Pauper Emigration under the New Poor law

The organised emigration of poor children dates back to a least 1619, when the London Common Council despatched 100 vagrant children to join the first permanent English settlement in North America, Jamestown in Virginia. A further party was sent in 1620, and more followed in 1622 to join the reinforcements sent following the Indian Massacre of the settlers in Virginia. From the mid-1600s, the demand for labour in Britain's colonies led to the illegal emigration of hundreds of children through their "spiriting", or kidnapping, a practice particularly associated with Scotland. This ended in 1757 after a number of Aberdeen businessmen and magistrates were exposed for their involvement in the trade.

In 1833, the year before the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act, the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners (CLEC) were set up to manage the programme of emigration to Britain's colonies (Canada, Australia, New Zealand etc.). Under the new regime, some emigrants could qualify for a free passage if they were under forty, capable of labour, of good character, having been vaccinated against smallpox, and from occupations such as agricultural labourers, shepherds, or female domestic and farm servants. Young married couples, preferably without children were viewed as the ideal candidates. Assisted passages were also available with less stringent restrictions to healthy able-bodied labourers whose moral character could be vouched for. Workhouse inmates, however, or those in regular receipt of parish relief, were explicitly excluded from the CLEC schemes.

Provision for the emigration of the poor, with the cost being borne by an emigrant's home parish, was however included in section 62 of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act:

This channel of emigration was overseen by the Poor Law Commissioners (PLC). The PLC, with a few exceptions, would sanction the emigration of any of its poor that a parish was prepared to fund. Those categories who were not acceptable included the wives and children of transported convicts, of soldiers, or of men who had deserted them and then gone overseas.

All such parish-funded emigration had to have the PLC's direct approval. The responsibility for conducting and managing individual emigration arrangements was, however, in the hands of the Board of Guardians for the union of which the parish was a member.

In their first annual report, in 1835, the Commissioners noted the modest uptake of the Act's provision with a total of 320 persons having emigrated from 80 parishes, mostly to Canada. However, a year later things were looking rather different with 5,241 persons having been funded to move. Almost three quarters of the total were from Norfolk and Suffolk, with 250 emigrants from a single parish — Banham in Norfolk. The total numbers emigrating from each county in the year from June 1835 to July 1836 are shown in the table below. As before, the large majority had Canada as their destination.

| County | Parishes | Emigrants | Cost (£) |

| Bedford | 2 | 18 | 215 |

| Buckingham | 1 | 25 | 100 |

| Berkshire | 1 | 30 | 150 |

| Cambridge | 3 | 39 | 201 |

| Huntingdon | 2 | 27 | 200 |

| Kent | 18 | 320 | 1823 |

| Lincoln | 1 | 17 | 100 |

| Middlesex | 1 | 88 | 860 |

| Northampton | 2 | 23 | 135 |

| Norfolk | 91 | 3068 | 15198 |

| Oxford | 2 | 11 | 40 |

| Somerset | 2 | 11 | 50 |

| Southampton | 11 | 182 | 1068 |

| Sussex | 17 | 248 | 2032 |

| Suffolk | 32 | 787 | 4198 |

| Wiltshire | 5 | 347 | 2042 |

| TOTAL | 191 | 5241 | 28412 |

In the following year, ending July 1837, the total fell to 1,112 — a figure which was rarely again exceeded. The chart below shows the annual number of poor-law emigrants from England and Wales from 1835 to 1899 by which time the overall total of emigrants had reached 36,000.

Annual Emigration under Poor Law 1835-1899..

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1842, just over 1,000 poor-rate funded individuals emigrated, compared with more than 128,000 emigrating under the CLEC schemes. Nonetheless, in 1843, Member of Parliament Charles Buller claimed that Britain's emigration policy was one of "shovelling out paupers to where they may die without shocking their betters with the sight or sound of their last agony".

By the mid-1840s, the destinations to which the PLC were prepared to support emigration to "some British colony, not lying between the tropics". In practice, the list of eligible destinations comprised: Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, The Cape of Good Hope, New South Wales, South Australia, West Australia, Van Dieman's Land (Tasmania), and New Zealand. Destinations to which emigration was prohibited by the PLC included India, the West Indies, Singapore, the Western Coast of Africa, and the United States of America. Apart from a presumably patriotic disinclination to send British labourers to the USA, the PLC argued that they had much less influence over the treatment that emigrants might receive than would be the case in Empire countries.

