St Marylebone, Middlesex, London

Up to 1834

The first St Marylebone parish workhouse began operation in 1730. It was set up in the wake of Knatchbull's Act of 1723 which empowered parishes to build or rent premises for use as poorhouses, and to refuse poor relief to those refusing to enter them. St Marylebone's initially rented a property for the purpose of accommodating infants and their nurses.

In 1731, the Earl of Oxford bequeathed the parish some land on the south side of Paddington Street for use as a burial ground and for the erection of almshouses and a workhouse. Financial problems were to delay the implementation of this project for another twenty years, and from 1736, the parish's paupers were 'farmed' by a contractor at a weekly rate of two shillings a head. They were housed in the former 'Golden Lion' alehouse in Marylebone Passage.

Construction of a new permanent workhouse finally got underway in 1750 and it came into use in 1752. It stood opposite the southern end of Northumberland Street (now Luxborough Street) at the north-east corner of the burial ground. Accommodating about forty inmates, it initially continued to be run on 'farming' principles. The first Master, Francis Parent, provided the inmates' board, taught the children reading, writing and arithmetic, and set both adults and children to work in spinning and winding silk. For this he received 1s.6d. a head per week, and any income from the inmates' work. Within a year, however, Parent was dismissed as a result of his drunkenness, frequent absences, misappropriation of supplies, and the discovery of one of his sons in bed with a female inmate. Succeeding incumbents of the post were employed on the more straightforward basis of an annual salary of twenty pounds.

With the rapid urbanization of the area in the 1760s, the size of the new building soon proved inadequate. It also became infested with rats from sewers under the adjacent burial ground. By 1772, 220 inmates were occupying accommodation designed for 40. Two extra storeys were added to the building and the former 'Neptune' public house was hired as accommodation for the sick. Even these measures proved inadequate, and in 1774 the Vestry proposed the construction of a large new workhouse. They approached the major local land-owner, the Duke of Portland, to help find a site and were offered land on the north side of Paddington Street, running the length of Northumberland Street up to the recently laid out Marylebone Road.

The building and operation of the new workhouse required a special Act of Parliament, passed in 1775. The parish's poor law administration was to be conducted by a body styled the Directors and Guardians of the Poor, which included thirty parishioners appointed by the parish Vestry. Construction of the new building began later that year and was completed by the following spring when just under 300 inmates were transferred from the old building. The new building, designed by Alexander Allen, himself a local Guardian of the Poor, was designed to accommodate up to a thousand inmates and cost £18,770. Its two-storey design included a main block running north-south along Northumberland Street, with separate blocks at each end running east-west. In 1786, a chapel was added at the west, to complete a quadrangle.

The old workhouse continued in use for a while as an infirmary, but its size and location led to periodic fever outbreaks such as one in 1791, in which the matron and apothecary died. In 1792, a new infirmary block accommodating 300 was built at the north-west of the main workhouse site. The old building was then demolished.

St Marylebone workhouse site, 1793.

St Marylebone 1792 infirmary with rest of workhouse behind.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1793, Britain's war with France led to a widespread increase in pauperism. Even with its much increased capacity, the new workhouse soon became full, reaching 1,168 inmates by 1797. Reluctantly, the Guardians had to resort to providing out-relief without demanding entry into the workhouse.

As well as adult paupers and their families, the workhouse also took in foundlings. Babies were also abandoned on its doorstep. In 1815, an infant was left with a note attached:

I am little Kitty, my parents are poor.

I crave your pity, now I am left at your door.

I do not despair but a hope I do cherish

I shall be taken care of, as I am left to the parish.

In earlier years, foundlings were apparently often given a name based on where they were found, for example "Cavendish Square"!

The workhouse buildings gradually expanded. The infirmary was enlarged in 1825, and a new boy's school was added in 1827. In 1841, a new 200-bed women's dormitory was added, followed in 1843 by a block for 50 able-bodied men to the rear of the chapel. The workhouse capacity was then 1449 , plus 300 patients in the infirmary.

