Shoreditch (St Leonard's), Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

The first Shoreditch workhouse was at Hoxton in several old houses which were repaired for receiving and employing the poor of the parish. By Michaelmas 1731, the house contained 84 inmates, children and adults, who were employed in spinning mop-yarn. A pack of wool weighing about 240 Pounds and costing £3. 10s. could be sold for around £5 after being made up. One inmate, who could spin Jersey, earned 3d. a pound spinning wool brought to the workhouse ready prepared by a wool-comber. Inmates received three meat dinners a week.

In 1774, Shoreditch obtained a Local Act for 'the better relief and employment of the poor' and for raising money for a new workhouse. Poor relief was placed in the hands of a body known as the Trustees of the Poor and the new workhouse was erected on a site known as the 'Land of Promise' on Kingsland Road, Hoxton. The three-storey building, with its main front on Kingsland Road, opened in 1777. It included an infirmary and apothecary. In 1784, a burial ground for deceased inmates was consecrated at the southwest corner of the site. The labour of the inmates was sold to local businesses (Miele, 1993).

The workhouse incorporated two sick wards. In 1813, James Parkinson was appointed as parish surgeon, apothecary and man-midwife, Amongst other improvements to the medical facilities, Parkinson established a separate fever block in the workhouse, the first in London, for the segregation of infectious patients, particularly those suffering from cholera. In 1817 he published an "Essay on the Shaking Palsy" in which he described the condition we now call Parkinson's Disease.

After 1834

Because its poor relief was administered under a special Act, St Leonard's parish fell outside the jurisdiction of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

In 1847, a Parliamentary sub-committee criticized conditions in the workhouse. It was found to be overcrowded, with 1,000 inmates in accommodation designed for 800, and 150 chronically ill inmates housed in poorly ventilated wards close to the healthy inmates. Concerns were also expressed about the quality of the water supply. In 1849, the Trustees responded with a major modernization of the buildings, with a new accommodation blocks, a new kitchen and bakehouse, and the establishment of an infirmary and fever hospital in a separate wing on Hoxton Street. In November of the same year, the workhouse was the subject of a "Grand Comic interlude" at the Royal Standard Theatre in Shoreditch.

Shoreditch theatre poster, 1847.

© Hackney Archives, 2nd floor, Dalston CLR James Library and Hackney Archives, Dalston Square, London E8 3BQ.

In 1849, the Trustees responded with a major modernization of the buildings, with a new accommodation blocks, a new kitchen and bakehouse, and the establishment of an infirmary and fever hospital in a separate wing on Hoxton Street at the western end of the site.

A further Local Act in 1858 replaced the Trustees by a new body, the Board of Guardians of the Poor, elected in a similar manner to the Boards set up by the 1834 Act. In 1861, the Guardians agreed to comply with an order from the Poor Law Board to erect a new workhouse at Kingsland Road, accommodating 1,200 inmates. The new buildings were designed by a Mr Lee, and cost £47,750. Construction of the new workhouse began in 1863 and was completed in 1866.

Shoreditch workhouse site, c.1873.

The main block of the new building contained the administrative offices, and accommodation for female inmates.

Shoreditch main building from the south-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

To its rear was the dining hall, which also served as a chapel, and dayrooms.

Shoreditch dining-hall and dayrooms from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Male accommodation was located in a cross-wing at the west end of the main building.

Shoreditch male block from the north, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Parish Relief Offices fronted onto Hoxton Road at the west of the site.

Shoreditch relief offices from the west, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In July 1865, during the rebuilding work, Shoreditch was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal The Lancet investigating conditions in London workhouses and their infirmaries. The report, extracts from which are included below, contained numerous criticisms of the conditions and practices that were found.

