The Workhouse in Scotland

(Note — workhouses in Scotland were more usually termed 'poorhouses'.)

Prior to 1845

The earliest Acts of the Scottish parliament relating to the relief of the poor date from 1424 when a distinction was made between able-bodied beggars and those who were unable to earn their own living. The latter could be given permission to beg by the authorities the form of a badge or token to carry with them. Another Act in the following year made able-bodied beggars liable to be arrested and given forty days to find work else be put in prison. Over the next century and a half a series of further Acts followed aimed at the 'staunching' of beggars, none of which proved effectual.

Provision for the deserving poor was formalised in an Act of 1535 (27 Henry VIII c.25) which made each parish liable for the support of its own aged and infirm poor and collections to be made for that purpose.

In 1579, an act of the Scottish Parliament For Punischment of Strang and Idle Beggars, and Reliefe of the Pure and Impotent (James VI, c.24, October 26, No.12) laid the basis of the system of poor relief in Scotland that was to continue for the next three centuries. Under the Act, 'strong and idle' beggars were to be branded on the ear, with the death penalty for repeat offenders. Each parish was to make a list of its own poor (those who had been born there or who had lived there for seven years or more), "that the aged, impotent, and pure people, suld have ludgeing and abiding places". Heritors (land-owners) could take the children of beggars into unpaid service until they were eighteen, in the case of girls, or twenty-four, for boys.

A further act in 1597 (James VI, c.272, November 3rd, No.39) restated the 1579 Act, but added that 'strong beggars and their bairns' — effectively, all the able-bodied poor — should be employed in 'common work'. Implicitly acknowledging that previous legislation had been ineffectively implemented by the civil authorities, the Act also shifted the responsibility for carrying out poor relief directives to the Kirk Sessions — the church authorities in each parish.

Money for poor relief provision was raised in a number of ways. In Aberdeen, for example, they included:

- Church door collections

- Donations to the church by private individuals

- Hiring out a hearse

- Interest on monies lent

- Income from rents

- Fees from baptisms, marriages, and burials

An act of 1672 ordered magistrates to erect "correction houses" or workhouses in which beggars could be detained and made to work. One of the earliest recorded workhouses, "the workhouse called Paul's work", is known to have operated in Edinburgh from at least 1720.

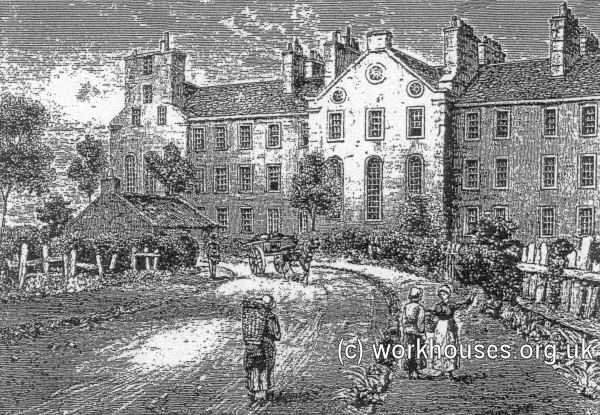

The Edinburgh Charity Workhouse in Port Bristo opened in 1743 and was financed by voluntary subscriptions. Funds for its operation were raised by a variety of means such as a tax on the valued rents of the city, collections at church doors, charitable donations and other contributions including an annual benefit play at one of the city's theatres. It was a substantial building that, in 1777-8, could accommodate 484 adults and 180 children.

Edinburgh Charity Workhouse, 1820.

In 1761, Edinburgh's West Kirk parish opened the Canongate Charity workhouse at the east side of Tollbooth Wynd. It was financed by church-door collections and voluntary contributions, and managed by annually chosen members of various public societies such as the incorporated trades.

In Glasgow, a workhouse known as the Town's Hospital, was founded in 1731. The Hospital was managed by the Lord Provost and a group of 48 directors: 12 elected by the town council, 12 by the General Session (representing the church in each parish), 12 by the Merchants' House (the merchants' guild), and 12 by the Incorporated Trades (the producers' guild).

The Act of Union of 1707 had allowed Scotland to retain its own judicial system. Because of this, the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 did not extend to Scotland. However, by the 1840s, it became apparent that reform was necessary. The demand for relief exceeded supply and it was administered very irregularly. A further factor, in 1843, was the Disruption where the established Church of Scotland suffered a split with forty percent of its clergy leaving to form the Free Church. The existing system of administration via the Church of Scotland's Kirk Sessions was no longer effective after half its members had departed. In January 1843, a Commission of Enquiry was set up to inquire into the system of poor relief in Scotland and suggest improvements.

The 1845 Scottish Poor Law Act

The Commission's report, delivered on 2nd of May 1844, noted that poor relief in Scotland was generally confined to the old, infirm, disabled, mentally ill and so on, and that relief to the able-bodied was rare. They therefore proposed to broadly keep relief organized at the parish level. Their main recommendations were:

- A central Board of Supervision would regulate the operation of the new system. The Board's membership comprised the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, the Lord Provost of Glasgow, The Solicitor General of Scotland, the Sheriffs Depute of the counties of Perth, Renfrew, Ross and Cromarty, and three other persons appointed by the Crown.

