The Imbeciles Asylum, Caterham

The Imbeciles Asylum at Caterham was one of the first institutions erected by the Metropolitan Asylums Board which had been set up in 1867 to administer care for certain categories of the sick poor in metropolitan London. The MAB's initial plans comprised new smallpox and fever hospitals at Stockwell, Homerton and Hampstead, together with asylums for imbeciles at Leavesden to serve the north of the capital and at Caterham to cover the south. Each institution has its own management committee which received nominal direction from the MAB.

The Caterham asylum was situated on the west of the Coulsdon Road to the north-west of Caterham. The 72-acre site cost £5,756 (£80 an acre) and the new buildings around £85,000.

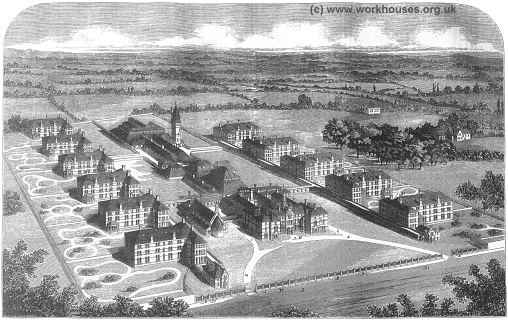

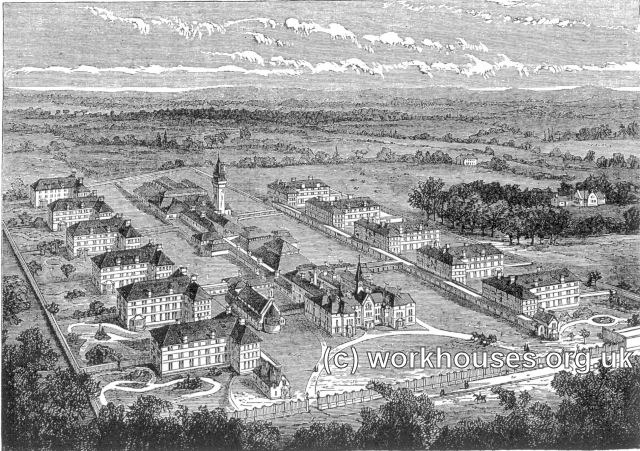

Architects' design for proposed Caterham and Leavesden Asylums, 1868

The design of the Caterham and Leavesden asylums, by Messrs. J Giles & Biven, was essentially identical, although was adapted for local differences in the two sites. Each was intended to accommodate 1,560 inmates — 860 females in six separate blocks, and for 700 males in five separate blocks.

Leavesden block plan, 1868.

On July 25th, 1868, The Builder reported the details of the plans as follows:

The small plan shows that the central administrative block extends from the south front, facing the road to a lower part of the ground northwards. The south front is occupied by the medical and official department, the centre by the stores department, the extreme north by the laundry and engineer's department, to obviate nuisance from steam and the necessarily offensive exhalations. The corridor to these buildings has a fall of about 1 in 30, to meet the natural fall of the ground, without resorting to steps.

From the central kitchen, right and left, are corridors (10 ft. wide), with the workrooms of the females and the workshops of the males each on their respective sides, occupying the space which forms the connecting link between the administrative department and the blocks on either side, and convenient of access from both. The entire width between these is 110 ft. giving space for the erection of the chapel without interfering with the free passage of air.

At right angles with this corridor, north and south, on either side, extend the corridors connecting the blocks. These are 8 ft. wide, one story high, and fireproof, both sides having windows, with tops opening, so as to admit of the free passage of air through them. By this means each block is entirely isolated. The infirmary block occupies the south end of each corridor, and next these, on either side, are placed the steward's and matron's houses. It has been thought better in each case to give a small detached house at a distance from these central offices, than apartments immediately adjoining them. Practically, these officials spend a certain number of hours each day at their business, and after that time it is thought equally convenient and more agreeable to be somewhat removed from the scenes of their duties, but within call if required by the head attendants.

There are on the female side five general blocks, each for 160, and one infirmary block for 60 patients. This gives 860. On the male side are three blocks of 160 each, and a shorter one for 110. These, with the infirmary block, give 650. This shorter block can, if required, be extended to the general size, and will accommodate 50 more.

The extreme length of the corridors from the kitchen to the most distant blocks is 180 yards on the female side and 138 on the male side.

The detached infirmary, for infectious diseases, is placed in the rear, north of all the buildings, so that the prevailing winds which blow south-west would not pass from it to the other buildings.

