Strand, Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

The parish of St Anne's, Soho, had a workhouse from at least 1697 on Symbell's Alley. Between around 1711 and 1766, the workhouse was located on the site of what is now 103a Oxford Street. In 1766, an establishment briefly operated on Chapel Street (now Great Chapel Street) but was almost immediately succeeded by one on Hog Lane — now under Charing Cross Road. Between 1771 and 1837, when it joined the Strand Union, St Anne's had a workhouse on Rose Street, now 14 Manette Street. The building, designed by James Paine, had an extra storey added in 1804.

Manette Street, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

The parish of St Clement Danes operated a workhouse from 1771 to 1836 at the Junction of Portugal Street and Carey Street, now the site of Strand House.

The Precinct of the Savoy was the location of Henry VII's Savoy Hospital on the Strand, on the site of John of Gaunt's palace. It provided care for the homeless between about 1512 and 1702. Between about 1790 and 1801 it occupied the Great White House at Hoxton.

The Liberty of the Rolls is believed to have had a workhouse on Elm Street, Gray's Inn Road, from around 1737. It later had an establishment in Bird's Buildings, Lower Street, Islington (now Essex Road to the east of Islington Green).

The parish of St Mary le Strand may have had a workhouse at Denham's yard prior to 1762. From about 1762 to 1768 it had houses on New Street, Shoe Lane (now Little New Street) and Shacklewells in Hackney. Later establishments were at Garratt Lane, Tooting from about 1777-1801, at Swan Yard and then George Yard (both now the site of India House, Aldwych) from about 1781 to 1800, at Great White House in Hoxton in 1801, and at Robertson and Simpson's house also in Hoxton in about 1801-2. From 1811 to 1836, the parish had a workhouse on the Old Kent Road, now the site of Leo Street and Clifton Crescent.

St Paul, Covent Garden, had a workhouse from 1702 until the 1720s on Hart Street (now Floral Street) followed by a nearby one at the corner of Hart Street and Bow Street, now the site of the Royal Opera House. From 1734-78, the workhouse was on Denmark Court (now part of now Exeter Street), at the rear of 14 Tavistock treet) — this building collapsed in 1787. From 1778-1836, the parish workhouse stood on Cleveland Street, erected via a Local Act of 1775 (15 George III c.50) "to enable the Inhabitants of the Parish of Saint Paul Covent Garden, in the County of Middlesex, to purchase or hire a convenient Piece of Ground, for the Purpose of erecting a Workhouse thereon for the Reception and Employment of the Poor of the said Parish; and for providing an additional Burial Ground for the Use of the said Parish."

Covent Garden workhouse site, 1827.

The Cleveland Street workhouse has a strong claim to be the inspiration for the establishment portrayed in Charles Dickens' novel Oliver Twist. For two periods in his life, amounting to five years or more in total, Dickens' family lived at 10 Norfolk Street, now 22 Cleveland Street, less than ten doors away from the workhouse.

After 1834

The Strand Poor Law Union was formed on 25th March 1836. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 21 in number, representing its 5 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

Middlesex:

St Mary-le-Strand, with the Duchy of Lancaster (3); Precinct of the Savoy; St Paul, Covent Garden (5); St Clement Danes (10); Liberty of the Rolls (2).

Later additions: St Anne, Soho (1837), St Martin-in-the-Fields (1868).

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 26,220 with an average (1833-35) poor-rate expenditure of £14,306.

Cleveland Street

The new Strand Union took over the former St Paul's Covent Garden parish workhouse on Cleveland Street. The buildings extended to the east, with the Poor Law Commissioners authorising expenditure of £263 in 1836 and £1,500 in 1839. The layout of the buildings in 1870 is shown on the map below. The main block, at the centre of the site, was a four-storey U-shaped block, with its entrance on Cleveland Street at the south-west. At this date, the ground floor rooms were largely used as infirm wards, with females housed at the north of the site and males at the south. A wash-house and laundry stood on the women's side, with workshops on the men's side at the southern perimeter. There was also a large chapel.

Strand Cleveland Street site, 1870.

The burial ground continued in use until 1853 when it was closed by an Order in Council.

In March 1844, it was reported that in the men's sick ward there were seventeen inmates whose combined ages, together with that of the nurse, amounted to 1,169 years. The female inmates were equally long-lived — four women buried in a recent ten-day period had respective ages of 86, 84, 82, and 76.

