Inside the Workhouse

Workhouses varied enormously in size, with the smallest such as Belford in Northumberland housing fifty inmates, while the largest such as Liverpool could be home for several thousand. However, all workhouses were essentially a self-contained — and often largely self-supporting — community. Apart from the basic rooms such as a dining-hall for eating, day-rooms for the elderly, and dormitories for sleeping, workhouses often had their own bakery, laundry, tailor's and shoe-maker's, vegetable gardens and orchards, and even a piggery for rearing pigs. There would also be school-rooms, workshops, nurseries, infirmary and fever wards for the sick, a chapel, and a dead-room or mortuary. Workhouses were also highly compartmentalised to separate the various classes of inmates, with the yards between the various buildings being divided up by eight-foot-high walls.

You can get a good idea of the complexity of a workhouse from old maps or plans. You can see examples of these on some of the pages for individual institutions such as Manchester or Oxford. For more detail on the different styles and layouts of workhouse buildings, see the architecture section. The workhouse tour section of the web-site will also show you what many of the buildings actually looked like.

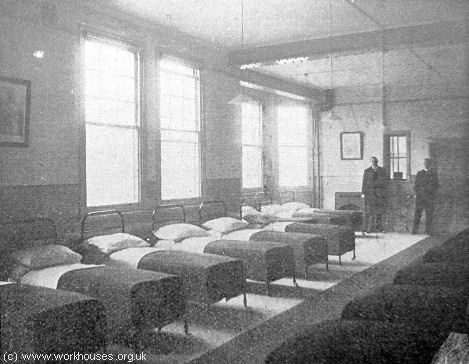

Once inside the workhouse, an inmate's only possessions were effectively their uniform and their dormitory bed. Beds were simply constructed with an wooden or iron frame, and could be as little as two feet across. The mattress, in the 1830s and 1840s at least, was typically a palliasse filled with flock (tufts of waste wool/cotton) or straw. Inmates were usually provided with sheets, blankets (two over and one underneath the sleeper, a coverlet and a pillow. Bed-sharing, particularly amongst children, was common although it became prohibited for adult paupers.

Early iron beds from Gressenhall workhouse.

© Peter Higginbotham.

St Marylebone workhouse dormitory, 1900.

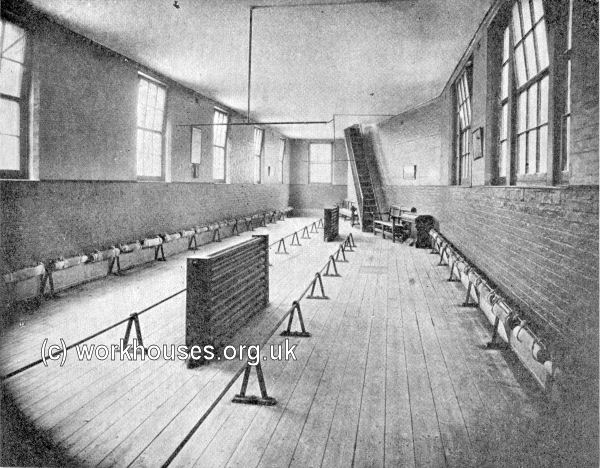

For vagrants and casuals, the 'bed' could be a wooden box rather like a coffin, or even just be a raised wooden platform, or the bare floor. In some places, metal rails provided a support for low-slung hammocks.

Casuals ward at Whitechapel workhouse c.1900.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Irish workhouses were particularly cramped, with the narrow attic space pressed into service as sleeping space for children as shown here at Londonderry.

Londonderry attic ward.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The inmates' toilet facilities were often a simple privy — a cess-pit with a simple cover having a hole in it on which to sit — shared perhaps by as many as 100 inmates. Dormitories were usually provided with chamber pots, or a communal 'tub'. After 1860, some workhouses experimented with earth closets — boxes containing dry soil which could afterwards be used as fertiliser. They were mostly used by rural workhouses where there was a ready supply of soil and there the spent soil could be usefully disposed of.

Once a week, the inmates were bathed (usually superintended — another assault on their dignity) and the men shaved.

St Marylebone women's day room, c.1902.

© Peter Higginbotham.

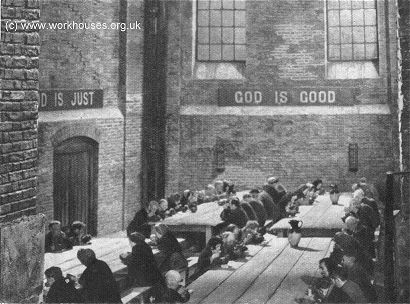

Meals were usually eaten in a large communal dining-hall which often doubled-up as a chapel. Some dining-halls had religious mottoes on the wall, reminding inmates that they should be grateful for the care they were being given.

Workhouse dining hall

© Peter Higginbotham

The addition of separate chapels, often funded by charitable contributions, became more common from the 1860s onwards. As elsewhere in the workhouse, men and women were segregated. The chapel at the Tonbridge workhouse had separate entrances for men and women.

Tonbridge chapel from the east, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Tonbridge chapel interior, 2001.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.