There are many grievous faults in the present state of things which are incidental to the temporary conduct of building operations in the house. The workhouse and infirmary are being entirely rebuilt, and at a cost, we believe, of about 60,000l. Meanwhile the patients are rather pushed about. Some of the able-bodied are sleeping far too closely packed; and a number of the patients (122, including chiefly the female imbeciles and chronic cases of disease) are temporarily housed at Wapping, in the old condemned and abandoned house of the Stepney Union, which was subjected a few years since to the strictures of Mr. Charles Dickens. Of course, if the latter building, straggling, ill-built, with narrow staircases, low-raftered ceilings, stinking ill-trapped drains, abominable closets, and almost every fault which a house can have, were meant as anything more fault be a great deal to say about the crowding of the patients, the utter cheerlessness and misery of the rooms, and other prominent evils, which could not be tolerated. But as the guardians are pushing forward the completion of their premises at Shoreditch, we shall as far as possible separate the accidental from the essential defects of the arrangements, and treat of them as at their highest existing standard in the best wards at Shoreditch.

The aspect of the wards in the new building is east and vest. The drainage of the building is very good. The wards are not built on the best plan, for they lie each side of a central passage, which is a plan long since condemned; but the passage is lofty and well-ventilated, and so are the wards. The new infirmary is intended for 400 sick, and the imbeciles' wards accommodate 150 more. The average numbers in these two sets of wards now vary from 100 to 350. The males occupy the north end of the building, the females the south end. It is a great recommendation to these wards that they are provided with excellent closets, having separate ventilation into the open air and a dirty-water shoot; that hot and cold water are supplied to each ward; and that there are capital baths and lavatories attached, with self-acting water-taps and enamel basins. Thus in the construction of these wards the guardians have shown liberality and judgment; and the shell is good although the kernel is rotten.

The general aspect of the wards, however, is one of extreme cheerlessness and desolation. This is painful throughout; but it is especially lamentable in the case of the lunatics and imbeciles. Moping about in herds, without any occupation whatever; neither classified, nor amused, nor employed; congregated in a miserable day-room, where they sit and stare at each other or at the bare walls, and where the monotony is only broken by the occasional excitement due to an epileptic or the gibbering and fitful laughter of some more excitable lunatic, - they pass a life uncheered by any of the brightening influences which in well-managed asylums are employed to develop the remnants of intelligence and to preserve them from total degradation. They have here neither fresh air nor exercise, no out-door or indoor occupation of any kind. The exercise-ground is a wretched yard with bare walls, confined in space, and utterly miserable and unfit for its purposes. It is a frightful accumulation of human failures, treated with utter neglect of their human character; kept in tolerably clean rooms, and fed with sufficient food, as we would kennel dogs in decent kennels, but not otherwise recognised or treated as deserving of moral or intellectual consideration. We denounce the cruelty of keeping these imbeciles in a cheerless town workhouse. We protest against their exclusion from the natural blessings of fresh air and exercise, and labour in the open air or in proper workrooms; against the absence of classification; against the total absence of any effort to keep alive the existing glean of intelligence.

In many respects, however, the imbeciles and lunatics are better off in this workhouse than the sick. We have stated that the duties of the medical officer include the charge of the whole of this great population of sick, imbecile, and infirm; and, besides prescribing for them, to dispense their medicines; that there is no resident surgeon, and no dispenser. It will give a startling form to the medical outline if the administration if we add that there are no prescription cards overt lie beds. So that, under this system, the medical officer is supposed to recall to memory, as he passes the bed, the treatment which each patient has had, to make up his mind as to variation, and then, after completing his rounds and on descending into the dispensary, to remember en masse all the changes which he desires to make, and forthwith to prepare the medicines. The medicine-bottles are kept in a mass in a cupboard at the end of the ward with the bread and butter; thus yet further complicating the difficulties even of administering the medicines ordered and supplied.

