Charity Refuges and Hostels

A separate page gives the history of poor laws relating to vagrants, tramps, and the "casual poor", together with their treatment in the much despised workhouse casual ward or "spike". However, from around 1820, particularly in large cities such as London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool, an increasing variety of alternative forms of accommodation became available for the destitute. These were often provided by religious or philanthropic organisation and, unlike the casual ward, these establishments did not demand a stint of hard labour in return for bread and a bed.

The Liverpool Night Asylum

One of the earliest charitably run shelters for the destitute was the Liverpool Night Asylum which operated on a temporary basis during the winters of 1816, 1820-22, and 1829, before becoming a permanent establishment on Freemason's Row in 1830. In its first full year of operation, a total of 33,165 "berths" were provided and 6,122 persons were admitted, with each lodger staying an average of 5-6 nights. Of the total berths, 11,230 were used by seamen, 15,391 by mechanics and labourers, 3,876 by women, 1,328 by boys, 776 by girls, and 564 by young children. By the end of 1838, over 120,000 berths had been provided. Further details of the Liverpool Night Asylum are provided on a separate page.

Homeless seamen in London were catered for by the Sailor's Home and the Destitute Sailor's Asylum which were located near to one another in Whitechapel.

The Sailors' Home, Whitechapel

In 1829, an inaugural meeting was held with a view to setting up a charitably run lodging house for London's merchant seaman. Money was raised through subscriptions for the scheme whose object was:

The foundation stone of the Sailors' Home (also known as the Brunswick Maritime Establishment) was laid on 10th June 1830 at 4 Well Street, Whitechapel. Work proceeded slowly and the establishment finally opened in 1835. The premises and the care provided for residents were in many respects a prototype for the model lodging houses that followed.

According to the an 1852 account:

The Sailors' Home is, in the main, a boarding-house for the sailors connected with the port of London during the intervals between voyages. Sailors here obtain food, lodging, and a certain amount of washing, at fourteen shillings a week, or two shillings a day — a charge too little to pay the expenses of the house, part of which is therefore disbursed by a set of benevolent contributors. The great object is to keep the poor sailor out of the besetting temptations of the district, and to accommodate him in such a way as to sustain his bodily and moral health, and at the same time preserve his money for purposes useful to himself. On the second floor, the central part of which forms one spacious room, containing on one side a range of tables somewhat like those of a coffee-room, where newspapers, literary periodicals, and books of either an innocently amusing or an useful kind are placed for the service of those who may be disposed to spend their spare hours in reading, besides a few draughtboards for those who may choose a lighter way of passing their time. In the centre of the room are the tables at which the inmates take their meals, which are four in number — namely, breakfast, dinner, tea, and supper. Beer is allowed at some of these meals, but, excepting this particular, the house is conducted on the principles of the Temperance Societies — not a drop of spirituous liquor being ever allowed to enter it on any pretext whatever. The two wings of the building on this and the ground-floors, together with the centre of the floor above, form in all six sleeping-galleries, passing across the length of the house, and fitted up with cabins or small chambers, in the manner of the galleries at Greenwich, Chelsea, and some other hospitals. Each cabin contains a bed for one person, and affords, besides, sufficient space in which to keep the inmate's chest, and any other things he may have in his possession, for the protection of all of which by day he is furnished with a key to his door. The six galleries contain in all 200 sleeping-berths: one of them is called the City of London, and the other the City of Edinburgh Gallery, the funds for fitting them up having been supplied from those capitals respectively. Every forenoon, each of the cabins, and the whole of the galleries, and all the other parts of the house, are thoroughly washed: the Sailors' Home has consequently a remarkably clean and wholesome appearance. I could have only wished that the means of a constant ventilation were added to the other excellent arrangements. Sailors, among their other prejudices, have one against open doors and windows.

The chief patrons of the institution are persons of marked piety, and hence one of its leading aims is to cultivate the religious feelings of the sailors. Prayers are read twice a day, and there is a regular service every Wednesday evening. Religious books are also presented to the attention of the men, and they are encouraged to be regular attenders of the neighbouring floating chapel. At the same time, care is taken not to render the subject so prominent as to have the effect of repelling from the walls those who unfortunately feel a repugnance to religious exercises.