From 1856, the union's Medical Officer was Dr Joseph Rogers who received a salary of £50, from which all drugs had to be paid for. Rogers described the Cleveland Street building as:

When Rogers arrived at Cleveland Street, whose inmates never numbered less than 500, a number of things gave him cause for concern:

- Carpet-beating was continually performed by able-bodied inmates just outside the male wards, with much resulting noise and dust.

- There were no paid nurses and nursing was performed by elderly female inmates who were often drunk.

- The ward for fever and foul (venereal) cases had only two beds and was separated from the tinker's workshop by a thin partition.

- The nursery was damp and overcrowded.

- The laundry was located in a cellar beneath the dining-hall and filled the building with unpleasant-smelling steam.

Rogers gained the Guardians approval for removing the laundry to the rear yard of the workhouse. This turned out to be a more complicated exercise than expected because the digging of the new laundry foundations revealed large numbers of skeletons were found under the old burial ground. Digging had to continue to a depth of twenty feet before solid ground was reached. Rogers also had the cellars enlarged to provide better accommodation for sick children and for casuals, something that made him unpopular with some of the Guardians who delayed increasing his salary for two years. He also received criticism from the Guardians after increasing the gruel-only diet fed to single mothers for nine days after giving birth in the workhouse labour ward.

One of Rogers most persistent problems at Cleveland Street was the workhouse master, a former policeman and workhouse porter named George Catch. Catch, and his wife who was workhouse matron, treated the inmates badly and also obstructed most of Rogers' efforts and improving conditions in the workhouse. Rogers finally managed to secure Catch's dismissal after his extreme neglect of a woman who was severely ill in the lying-in ward. Catch had refused to call up Rogers to attend the woman so that he would not receive a fee for doings so. Catch was then dismissed from his post.

In 1853, Louisa Twining was granted permission by the Board of Guardians to visit an elderly acquaintance in the Cleveland Street workhouse. Her discovery of the feelings of neglect experienced by the inmates led her to set up a scheme for her friends to visit inmates at the Strand and other workhouses. After the Poor Law Board expressed reservations about such activities in 1857, the Strand Guardians withdrew their permission for the scheme. However, Twinings campaign for better access for visitors to workhouses led, in 1858, to the founding of the Workhouse Visiting Society.

In 1865, the Strand was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal The Lancet investigating conditions in London workhouses and their infirmaries. The report, extracts from which are included below, contained numerous criticisms of the conditions and practices that were found.

The problems which are presented by the statement of these primary facts are most grave. Deeply saddening is the conviction that the great mass of in-door pauperism in the Strand Union is weighted with the additional burden of sickness — too often hopeless as to prospects of cure. But, apart from compassionate sentiment, our instinctive feelings of duty force on us the reflection that the resources of one of our great voluntary hospitals, of the first, or at any rate of the second rank, would not be too large or powerful to deal competently with the needs of the sick in this workhouse. Let us inquire how far these needs are met by the present arrangements.

...

In this great workhouse hospital we find that there are, for all purposes of superintendence, a master and matron, who do indeed happen to be unusually intelligent, active, and humane, but who are seconded by no paid nurses whatsoever! There are twenty-two pauper nurses, and twenty-two pauper helpers. Of the former, very few can be considered fitted for their work as far as regards knowledge, and many are mainly incompetent from age or physical feebleness. The helpers are, of course, mere ignorant drudges. And yet this nursing staff has to minister to the wants of a sick population, which on the 28th of January last amounted to nearly 200 sick, besides 260 infirm or insane. A greater disproportion between requirements and resources it would be difficult to imagine; yet we hasten to admit that, in consequence of the moral tone given to the establishment by the master and matron, and by the benevolent lady visitors, and of the vigilance of the surgeon, there appear to be few or none of the grosser negligences about personal cleanliness of patients, and other vital points in ward management, which we have noticed in some other houses. But beneath the surface there must be grave defects. For, instance, there is no organized system of night-nursing — nothing but occasional paupers appointed for the moment, and supervised by the matron, who, we believe, really exercises extraordinary activity to perform the work of a night-superintendent, which never ought to have been thrust upon her, and which it is quite impossible that she can adequately carry out. The nursing arrangements, then, may be said to be thoroughly inefficient and improper. The wards are low-pitched and gloomy. In the two "sick wards" it is true there is an average of 748 cubic feet space to each bed, and the appearance of these wards is tolerably cheerful, but being in the roof, with no ceilings, they must be dreadfully hot in summer weather; and as for the remainder of the wards, they do not average an allowance of more than 450 cubic feet per bed. Nor is this radically defective ventilation improved by well-constructed staircases, capable of admitting currents of air to circulate through the buildings; on the contrary, the staircases are narrow, and they wind in acute angles, so that the atmosphere which they contain is stagnant, and there is a general frowsiness perceptible throughout the house. The beds on which the patient's lie are of flock, thin, lumpy, and wretched; and there are no lavatories or bath-rooms attached to the wards, nor is it easy to see how they could be added, owing to the faulty construction of the buildings The water-closets are tolerably numerous and good, but they are awkwardly placed with regard to the wards.