Another way to relieve the pressure on numbers in the workhouse came through the emigration of younger inmates to new lives overseas. Early one morning in June 1832, a party of 24 long-standing female residents of the St Marylebone workhouse set out for Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) under a voluntary emigration scheme. It was reported that they were all robust healthy-looking young women, cleanly and suitably apparelled, between 16 and 25 years of age, and, except at the trying moment of departure, seeming in full and buoyant spirit. All had been given a substantial breakfast after being allowed to sleep the previous night in the same ward. Friends and relatives gathered at the workhouse door to make their often tearful farewells with force sometimes being required to separate mothers from their offspring. The party were conveyed in two omnibuses to St. Catharine's Docks, from where they travelled by steamer to board the Renown at Gravesend, accompanied thus far by the workhouse governor, two matrons and other officers. The cost to the parish of the whole proceedings was said to be more than £300. In fact, the Renown landed in October 1832 at Sydney where her cargo was discharged and the 'free' girls brought ashore. According to local newspaper reports, they were first lodged in a lumber yard and within a day or so, the girls were 'placed in respectable servitudes'.

After 1834

Because of its status as a 'Local Act' parish, St Marylebone was largely exempt from the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, and little co-operation was shown to the new Poor Law Commissioners. For example, following a further Poor Law Act in 1844, the Commissioners grouped unions and parishes into districts to provide 'district asylums', or casual wards, for vagrants. St Marylebone, together with several other parishes, refused to participate in the scheme and it was eventually abandoned.

In response to the increase in vagrancy, two 'Nightly Asylums' (one for men and one for women) were opened in February, 1846. These admitted vagrants for one night only. On entry, vagrants were searched to ensure they had no money, then bathed and disinfected. For supper and breakfast they were given 8 oz. of bread and a pint of soup or gruel. The Asylums were closed the following year after an outbreak of fever.

At the end of 1846, pressure on the main workhouse was at an all-time high, fuelled to a large part by the famine in Ireland, and a change in the settlement laws which granted settlement after five years residence. St Marylebone had a considerable Irish community who could now claim relief without fear of repatriation as would have previously been the case. After reaching a peak of 2,264 when every corner of the workhouse was turned over to accommodation, the population levelled off at just under 2,000.

As numbers rose, so did the cost of providing for them, and severe economies were introduced. Remuneration to inmates employed in the workhouse was cut. Nurses and laundrywomen now received 1s. per week, the inmates who taught handwriting in the girls' school and who laid out the dead received 1s.6d, and the cook and barber received 2s. These reductions were calculated to save £500 a year. A proposal to abolish the inmates' Christmas pudding was rejected, however, although portions were to be limited to 8oz. and raisins substituted for currants.

Further conflict with the Poor Law Board (the successor body to the Poor Law Commissioners) ensued in 1856 after allegations that several young female inmates had been beaten by workhouse staff including the Master, Richard Ryan. The Directors and Guardians initially refused to do more than reprimand those involved. However, pressure from the Poor Law Board eventually led to Ryan's departure, an event celebrated in a street-ballad entitled The women flogger's lament of Marylebone workhouse! (Bodleian Library, Firth c.16(317))

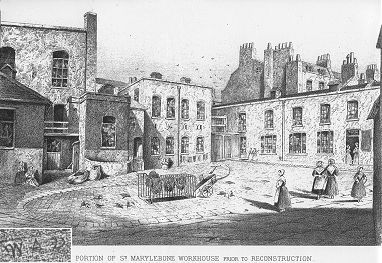

St Marylebone workhouse engraved by an inmate "W.A.D.", 1866.

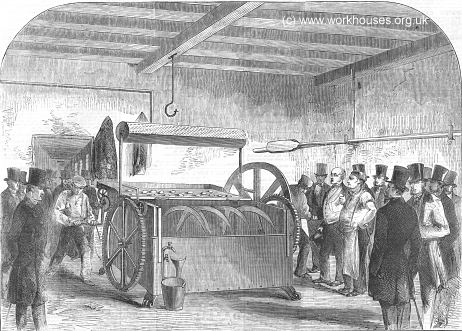

In 1858, the workhouse hosted the trial of a new invention — Stevens's bread-making machine — which claimed to make dough more efficiently and hygienically than by using manual labour.

St Marylebone bread-making trial, 1858.

In 1865-66, the medical journal The Lancet published a series of detailed reports into the conditions at a number of London workhouse infirmaries. Its report on the St Marylebone workhouse raised a number of criticisms. The buildings were said to be old and badly organised and in need of replacement. The duties assigned to the medical officer were impossibly heavy and he needed at least three resident medical assistants. You can read the full text of the Lancet report.