The relative popularity of Canada and Australia as destinations for emigration went up and down. The Canadian cities of Quebec and Montreal offered a much shorter voyage than to Australia. However, emigration to Canada came to a halt in the winter months when St Lawrence River was frozen. South Australia, which was proclaimed a colony in 1836, operated a free passage scheme until the spring of 1841. It was then suspended due to lack of funds until 1847, when various assisted emigration schemes were offered. The discovery of gold or diamond deposits could also boost a country's popularity.

Workhouse Orphans

In 1848, the CLEC made a concession in its bar against candidates for emigration who were in receipt of poor relief. A new drive was launched to encourage emigration to South Australia and New South Wales, which it was hoped would amount to 10,000 individuals from Britain and 4,000 from Ireland. It was proposed that orphans between the ages of fourteen and eighteen, who were of industrious habits and good character, free from all disease, and having been vaccinated against smallpox should be considered for emigration. They would also be required to have a sufficient knowledge of reading, writing, and arithmetic, and the principles of the Christian religion. Orphanhood was defined as having lost at least one parent. Female orphans were much preferred as candidates for emigration because males greatly outnumbered females in the population of these colonies.

A CLEC memorandum outlined some of the features of the proposed scheme which would convey emigrants from Plymouth to either Sydney or Port Philip.

Besides the money wages, labourers in the country are generally provided with a dwelling, and the following allowance of provisions by their employers : 10 lbs. of meat, 10 1bs. of flour, 1½ lb. of sugar, and 3 oz. of tea per week.

The voyage to these colonies generally occupies about 100 days; and during that time the emigrants will be fed according to the annexed scale, at the public expense, subject, of course to future modifications; if experience should show them to be for the benefit of the emigrants.

The males and females are intended to be conveyed in separate ships. Teachers will bo appointed to them, and means will be taken to provide for the instruction of the emigrants in conformity with their respective creeds. The books furnished to the vessels will consist exclusively of those authorized by the National Board of Education. In those of the ships which may carry orphans (females) there will bo a trustworthy Matron to take charge of the emigrants, under the direction of the Surgeon, who will be intrusted with the general management of every ship.

The emigrants' ships will be despatched every month during the present year froth Plymouth, to which place the emigrants must be conveyed at the expense of the Board of Guardians. Emigrant ships can be despatched from Plymouth only, because it is only at Plymouth (with the exception of London,) that the Commissioners have an Emigrant Depot which will enable them to collect the emigrants previous to embarkation, and officers under their control, who can ascertain by inspection that the emigrants are all in a fit state of health to embark, that their persons are clean, and their clothes clean and sufficient. The calamities which would result from the introduction of any infectious or contagious complaints on board one of those vessels, render this arrangement indispensable.

It will be necessary that each emigrant should be provided with the following articles which compose the lowest outfit that can be admitted: —

For Males.—Six shirts; six pair of stockings; two pair of shoes; two complete suits of exterior clothing, one of which must be made of some warm material.

For Females.—Six shifts; two flannel petticoats; six pair stockings; two pair shoes; two gowns, one of which must be made of some warm material.

As a general rule, it may be stated, that the more abundant the stock of clothing, the better for health and comfort during the voyage. At whatever season of the year it may be made, the emigrants have to pass through very hot and very cold weather, and should therefore be prepared for both.

Every pains will be taken to find the emigrants respectable employers; when their age and circumstances render it fitting, they will be bound apprentices, under laws which are in force in the colonies. It will be stipulated that fair wages shall be paid by the employers, according to the current rate prevailing in the district; and after deducting such portion as may be required to pay for clothes, and other current expenses, the remainder of their wages will be reserved, to be given to them at the expiration of the contract, or, in case of females, at their marriage, provided it be approved of by the Government, or by the committee appointed to act on its behalf. A power will be retained of forfeiting the reserved wages of any of the children who may abscond, or whose indentures may be cancelled for misconduct.

The Board of Guardians will determine whether, in order to obtain these advantages, they will provide the outfit and conveyance to the port of embarkation on behalf of the orphans in their respective workhouses; and on their communicating their decision to do so to the Poor Law Commissioners, an officer will be deputed by the Emigration Commissioners to visit the workhouses, in order to ascertain whether they contain any suitable candidates for emigration of the above class.

