Stockport, Cheshire

Up to 1834

The existence of a parish workhouse in Stockport is mentioned in the SPCK's "An Account of Several Work-houses..." in a report dated November 1731:

A parliamentary report of 1777 listed parish workhouses at Stockport (for up to 60 inmates) and Marple (9 inmates).

After 1834

The Stockport Poor Law Union formally came into being on 3rd February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 21 in number, representing its 16 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

County of Chester:

Bramhall, Bredbury, Brinnington, Cheadle Bulkley, Cheadle Mosley, Hyde (2), Marple, Norbury, Offerton, Romilly, Stockport (4), Stockport Etchells, Torkington, Werneth.

County of Lancaster:

Heaton Norris (2), Reddish.

Later additions: Bosden (1877), Compstall (1897), Handforth (1877), Hazel Grove and Bramhall (1900).

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 68,906 — ranging from Torkington (population 284) to Stockport (25,469).

Stockport, like a number of other northern manufacturing towns, was the scene of some resistance to the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. On 23 January 1837, a meeting of local ratepayers was held in the town to nominate people for the office of Guardian. The meeting's chairman, Mr Rawlinson, expressed opposition to many clauses on the 1834 Act but asked speakers to confine themselves to the business in hand. However, several present criticized the Act as 'unchristian and unconstitutional' and urged that no Guardians be nominated. The meeting eventually broke up in disarray.

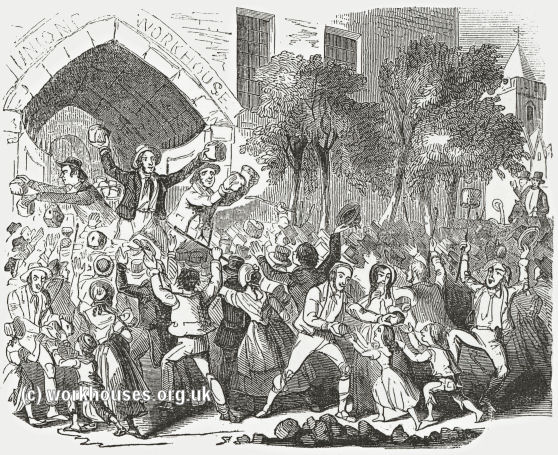

Initially, the new Stockport Union continued to use an existing parish workhouse, but a new building was erected in 1841-2. Soon after its opening there was a widespread manufacturing slump which led to demonstrations and riots in many northern areas. In August 1842, Stockport's workhouse was the subject of an attack by a mob of unemployed workers as described in a contemporary news report.

Stockport workhouse under attack, 1842.

The new workhouse was designed by Henry Bowman who was also responsible for the Congleton workhouse. The new workhouse was built at Shaw Heath and was intended to accommodate up to 690 inmates. Its location and layout are shown on the 1851 map below.

Stockport workhouse site, 1851.

The workhouse comprised a two-storey entrance block facing the main road at the south-west. Assorted other buildings were subsequently added at each side.

Stockport general view from the south, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham

The main accommodation building stood to the rear. It was substantial red-brick building, largely four storeys high. Males were accommodated at the north side and females at the south. Children's quarters and school rooms were located in cross wings at each end of the main block, with the area to the front containing enclosed boys' and girls' exercise yards. To the rear, the men's and women's sides were divided by the kitchens, dining-hall and bakery. A wash-house and drying ground for laundering linen and clothes were located at the women's side, while a smithy and pig-sties were placed at the men's side.

Stockport main building from the south, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham

Stockport rear of main building from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

Stockport rear of main building from the east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham

Stockport rear of main building from the east, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham

The floors of the main block were connected by a concrete staircase. This one has overhead rails fitted — presumably to prevent inmates falling or jumping down the central well.

Stockport internal staircase with protective overhead rails.

© Peter Higginbotham

Stockport top floor of central hub.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse had clocks on three sides — the original clock mechanisms still operate.

Stockport clock mechanism.

© Peter Higginbotham

The upper dormitory floors of the boys' and girls wings were connected by an internal staircase.

Stockport third floor of girls' wing.

© Peter Higginbotham

Communal washing facilities in the workhouse appear to have been very modest. This sink on one of the landings served a large part of the women's side.

Stockport old workhouse sink.

© Peter Higginbotham

The workhouse walls were emulsioned many times. In earlier times a distinctive "hospital blue" shade was used — traces of which could still be found in recent times.

Stockport Hospital Blue emulsion.

© Peter Higginbotham

A separate hospital block was later erected at the north of the site.