All the other interests of the sailors are promoted with the utmost zeal. In the very first place, a far greater amount of comfort is given than the charges will pay for ; so that the sailor may really be said to have a bounty put upon his accepting the shelter of this house. Secondly, all his property, of whatever kind, is received and carefully kept. The managers will take almost any trouble in order to preserve the property of the sailors from being dissipated or injured. Their money is kept on a banking principle, and most exactly accounted for. The sailor does not need to pay for any articles he purchases: he has only to go to certain reputable tradesmen who arrange with the directors to supply articles at certain fixed rates; he gets what he wants, and the tradesman is paid by the accountant from the man's funds in his hands. The inmates are thus insured against being ever cheated of a single farthing in any of their dealings out of doors. Every reasonable persuasive is used to prevent the men from drawing money for improper purposes, and to induce them to save it as a provision for the future. For this end, there is a savings' bank connected with the establishment. When sailors land from a voyage, they do not immediately receive their wages. They may, nevertheless, come to this Home, and not only receive present support upon credit, but draw to a certain small amount in anticipation of the payment of their arrears. When these are to be paid, the agents of the institution will, if they please, attend to receive the money. The accountant will also take the trouble of remitting any part of it to friends at a distance. When, again, the sailor is to depart on a voyage, and, as generally happens, receives a bill for the two first months' wages to make his outfit, the same officer receives this bill and discounts it. The institution also keeps a register of the servitude of seamen, to which they or their families may subsequently refer, when in quest of relief from any source where they may have a claim for it. In short, the trouble taken for the sake of the inmates of this house is immense and most complicated.

Nearly 3000 men take advantage of the Sailors' Home in the course of a year, the usual number of inmates at one time being from 100 to 150. After a careful inspection of its accommodations, and inquiry into its management, it appears most admirably calculated for the objects it professes, and is conducted in every particular on conscientious and benevolent principles. It is of great consequence to impress this fact on sailors, for they are so accustomed to be preyed upon, that they may well have a difficulty in believing that any persons whom they never saw before really mean them well.

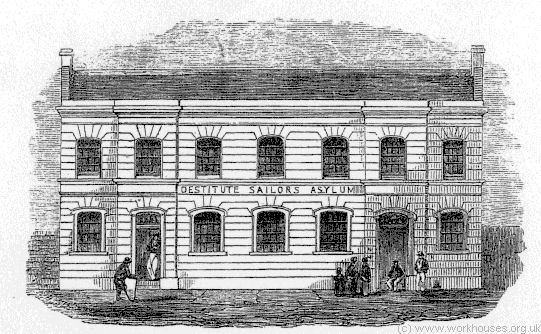

The Destitute Sailors' Asylum

The Destitute Sailors' Asylum began life on 8th January 1828 in a former warehouse in Dock Street, Whitechapel, which was leased for six years at £25 per annum. The premises were converted for the accommodation of 120 out of work seamen, a figure which reached 160 on occasion. The lower floor was used as a mess room with long tables, chairs and , at its centre, a large copper fro cooking. The steward had a cabin in one corner. The upper floor was used as a dormitory, with a separate cabin for the assistant manager. The floor was covered with a thick layer of straw, with large canvas cloths for sheets, and canvas bolsters stuffed with straw for pillows.

The daily routine began at 5 a.m. with a breakfast of "bergue" and biscuit, followed by morning prayers and the reading of two chapters of the Bible. The men were expected be out during the day looking for work, until the doors re-opened at 6 p.m. Supper, consisting of beef soup, bouilli, and biscuit, was followed by a service and address from one of sixteen ministers of different denominations who preached at the Asylum. Swearing or improper language were strictly forbidden.

By 1830, more than 3,000 seamen had passed through the establishment, many having been given clothing, bibles, and prayer-books. An association was formed with the Grampus Hospital Ship at Deptford to provide medical treatment for the Asylum's inmates and for the Asylum to receive convalescing patients from the ship.

In 1835, new permanent premises were opened on an adjacent site at 10 Well Street, designed by Henry Roberts who was to become an influential architect in the field of working-class housing.

According to an 1852 account, the Asylum was:

Destitute Sailors' Asylum, c.1850.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Other Sailors' Homes

On 28th July, 1849, a Sailors' Home was opened in Dublin by te Lord Lieutentant. Within seven months, 101 seamen were lodged and boarded there, while 44 were provided with ships, and 43 shipwrecked seamen received shelter until they could be forwarded to their own homes.