In 1867, the workhouse played a part in a local disaster. On 15th January 1867, the workhouse Master, George Edward Douglas, was walking with his wife (who was also the Matron) in Regent's Park when ice on the frozen lake gave way and 200 skaters fell into the freezing water. Douglas immediately organized the transport of survivors back to the workhouse for medical attention. Forty recovered bodies were also taken to the workhouse.

A major change in administration occurred later in 1867 when the Metropolitan Poor Act empowered the Poor Law Board to bring all local Act parishes within the scope of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. Thus, on the 2nd August 1867, the Directors and Guardians of the Poor of the parish of St Marylebone were abolished and were replaced by an elected Board of Guardians, independent of the parish Vestry.

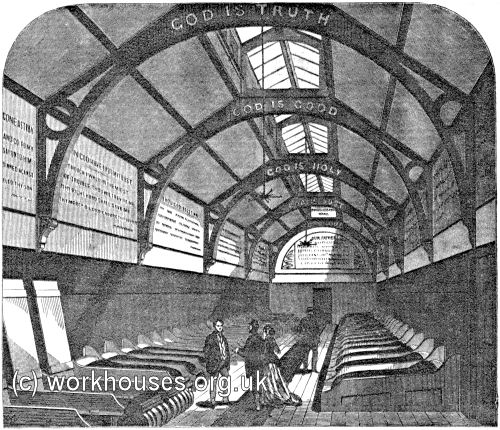

Beginning in 1867, a series of major building works began. New temporary casual wards, designed by H Saxon Snell, were opened at the north-east corner of the site. These had an open layout and were adorned by scriptural texts printed in large red letters on their blue walls. The Illustrated London News printed an article on the event.

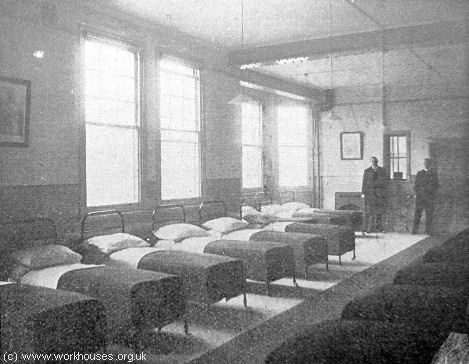

St Marylebone workhouse casual ward, 1867.

The Marylebone Workhouse being in every respect a good example to the other London workhouses, we give an illustration of the new building in connection with it, which was opened last week for the accommodation of tramps or casual poor; about 11,000 of whom, men, women, and children obtained relief in the last six winter months. They are washed with plenty of hot and cold water and soap, and receive six ounces of bread and a pint of gruel for supper; after which, their clothes being taken to be cleaned and fumigated, they are furnished with warm woollen I night-shirts and sent to bed. Prayers are read by Scripture-readers; strict order and silence are maintained all night in the dormitory; and the "Amateur Casual" would find nothing to complain of. The bed consists of a mattress stuffed with coir, a flock pillow, and a pair of rugs, At six o'clock in the morning in summer, and at seven in winter, they are aroused and ordered to work. The women are set to clean the wards, or to pick oakum; the men to break stones, but none are detained longer than four hours after their breakfast which is of the same kind and quantity as their supper. Their clothes, disinfected and freed of vermin, being restored to them in the morning, those who choose to mend their ragged garments are supplied with needles, thread, and patches of cloth for that purpose. If any are ill, the medical officer of the workhouse attends to them; if too ill to travel, they are admitted into the infirmary. A board of Good Samaritans could do no more.

The new building, designed and constructed by the architect, Mr. H. Saxon Snell, of Chancery-lane, is situated at the back of the old relief offices, adjoining the Marylebone Road.

