Clerkenwell (Parishes of St James and St John), Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

A joint workhouse for the parishes of St James and St John was erected in Clerkenwell in 1727 under the provisions of Knatchbull's Act of 1723. It was situated on the west side of Farringdon Road (formerly Coppice Row).

The 1732 edition of An Account of Several Workhouses... reported of Clerkenwell that:

In 1729, an Infirmary was built at one End of the Work-house, upon considerable Encouragement given by the Executors of Henry Hoare, Esq; out of a Legacy of 2000l. left by him towards the Support of Charity-Schools and Workhouses.

In this House, the Institution of Work-houses for Cleanliness and good Order seems to be carried to a Perfection worthy the Imitation of in Other Places: The Tenderness of the Managers of it is so great towards the Persons under their Care, that the Poor enjoy every Thing they can reasonably desire, while they are content to be restrained from strolling abroad, in Hunger and Nakedness; and by the Prudence of their Overseers, are made mutually subservient to the Comfort of each other.

In 1775, the parish promoted a parlimentary Local Act "for building a Workhouse, and for the better Relief and Employment of the Poor, within the Parish of Saint James, Clerkenwell" otherwise known as the Clerkenwell Poor Relief Act. The Act allowed for poor relief in the parish to be administered by a board of up to 63 Guardians comprising 42 for the district of Saint James, and 21 for the district of Saint John. The Guardians took the business of manageing poor relief out of the hands of the Vestry, although relief was still funded by the poor rate collected by the parish overseers.

The 1775 Act gave the Guardians the power to erect a new workhouse or to enlarge the existing one. The latter course appears to have eventually been taken in 1790 when the old workhouse at west side of Coppice Row (now 143-157 Farringdon Road) was substantially enlarged at a cost of £4,000. The new building comprised three storeys plus a basement, with apartments for the Master and a handsome committee-room for the Guardians of the Poor. There was also a large separate block behind. The cost of the reconstruction caused complaint because there was only 40 years remaining on the site's lease at the time.

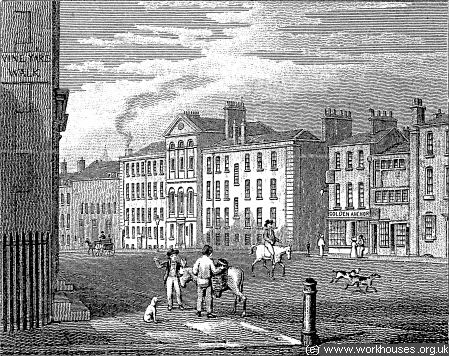

Clerkenwell workhouse from the north, c.1827

Figures for Lady Day 1827 show that the total number of inmates was 500 (211 males, 289 females). The largest proportion of inmates were the over-sixties who numbered 219 (78 males, 141 females). The parish also housed pauper infants (26 in 1826-7) at a separate establishment in Enfield, and lunatics (16) at Bethnal Green. Out-relief was also provided to 125 solitary widows, 435 widows with families, 82 aged and infirm, and 189 illegitimate children.

Clerkenwell workhouse site, 1850s

After 1834

Clerkenwell continued to operate as a local Act parish after 1834, and like a number of other London parishes, fell outside the operation of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

In September 1865, Clerkenwell was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal The Lancet investigating conditions in London workhouses and their infirmaries. The report revealed Clerkenwell as having some of the worst conditions of any workhouse infirmary in London.