To make matters as bad as possible, the nurses, with one exception, are pauper nurses, having improved rations and different dress, but no pecuniary encouragements. They are mostly a very inferior set of women; and the males, who are "nursed" by male paupers, are yet worse off. The nursing organization at this establishment is as bad as can be. The male nurses especially struck us as a peculiarly rough, ignorant, and uncouth set. There are no night-nurses. The outer surface of the beds was clean, and the linen generally, through the able-bodied wards, tolerably so; but as to the lying-in wards, they were frequently filthy with crusted blood and discharges, and in the sick wards also they were far from being well kept.

The next part of inquiry was as to the regularity of the administration of food and medicines. Medicines are administered in this house with shameful irregularity. The result of our inquiries showed that of nine consecutive patients, only four were receiving their medicines regularly. A poor fellow lying very dangerously ill with gangrene of the leg bad had no medicine for three days, because, as the male "nurse" said, his mouth had been sore. The doctor had not been made acquainted either with the fact that the man's mouth was sore or that he had not had the medicines ordered for him. A female, also very ill, had not had her medicine for two days, because the very infirm old lady in the next bed, who it seemed was appointed by the nurse to fulfil this duty, had been too completely bedridden for the last few days to rise amid give it to her. Other patients had not had their medicines because they had diarrhoea: but the suspension had not been made known to the doctor, nor had medicine been given to them for their diarrhoea. The nurses generally had the most imperfect idea of their duties in this respect. One nurse plainly avowed that she gave medicines three times a day to those who were very ill, and twice or once a day as they improved. The medicines were given all down a ward in a cup; elsewhere in a gallipot. The nurse said she "poured out the medicine, and judged according." In other respects the nursing was equally deficient. The dressings were roughly and badly applied. Lotions and water-dressings were applied in rags, which were allowed to dry and stick. We saw sloughing ulcers and cancers so treated. In fact, this was the rule. Bandages seemed to be unknown. But the general character of the nursing will be appreciated by the detail of the one fact, that we found in one ward two paralytic patients with frightful sloughs of the back: they were both dirty, and lying on hard straw mattresses; the one dressed only with a rag steeped in chloride of lime solution, the other with a rag thickly covered with ointment. This latter was a fearful and very extensive sore, in a state of absolute putridity; the buttocks of the patient were covered with filth and excoriated, and the stench was masked by strewing dry chloride of lime on the floor under the bed. A spectacle more saddening or more discreditable cannot be imagined. Both these patient have since died: no inquest has been held on either.

With such general and extensive defects in the sick wards of this establishment, it is perhaps undesirable to enter into minor details. We must, however, note the total absence of any attempt to give an air of comfort to the sick wards, or to supply the reality; the entire absence of colour on the walls; the scanty supply of books; the absence of any cheap coloured prints or devices or mottoes on the walls, a pot of flowers in the windows, or of anything that could give a cheerful idea to the mind of the invalid. These are little comforts which cost really next to nothing, but have a considerable and useful influence. Other defects are more openly and decidedly reprehensible. The want of ward furniture especially; the wretched little tables and scanty forms are so insufficient for the number of patients, that they have to eat their dinners on the beds-a habit which is slovenly and improper for patients who are up and can move about. There is a marked absence of chairs, and especially of plain wooden arm-chairs, which are an almost essential comfort for infirm and semi-paralytic patients not absolutely confined to bed. The deficiency of bed-pulls, by which the sick can raise and shift themselves, and the want of so much as a shelf at each bed, on which the wine or brandy, the medicines, or the necessaries of frequent use, may be kept at hand, were pointed out by us: and we were told that such things near the bed "bred vermin." An extensive hospital experience enables us to say, however, that with ordinary care they do not afford lodgment for anything of the sort; and the absence of this species of dumb waiter is much felt by the helpless sick.

The total expenditure here for drugs, including quinine, cod-liver oil, &c., was stated to be about 50l. per annum. At the much smaller infirmary which we have presently to describe, it is more than that per quarter.