The entrance is through the passage leading to the relief offices. At the end of this passage is a general waiting-room, with another for females only, next to which is the female bath-room. The bath-room is 12ft. long, 9ft. wide, 18ft. high. There are two baths, made of Stourbridge clay, having a white glazed surface. The water is heated by a stove in the same room, under the management of the attendant, the cistern holding a hundred gallons of hot water for the two baths. Adjoining this bathroom is the female sleeping-ward, 58ft. long, 18ft. wide, 15ft. high to the lowest part of the sloping edge of the roof, and 22ft. high to the apex. The roof is supported on circular cast-iron ribs, bolted to iron stancheons in the thickness of the walls on solid stone bases. Running along the whole length of the room is a ventilator 5ft. wide. The sides of the ventilator open and close; the top, being glazed, affords light. On the floor immediately beneath is a cast-iron grating covering a brick air-channel which is supplied with fresh air from the outside by covered channels under the floors. It also contains the hot-water pipes for heating the apartment in cold weather. The room is well lighted at night by two pendent star-burners. The arrangements for heating, ventilating, and lighting are entirely out of the reach of the inmates. Ranged down each side of the apartment are the sleeping-bunks for forty- four women and twenty children. These bunks are generally 6 ft. 6 in, long and 2 ft. 4 in. wide, but some are made wider to afford accommodation for a woman and two children each, The bunks consist of a white deal board, supported on each side by a deal partition which rises high enough to prevent the intermingling of the breaths of the occupants of two adjoining berths, though not so high as to prevent the officials in attendance from seeing each person from any portion of the room. The boards forming the beds are so hung on pivots as to be capable of being turned up every day for the purpose of cleaning the floor beneath. The head of the bed under the pillow is slightly raised, and hinged separately, for the purpose of lifting and depositing the clothes of the sleeper; the clothes of each inmate being thus under her own protection. The head of each bed is six inches from the wall, and a current of air is always free to pass under the bed and upwards towards the ventilators. One feature in this ward is the Scripture texts, the Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments, printed on the walls and ceiling, in red letters on a blue ground.

The arrangements for the accommodation of the males are identical with that described for the females, except that the bath-room stove is so modified as to allow the smoke and heat to pass by an iron flue through an adjacent disinfecting chamber. If on examination it be found requisite, the clothes of the casual are, whether male or female, hung up in this heated chamber, and well fumigated with sulphur.

On each side of the main building are ranged the working sheds, where the casual in the morning picks oakum or performs such other tasks as may be assigned to him. These sheds are about 12ft. wide and 9ft. high, and are well lighted and ventilated by skylights.

The total cost of the building, including the payment of the architect's commission, has not exceeded £1800.

Further developments included a new board-room and offices for the Board of Guardians, and female aged and infirm wards along Northumberland Street at the east of the workhouse site. The new infirm wards were the subject of a report in The Builder in May, 1868.

SOME new wards have been erected for the purpose of relieving the over-crowded state of the house, and providing more suitable accommodation for that class of persons to whom only a workhouse should be made attractive. The Guardians of St. Marylebone are anxious that their aged poor should be made as comfortable as the rules of a workhouse will permit.

The building is erected at the south-east angle of the workhouse ground, and occupies the site of the old bakehouse and laundry.

The wards, six in number, are each 40 ft. wide, 60 ft. long, and 13 ft. high, and give 780 cubic feet of air space to each occupant. The beds are ranged down either side of the room, and a double row of beds occupies the centre of the room, which is divided longitudinally by a partition 5 ft. 6 in. high. The western ends of the rooms are formed as large double bay windows, and constitute the day rooms. The skirting at the back of the beds forms a box 9 in. square, with a perforated zinc front ; below these boxes are channels containing hot-water pipes ; at the ends of these channels, and in the front and back walls, are large openings through which, by raising a damper, is admitted the external air. By this means the fresh air will be first warmed by passing over the hot-water pipes, and then rising upwards be emitted through the perforated front of the skirting boxes into the wards immediately under the beds. The foul air is carried off through wide channels in the ceilings, which communicate with large flues running up the side walls, and terminating just above the level of the eaves of the roof ; each opening into a flue is provided with a door that is under the control of the nurses only.

The upper wards are somewhat differently constructed from those of the lower wards, inasmuch as the ceilings follow the line of the sloping sides of the roof, which are supported at intervals on semi-elliptic cast-iron ribs. The emission of foul air in these wards is provided for by a channel in the apex of the ceiling, running the whole length of the room, and has zinc flues at intervals open to the air.

The walls are plastered throughout, the lower portion being finished with Portland cement; they are coloured with varied and pleasing tints, which give them an appearance as cheerful and homely as they are unlike the bare, lime-washed, vault-like brickwork of an ordinary workhouse ward. The basement of the building contains store-rooms, heating-furnaces, coal stores, and other offices.