...

The medical attendance upon the sick in the Strand Workhouse is a subject at once interesting and painful. It has never in the whole course of our inquiries fallen to our lot to observe a more pointed instance of hard and bitter service by a faithful officer, requited by scanty pay, and persistent opposition on the part of the higher authorities to his conscientious recommendations and exhortations to improvement in the construction, management, and arrangements of the house. Dr. Rogers receives the munificent salary of 105l. per annum, the guardians finding cod-liver oil and lemon juice, and 30l. a year towards the remaining expenses on the score of drugs — a very scant allowance for the latter purpose. The work which has to be done is greatly in excess of what any one man could perform who has to look to private practice for the means of supporting himself, towards which, of course, the above-mentioned salary is a ridiculous bagatelle. Besides the large number of patients whom he has to attend to, the medical officer has to dispense the medicines, and he must utterly break down in his duties were it not that he employs his own paid assistant to help him for some hours daily in the performance of the guardians' work. The result of this self-sacrificing conduct is, that although there are necessarily some defects in the medical management of this huge hospital, a nearer approach is made to theoretical perfection in this respect than could possibly have been expected; and in particular we have to mention that the surgical dressings (a tedious and laborious item of medical attention) are well and sufficiently applied, and that there are none of those painful deficiencies in this respect which we have had to record in our report on Shoreditch. We have already noticed in our general report the useful innovation which Dr. Rogers has induced the guardians to carry out, in the shape of a special dietary for the infirm, itself an enormous boon to a large class of sufferers.

So far it may seem, on the whole, that we have had to speak with equally-balanced praise and blame of the Strand Union infirmary and its management. But the side which we now have to approach — the conduct of the guardians in the administration of the house — affords a very gloomy picture. Step by step the internal reforms which we have mentioned have been wrung from them, with infinite difficulty and annoyance to the reformers. But to show how utterly unconscious (or else how wilfully neglectful) of their duties as administrators of a great pauper hospital the guardians are, it is sufficient to enumerate the following particulars. In the first place, their retention of the present buildings, which are so shamefully inadequate, is perfectly unnecessary, since they have long possessed an estate at Edmonton on which a proper workhouse and infirmary might have been built; and they are well aware that their present buildings are entirely unsuited, both as to site and construction, for the functions which they pretend to perform. Secondly, they have been consenting parties to an amount of overcrowding of their house which has been at all times dangerous, and has occasionally, as we shall presently see, borne disastrous fruit. And thirdly, they have been guilty of one special crime against acknowledged sanitary laws which it is impossible to reprobate too strongly: we refer to the maintenance of a carpet-beating business within their walls, already mentioned in our general report. Owing to the extensive additions which have been successively made to the original buildings, the grounds are cut up into a series of narrow enclosed yards, already sufficiently unhealthy; and in one of these, right under the windows of the sick wards, this abominable nuisance of carpet-beating is carried on, filling the air from morning to night with clouds of poisonous dust, which rise to the windows of the wards, and compel them to be closed even when ventilation is most needed, and causing an uproar of noise, which must inflict torments on those who are severely ill, and to whom repose is so necessary. Against the iniquity of this proceeding various persons have from time to time ineffectually protested... but meanwhile the business brings in 600l. a year. This last consideration has proved altogether too much for the guardians of the Strand Union.

...