The chapel is placed on the left of the administrative block, rather than in front of it (as at first seemed its best position), because it is believed that a large detached chapel in front of the entrance to such a building must have a gloomy effect, and practically throw into shadow that to which it should be but an accessory.

The engineer's house is on the right, within easy reach of the boiler and engine-houses, and those parts of the building likely to require his attention. The chaplain's house is on the right of the main body of the buildings, and near the main road. Both these have private access to their houses without passing the asylum grounds.

Administrative or Central Block.

This being the great centre — the store-house — the manufactory of everything consumed by so great a number of people, it is of the highest importance to its economical working, that every apartment within it shall be neither so unnecessarily large as to cause waste in building and require extra labour and attendance, nor so small as to impede the due and proper execution of each attendant's work.

There are fireproof corridors to every part of the building ; every apartment, it is claimed, can be reached without passing through any other ; each is accessible both from the male and female sides, and all food, stores, clean linen, &c., can be obtained for their respective patients' blocks without either sex of attendants trespassing on the department of the other.

Male and female departments of attendants are separated day and night by the door across the centre corridor, and that across the corridor by the female's visiting room.

In the front and centre of the main building is what for convenience of examination we may call

The Official and Medical Department.

Here is the principal entrance-hall, on one side of which are placed the board-room, waiting-room, clerks' offices &c., and on the other the medical superintendent's residence, a house complete in itself, having bed-rooms on the floor above, in addition to the three reception-rooms, kitchen, scullery &c. On the right is the board-room with retiring-room and offices, and the apartments of the medical assistants on the floor above them. It is also near the head-attendant's offices, and the visiting rooms of both sexes.

From each side of the entrance-hall branch two corridors, one to the male, the other to the female side of the buildings, thus giving from this point a separation of sexes both as regards patients and attendants.

On the outer side of these corridors are placed the visiting rooms for patients, with separate entrance, overlooked by the head attendant's office adjoining in each case. Here commences the

Attendant's Department,

male and female, on either side. These entrances are for all the subordinate officer, as well as the visitors to patients ; thus no person can enter or leave the building without being seen by the head attendant on duty. On each side, and under the head attendant's supervision, are the staircases leading to the attendants' dormitories of each sex.

The centre of the administrative department is occupied by the general store, large enough for separation of the different kinds of stores, and with small stores leading out of it. The steward's office is in the centre. On one side is a large open court, into which all carts containing beer, flour, or stores can be taken and unloaded under the eyes of the steward and his attendants. Beyond this is the bakehouse, with scullery &c., attached, and this extends to the line formed by the intersecting corridor.

The kitchen is 50 ft. by 45 ft., by 25 ft. high, with through ventilation and light above, large enough to cook for fully 2,000 persons if necessary. The scullery adjoins the kitchen, and is 50 ft. by 25 ft., by 22 ft. high. Adjoining are the cook's larder and dairy, and a meat store is placed on the left conveniently near, in which all meat will be received and weighed before entering the kitchen to be cooked. Near these are cooks' store and kitchen servants' rooms, and, on the opposite side, a coal store for kitchen and the general daily distribution.

Outside the corridors, which enclose the kitchen, and in the north angle formed by these and the intersecting corridor leading to the patients' blocks, on the male side are work-shops, and on the female side the work-room, with the matron's offices and store, and the workmistresses' apartments and stores adjoining. Beyond these, and near the boiler house, on both sides, are the bath-houses for both sexes, each containing twelve baths, with dressing-rooms and W.C.

The Laundry Department.

The linen, conveyed by trucks from the patient's blocks, will be brought into the "receiving rooms," passed into the "washhouses" for either sex, and washed and dried either in the grounds or on the steam-horses, thence passed into the laundry, and folded, mangled, or ironed, as may be necessary. It will then be passed into the delivering-room, and there sorted and given out at the slides to trucks in the lobby.

It is calculated that about eighty female patients will be required to assist in the laundry, and, as great loss of time and inconvenience would arise if these were compelled to return to their respective blocks for their meals, a hall for dining has been placed close to the laundry, with a servants' mess-room adjoining. Close by the laundry is

The Engineer's Department.

