Edmonton, Middlesex

Up to 1834

Edmonton erected a parish workhouse in 1731-2 at the south side of Church Street, immediately to the west of All Saints Church. The building was demolished in the 1840s.

Poor relief in Enfield dates back to at least 1630 when Robert Curtis was paid for setting the poor to work. A workhouse was set up in leased premises at Chase Side in 1719. The building was bought in 1740 and later extended with the addition of a school-room by 1788 and a pest-house by 1802. In 1765, the poor were farmed out to a contractor. All paupers were required to wear a uniform and pauper's badge on their shoulder. From 1806, children were sent from the workhouse to work at a silk factory at Sewardstone in Essex. The workhouse was replaced by a new building on the Chase Side site in 1827.

Hornsey had a workhouse in operation by 1730.

Tottenham's workhouse was built on Tottenham High Road in about 1763, with an additional wing being added to the building in 1818. The property was later known as Coombe's Croft House.

A parliamentary report of 1777 recorded the operation of parish workhouses at Edmonton (for up to 76 inmates), Enfield (70), Hornsey (30), Tottenham High Cross (60), and Cheshunt (70).

After 1834

Edmonton Poor Law Union formally came into existence on 3rd February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 38 in number, representing its 7 constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate number of Guardians where this was more than one):

Middlesex: Edmonton (6), Enfield (8), Hampstead (6), Hornsey (including Highgate) (4), Tottenham (5).

Essex: Waltham Abbey (4).

Hertfordshire: Cheshunt (5).

Later additions (from 1894): Southgate, Wood Green.

The population falling in the Union in 1831 had been 46,510 — ranging from Waltham Abbey (4,104) to Enfield (8,812). The average poor-rate expenditure for 1833-5 had been £13,779 or 8s.5d. per head of the population.

One of the first tasks of the new Board of Guardians was to review its workhouse accommodation. It had inherited seven parish workhouses, four of which were identified as potentially useful: Edmonton (200 places), Hampstead (200), Enfield (140), and Tottenham (150). The others were ruled out for various reasons: Hornsey was very dilapidated; Cheshunt was new but badly built and was dark, damp and inconvenient having been built to close to the flood plain of the river; Waltham Abbey was unfit for use. Tottenham, was ruled out, since it appeared not to be owned by the parish. The union therefore decided to accommodate able-bodied adults in the old Edmonton workhouse, with the former Hampstead parish workhouse being used for the aged and infirm, and children going to the former Enfield parish workhouse. The others were then disposed of. Extensive alterations and improvements were put in hand at Enfield, and additional land acquired. However, the Board then decided to replace the old Edmonton and Hampstead houses with a new purpose-built workhouse at Edmonton.

The Edmonton Workhouse and Infirmary

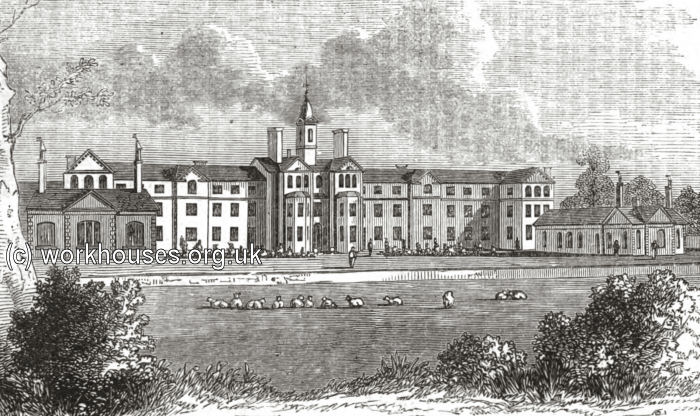

The new Edmonton Union workhouse was built in 1839-41 at Tanners End in Edmonton, with Bull Lane running along the west of the site and Bridport Road at the south. Intended to accommodate 500 inmates, the new building cost £15,819 and opened in January 1842. The Elizabethan-style building was designed by the partnership of George Gilbert Scott and William Bonython Moffatt who were the architects of many other English workhouses. The location and layout of the Edmonton workhouse are shown on the 1914 map below:

Edmonton workhouse site, 1914.

Edmonton workhouse from the south, c.1844.