Amongst other things, a daily dietary was specified for the voyage to Australia:

| Biscuit | Beef | Pork | Preserved Meat | Flour | Raisins | Suet | Peas | Rice | Preserved Potatoes | Tea | Coffee, weight when when roasted | Sugar | Butter | Water | Vinegar | Mustard | Salt | |

| lb. | lb. | lb. | lb. | lb. | oz. | oz. | Pts. | lb. | lb. | oz. | oz. | lb. | oz. | Qts. | Weekly. | |||

| Sunday | 2/3 | - | - | ½ | ¼ | 2 | 1½ | - | - | ¼ | ¼ | - | - | - | 3 | |||

| Monday | 2/3 | - | ½ | - | ¼ | - | - | 1/3 | - | - | - | ½ | ¼ | 3 | 3 | Half pint | Half oz. | Two oz. |

| Tuesday | 2/3 | ½ | - | - | ¼ | 2 | 1½ | - | ¼ | - | ¼ | - | - | - | 3 | |||

| Wednesday | 2/3 | - | ½ | - | ¼ | - | - | 1/3 | - | - | - | ½ | ¼ | - | 3 | |||

| Thursday | 2/3 | - | - | ½ | ¼ | 2 | 1½ | - | - | ¼ | ¼ | - | - | - | 3 | |||

| Friday | 2/3 | - | ½ | - | ¼ | - | - | 1/3 | - | - | - | ½ | ¼ | 3 | 3 | |||

| Saturday | 2/3 | ½ | - | - | ¼ | 2 | 1½ | - | ¼ | - | ¼ | - | - | - | 3 | |||

The workhouse orphans emigration scheme was taken up by the Poor Law Commissioners in Ireland, at a time when the great famine was just beginning to subside. The Commissioners decided, however, to confine the scheme to females. In the first year of the operation, 2,219 girls emigrated from Irish workhouses with another 1,056 the following year. The overall level of poor-law emigration from Ireland reached a high of 4,386 in 1851-2 with Quebec being the most popular destination — large parties arrived there from a number of west Ireland unions including Caherciveen (371), Clifden (340), Dingle (355), Ennistymon (376), and Kilrush (389).

Advertisement for Emigrant Ships, 1849..

© Peter Higginbotham.

Despite its enthusiatic take-up in Ireland, the CLEC's Australian scheme appears to have been rather less used in England and Wales by the newly created Poor Law Board (the successors to the Poor Law Commissioners). However, the emigration of the poor from mainland Britain was given a boost in the late 1840s by two changes in the law. First, under the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1848, the financing of emigration could be charged to a common fund within each union, rather than having to be funded by the parish in which an emigrant was settled. Second, the 1850 Poor Law Amendment Act provided that a Poor Law Union could undertake the emigration of any "poor orphan or deserted child under the age of sixteen years" that was in its care. The resulting increase in emigration peaked at a total of 3,271 in 1852 and then, as in Ireland, declined to a few hundred a year.

British Home Children

In the late 1860s, a number of British organizations and private individuals running homes for abandoned or orphaned children began to organise the emigration of parties of children to the colonies, with Canada being the most popular destination. Prominent amongst these individuals were Miss Annie Macpherson and Miss Maria Rye, both of whom organised the emigration and resettlement of several thousand children, many of whom came from workhouses. An added impetus was given to their emigration schemes in 1871 by a relaxation in the regulations and contracts that had formerly been required between Poor Law Unions and emigration agents.

Miss Rye's interest in emigration began in the early 1860s, helping educated young women emigrate to the British colonies, as a result of which she co-founded the Female Middle-Class Emigration Society. After several years of escorting parties of women and girls to Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, she turned her attention to orphan and "gutter" children, proposing their emigration to rural Canada and the western states of America. She her first party of three children to Canada in June 1869, followed, in October 1869, by a group of 75 girls aged four to twelve, including 50 from Liverpool's Kirkdale Industrial School. Miss Rye established a Canadian base in a former court-house and gaol at Niagara-on-the-Lake. The home, which she named Our Western Home, was adapted to act as a holding home for 120 children. She also acquired a large house, known as Avenue House, at the south side of Peckham High Street in London where destitute girls were housed and educated. She obtained financial support for her work from a variety of sources including donations from readers of The Times, grants from the Canadian Government, and funding the British poor law authorities.

Avenue House site, 1896. (The building no longer exists.)