On 25th April, 1851, a Sailors' Home was opened at Portsmouth. Some of its accommodation was used by men that had been discharged from the Haslar Navy Hospital.

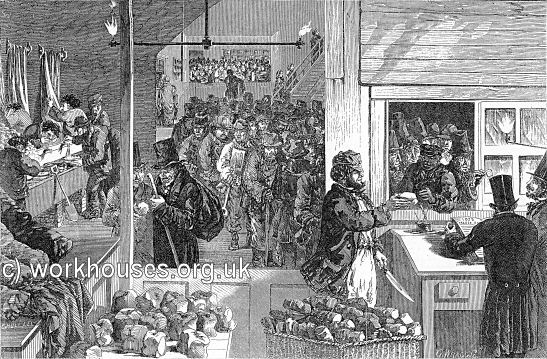

The Houseless Poor Society

The Houseless Poor Society was founded in 1819 to provide warmth, food and shelter for London's homeless and destitute during winter. The Society set up a number of "asylums" — ones for men at 6 Banner Street E.C. and 55 Warner Place, Hackney Road N.E., and ones for women at 21 Nutford Place W., at 3 Queen Street, Edgware Road, and at 39 Homer Street, W. Inmates worked towards cost of their maintenance.

Institution for the Houseless Poor admissions room, 1858.

© Peter Higginbotham.

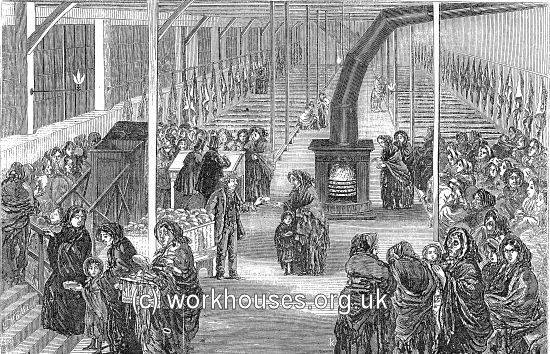

Institution for the Houseless Poor women's dormitory, 1858.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Houseless Poor Society's establishments were later taken over by the Church Army, a church mission founded in 1882 by Carlile Wilson. The Church Army's Social Department aimed to "raise the hopeless outcasts of society by labour, rescue and lodging homes" of which there were nearly 120 in London and the provinces, together with a farm colony at Hempstead in Essex. By the early 1900s it dealt with about 400,000 cases of men, women and boys are dealt with a year. In 1909, the Church Army acquired the former Yorkshire Stingo Brewery site on Marylebone Road. The building was converted into a labour home, later known as the men's Central Welfare Hostel, which provided dormitories, workshops, and a home for first offenders.

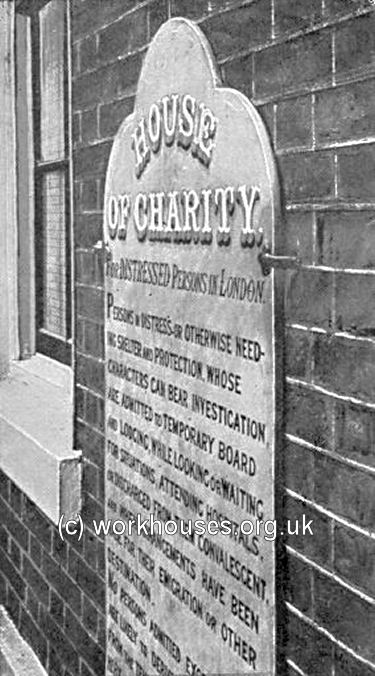

The House of Charity

The House of Charity at 1 Greek Street was another of London's early hostels for the homeless poor. It was set up in 1862 in a house at 1 Greek Street by an organisation, also called The House of Charity, founded in 1846. A distinguished group of Anglicans was involved running the house, including future Prime Minister W.E. Gladstone, and Dr Henry Munro of the Bethlehem Hospital ("Bedlam"). The group also acquired the nearby former Soho parish workhouse at 9 Manette Street (then Rose Street).

House of Charity, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

House of Charity, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The House of Charity, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The House of Charity, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The House of Charity, now known as the House of St. Barnabas-in-Soho, still continues to offer "care, support and a temporary home for homeless women".