©Peter Higginbotham.

A report in 1844 noted that three of the site's five acres had been successfully brought into cultivation by the workhouse master, Mr Barroclough, with quantities of potatoes and winter greens being produced. It was the practice of the house to rouse the inmates at 6.45 a.m, followed by prayers at 7. At 7 p.m. the inmates were again assembled to hear prayers, after which the bedrooms were opened and they could retire to rest as soon as they pleased. They were, however, not required to withdraw immediately, but generally availed themselves of the privilege with little delay. For the most part all were in bed by eight o'clock, at which hour the fires were put out and the lights extinguished. The aged and infirm were permitted to promenade the fine grounds in fair weather during the whole of the day, being kept apart from the young and the dissolute, who might annoy or disturb them.

In 1848, Hampstead separated from the Edmonton Union to become an independent Poor Law Parish and run its own workhouse.

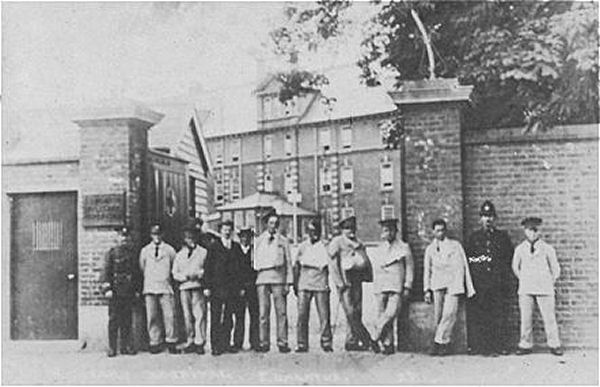

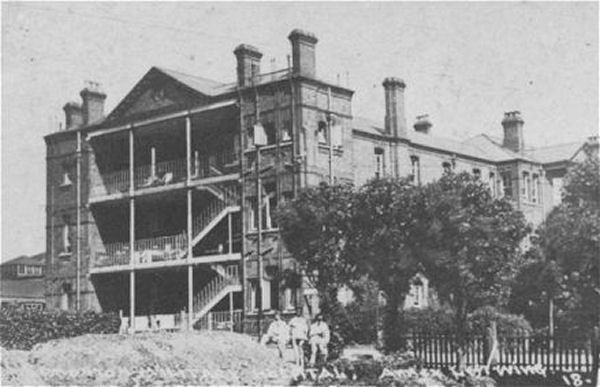

In 1910, a pavilion-plan infirmary was erected on fields at the east of the workhouse, separated from it by a long fence. The infirmary became Edmonton Military Hospital during the First World War.

Edmonton workhouse infirmary from the west c.1912.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Military Hospital from the west c.1917.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Military Hospital circa 1917.

Edmonton Military Hospital from the south c.1917.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse gave its address just as 77 Bridport Road, Edmonton UD.

Edmonton workhouse from the south, c.1928.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Pat Cryer's grandfather was the labour master at Edmonton workhouse. His son Edward, Pat's uncle, recorded that:

The former workhouse later became Edmonton House, and then under the National Health Service as the North Middlesex Hospital. Most of the old workhouse buildings have now been demolished and replaced by a car park but a ward block and several other smaller blocks survive at the south of the site.

Edmonton former site entrance from the south, 2001.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton ward block from the south, 2001.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton administrative block from the west, 2001.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The Union School at Enfield

The old Enfield parish workhouse at Chase Side was taken over by the Edmonton Union for use as a school. It was extended in 1839-42 and an infirmary added in 1844. The main building was three storeys high with an E-shaped layout with its entrance facing to the west. Other buildings included a chapel and mortuary.

Edmonton Chase Side school site, 1866.

The health of the children in the school was a constant cause of concern. In a twelve-month period in 1837-8, there were outbreaks of such conditions smallpox, scarlet fever, ophthalmia, measles, tuberculosis, "the itch", and ringworm. Over that period, there were seventeen deaths out of a total of 150 children. By 1881, the school was overcrowded and discussions took place as to whether the existing buildings should be enlarged or an entirely new school erected at a new site. The latter course was eventually taken and a new school was erected at Chase farm (see below).