In 1874, following adverse reports about the treatment received by some of the children, and suggestions she was personally profiting from the public funds she had received, an inquiry was conducted by Local Government Board Inspector Mr Andrew Doyle. Doyle visited Canada to interview around 400 children who had emigrated under Miss Rye's care and his report, published in 1875, expressed serious concerns relating to their welfare and aftercare. His report noted:

Although Doyle's findings were vigorously disputed by Miss Rye, the emigration of pauper children was halted until 1883, mainly due to the lack of adequate ongoing superintendence of the children in their new homes. Despite this setback, Miss Rye continued her activities and over a 25-year period placed around 5,000 girls in new homes in Canada. In 1895, she handed over her home and her work to the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society.

Scottish-born Annie Macpherson opened the Home of Industry at 60 Commercial Road in Spitalfield in early 1869. Like Miss Rye, she organised the emigration to Canada of poor families and children. In the spring of 1870, she escorted her first party 100 children aboard The Peruvian. The children found homes at places including Quebec City, Montreal, Toronto, and Hamilton, and other places in Ontario. Miss Macpherson established a home known as Marchmont in Belleville, Ontario, with further ones following at Galt in Ontario and at Knowlton in Quebec. The children Miss Macpherson took to Canada came via her own Home in London and also through other organisations such as Dr Barnardo's, William Quarrier's Homes in Scotland, and the Smyly Homes in Dublin, as well as some from workhouses.

Miss Macpherson and Miss Rye operated completely independently of one another. However, after the bad publicity resulting from the Doyle report, Miss Macpherson reorganised her operation, and in 1877 handed over the running of the Belleville home to her colleague Ellen Bilborough, and the Knowlton home over to her sister. By 1893, some 5,730 boys and girls had emigrated through her homes. Her organization continued in operation until 1920 when its work was taken over by the Liverpool Sheltering Home.

In April 1883, the Local Government Board agreed new measures with the Canadian Department of Agriculture in Ottowa in relation to emigrant poor law children. During the rest of that year, the Board approved the emigration to Canada of a total of 133 pauper children. In the same year, approval was given for 296 other persons of whom 95 went to Canada, 105 to Australia, 42 to the USA, 28 to New Zealand, 15 to Nova Scotia, 5 to New Brunswick, 3 to British Columbia, 2 to Cape Colony, and 1 to India.

The rules governing the emigration and inspection of poor children emigrating to Canada were revised several times and from 1888 included the following provisos:

2. The guardians on receipt of such report shall cause a copy of it to be furnished to the Local Government Board.

3. The person proposed to be entrusted by the guardians with the emigration of a child shall have notice from the guardians whether the child is a Protestant or Roman Catholic, and he shall give an undertaking if the child is a Protestant that he shall be placed with a family of the Protestant faith, or if the child is a Roman Catholic that he shall be placed in a Roman Catholic home.

4. A child before being sent to Canada shall have been under previous instruction for at least six months

(a.) In a workhouse or separate school under the guardians, or a district school; or at a public elementary school at the cost of the guardians; or

(b.) In a school certified by the Board under the 25 & 26 Vict. cap. 43. It will not be regarded as essential that such period of instruction shall immediately precede the emigration.

5. The guardians shall instruct one of their medical officers personally to examine each child proposed to be sent to Canada, and to report in writing as to its health, both of body and mind, and to certify whether, in his opinion the child is in all respects a suitable subject for emigration to that country. A copy of this report and certificate muse be forwarded to the Local Government Board.

6. The guardians must have such evidence as they deem satisfactory that the person taking out the children has a reasonable prospect of finding suitable homes for them in Canada.

The Board consider that as a general rule girls should not be sent out above the age of 10 years, and in no case, except under very special circumstances, above the age of 12 years.

Also in 1888, the Board published a guide for guardians in determining what would be a reasonable amount to pay to the persons entrusted with the children for the cost of taking them from Liverpool to homes in Canada. It noted that the charges made by the steamship companies for passages to Quebec and Halifax were £4 for adults and £2 for children under twelve. A "kit" and bedding also had to be obtained by the emigrant at a cost of a few shillings. The railway fares from Quebec to places in Ontario, where most of the homes for the children were situated, ranged from £1 to £1.15s. per adult, according to distance. Children between 5 and 12 years of age were conveyed at half fare.

There was, however, still no compulsory ongoing monitoring of children in their new homes other than a single initial inspection. This changed in 1899 when the Canadian Ministry of the Interior agreed to arrange annual inspections, provided that they were paid for in advance by the child's union or parish.

