-43

- Hamrock, I (1998) The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850.

- O'Connor, J (1995) The Workhouses of Ireland

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.