The Enfield site was retained by the union however, and it was converted for use as a union infirmary in around 1886. Following the opening of the new infirmary at Edmonton in 1910, the site appears to have been used for the accommodation of the elderly.

Edmonton Chase Side site, 1896.

After 1930, the institution came under the control of Middlesex County Council and up until 1948 was known as Enfield House. It then became part of the National Health Service under the name of St Michael's Hospital, specialising in geriatric care.

Edmonton former Chase Side from the east, 1970s.

©Peter Cracknell.

Edmonton former Chase Side from the east, 1994.

©Peter Cracknell.

Edmonton former Chase Side from the east, 1994.

©Peter Cracknell.

Edmonton former Chase Side from the east, 1994.

©Peter Cracknell.

Edmonton former Chase Side from the east, 1994.

©Peter Cracknell.

The hospital is now closed and all the old buildings have been demolished. Modern housing now stands on the site.

Chase Farm Schools

In 1881, the Edmonton Guardians decided to replace the old Chase Side school with a new building at a different site. To this end, they purchased Chase Farm, to the north-west of Enfield, for the sum of £12,000. The Union's architect, T.E. Knightly, was asked to prepare two sets of plans, one based on the well established pavilion block system, and one on the cottage home system which was just starting to be adopted, for example by the Kensington & Chelsea School District at Banstead in 1880. They Guardians opted for the pavilion block design which would have cheaper building and running costs, and also required also segregation of boys and girls. However, the plan would also include a small number of cottage homes.

Another question pondered by the Board was whether the earth closet or water closet system of sewerage should be adopted. The earth closet system involved each user scattering dry earth into the receptacle after their visit. This was felt to be the superior system, produced valuable fertilizer, and Chase Farm had exactly the type of earth recommended. However, in such a large institution, the full-time services a paid servant would be required to maintain it. Even if the earth closet system was adopted, however, water and drainage pipes would still need to be installed for sinks and baths. In the end, water closets were installed in the main buildings, but earth closets for daytime use were placed in others.

The buildings, intended to accommodate 350 children, were erected in 1884-6 at a cost of £55,063. The schools were officially opened on 27th March, 1886, with a ceremony at which, despite the "intense cold and uncomfortable weather" the children entertained with choral and band music.

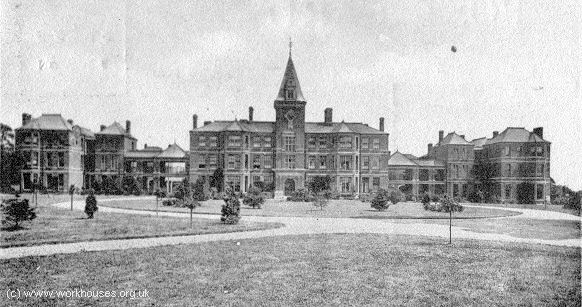

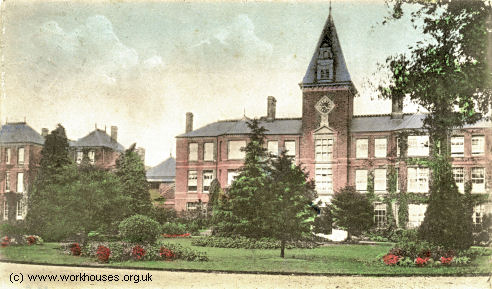

Edmonton Chase Farm School from the south-west, early 1900s.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Chase Farm School from the south-west, c.1910.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The Chase Farm site location and layout are shown on the 1913 map below.

Edmonton Chase Farm site, 1913.

Edmonton Chase Farm site from the south.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The entrance to the schools lay alongside the main road, the Ridgeway, at the south-west of the site. A porter's lodge was placed at the south side of the entrance. To the rear stood a 28-bed receiving ward where new arrivals at the school would spend two to three weeks. On arrival, a child would be sent to the bathroom, stripped of his own clothes, bathed, put into clean clothes, and confined to a dayroom until examined by a doctor.

Edmonton Chase Farm lodge and receiving ward from the north-west, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The probationary ward block, also with 28-beds, lay to the north of the receiving ward. Children moved here from the receiving ward and stayed for another two or three weeks before entering the main school. Depending on the situation of their parents, some children might remain at the school for only a few weeks or months. Others might stay from infancy until they left at fifteen.