The parish of Clerkenwell elect its guardians and manages its workhouse under special local Act of Parliament, and it has certainly abused to the uttermost the opportunities for evading necessary reforms which are created by this position of affairs. The workhouse, in which there exists no trace of a proper separate infirmary, is a tall, gloomy brick building, consisting of two long parallel blocks separated from each other by a flagged court-yard not more than fifteen or twenty feet wide. The front and principal block does enjoy one fair outlook towards a wide street ; but in other respects the whole house is closely environed with buildings only less gloomy and unwholesome looking than itself. The hinder block, especially, wears an aspect of squalid poverty and meanness; and it is very old, dating from 1729. Both blocks are four stories in height. Entering either part of the house, we are at once struck with the frowsiness of the atmosphere which meets us ; and we find the cramped winding staircases, interrupted by all manner of inconvenient landings and doors, which in these old buildings render the stairs a special nuisance, instead of an effective source of ventilation for the building, as they should be. Detailed examination of the sick ward implies detailed inspection of the whole house; for the sick, infirm, insane, and "able-bodied" wards are jumbled side by side, and the whole place presents the dismal appearance of a prison hospital — not such as one meets with in civil life, but the sort of makeshift which might perhaps be seen in a garrison town in war-time, except that in the latter situation one would not be annoyed by the shrieks and laughter of noisy lunatics — one of the special features of the Clerkenwell establishment.

The master is an excellent officer, accustomed all his life to the management of sick people, and with the valuable experience of a model prison (in which he formerly officiated) on matters of sanitary precaution ; and his efforts are well seconded by his wife, the matron. These officers work well with the surgeon, Dr. J. Brown ; and the most zealous endeavours are made by them to remedy defects which are really irremediable. They have one paid nurse under them, who is an experienced and valuable woman ; and with her assistance, as much supervision as possible is given to the incapable paupers who do the real bulk of the nursing. As far as the strictly medical service goes, the sharp supervision of the superior officers seems to prevent the possibility of any such scandalous inattention to the wants of the sick as was noticed at Shoreditch ; but the discovery which we made, that the disgusting practice of washing in the "chambers" was carried on in several of the infirm wards, sufficiently showed the character of the pauper attendants, and prepared us for the very qualified encomium of the master, who informed us that they were, on the whole, a sober, well-conducted set so long as they were never allowed outside the workhouse doors for a moment.

But it is the character of the wards, and their degree of fitness for hospital purposes, that we must chiefly pay attention to. It is necessary first to mention the elements of which the population is made up: in a total number of 560, which represents a crowded state of the house, there would be about 250 sick, and 280 infirm (including about 80 insane). This amount of population exceeds the Poor-law Board's estimate by 60, and the consequence is a reduction of the cubic space per bed, on the average of all the sick wards, to 429 feet, which of itself implies a dangerous state of things. But this imperfect allowance of entire space is aggravated greatly by the low pitch of the wards, the very insufficient number of windows (which are only on one side, except in a few wards), and the absence of any free currents of air circulating through the house. Subsidiary ventilation has been attempted with much perseverance by the surgeon and the master, and a great mitigation is, doubtless, effected of what would be otherwise an intolerable and very fatal nuisance ; but still the atmosphere of the wards is very impure, and if the vigilance of the nurses, as is certain to be the case, at times relaxes, so as to allow the closing of ventilating orifices, a very dangerous foulness of air must ensue. And besides the deficiency of the wards generally in ventilation, there are some which are almost unique, we should fancy, for their badness in this respect. The four tramp wards (two male and two female) afford the following allowances respectively of cubic space — 120 ft., 240 ft., 198 ft., and 184 ft. — to each sleeper : and two of these apartments may dispute the palm successfully, for gloom and stifling closeness, even with the St. Martin's tramp wards. In one there is actually no window at all, but only a bit of perforated zinc over the door, and a solitary ventilator of very doubtful utility. In these nasty places the "casuals" lie upon straw beds, spread upon a sort of wooden gridiron framework, and they must needs huddle so close as to be almost in contact with each other. (N.B. At Clerkenwell the tramps are not washed before being allowed to lie down.) The master is well aware how improper a lodgment these wards afford ; but, with the existing workhouse, it is impossible for him to find better accommodation for so many vagrants as he is obliged to admit.