- Each of the country's 880 parishes was to have its own Parochial Board of managers, locally appointed each year.

- The parochial board would decide whether to raise poor relief funds voluntarily, or to impose a poor rate "according to any established usage" — generally based on assessment of property ownership.

- Poor relief could be given in the form of cash or in kind, or a poorhouse could be set up to shelter the sick or destitute, but not the able-bodied.

- Parishes, particularly in urban areas, could be united for settlement and poor-relief purposes, including the establishment of joint poorhouses.

- Poorhouses could be set up only by parishes, or Combinations of parishes, whose population exceeded five thousand people.

- An Inspector of the Poor in each parish would examine all applications for relief.

These proposals were put into effect on 4th August 1845 in an Act for The Amendment and better Administration of the Laws Relating to the relief of the Poor in Scotland (8 & 9 Vic. c.83). You can read the full text of the 1845 Act.

The Scottish Act was therefore significantly different from the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act which applied in England and Wales and subsequently extended to Ireland. In Scotland, the able-bodied were exempt from receiving relief. Relief was not to be confined to the workhouse/poorhouse, and the operation of poorhouses was voluntary.

After the 1845 Act, there was a steady movement away from voluntary fund raising towards the assessment system. In 1845, only 230 of Scotland's 880 parishes were using the assessment system, but by 1853 this had risen to 680.

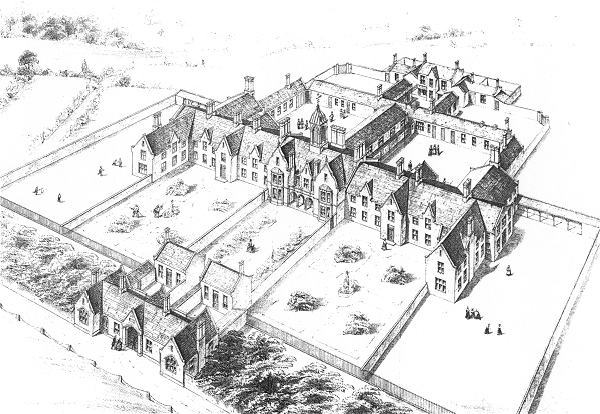

Although the 1845 Act allowed parishes to operate poorhouses, it did not require them to do so as was the case in England and Wales after 1834, and in Ireland after 1838. Adjacent Scottish parishes could also join together to form "Combinations" and operate Combination poorhouses. Approval for such arrangements had to be given by the Board of Supervision. In 1847, the Board published model plans for rural and town poorhouses.

Model Poorhouse Plan for Town Parishes, 1847

Aberdeen former poorhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1848, the Board reported that it had approved plans for eight new poorhouses, together with the enlargement of poorhouses in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Around seventy poorhouses were eventually in operation, about three-quarters of which were run by Combinations. However, the majority of Scotland's paupers continued to receive out-relief, with many poorhouses rarely more than half full. By the 1890s, there was accommodation over 15,000 inmates in Scotland's poorhouses, though the average number of inmates was usually between 8,000 and 9,000.

Poorhouse Operation

The operation of poorhouses in Scotland was in many respects based on that adopted for workhouses in England and Wales. Inmates were classified as follows:

- Males above the age of 15 years

- Boys above the age of 2 years, and under 15 years

- Females above the age of 15 years

- Girls above the age of 2 years, and under 15 years

- Children under 2 years of age

Segregation of inmates, particularly of males and females, was also enforced.

For paupers entering the poorhouse, life was strictly regulated. There was a prescribed daily routine and work was expected to be performed by inmates according to their capabilities. Inmates were required to wear the poorhouse uniform. An inmate's own clothes were "purified" by steaming it for three hours and then placing it in store until the inmate left the poorhouse.

The inmates' diet was also prescribed. For working adults, this comprised:

| Breakfast | Meal, four ounces; and broth, three-fourths pint imperial. |

| Dinner | Bread, eight ounces; broth, one-and-half pint imperial; and boiled meat, four ounces. |

| Supper | Meal, four ounces; and broth, three-fourths pint imperial |

Inmates were bathed once a week, under supervision, in water between 88 and 98 degrees Fahrenheit. Children under fifteen had their hair regularly cut to keep the length at two inches for boys and three inches for girls.

Although the Scottish poorhouse system was not intended to accommodate able-bodied, poorhouses such as Glasgow later set up small "test wards" for inmates who judged to be "bad characters" or who were suspected to be able to support themselves outside the poorhouse. Test ward inmates were kept separate from other inmates and given a stricter regime. Men could be required to do stone-breaking or wood-cuuting, while women were given knitting to do.

Edinburgh

In 1869, Edinburgh's old Charity workhouse was replaced by the Craiglockhart Poorhouse which had accommodation of up to 1569 inmates. It was intended to provide both a 'comfortable home for the aged and poor' and also a reformatory for the 'dissipated, the improvident, and the vicious'. The male wing had divisions for 'old men of good character', 'dissolute men', 'doubtful old men', and 'boys', with similar divisions in the women's quarters.