The dietaries, on the whole, were up to the average, with the exception that the patients get a great deal too much of boiled meat and too little roast; that the dietary is extremely monotonous, anti that owing to the unusual number of sick to be looked after, and the consequent trouble of frequent special changes, the acutely sick get far too little variety of diet, and are kept too long upon the same thing.

A severe commentary on the nursing staff is supplied by the information given to us by the master, that the average age of the nurses is sixty, and their average duration in office from six to nine months. Remember that these are pauper inmates, commonly without special training; that the men are nursed by males, and how overworked and underpaid the doctor is, and the key will be readily found to many of the abuses which we have described. Where there are so many glaring defects it were unwise to refer to smaller matters, or there are many minor points to which we should further advert, such as the want of bed-rests for patients who could sit up in bed for an hour or two occasionally, of foot-rests or stools, of stomach and feet warmers, and so on. But we have said enough, as we believe, to show that there exists a necessity for broad and sweeping reforms.

The outcry that The Lancet articles provoked was a significant factor leading to the passing of the Metropolitan Poor Act in 1867. The Act introduced major changes in the provision of care for London's sick poor and resulted in the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board. The Act also led to the abolition of London's Local Act parishes and in 1868 the Guardians were reconstituted as a Board under the New Poor Law.

In 1871, the Shoreditch Guardians spent a further £10,000 on additions and alterations to provide an infirmary and dispensary in a separate building (now demolished) at the north-west of the site. An account of the building appeared in The Builder in 1871.

INFIRMARY AND DISPENSARY, SHOREDITCH.

THIS building is being erected at the angle of Hoxton High-street and Reeves-place, and is an extension of the workhouse, which was built about nine years ago. Its length is about 164 ft., and breadth 27 ft.; the height is 54 ft. The ground-floor is devoted to the dispensary, waiting-room, consulting-rooms, surgery, and necessary stores. The upper floors are divided into two wards, 72 ft. by 24 ft. each, with the necessary conveniences, nurses' rooms, &c., ventilated by air-gratings and hoppers formed in the sashes, also by the Galton stoves. Accommodation is provided for 150 beds.

Doctors' rooms, also rooms for matron and assistants, and convalescent rooms for men and women are provided on the upper floors by raising the existing adjoining buildings. It is faced with Gault bricks, Fareham bricks being used for the arches and strings. Greenmoor stone is need for the sills and all interior work, and Portland for the porches, the columns being Red Mansfield.

The works are being carried out under the architect, Mr. William Lee, Gresham-buildings, by Messrs. Hill, Keddell, & Waldram, at a cost of 11,000l.

The new building opened in 1872 and a Matron was appointed for the first time. A later Assistant Matron was the First World War Heroine Edith Cavell who was executed in 1915 by the Germans for helping British prisoners to escape.

In 1930 the London County Council took over the running of St Leonard's, the workhouse was closed and the buildings incorporated into the infirmary which, after 1920, was known as St Leonard's hospital. In 1934 the buildings were condemned but the outbreak of the Second World War prevented any improvements being made. St Leonard's is believed to have been the first London Hospital to receive air-raid casualties and was itself bombed in 1941.

St Leonard's Hospital site from the north, Shoreditch, 1980s.

St Leonard's Hospital site from the north, Shoreditch, 1980s.

St Leonard's Hospital site from the north, Shoreditch, 1980s.

St Leonard's remained a general hospital until 1984 when the in-patient facilities were closed. Since then it has been developed as a centre for co-ordinating community services and supporting health centres.

Enfield School

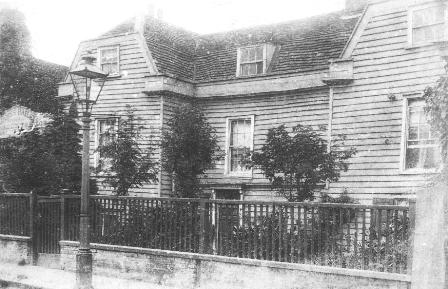

In 1848, Shoreditch instituted its first separate school at Enfield which the 1855 Post Office Directory describes as the "nursery to Shoreditch workhouse" with Joshua Briggs as Master. The building stood on Baker Street alongside the Jolly Butcher public house at the north of Enfield Town and was of weatherboard construction with a red tiled roof.