The Strand Union infirmary has but one redeeming feature—the care and skill of the surgeon and of the master and matron, and the improvements in ward management which the zeal of these officers and the benevolence of the lady visitors have effected. The buildings are atrociously bad as a residence for sick persons, and they are incapable of real improvement by any cobbling process. The nursing is utterly insufficient; nor will the introduction of one paid nurse, which we understand is about to take place, effect any considerable improvement, any more than it has done at Shoreditch. Such a limited measure of reform is a mere farce. Proper classification is impossible: The insane are miserably ill-provided with lodgement, and not at all provided with the occupations proper to their condition. And, finally, there is a board of guardians composed of men who are doubtless excellent in their private capacity, but who, as a board, have neglected some of the most ordinary sanitary precautions, who exact a fabulous and impossible task from their miserably underpaid surgeon, and who, with one or two exceptions, have unfortunately placed themselves on the side of resistance to the reforms suggested by medical science, and indeed by common humanity. It is impossible to account for such resistance by any other supposition than this, that they have altogether failed to appreciate the position of special responsibility in which they are placed as guardians of one of the most miserably diseased collections of humanity which even the London workhouses could show. They partly cannot, and partly will not, see that they are directors of a great hospital, and that it rests with themselves to occupy a prominent position, either in public estimation or public condemnation, according to the way in which they administer this great trust. The practical conclusions to which we are finally conducted are these; that the Strand infirmary ought to be rebuilt on modern principles, on a healthy site; and that the present governing body ought to be greatly modified, if it is to continue to administer the affairs of a great pauper hospital.

The outcry that The Lancet articles provoked was a significant factor leading to the passing of the Metropolitan Poor Act in 1867. The Act introduced major changes in the provision of care for London's sick poor and also resulted in the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board.

From around 1873, after the building of a new workhouse at Edmonton, the Cleveland Street site was used as an infirmary by the Central London Sick Asylums District. This arrangement continued until 1913, although in 1901 formal ownership of the site was taken over by the Westminster City Council. After the Sick Asylum District was dissolved in 1913, the premises were leased to the Guardians of the united parishes of St Giles-in-the-Fields and St George Bloomsbury at a rent of £400 a year. From 1916 to 1922, the Metropolitan Asylums Board ran a children's infirmary at the site. The following year, Westminster Council was given permission to dispose of the site through a special parliamentary Act — the Westminster City Council (Cleveland Street Infirmary) Act 1923 (13 & 14 Geo. 5, c.viii).

The site was then acquired by the nearby Middlesex Hospital and was crucially involved in the hospital's rebuilding. The Cleveland Street premises were updated and half of the main hospital's capacity was then transferred there, after which the now empty half of the hospital building was demolished and reconstructed. The process was repeated with the other half of the hospital.

Cleveland Street, 1926

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cleveland Street refurbished ward interior, 1926.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Cleveland Street building was in use as the Middlesex Hospital's out-patients department until 2006. The building was then left empty, but when its demolition appeared likely a campaign was launched to preserve it. This resulted in the listing of the building by English Heritage in 2011. The front section of the building has now been converted to residential use, while the rear parts of the building have been demolished.

Cleveland Street from the south, 1930s

Cleveland Street rear wings from the west, c.2008

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cleveland Street rear wings from the east, c.2008

© Peter Higginbotham.

Cleveland Street mortuary (left), c.2008

© Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Workhouse

In 1868-70, in the wake of the damning criticism of Cleveland Street, the Strand Union erected a new workhouse at Edmonton, at a site immediately to the north of Edmonton Union workhouse. Its location and layout are shown on the 1914 map below.

Strand, Edmonton workhouse site, 1914.

The building comprised two long parallel blocks, linked by short cross ranges. Lodges stood either side of the entrance on Silver Street at the north. The main block was three storeys high, with a chapel to its rear separating the male and female sides. A third block to the south may have been an infirmary with a mortuary at its southern side.

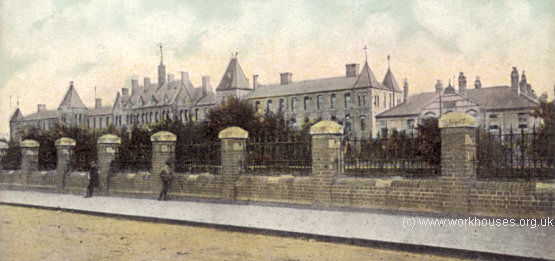

Strand Workhouse at Edmonton from the north-west, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Strand Workhouse at Edmonton from the north-west, c.1905.