Edmonton Chase Farm probationary block from the south, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The main building comprised a central block containing the administrative functions and the master's quarters, with a 146-bed boys' wing to the south and a 130-bed girls' wing to the north. Two-storey corridors linked the children's wings to the central block.

Edmonton Chase Farm main building from the west, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Chase Farm main building, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Chase Farm boys' wing from the east, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

At the rear of the main building lay stores, bakery and kitchens, and the high-roofed dining hall, all lit from above by ridge lantern windows. The final block, at the east of this cluster, contained a swimming pool. The schools' laundry was separated from the swimming-pool block narrow roadway.

Edmonton Chase Farm dining hall, swimming-pool, laundry etc. from the east, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

To the east of the laundry lay a row of workshops and a band-room where the school band practised. Boys who learnt musicianship in the school band might well end up in a military or naval band.

Edmonton Chase Farm band-room from the south, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

An infants' school stood at the north of the workshops.

Edmonton Chase Farm infants' school from the east, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

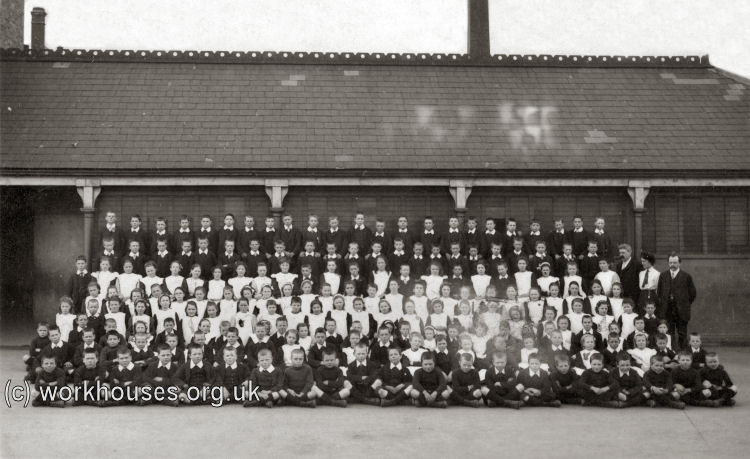

Edmonton Chase Farm infants, c.1900.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Edmonton Chase Farm children, c.1912.

©Peter Higginbotham.

Other buildings on the site included an infirmary, and also — despite the Guardians initial decision — two cottage homes. The comprised two-T-shaped two-storey houses, now joined together to form a single block.

Edmonton Chase cottage homes from the south, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

A later building at the north of the receiving block may have been used for the treatment of conditions such as tuberculosis, ophthalmia and ringworm.

Edmonton Chase Farm medical treatment block(?) from the south, 2004.

©Peter Higginbotham.

The school's Religious Creed register (1887-1907) gives some of the reasons why children had been sent to Chase farm which included:

- Found abandoned, and named after the road in which she was found.

- Mother in prison, five children.

- Mother dead, five children.

- Father in prison, mother dead, four children.

- Mother in hospital, father in asylum, three children.

- Mother dead, father at sea, five children.

In some cases, children would stay at the school until the parent's return form hospital or prison. In the case of a father at sea, the children's stay might be long term although the father would retain parental rights. Where children had become orphaned, the Guardians assumed parental control and the child would probably stay at the school until the age of fifteen.

Most children at the school were registered as Church of England. Roman Catholic children were accepted but caused problems in organsing separate religious instruction for them. In 1900, the local Roman Catholic priest, father O'Gorman, complained that the Catholic children at the school were not attending his church. An investigation led to allegations by three boys that the priest had assaulted them and that they wished to change their religious affiliation. Although the Guardians eventually decided not to take proceedings against the priest, he was barred from visiting children at the school. Roman Catholic parents also became required to request in writing that their children should receive Roman Catholic instruction, otherwise they would be given Protestant instruction.

The Guardians had a responsibility to help children find places when left the school at around the age of fifteen. Boys might aspire to an apprenticeship or joining the services. For girls, domestic service was sometimes an option. Some also found employment is the school, looking after the babies and younger children.