Shoreditch Enfield School

It appears to have originally been a private residence, but had been purchased before 1829 by the St. Leonard's parish overseers who added cottages at the rear during that year. After the opening of the Brentwood Industrial School site in 1854 (see below), the premises appears to have been returned to residential use and in 1901 were occupied by James Bailey, a removals contractor who used the yard at the rear for his business premises. The building was later numbered 164 Baker Street and continued to stand until c.1967, when it was compulsorily purchased and a block of flats erected on the site of the house, with a special school constructed over the yard.

Shoreditch Industrial School

In 1852-4, the Shoreditch Trustees erected an industrial school on the north side of Brentwood Hill. It had a south-facing main building, three storeys high at the front, with dining-hall and kitchens in a wing at the centre rear, and long, narrow wings to each side. Utility blocks at the rear included a bakehouse, laundry and boiler house.

In 1877, Shoreditch joined with Hackney to form the Brentwood School District who bought the school site and added further buildings. The School District was dissolved in March 1885 and the school was then taken over by the Hackney Union with further enlargements being made at the north. The site location and layout in 1915 are shown below:

Shoreditch Brentwood School site, 1915.

Shoreditch Brentwood School from the south-east, 1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The site later became St Faith's Hospital but has now been completely redeveloped as office accommodation.

Harold Court School

Shoreditch also placed children at the Harold Court School situated on Church Road in Harold Wood, between Brentwood and Romford in Essex. Harold Court was built in 1868 as a mansion house for Mr W.R. Preston, a wealthy Brentwood solicitor. He became bankrupt in 1882 and the house was taken over by the Brentwood School District of which Shoreditch was a member.

After the School District was dissolved in 1885, Shoreditch temporarily continued to use Harold Court for 120 of its children, with a further 150 to 200 being placed at the Strand Union schools at Edmonton and at the St George's-in-the-East school at Plashet.

Harold Court, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Harold Court continued in use as a children's home until 1889. It was then converted for use as a lunatic asylum and, in 1919, it was converted into a tuberculosis hospital. The hospital closed in 1958 and in 1960 the site became a teacher training college. It is now private flats.

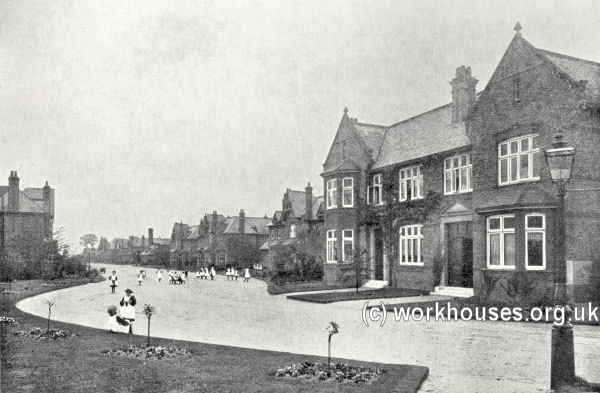

Hornchurch Cottage Homes

In May 1885, Shoreditch began to plan a replacement school for its pauper children. It decided to adopt a cottage homes scheme which would provide accommodation in a 'village' of small houses in a rural location. In 1886, it paid £6,300 for an 80-acre site at Hornchurch in Essex. The scheme, designed by Francis J Smith, was finally approved in July 1887 and the building contract agreed for £48,340. When the homes opened two years later, the final cost of the buildings and fittings was £55,639. A further £10,230 was spent on additions and alterations between 1893 and 1895.