The Providence Row Night Refuge

The Providence Row Night Refuge for "Deserving Men, Women and Children", and familiarly known as "The Dormitory", was a Roman Catholic institution established in 1860 by the Rev. Dr. Daniel Gilbert. It moved its premises to Crispin Street in 1868. It was supported by many eminent names including the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Norfolk, the Duke of Cambridge, the Earl of Denbigh, the Lord Mayor of London, and Richard D'Oyly Carte, founder of the company that put on the Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.

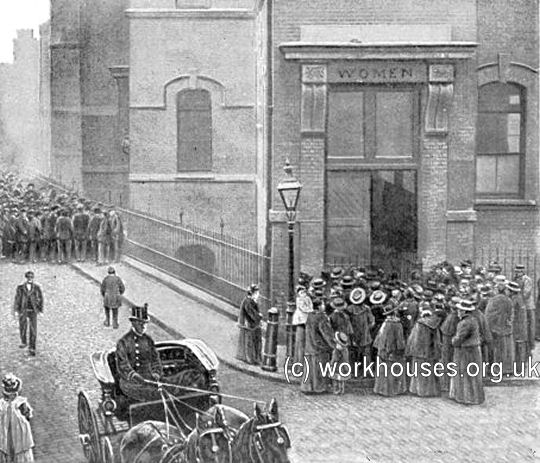

Male and female applicants at Providence Row Night Refuge, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Refuge, which could accommodate about three hundred men, women and children, operated from November to May, opening each day at 5 p.m. and usually being full fifteen minutes later. By 1900, its accommodation included sitting rooms, well-fitted lavatories, and a large footbath which could be used by a dozen inmates simultaneously. Inmates were provided with bread and cocoa each night and morning, and a meat dinner was given to those in residence on Sundays. Inmates could stay for up to three weeks — the longest allowed by any other establishment of its type. Only those who could supply the name of a referee who could vouch for their character and — in theory at least — no vagrants, tramps or professional beggars were to be admitted.

The property was later used as a convent but has now (2006) been converted to a student accommodation building known as Lilian Knowles House.

Providence Row Night Refuge, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Providence Row Night Refuge, 2006.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Ham Yard Hospice

From the 1880s, the Ham Yard Hospice, also known as the Leicester Square Refuge, off Windmill Street, took in men, particularly "travelling tradesmen" arriving in London from outside the capital. Those considered suitable were given two weeks board and lodging while they searched for permanent work. The facilities included a soup kitchen.

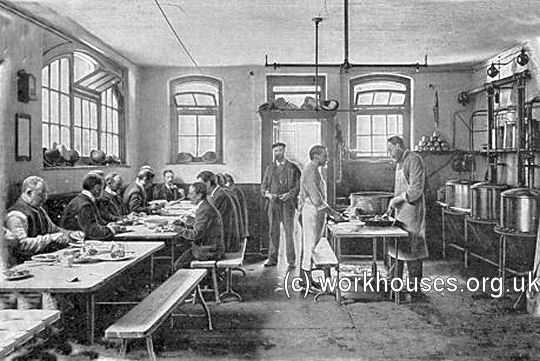

Ham Yard Hospice soup kitchen, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Field Lane Refuge

The Field Lane Refuge, at the north side of Vine Street in Clerkenwell, accommodated up to thirty-five men. The daily routine there consisted of a simple breakfast followed by prayers at 9 a.m. After a morning searching for work, a meat-soup and bread dinner was provided at midday. After more job-hunting in the afternoon, there was an evening meal of bread and meat at 5 p.m. The men contributed the household chores such as cleaning the dormitories. Evening meetings were organised in a large communal room which as also the venue of a Ragged Church service on Sundays.