The total cost of the building as finished for occupation, including every description of fitting, gas-lighting, architect's commission, and all other contingencies, was about 6,400l. ; and this being for the accommodation of 240 inmates, is at the rate of 27l. per bed.

The architect is Mr H. Saxon Snell ; Messrs. Manley & Rogers are the builders ; Messrs. Potter & Sons executed the heating, ventilating, and sanitary works ; and Messrs. Abercrombie the gas-lighting apparatus.

The recently added casual wards, offices and "chronic" wards, can be seen on the 1870 map below.

St Marylebone workhouse site, 1870.

On 4th November 1878, a new three-storey casuals' block, providing individual cells, was opened to the west of the site, replacing the temporary one put up in 1867. It was kept separate from the rest of the workhouse with its entrance variously referred to as being on York Place, David Street (now Porter Street), or 86 East Street (now 82 Chiltern Street). Unlike the temporary casual ward of 1867, the block included a separate cell for each inmate.

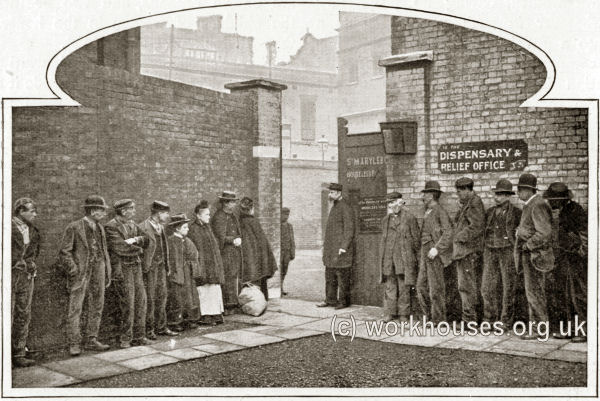

St Marylebone casual ward entrance, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A dispensary and outdoor relief office were also erected on an adjacent plot of land between East Street and York Court. The East Street frontage of the dispensary is now the only surviving remnant of the workhouse buildings.

Former St Marylebone Dispensary, East Street (now Chiltern Street).

© Peter Higginbotham.

A new block for 240 able-bodied females was added at the south-west of the site in 1888. The workhouse population at this time was usually around 1,600. The site layout in 1894 is shown below.

St Marylebone workhouse site, 1894.

St Marylebone dining hall, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone men's yard, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A major phase of new building took place in 1897-1901. This comprised two five-storey blocks for aged and infirm males at the north fronting onto Marylebone Road, a two-storey block for able-bodied men at the west of the site, and a new central administrative block at the east on Northumberland Road. The administrative block also contained the main chapel, and included the demolished building's clock, bells, and foundation stone inscribed 'ST. MARYLEBONE WORKHOUSE FOR THE POOR BEING LAME IMPOTENT OLD AND BLIND ERECTED IN THE YEAR MDCCLXXV'. During the building work, 400 inmates were temporarily accommodated at the disused Holborn workhouse building on Grays Inn Road. The new buildings took the workhouse's capacity to 1,921.

St Marylebone workhouse from Marylelone Road, 1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone new workhouse entrance, 1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone new workhouse dormitory, 1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone women's ward, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone casuals' entrance, c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Amongst the new facilities was state-of-the-art kitchen. One observer described it as:

The construction quality of the new buildings was soon to cause concern as shown by this press report from May, 1900:

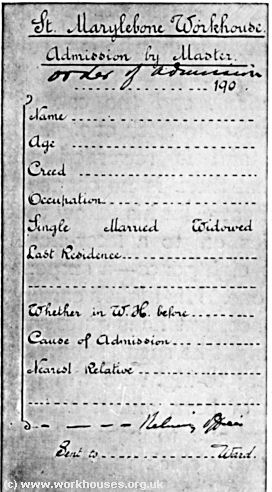

St Marylebone workhouse admission ticket, c.1901.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In the early 1900s, the collector of English folk songs, Cecil Sharp, used workhouse inmates and casuals as one of the sources for his material. One of these (name unknown) was photographed at St Marylebone.

Cecil Sharp's Marylebone Man

© English Folk Dance and Song Society.

In 1914-15 the casual ward block housed Belgian war refugees, then from 1918-21 was used as military detention barracks. During the First World War the main workhouse also took paupers from the Paddington, Hampstead, Hammersmith and Lewisham unions, whose own workhouses had been taken over for military purposes.