Strand Workhouse at Edmonton from the south, c.1930.

In 1901, A man named Duncan Cumming spent a few weeks in the workhouse and recorded his impressions of the establishment. Here is his description of the inmates' food:

The full version of Cummings' account can be read here.

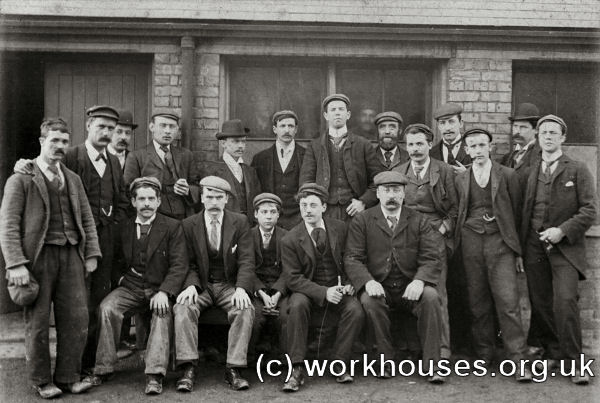

A group of male staff? Strand Workhouse at Edmonton, early 1900s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

During the First World War, the workhouse was used to house Belgian refugees.

Strand Workhouse at Edmonton, from the north - entrance to Belgian Refuge, c.1915.

Strand Workhouse at Edmonton, - entrance to Belgian Refuge (detail), c.1915.

After its closure as a workhouse, the buildings were used as a factory making stockings and other garments, and was called Klingers. The Strand's Edmonton workhouse buildings no longer exist.

Millfield House School

In 1849, the Strand Board of Guardians decided to open a union school and acquired a property known as Millfield House on Silver Street in Edmonton, about a quarter of a mile from the workhouse. The house was an old mansion with large wooded gardens and surrounded by grasslands. In 1863, more land was purchased and alterations and additions made to the old house. Two infirmary blocks were added in 1878, and in 1889 £13,000 was spent on further extensions. The site location and layout in 1912 are shown on the map below.

Strand, Millfield School site, 1912.

The main block, which comprised the old mansion and its extension, contained the boys', girls', and infants' schoolrooms, together with the dining hall. The eight boys' dormitories were on the first floor in the main block. The girls had six dormitories — three in the old house and three in the extension. At night, the children kept their clothes in a small basket placed under each bed.

Strand, Millfield House School main block from the north-west, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

At the west of the site, one infirmary served general cases, the other was reserved for the treatment of ophthalmia, a disease of the eye, which was common in pauper schools. Other buildings included an isolation cottage, a probation lodge, a superintendent's house, and a porter's lodge. A swimming bath, 54 feet by 18 feet in size, was converted into a playroom for the girls during the winter months.

Strand, Millfield House School entrance from the north-west, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school could accommodate almost 400 children and on 22nd July 1897 the 338 inmates comprised 168 boys, 130 girls and 40 infants. As well as children from the Strand Union, the school also took children from the St Giles, Hackney and West London Unions. Children destined for the school first spent two weeks in the main workhouse, then were despatched in fortnightly batches to the school. They then underwent a further 28 days probation before joining the main body of the school.

Boys were addressed by their surnames and girls by their Christian names. Boys were taught history and geography, drawing, and singing by note. Girls received conversation classes, learned needlework, and were taught to sing by ear. To equip them for later life, the older boys were trained in tailoring, shoemaking and carpentry. Participation in he school band gave some of the boys the possibility of a future career as military musicians. The girls learnt laundry, cookery and household work which would enable them to enter domestic service. Some girls were trained to assist in caring for the infants in the nursery.

For recreation, the girls had toys, swings and skipping ropes, and swimming in summer. By the 1890s, they were occasionally taken out for holidays and sight-seeing, and had their own museum. The boys had an open-air gymnasium and sports field and a covered playground for wet weather.

In 1896, a dentist was appointed to make weekly visits to the school. All the children's teeth were examined at least every three months.

Strand, Millfield House School outbuilding, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

An old photograph, dated 12th July 1905, shows "The Strand Union Band" — presumably from Millfield School — at the Children's Fête at The Vicarage, Tottenham.

Strand Union Band, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The school closed in 1913 and at the start of the First World War housed Belgian refugees.