The scheme, which was organised in the style of a village 'street', included eleven detached two-storey cottages, each of which housed 30 children, and a probationary lodge with 14 beds. There were separate schools for boys, girls and infants, a swimming bath, band room, stores, needle-room, workshops, and infirmary.

Shoreditch Hornchurch cottage homes site, 1920.

The T-shaped entrance block at the north of the site contained a two-storey lodge at its centre, flanked by boys' and girls' probationary wards where new arrivals were kept for two weeks under the charge of the porter and his wife.

Hornchurch Homes entrance block from the north, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Just inside the entrance was the Superintendent's house, which also contained the Guardians' committee room.

Hornchurch Homes superintendent's house from the north-east, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes superintendent's house from the south-east, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes from the north, 1896.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Six of the cottages housed boys, and five were for girls, each of which had its own dining room, recreation room, kitchen scullery, paved playground, offices and garden plots. The girls' cottages were under the control of a house-mother, and those of the boys under that of married couples, the husband in such cases being employed as an industrial trainer. The elder girls assisted in cooking the meals and, with the help of a laundress, did the washing for each cottage. The boys also helped with the domestic work in their own houses.

Hornchurch Homes children's houses from the north-east, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

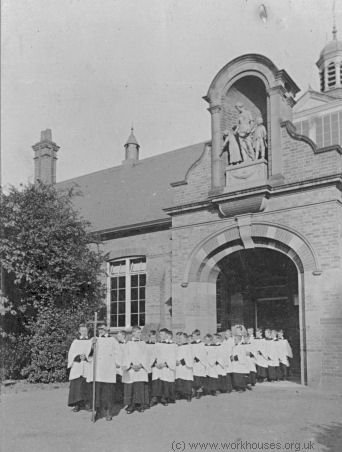

The school, located at the centre of the cottages, contained six rooms — three for boys, two for girls and one for infants. The largest of the boys' schoolrooms was used for religious services.

Hornchurch Homes school block from the west, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes school block and houses from the south-west, c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes, c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes, c.1910

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes choir boys, c.1909

© Peter Higginbotham.

Hornchurch Homes school, c.1909

© Peter Higginbotham.

The building opposite the school, now demolished, may have contained the swimming bath, workshops etc. The swimming pool was boarded over in winter to create an indoor gymnasium. The school had a gravelled open-air gymnasium and playing fields for football and cricket.

Boys were given industrial training in the engineer's, carpenter's, painter's tailor's and shoemaker's shops, and in the bakehouse and gardens. The school had its own band, through which some boys were able to join the services as military bandsmen. Those not taking up employment in a trade were placed out with the help of the organisation Homes for Working Boys in London. The girls were trained for entry into domestic service, some attending technical classes in the neighbourhood in cookery and domestic economy. On entering service, they came under the care of M.A.B.Y.S. (the Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants).

The infirmary, now also demolished, lay at the south of the site. The main building contained four dormitories and two day rooms. A covered way at the rear led to the infectious block which contained four dormitories with four beds in each. In October, 1895, two further 20-bed infirmary cottages were erected at the extreme south of the street for the reception of ophthalmic cases, ringworm, eczema and other skin diseases, direct from the workhouse.

|

In 1919, following the sudden death of his father, seven-year-old East-ender Charles Burgess and his sister were placed in the Hornchurch cottage homes. His recollections from that time provide an amazingly detailed portrait of life in the homes. (more...) |

Children's Receiving Home

By the early 1900s, Shoreditch had established a Receiving Home (also referred to as its Branch School) for up to 77 children at 26-28 Lower Clapton Road, Clapton. The home processed children coming into the parish's care, including a medical examination. Children could then be passed onto the Hornchurch Homes or other accommodation. The home also provided accommodation for the children of 'ins-and-outs' — those receiving frequent but short-term relief from the union.