After 1930, the workhouse became the St Marylebone Institution, and its inmates gradually became the elderly and infirm. During the Second World War, parts of the Marylebone Road Blocks were used as a recreation centre for civil defence workers, then after the war as a transit centre for displaced persons from the Continent. In 1949, the institution was renamed Luxborough Lodge and was overseen by a 'Warden' rather than a 'Master'.

The former workhouse finally closed on January 6th, 1965, and its inmates were dispersed to accommodation elsewhere. The buildings were then demolished and replaced by flats and accommodation for the London Polytechnic.

Rackham Street Infirmary

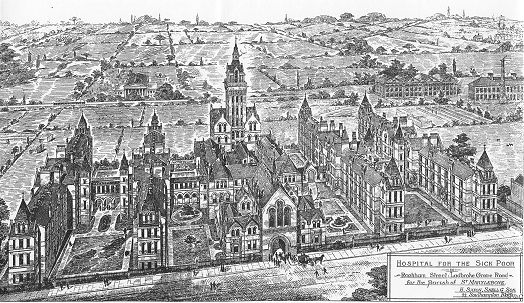

On July 7th, 1879, the foundation stone was laid for a new union infirmary at Rackham Street, Ladbroke Grove. The buildings, which would accommodate 744 sick poor, were again designed by Henry Saxon Snell and son who received a congratulatory letter from Florence Nightingale. This move also freed up much needed space at the main workhouse. The site location and layout are shown on the 1888 map below:

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary site, 1888.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary from the south, 1881.

© Peter Higginbotham.

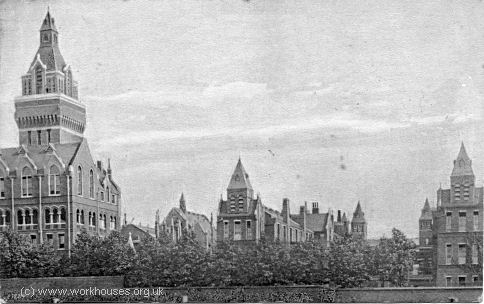

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary from the north-west, c.1907.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary from the south-east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

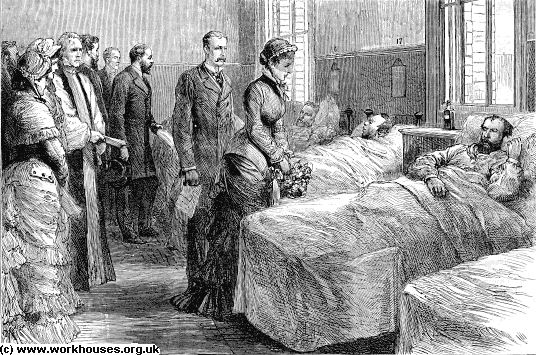

The new building was opened on 29th June 1881 by The Prince and Princess of Wales.

Prince & Princess of Wales visit St Marylebone Infirmary, 1881.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A few months before the opening, a report had been published of a visit to the site by the Architectural Association. This is reproduced below illustrated with modern views of the buildings.

On Saturday last a visit was paid by some members of the Architectural Association to an extensive series of buildings now approaching completion in Rackham-street, Ladbroke-grove road, Notting-hill (or "North Kensington," as it is sometimes called), for the Board of Guardians of the parish of St. Marylebone. These buildings have been specially designed by the architects, Messrs. H. Saxon Snell & Son, as an infirmary for the sick and infirm poor of that parish, and have been erected by Messrs. Wall, Bros., of Kentish-town, the contract amounting to 109,000l. The site acquired is three acres and a half in extent. The buildings consist of an administrative block in the centre, flanked on either side by two double ward blocks parallel to each other and to the central block, so that, including the central or administrative block, the main buildings Consist of five blocks parallel to each other. The buildings are planned on what is now well known as the pavilion principle, so that each block of buildings is, as far as is compatible with facility of communication and administration, isolated from other portions of the building. The entrance is in Rackham-street, on the south side of the site, through a spacious gate-way, over which is the chapel, 60 ft. long by 30 ft. wide, with boarded wagon-roof of trefoil section, 22 ft. high to the wall-plate, and about 45 ft. to apex. Sittings are provided for 250 persons. The interior walls and tracery of the windows are very nicely executed in white Suffolk bricks. The chapel is warmed by means of one of Mr. Saxon Snell's patent "Thermhydric " stoves, which are also used in the wards, as hereafter mentioned. Flanking the entrance gateway and chapel are residences for the medical officers.