Another solution was to encourage children, particularly those over whom the Guardians had parental control, to emigrate to Canada. This is recorded as taking place in 1887, and again March 1890 when the following list was submitted of those considered 'suitable' for emigration — all girls, it may be noted:

| Fanny Denny | aged 12, deserted |

| Ellen Farley | aged 11, orphan |

| Laura Cullen | aged 12, orphan |

| Louisa Martin | aged 12, orphan |

| Thurza Norris | aged 11, orphan |

| Clara Brindle | aged 12, orphan |

| Emily Mantle | aged 10, illegitimate, deserted |

| Minnie Price | aged 9, orphan |

| Elizabeth Norton | aged 9, orphan |

| Elsie Netch | aged 11, deserted |

| Ada Upjohn | aged 11, orphan |

| Elizabeth Brown | aged 10, orphan |

In April 1890 the required outfits for the journey were ordered to be purchased at a cost not exceeding thirteen pounds per child. The Union then paid a further twelve pounds per child to a Miss Rye who would superintend their travel. The above group were joined by three boys, George Norris, and John and Albert Denny who accompanied their sisters. Later additions to the party were the Burns children and the four Martins who had been deserted. However, before the Martin children were shipped off, their mother, who was living in London agreed to take them and their emigration was cancelled. The Burns boys, too, seem to have dropped out or at least postponed their leaving, as the following letter from Westminster Diocesan Education Fund reveals:

|

Re: James Burns, 14, and William Burns, 10 With reference to your telegram of yesterday suggesting that the names of these boys be takes off the emigration list for next Thursday, and to the visit of your assistant this morning, I write to say profoundly sorry I am that these boys are to be deprived of the excellent opening I have for them in Canada under the supervision of my Montreal agents. From long experience at this work I am fully satisfied that it is an untold blessing for numbers of our pauper children to remove them effectively from their relations who often prove the greatest enemies the children have in their progress in life. I very sincerely hope that the Board will be pleased to raise no objections to my providing for the children's welfare in the way proposed by emigrating. I take this the more confidently because it happens that I am their legal guardian as will be seen by the enclosed instrument which please return to me in due course. Thomas Seddon. |

Later on, Dr Barnardo's was the agency used to send the children to Canada. From 1911-1915, a total of 61 boys and 20 girls emigrated, ranging in age from six to fourteen. On the day that children started their journey to Canada, the school assembly sang the hymn 'For those in peril on the sea'. Some emigrants appear to have been very successful in their new lives — it is said that as late as the 1940s, letters were still being received from wealthy Canadian farmers asking for news of their old school.

In the early 1900s, the Union began to buy houses in the area to use as scattered homes. Each would hold up to 18 boys and 18 girls who would attend local schools as, increasingly, did children from the main Chase Farm site.

In 1930, the schools were taken over by Middlesex County Council who expanded the scattered homes policy. In the late 1930s, moves were made to use the schools to accommodate inmates from the former Edmonton workhouse. With the outbreak of the Second World War, Chase Farm joined the Emergency Medical Scheme to provide care for wartime casualties. After the war, it continued in use as a general hospital under the name Chase Farm Hospital.

Scattered Homes

In 1914, the Edmonton Union was operating children's scattered homes at 71-73 Downhills Park Road, South Tottenham.

Staff

Inmates

- Long-term workhouse inmates (1861)

- 1881 Census - Edmonton workhouse

- 1881 Census - Edmonton Chase Side School

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- Edmonton Union: Guardians' minutes (1837-1930); Lists of paupers (1879-1930); Lists of pauper children (1919-30); Register of emigrants (1925).

- Edmonton House: Births (1886-95); Creed registers (1876, 1881-1938)

- Enfield House: Creed registers (1908-40)

- Chase Farm: Creed registers (1887-1907)

- Enfield Local Studies, Civic Centre, Silver Street, Enfield EN1 3XA. Has Edmonton Board of Guardians Minutes (1908-30, printed).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Boudier, Gary, History of the North Middlesex Hospital, (Enfield Books).

- Graham, M, The Chase Farm Schools, (Edmonton Hundred Historical Society).

Links

- None.

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to Peter Cracknell for kindly providing the Enfield School pictures.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.