Field Lane — cocoa being dispensed after Ragged Church service, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Medland Hall

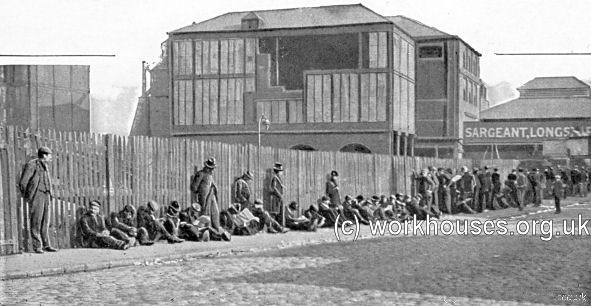

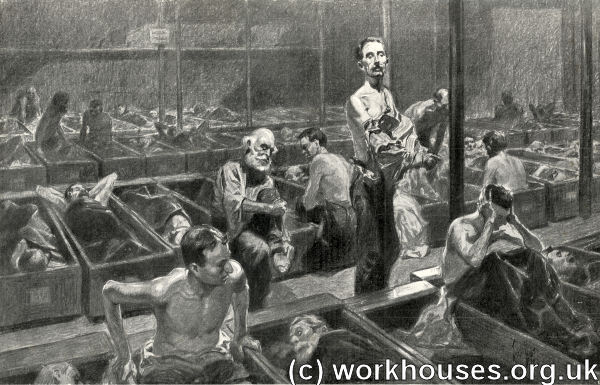

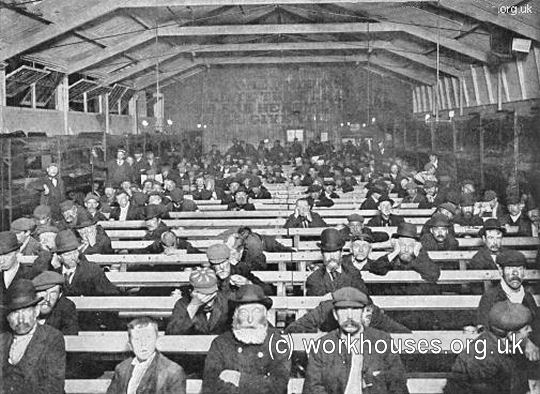

Medland Hall, on Medland Street in Ratcliff, was opened in 1893 in a hall owned by the London Congregational Union. Originally, it opened at 11 p.m. and inmates — sometimes numbering over six hundred — were allowed to stay until 6 a.m. the next morning. By the early 1900s, it was offering accommodation for a week at a time and attracted men of all nationalities. The opening time was now 6 p.m. and by mid-afternoon a long queue would be starting to form along the east side of Horseferry Branch Road to Commercial Road. By 7 o'clock, its 450 bunks would have been allocated. These coffin-like boxes contained a bed of dried sea-weed enclosed in American leather.

Medland Hall — applicants waiting for admission, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Medland Hall interior, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Medland Hall interior, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Salvation Army

In 1865, William Booth founded the Christian Mission which was reorganised and renamed in 1878 as the Salvation Army — affectionately known as the "Sally Ann". In May 1884, the Army inaugurated a "social scheme" with the opening of a women's refuge at 212 Hanbury Street in Whitechapel as part of its efforts to rescue young women from prostitution. A women's shelter opened at 194 Hanbury Street in 1889. In 1901, 'the Nest', a home for sexually abused girls, was opened on Springfield, in Clapton, London.

In 1890 William Booth published his book In Darkest England and the Way Out which documented the appalling conditions in which the poor lived. Following the success of this book, the Army began to up a wide variety of social care establishments both in London and in many other towns and cities in Britain and around the world.

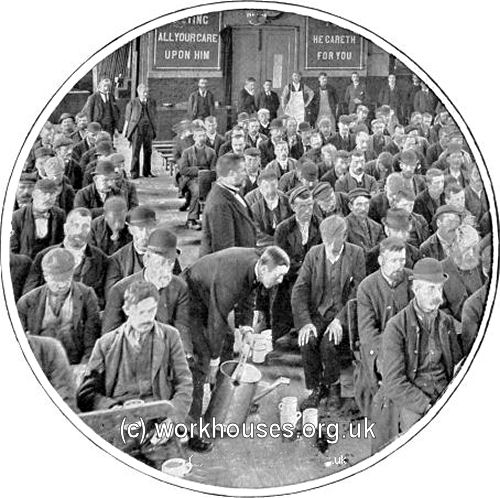

These included night shelters, lodging houses or 'metropoles'; cheap food depots; labour factories known as 'Elevators' where the destitute could earn shelter through work; workshops for unemployed carpenters and tradesmen; farm colonies; inebriates homes; and so on. Many made their first acquaintance with the Army at its Blackfriars shelter which offered down and outs a free breakfast in return for attendance at an Army church service.