This is kept distinct in itself, and is entered from the yard only. This position of the boiler and engine houses and their attendant workshops is, for convenience of supplying steam to the kitchen and scullery, bath-houses, laundry, machinery-room, drying horses, &c., and it will be seen that economy of heat, and necessarily fuel and labour, will be effected by its position being central between these apartments. It will also be seen that the infirmary patients' blocks of both sexes have their baths supplied from these boilers, one boiler house thus supplying the entire establishment without waste of heat. Here also is placed the water-tower, with the smoke-shaft from the boiler within it. This tower will rise to a height of 65 ft., and have a cistern at the top containing 30,000 gallons, for the supply of water in case of fire in any block or part of the building — an efficient supply until the engine could be got to act. Fire-cocks, with hose, will be fixed on the staircases of each block and at other parts of the buildings, by means of which, if kept right, any portion could be deluged with water in a few minutes.

Patients' General Blocks.

Of the blocks, which run at right angles to the intersecting corridor, all are, with the exception of the infirmary block, precisely alike.

The ground-floor of each block is a day-room for the patients, 105 ft by 36 ft. and 14 ft. high, with windows on the north side 6 ft. from the ground of the day-room, on the south side within 3 ft., and with a large bay on that side also.

The designs differ from the plan followed in modern infirmary pavilion blocks of placing all the W.C.s and lavatories at the end farthest from the connecting corridor. It is essential that the class of persons here should be, with the least possible labour to attendants, constantly watched, and this could never be the case with these places far removed from the centre of supervision.

Each of the two dormitory floors is alike, and accommodates eighty patients on a floor, divided by an iron partition and iron columns in the centre. Each division has an attendants' room, a lobby for the patients' clothes at night (it being very undesirable for these to remain in the dormitory), a linen store, and a spacious lavatory.

Each attendants' room has a window giving supervision of each division of forty patients.

The windows of the dormitories, twelve on each side, are opposite each other ; they are 3 ft. wide and 4 ft. from the floor. In all cases they come between the beds, and not over them. There are also windows at each end, giving through direct ventilation to the staircase of each block.

Infirmary Blocks.

These blocks are in each case of three floors ; each floor being in its internal arrangements alike, it being assumed that the ground floor would be occupied by the very infirm or epileptic patients, whom it would be undesirable and almost impossible to take up and down stairs. Should this not be the case, the ground floor could be used a day-room, for the sixty patients ; although beds are shown over the entire floor of the wards, the end of each might be used as a day-room for patients becoming convalescent, and separated by a screen or partition from the other portion if required.

Each ward has three fireplaces, the windows are opposite each other, and within 3 ft. of the ground, it being more cheerful for the sick to see out of them. On each of the three floors are placed rooms for excitable patients — four in number. These are approached direct from the staircase, and have a lobby between the dormitory and them, so that the noise may not annoy the sick.

With reference to ventilation and heating, all the corridors connecting the blocks have windows on both sides of their entire length, and those in the administrative block are lighted and ventilated above, and at intervals, at the sides.

Open fireplaces are employed generally throughout the buildings, and wherever gas is used it will be made the means of carrying off the vitiated air by means of galvanized iron tubes in the thickness of the floors, connected with the spare ventilating flues from the various rooms.

In order to keep up unceasing movement of the air in the upper part of the ward, the whole of the windows, twenty-four in number, in each dormitory have a portion of their height, about 2 ft, working on a swivel, so as to open to any desired inclination. The top of this swivel-light is constructed as a cast-iron hopper-shaped frame, glazed in front and ends, but left open about 2 in. wide at the top, the opening being covered with fine wire gauze. The lower portion of all the windows will also be constructed so that the middle part, about 1 ft. in width from top to bottom, can be unlocked and turned upon a centre, and thus a flood of pure air be admitted when desired.

In addition to this, air-bricks are built into the wall at intervals, at the level of the ceiling, with fine zinc gauze covering the inside, and a sloping lip projecting about 6 in. from the wall, to give an upward current to the air and prevent down-draught. In order to disperse the stratum of foul gases, which is found to be about the level of what may be called the bed line, or about 2 ft. from the floor, there are a series of hit and miss gratings, lined with fine gauze, and communicating, by means of galvanized iron horizontal tubes in the floors, with the outer air.

The fireplaces are entirely of firebrick back and sides ; and in order more effectually to distribute the heat in the wards and save fire-places, a principle is adopted which has been found to answer extremely well. A flue conveys the fresh air to a chamber at the back and sides of the

fireplace, where it is warmed, and passed by a pipe built in the wall to midway

between each fireplace in some cases, and in others into the single patients' rooms near infirmaries, lavatories, clothes lobbies, linen-chests, and W.C.s and staircases, where by means of a hit-and-miss grating it is let out.