Other Emigration Agencies

Miss Rye and Miss Macpherson were not the only individuals to set up emigration schemes for Britain's poor. From the 1830s onwards, the emigration of both children and adults was organised by a growing number of independent organisations and agencies. Some of these are briefly listed below.

- The Children's Friend Society

The The Society for the Suppression of Juvenile Vagrancy (later known as the Children's Friend Society), was founded in 1830 by Captain Edward Pelham Brenton. Its object was "to reclaim and provide for vagrant children found in the streets without any means of subsistence except by begging or thieving." The Society operated the Brenton Juvenile Asylum at Hackney Wick where boys were trained in agricultural skills on its 10-acre site. A girls' home, known as the Royal Victoria Asylum was set up at Chiswick to provide girls with training to equip them for domestic service. In 1832, a lack of suitable positions led the Society to send its children overseas. destinations included the Cape of Good Hope, the Swan River Colony in Australia, Canada, and Mauritius. The Society folded in 1842 after receiving adverse press publicity about the ill-treatment of one of its children who had been sent to the Cape.

- Dr Barnardo's Homes

Dublin-born Thomas John Barnardo came to London in 1866 and the following year set up a Ragged School for the education of poor children in the East End. One evening, Jim Jarvis, a boy at the school took Barnardo around the district to him children sleeping in gutters and on roofs. As a result, Barnardo dedicated himself to alleviating the plight of destitute children and in 1870 opened his first home for boys at 18-26 Stepney Causeway. One evening, an 11-year old boy, John Somers (nicknamed "Carrots") was turned away because the shelter was full. He was found dead two days later from malnutrition and exposure and from then on the home carried the sign 'No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission'. As well as providing accommodation, training facilities were developed at the home to equip the boys to earn their own living.

Bootmaker's Shop at Stepney Causeway, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.In 1873, a Village Home for Orphan, Neglected and Destitute Girls was established at Barkingside in Essex. The site eventually grew to sixty acres and housed 1,400 girls in a cottage homes development based on "family-sized" cottages arranged around a village green.

The Barkingside Girls' Homes, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The Barkingside Girls' Homes, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.In around 1872, Barnardo began sending children to Canada through Miss Macpherson's organisation. From the early 1880s, a larger scale emigration scheme was organised after Barnardo visited Canada and was given the use of a home in Toronto, followed by another known as Hazel Brae in Peterborough, Ontario, which was mainly used for girls. Emigration was extended to New South Wales in Australia in 1921.

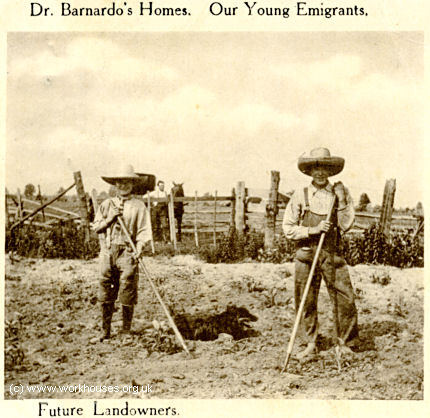

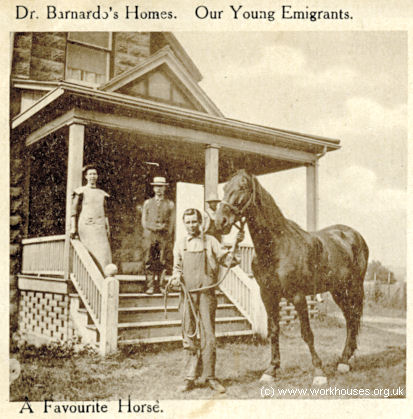

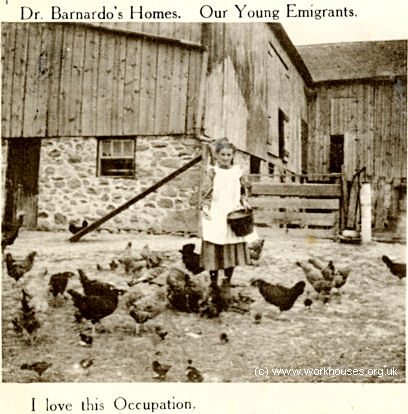

Some of Dr. Barnardo's emigrants, c.1912.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Some of Dr. Barnardo's emigrants, c.1912.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Some of Dr. Barnardo's emigrants, c.1912.