Stockport hospital block from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. On their visit to Stockport, the commission found that due to a trade depression, inmates in the workhouse were "packed like sardines in a tin." The management of the hospital appeared to be "completely without plan or method" and the female wards were "comfortless and barnlike". Many wards were so crowded as to present a serious danger in the case of fire. Former school rooms had been pressed into service as wards for the old and infirm. There were no day rooms and the men smoked in the wards, often being confined there for days on end during the winter. The workhouse staff, though, were praised for their energy and for doing their utmost for the patients under most discouraging circumstances. The commission's report recommended that the only remedy was the building of a new infirmary — a course of action also urged by the Local Government Board, but to which there was local opposition. Further details are available in the full report.

In 1905, a new office and board-room block was erected at the west of the workhouse site at the corner of Flint Street.

Stockport Union offices from the south, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham

The later layout of the site is shown on the 1910 map below.

Stockport workhouse site, 1910.

The workhouse later became Shaw Heath Hospital, then from 1954 was known as St Thomas' Hospital. The hospital finally closed in 2004 and the site was acquired by Stockport College as part of their campus expansion. The main workhouse building and some other blocks were planned to be retained and refurbished although have since remained disused.

Interestingly, the Rector of St Thomas' church is still the official chaplain to the workhouse. To this day, he receives a small annual cheque for this post which is then deducted from his salary as rector.

Stepping Hill Infirmary

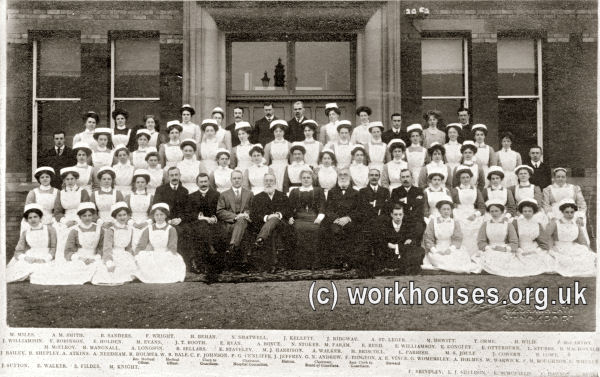

By 1894, as noted above, the Stockport Guardians came under pressure from the Local Government Board to improve their medical facilities by establishing a new infirmary. Building work on this establishment finally got underway in 1901 on a site at Stepping Hill, to the south-east of Stockport. It was formally opened in December 1905 by Mr G.N, Andrew, Chairman of the Stockport Guardians.

Stepping Hill Infirmary staff and union officers, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham

The buildings, designed by WH Ward, could accommodate 340 patients, plus 36 nurses, and 24 other staff. The layout was a typical pavilion-plan design with a central administration block flanked by pairs of three-storey nightingale ward blocks all linked together on each floor by an open-air walkway. Other blocks housed maternity and lying-in wards, nurses' home, laundry, mortuary. A porter's lodge stood at the entrance to the site on Poplar Grove.

Stepping Hill site, 1922.

Stepping Hill aerial view from the south-west, 1927.

© Peter Higginbotham

The three-storey administration block contained quarters for the matron, medical officer and steward, a committee room, dispensary, kitchens, stores, and boiler room. A lift adjacent to the kitchen allowed food to be transferred to the corridor at each level for distribution to the upper floors of each ward block.

Stepping Hill administration block from the south-east, c.1913.

© Peter Higginbotham

Each floor of the ward pavilions was 24 feet wide by 72 feet long and contained 24 beds — 12 along each side, with a window placed in between each pair of beds. The nurses' duty room lay at the end of the ward nearest the linking corridor, while the farther end housed baths, toilets, escape stairs, and a verandah.

Stepping Hill infirmary from the south-east, c.1913.

© Peter Higginbotham

Some of the original infirmary buildings survive as part of the much enlarged Stepping Hill Hospital.

Children's Homes

In the early 1900s, following the trend to house pauper children away from the workhouse, the Stockport Union established a number of 'scattered homes' in and around the town. These included properties at: 2 Hall Street; 1 Mount Vernon, Turncroft Lane; 20-26 St Thomas's Place; Brook House, 41 Bank Lane; and The Cottage, Heaton Road, Heaton Norris. Each housed a number of children together with a house mother.

The scattered home at 2 Hall Street, 2013.

© Peter Higginbotham

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Stockport Archives, Central Library, Wellington Road South, Stockport SK1 3RS. Most records were destroyed during World War 2. Surviving records include: Workhouse Births and Deaths (1850-1904, indexed); Lists of inmates and removals (1841-3); Lists of paupers (1837-43, 1853-73 with gaps; Register of deaths and diseases (1874-95); etc.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Workhouse Encyclopedia (2014, The History Press)

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.