St Marylebone Rackham Street entrance and chapel, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary ward block, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary ward block and walkways, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary administrative block, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Rackham Street infirmary children's ward, 1920s.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The infirmary buildings have now been listed and have recently been refurbished, offering a variety of medical services under the name of the St Charles Centre for Health and Well-being.

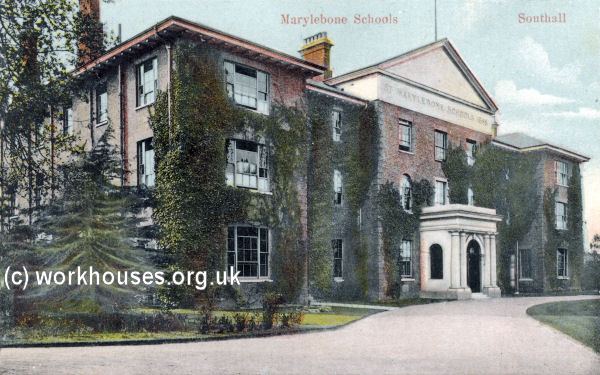

St Marylebone School, Southall

As early as 1849, proposals were being considered to provide a separate school outside the workhouse. For a mixture of legal reasons, and problems in finding a suitable site, these plans did not progress until 1858 when a site was purchased at the west side of South Road in Southall at a cost of £2,000 including farm buildings. By 1860, a large school had been erected which, including furniture, cost a further £14,500. The buildings were expanded in stages and additional land purchased in 1883 taking the site to 15 acres of which more than four acres were covered in buildings and yards. In 1901, a new infirmary, probationary and receiving cottages were erected at the north-east of the site. The school was enclosed by a ring fence and surrounded by fields, gardens and orchards. The site location and layout are shown on the 1894 map below

St Marylebone Southall school site, 1894.

The main building was three storeys high, ranged around three sides of a square, at the rear of which were grouped the dining-hall, kitchen and bakery. A single-storey 35-bed infirmary lay to the rear and other detached blocks contained a laundry, swimming baths, workshops etc. The children slept in dormitories each averaging 40 beds in size. The accommodation also included a nursery and a kindergarten with (in 1898) a trained Froebel teacher. The school could accommodate up to 390 children in total, although actual numbers were usually between 300 and 320. Children were examined by the medical officer each week.

St Marylebone Schools, Southall, c.1908.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone Schools prize-giving, Southall, c.20.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Boys were giving training to be engineers, carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, gardeners or bakers. The girls were taught needlework, and in the last three months of their time at the school before entering domestic service, six of the elder girls were placed in the training home, "Avenue Lodge" and given a thorough training in household duties. For recreation, cricket and football were popular with both boys and girls. Some of the elder girls also cultivated small plots of ground. Service was held in the main hall on Sunday afternoons; for other services, the children went to the local parish church. The children wore uniforms and all their clothes, except for the boys' suits, were made in the school.

In 1916, the school was taken over by the Australian Forces as a military hospital.

The Southall school buildings had been demolished by 1933. The site is now occupied by Hambrough primary school.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

-

The

Ancestry UK

website has two collections of London workhouse records (both name searchable):

- Westminster workhouse records are available on FindMyPast, .

-

London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- Workhouse holdings include: Births (1866-1930); Deaths (1855-1914); Creed registers (1868-1930); Guardians' minute books (1867-1930); Financial records (1832-1930); Staff records (1857-1932); etc.

- Rackham Street Hospital holdings: Admissions and discharges (1891-1943); Deaths (1884-1934).

- Southall Schools — Admission and discharge registers (1864-1916); Creed registers (1869-1916); Deaths registers (1860-99).

Bibliography

- Neate, Alan R The St Marylebone Workhouse and Institution, 1730-1965. St Marylebone Society, 1967. Revised 2003 edition available, price £6.00, from St Marylebone Society Publications, 33, Linhope Street, London NW1 6HU or via the St Marylebone Society website.

- The Builder, May 2nd, 1868, p.323

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.