Not to linger too long over the sanitary abominations of this house, we may mention one which seems to us most scandalous and disgraceful, but which the guardians, one can hardly help thinking, must have been led to establish by a sort of sentimental feeling. They placed the parish dead-house in a snug corner of the yard before-mentioned, and with a ventilation capable of wafting reminiscences of departed parishioners to the inmates of the wards whose windows overlook the mournful edifice.

Perhaps the most painful consequence of the inefficient lodgment which the house affords to its motley population is the impossibility of classification, even where this is most urgently needed. The arrangements for the insane afford a shocking example of this. Such a spectacle as is presented by the two wards in which the more serious male and female insane cases are treated is not often to be seen in these days of enlightened alienist management. The women's ward, in particular, offers an instance of thoughtless cruelty which nothing call excuse the guardians for permitting. Twenty-one patients live entirely in this ward, which affords them an allowance of only 459 cubic feet each ; and the mixture of heterogenous cases which ought never to be mingled is really frightful. There is no seclusion ward for acute maniacs, and accordingly we saw a poor wretch who for five days had been confined to her bed by means of a strait-waistcoat, during the whole of which time she had been raving and talking nonsense, having only had two hours' sleep : and there was the prospect of her remaining several days longer in the same condition. There were several epileptics in the ward, and one of them had a, fit while we were present, and there were imbeciles and demented watching all this with curious, half-frightened looks, which said very plainly how injurious the whole scene must be to them. We are willing to suppose that the guardians of Clerkenwell are unconscious of the great cruelty of allowing this wardful of women, who never ought to be associated, to sit gazing helplessly at each other, with no amusement but needlework, which they probably hate ; or of leaving a melancholic patient whom we saw in the male ward (and whose condition was assuredly improvable) to mope, with his head in his hands, the livelong day. For our own part, we have never seen a sight which more thoroughly shocked us by its suggestions of the unlimited power of stupidity to harass and torment the weak and sensitive. But assuredly the stupidity and the ignorance are in this case a fresh crime, for no one who undertakes to manage the insane has any right to plead ignorance of the conditions necessary to their welfare.

The defects of the Clerkenwell Workhouse are so manifest, the house is so clearly unfitted for the purpose to which it is applied, that it might be supposed that nothing but intentional cruelty could lead the guardians to the policy of retaining it. They have bad many opportunities in past years of selling their property for a sum which would readily have purchased a site in their own parish, and paid the expenses of a proper new building. But they have constantly refused to take advantage of this, and have continued their present residence till it is now almost certain that when they are forced to a removal they will have to take their workhouse out of the parish.

We sum up our observations, therefore, in the same tone as that in which we concluded our report on St. Martin's. There is no remedy for the evils of Clerkenwell Workhouse but immediate removal, and the sooner the guardians put their house in order with a view to that course the better.

The outcry that The Lancet articles provoked was a significant factor leading to the passing of the Metropolitan Poor Act in 1867. The Act introduced major changes in the provision of care for London's sick poor and also resulted in the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB).

In 1868, the newly formed MAB set up six new Sick Asylum Districts for the purposes of providing hospital care for the poor on separate sites from workhouses. One of the new Districts, named Finsbury, comprised the Holborn Union together the parishes of St James & St John, Clerkenwell, and St Luke's. However, the large new hospital required by the new scheme was felt to be too expensive and in 1869 the Finsbury Sick Asylum District was reconstituted as an enlarged Holborn Union.

After Clerkenwell's absorption into the Holborn Union, the increasingly dilapidated Farringdon Road workhouse continued in use until 1879 as accommodation for elderly and infirm paupers.

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Islington Local History Centre, Finsbury Library, 245 St John Street, London EC1V 4NB. Holdings for Clerkenwell: Settlement Examinations (1777-1851); Food Books (1859-69); Vagrants Admitted (1858-66); Indoor Relief (1852-69); Admissions and Discharges (1847-71); Medical Relief (1851-69).

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Holdings for Clerkenwell: Guardians' minute books (1868-70).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- History and Description of the Parish of Clerkenwell by J & HS Storer and T Cromwell. 1829.

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.