© Peter Higginbotham.- Quarrier's Homes

-

William Quarrier, born in 1829, came from a poor Greenock family. He learnt a trade as shoemaker and eventually became a successful businessman and an active Christian. Wanting to help children sleeping rough on the streets of Glasgow, in 1871 he opened a night refuge on Glasgow's Renfrew Street. He then raised funds to set up a cottage homes village for orphans at the Bridge of Weir in Renfrewshire. By the early 1890s, the Quarrier's Village accommodated over 800 children and included 34 cottages, a school, and a church.

Quarrier's Homes, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Quarrier's Homes, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.Like Barnardo's, Quarrier made use of Miss Macpherson's organisation in sending children to Canada. The first batch, in July 1872, sailed on the St. David and were initially received at the Marchmont home in Belleville, Ontario. In 1888, Quarrier set up his own home "Fairknowe" in Brockville, Ontario. Of the total of 30,000 children that passed through the Quarrier's Village, over 7,000 emigrated to Canada or Australia.

Quarrier's Homes, 2005.

© Peter Higginbotham. - The Smyly Homes

In Dublin, in about 1850, Ellen Smyly opened her first Bible school in Harmony Row, near Grand Canal Street. Destitute children were fed and given a basic education together with teaching on the Scriptures. She then opened residential homes, one for boys then one for girls, followed in 1859 by "the Bird's Nest" for infants. Eventually around a thousand children were being cared for in "The Smyly Mission Homes and Ragged Schools of Dublin".

From the early 1870s, children from the Smyly Homes were sent to Canada through Mrs. Macpherson's organisation. In 1905, the founder's daughter Miss Annie Smyly, set up a home in Hespeler, Ontario, and the first group of children to stay here arrived August 1905, on board the SS Virginian. The First World War Emigration more or less ended emigration from Ireland and in 1917 the Hespeler home was taken over by the Children's Aid Society.

- The Salvation Army

In 1865, in the East End of London, William Booth founded the Christian Revival Association which eventually became the Salvation Army in 1878. The Army became involved in a variety of social projects among the poor both in Britain and around the world. Its first involvement in emigration was in 1882, when it had been involved in finding women emigrants for Australia. Booth's 1890 book In Darkest England and the Way Out, which documented the appalling living conditions of many of London's poor, proposed the creation of an "Over-Sea Colony" where the "destitute multitudes" could be resettled. The Colony never materialised and the Army instead became involved in more conventional emigration schemes, setting up its own Emigration Board in 1894. From 1901, small batches of men from the Hadleigh Farm Colony were despatched to Canada. In 1903, a much larger programme of emigration was initiated, with almost 200 embarking in a single week in April 1904. In 1905, the Army chartered its own ship, the SS Vancouver, which sailed on 26th April to Canada with a 1,000 emigrants aboard. Many more such sailings followed on vessels that include SS Kensington, SS Southwark, and SS Ionian. In 1907, an enlarged Emigration Department was opened at 122 Queen Victoria Street.

Families leaving for Canada escorted by a band, c.1910.

© Peter Higginbotham.At the end of the First World War, to help the plight of widows and their children, the Army arranged for a total of 1,769 women and 1,019 children to emigrate to new lives in Canada, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. In the late 1920s, the Army arranged the passage of several consignments of emigrants to Australia on the Vedic. By 1938, the overall total of men, women and children settled overseas by the Emigration Department was almost 250,000.

Bibliography

- Blackburn, Geoff (1993) The Children's Friend Society: Juvenile Emigrants to Western Australia, South Africa and Canada, 1834-1842.

- Booth, W (1890) In Darkest England and the Way Out

- Coldrey, Barry (1999) Good British stock: Child and youth migration to Australia. (National Archives of Australia)

- Kohli, Marjorie (2003) Golden Bridge: Young Immigrants to Canada, 1833-1939 (Natural Heritage)

- Anna Magnusson (2006) The Quarriers Story (Birlinn)

- Parr, Joy (1980) Labouring Children (London: Croom Helm)

Links

- Databases of British Home Children in Canada

- British Home Children in Canada - a wide-ranging collection of resources

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Good British Stock: Child and youth migration to Australia

- Barnardo's

- Quarrier's Homes

- William Quarrier Home Children Association

- The Salvation Army (UK)

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.