Lower Clapton Road branch school, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Wood Green Branch Workhouse

In 1899, the Guardians began housing elderly male paupers in a property known as The Mansion, on Alexandra Park Road, Wood Green. The site was purchased by the Guardians in 1901. It appears to have ceased use at the end of 1909.

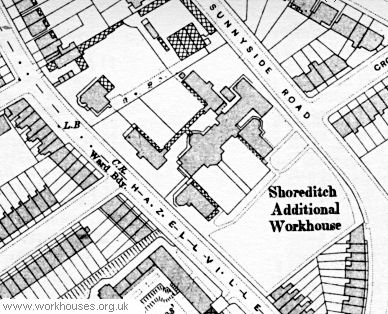

Hornsey Additional Workhouse

From around 1906, Shoreditch operated an additional workhouse on Hazellville Road in Hornsey. The site had previously been the home of the Alexandra Orphanage, erected in 1868-9 to a design by Messrs. WG Habershon and Pite at a cost of around £15,000. The design comprised four cottage blocks arranged around a central service building which contained a dining-hall, school and laundry. The site location and layout are shown on the 1913 map below.

Shoreditch Hornsey workhouse site, 1913.

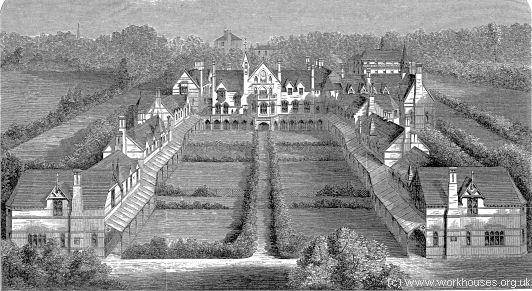

An architect's drawing of the time included additional cottage blocks to the south of the site which were never erected.

Alexandra Orphanage (architect's impression) from the south-east, 1868.

During the First World War, the building served as King Albert's Hospital, providing treatment for wounded Belgian refugees. It appears to have ceased use as a workhouse in about 1922.

Staff

- 1881 Census

- Hornchurch Homes.

- 1898 — Superintendent and Matron: Mrs and Mrs James Cowley; Chaplain Rev. WR Morris; Medical Officer: Mr AW Wallis.

- 1914 — Superintendent: Hobart A Steed; Matron Mrs Elizabeth Steed; Chaplain: Rev. Herbert John Dale; Medical Officer: Eric Alfred Wright.

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

Holdings: Guardians' minute books (1867-1930).

- Kingsland Road Workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1863-1905); Births (1862-72, 1887-91); Creed register (1869-1923); etc.

- Infirmary, Hoxton Street: Admissions and discharges (1872-88, 1891-94, 1901-2); Creed registers (1875-1905); Deaths registers (1872-85); Registers of inmates (1869-1912).

- Hornsey Lane Additional Workhouse: Creed register (1906-15).

- Brentwood School: Pauper children list (1855-76); Creed register (1869-76); Deaths register (1856-77).

- Hornchurch Cottage Homes: Admission and discharge registers (1889-1931); Creed register (1889-1931); Lists of pauper children (1889-1931).

- Harold Court School: Creed registers (1882-9); Deaths register (1886-9).

- Branch School, Lower Clapton Road: Creed registers (1899-1916).

-

St Bartholomew's Archives & Museum, West Smithfield, London EC1A 7BE.

- Kingsland Road Workhouse: Admissions and discharges (1921-37); Male patients register (1912-17); Female patients register (1912-27); Male lunatics register (1898-1910, 1915-26); Female lunatics register (1906-25); Creed registers (1907-8, 1910-34); Births (1892-1938); Baptisms (1891-1940); Deaths (1885-1969).

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Workhouses of London and the South East (2019)

- Miele, C. Hoxton: architecture and history over five centuries (The Hackney Society, 1993)

- The Lancet, July 29, 1865.

Links

Acknowledgment

- Thanks to Peter Cracknell for material on the Enfield School.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.