Edinburgh Craiglockart Poorhouse from the south-west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Edinburgh's St Cuthbert's parish opened a new poorhouse and hospital in 1868. The poorhouse had separate sections for 'Very Decent', 'Decent', 'Bastardy', and 'Depraved'.

St Cuthbert's main block entrance from the south, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1873, St Cuthbert's merged with Canongate, forming St Cuthbert's Combination.

Glasgow

After 1845, poor law provision in Glasgow was divided between four parishes: City, Barony, Govan and Gorbals. Gorbals never set up a poorhouse and was absorbed by Govan in 1873.

The City Poorhouse on Parliamentary Road was originally erected in 1809 as a lunatic asylum. With 1,500 beds, it was one of the largest institutions in Britain. Poor conditions and overcrowding in the City Poorhouse were a recurring subject of concern. It closed in 1905 following a merger with Barony parish.

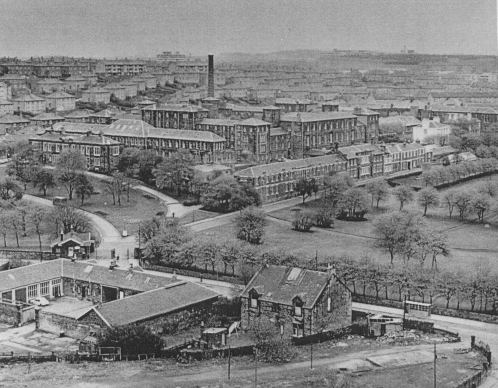

The Barony Parish Poorhouse at Barnhill opened in 1853 and was described in 1882 as "a very capacious asylum for the children of poverty and well adapted by its cleanliness, ventilation and position to mitigate the ills of their condition." With the merger with the City parish, it was enlarged and became Scotland's largest poorhouse.

Barnhill poorhouse from the south-west.

© Heatherbank Museum of Social Work.

The Highlands and Islands

Most of the earlier poorhouses were erected in Scotland's more highly populated southern lowlands. The first poorhouse erected in the highlands was in 1850 in Tain, which served a combination of nine parishes in Easter Ross. Under pressure from the Board of Supervision, poorhouses were eventually erected in most parts of the highlands and islands. However, they often were larger than demand warranted and not proved costly to build and to run, and their never approached anywhere near their capacity. The situation was aggravated in the 1880s by such factors as the failure of potato and grain crops, difficulties in the fishing industry, and disputes over land rights, all of which contributed to some Combinations going into debt. By the early twentieth century, proposals were being made for the conversion of poorhouses in the highlands and islands to other uses, such as the accommodation of the mentally ill. This first came into effect at the Long Island in 1907 when the poorhouse at Lochmaddy was licensed for the reception of 28 "harmless lunatics" in addition to the ordinary poor. The parishes of the Long Island Combination were thus saved the expense of sending such cases from the Hebrides to the asylum at Inverness. In 1911, a similar scheme came into operation in the Lewis Combination poorhouse at Stornoway.

Orkney former poorhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham

The Later Years

In 1894, the Board of Supervision was replaced by a more powerful Local Government Board which was directly responsible to Parliament. The parochial boards were replaced by parish councils which held office for three years at a time. An increasing emphasis was placed on the provision of improved hospital facilities. In Glasgow, for example, following the creation of a single poor law authority in 1904, three new establishments were built: Stobhill Hospital (for the infirm and chronic sick poor, and for children), the Eastern General Hospital (an acute hospital with psychiatric assessment wards), and the Western General Hospital (for acute medical and surgical cases).

As in the rest of Britain, a number of poorhouse buildings were used during the First World War for military accommodation or for the treatment of military casualties. After the passing of the Local Government Act of 1929, many poorhouses evolved into Public Assistance Institutions offering care for the elderly, infirm, chronic sick, and unmarried mothers-to-be. In 1946, as part of preparations for the setting up of the National Health Service, many former poorhouse buildings were evaluated. Some were refurbished or upgraded to take on a role under the NHS. Others were condemned and sold off or demolished.

Almshouses

After 1845, the setting up of what were sometimes referred to as 'statutory' poorhouses — those whose operation was supervised by the Board of Supervision — was limited to larger parishes parishes or parish combinations. However, more than a hundred Scottish parishes operated sestablishments generally referred to as 'almshouses' or 'parish homes'. Although a few large almshouses such as Brechin and Peterhead were comparable to poorhouses, most were quite small establishments. Rather than the dormitories that characterised poorhouses, almshouse accommodation was more likely to be arranged as small apartments or cottages. The inmates ("persons of good character") could live with as much freedom as in their own homes, often with their own furniture, and buying and cooking their own food. A lsit of the locations of parish almshouses are given on a separate page.

Bibliography

- Poor Relief in Scotland by the Scottish Record Office (1995).

- Poor Relief in Scotland by Alexander Cormack (1923, Wyllie & Son, Aberdeen).

- Public Administration in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland by JP Day (1918, University of London Press).

- Poorhouse Management by GA Mackay (1908, William Green and Sons, Edinburgh).

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.