Millfield House Belgian Refuge, 1914.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1915, the Metropolitan Asylums Board took over the site and converted it for use as a colony for up to 300 male "sane epileptics". (A similar number of female epileptics was accommodated at a home Brentwood under an arrangement with the Hackney Board of Guardians.) The site was taken over by the London County Council in 1930, and in around 1936 was renamed St David's Hospital. The hospital finally closed in 1971.

In more recent times, the Millfield House site has been used as an arts centre. The entrance buildings, main house and a few other blocks survive.

Bear Yard and Sheffield Street

In 1890, the union built casual and receiving wards at Bear Yard, Sheffield Street, the latter department used to house paupers prior to transfer to Edmonton. The buildings were demolished in about 1900 as part of an improvement scheme. In 1903, a replacement building was erected fronting onto Sheffield Street.

Men queuing for admission at Sheffield Street workhouse, c.1900.

Strand, Sheffield Street site, 1937.

In 1913, the Strand Union amalgamated with St George's Union and Westminster Union to form the new City of Westminster Union. Following this, the Sheffield Street Hospital was sold to the Metropolitan Asylums Board for £20,000. During the First World War, it was used as an observation hospital for war refugees then, in 1920, was adapted for use as a hospital for women and girls suffering from venereal diseases. The larger block at the south, known as Sheffield House, contained office and staff accommodation, and the laundry in the basement. The north block contained the kitchen and patients' dining room in the basement, treatment rooms on the ground floor, and wards on the upper floors.

Strand, Sheffield Street from the north-east, 2004.

© Peter Higginbotham.

After 1929, the hospital came under the control of the London County Council who created extra wards in Sheffield House. Its name was also changed to Sheffield Street Hospital. After 1948, the hospital became part of the National Health Service as St Philip's Hospital and later specialised in nephrology cases. In more recent times, the building was occupied by the London School of Economics but was demolished in 2011.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

City of Westminster Archives Centre, 10 St Ann's Street, London SW1P 2DE.

- St Anne, Soho — holdings include: Board of guardians overseers' minutes (1849-1900), Overseers' accounts (1719-1860), Settlement papers and removal orders (1736-1835, indexed), Indemnification bonds (1686-1742), Petition for poor relief (1822), Miscellaneous letters and orders (1782-1822), Workhouse admissions list (1781-2), Workhouse work books (1785-1838), Workhouse administrative records and accounts (1781-1836), Apprenticeship register and indentures (1686-1834), Bastardy registers (1790-1825), Records of poor children and nursery (1789-1793,1818-1838).

- St Clement Danes — holdings include: Overseers' and churchwardens' minutes (1779-1850, 1878-1900), Overseers' accounts (1604-1900), Settlement examination books (1703-07, 1739-1836, indexed 1739-1836), Settlement registers (1699-1707, c1715-1750), Settlement and removal legal papers (1806-1836), Settlement certificates (1701-71), Petitions for poor relief (1809-1836), Lists of workhouse inmates incl. admission and discharge details (1785, 1834), Workhouse clothing books (1785-1796), Workhouse administrative records/accounts (1788-1834), Bastardy examination books (1786-1798, 1809-1818 indexed), Bastardy bonds (1641, 1705), Records of poor children and nurses (1719-1727,1767-1822), Nursery accounts (1832-1836).

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- Cleveland Street holdings: Admissions and discharges (1856-1913).

- Edmonton workhouse holdings include: Admissions and discharges (1870-1913); Baptisms (1884-1927); Deaths (1903-13); etc.

- Sheffield Street receiving workhouse holdings include: Admissions and discharges (1890-1913); Creed registers (1908-13); Births (1890-1913); Deaths (1890-1913); etc.

- Edmonton (Millfield) School holdings: Admissions and discharges (1851-1913); Creed registers (1875-1913); Attendance registers (1894-1904).

- Other holdings include: Guardians' minute books (1836-1915); Financial records (1846-1910); Staff records (1856-1913); etc.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- The Lancet, August 12, 1865.

- Locations of Westminster's Workhouses and Infirmaries (Information Sheet 12, Westminster City Archives, 2003).

- Poor Law Records (Information Sheet 13, Westminster City Archives, 2003).

- Richardson R and Hurwitz B (1989) Joseph Rogers and the Reform of Workhouse Medicine (Br Med J, 299, pp.1507-10)

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.