Queuing for the free breakfast service, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

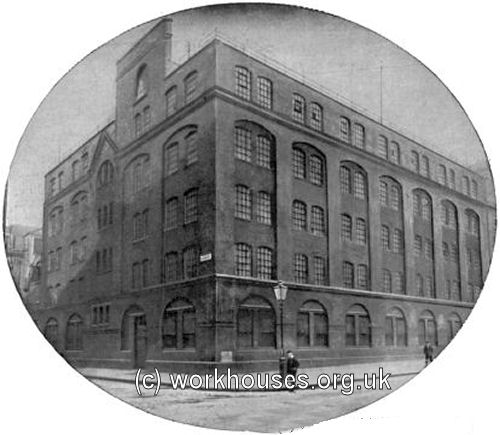

In 1909, to try and deal with the large numbers of men who were sleeping rough in London particularly on the Embankment, the Army took over a large former factory building on Great Peter Street in Westminster where 1,200 men were fed nightly.

The Great Peter Street Shelter, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A separate page gives further information on the Salvation Army.

The Penny Sit-up and Twopenny Hangover

The "Penny Sit-up" offered a space on a bench or on the floor in which the night could be spent sitting up, or leaning against a wall. In the early 1890s, the Salvation Army operated a number of such establishments, such as the one at Blackfriars, pictured below.

The Penny Sit-up at Blackfriars, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1910, the Rev. George Z Edwards, a vicar form Southport in Lancashire, went undercover to visit Preston's version of the Penny Sit-up:

When you enter some are eating their bit of food; but remember, there is no stove, no warmth, no fire here, only a (washing) boiler in the yard, where you may get hot water. There are no cooking utensils; every man carries his own drum under his coat behind his back—just an old tin of some sort with a wire handle. When your food is eaten there is nothing to do but lie down on your length of the floor, some six feet by two feet, and then if your limbs ache with lying down on the hard boards sit up, and if you are privileged to have one of the select spots against the wall, you can lean against that if you will. If you are wet through you sit or lie in your wet rags till they dry, that is all!

Think of it! Ten, twelve, fourteen hours thus. Thirty to sixty men thus, night by night, in misery, wretchedness, filth of body, and starvation. The conversation is in the dull, hopeless undertone of exhausted men, except when it flashes forth now and again in the tone of revenge, hatred and bitterness against us who have condemned them to this. It is always heavily laden with oath or blasphemy, and is of begging, pinching, roguery, trickery, beastiality, at the best of the criminal courts, their prisoners and judges. The leaden weight of exhaustion and despair is only lifted when a man is dead drunk.

But a vermin-infested room, bare of aught but men's bodies clad in rags—bodies which are not washed or groomed or cleaned from one twelvemonth to another, except when forced to go to casual ward or gaol. Bodies which are half-starved, emaciated, lean. Bodies which carry the germs of horrible disease, yet which are untended, uncared for. Bodies which, because they are so poor, so poor in rich life blood, are thereby fit and proper food for the tramp's, the dirty beggar's worst enemy, lice. Little crawling, clinging, biting lice, which breed in twenty-four hours in the scams of your clothes next your skin, and live upon you—biting, biting, feeding, feeding, like the gnawing worm of hell.

The atmosphere! Figuratively speaking, you could cut it with a knife! You yourself sleep next to an old decrepit man, who cannot always control his bodily actions; his trousers stink, stink; you will carry the stench in your nostrils for a week. Sixty thus, and if not quite thus, all unwashed, all with the smell of the unwashed. Add to this, rank tobacco smoke of all blends, some unknown even to connoisseurs, such as "kerb-stone twist" (old chews), old cigar ends, "o.p.s." (other people's stumps), and old dried tea leaves. Add to this foul breath, some very foul, add also the stale atmosphere of the room itself when empty, and remember scarce any ventilation during the night except the occasional opening of the door into the yard, and you may think you imagine what you never will, till you experience it.

By the 1920s, the Penny Sit-up had become the "Twopenny Hangover" as described in George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London published in 1933:

Bibliography

- Booth, William (1890) In Darkest England and the Way Out (London: Salvation Army)

- London, Jack (1903) The People of the Abyss

- Mayhew, Henry (1851) London Labour and the London Poor (Vol 1)

- Rose, Lionel (1988) Rogues and Vagabonds (London: Routledge)

Links

- None.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.