The cost of each asylum, as now altered, is estimated at about 85,000l.

It will be seen that the whole of the buildings are of a plain, substantial

character. No stone is used except in cills and door-steps. In the windows circular heads have been avoided, as entailing expense.

In the wards and elsewhere all the sashes are of cast iron.

The insides of the wards, corridors, stair-cases, &c., will be of brick, with neat joint, and coloured a light green or grey colour.

Leavesden/Caterham administrative block plan, 1868.

Leavesden/Caterham dormitory and infirmary plans, 1868.

The asylum's foundation stone was laid on 22nd April 1868 in the vestibule of the central block by Dr. William Henry Brewer, M.P., Chairman of the MAB. The building contractors, John Chappell and Co., had laid a single-track railway line from Caterham Junction to transport materials to the site. A special train was provided on the line to convey visitors to the opening celebrations.

Caterham administrative block, c.1914.

© Peter Higginbotham

As can be seen in the picture below, the windows of the ward blocks were barred to prevent inmates escaping or jumping from them.

Caterham asylum entrance and ward block, early 1900s..

© Peter Higginbotham

Extensions to the buildings, designed by Giles and Gough, were made in 1873. These included an additional block for 160 females and a recreation hall with a stage. The Caterham site location and layout are shown on the 1910 map below.

Caterham Asylum site, 1910."

Caterham Asylum, 1872

Caterham aerial view from the west.

© Peter Higginbotham

In 1872, in typically gushing prose of the period, an account of the Caterham Asylum appeared in the magazine Good Words:

THE IDIOT COLONY AT CATERHAM.

Having received permission from the Metropolitan Asylum Board to visit their establishment at Caterham, I left London one fine morning in last December for the purpose of examining the building and inquiring into the management of the institution. Possibly the reader may conceive that a desire to occupy myself for a whole day in a building containing one thousand six hundred imbeciles and harmless lunatics, whose misfortune I was incompetent in the slightest manner to relieve, betrayed somewhat of a morbid taste. This, however, was hardly the case. I was actuated rather by a desire to witness the gigantic efforts which I had been informed were made at Caterham to relieve such an immense amount of human suffering. Indeed, I laboured under a certain alarm lest the scenes I should witness might prove too painful to me. This alarm increased as I neared the building, till at length it became positively oppressive. My fear, however, was groundless. True, there was a vast amount of misery within the walls of this immense establishment ; but the painful sensation which I had felt in a short time became lost in the interest and admiration excited by the untiring humanity, and the admirable skill and discretion displayed in the management of the patients.

I will not stop to give any lengthened description of the building itself. As the reader may imagine, it is of immense size. The façade, though destitute of that meretricious ornament which architects of the present day are inclined to heap on buildings intended for charitable uses, is in good taste and by no means unpicturesque. The blocks of buildings in the rear, dedicated to the use of the patients, are unpretending so far as architectural elevation is concerned, but they seem well constructed ; each being three stories in height, with numerous long windows, so as to insure a perfect ventilation. On entering the building I was soon joined by Dr. James Adam, the physician and principal official of the establishment, and Mr. George White, the superintendent. Having delivered my credentials, the doctor proposed that I should at once visit the building-wards and offices, and have their uses explained as we proceeded. All questions that I might ask, he assured me, should be fully and candidly answered.

As the dinners for the patients were now ready, it was suggested that I should first visit the kitchen. This is a vast lofty hall in the centre of the building. Had it not been for the smell of cooked food which pervaded the place, and the fact of my having been told that I was in a kitchen, I should hardly have recognised the uses to which it was devoted. Not a particle of fire was to be seen anywhere, and yet dinners for one thousand six hundred persons, not including the staff of assistants, had been cooked in it. Stoves, furnaces, cauldrons, and other apparatus were heated by gas, which is manufactured on the premises. All the roasting and baking were done in closed closets, so that the smallest possible quantity of odour escaped into the hall. Huge cauldrons, also heated by gas, were in the centre, and were used for boiling fish, vegetables, and puddings, and for making soup. There were also huge cylindrical machines, the uses of which I did not understand, as they were not in operation at the time of my visit. But I was informed that they were for making tea, coffee, and cocoa for the patients ; tea being given them in the evening, and coffee or cocoa for breakfast. I should also mention that a most scrupulous cleanliness was discernible, not only over the whole of the vast kitchen, but in every machine and utensil used for cooking.

I now examined the food, all of which appeared to be of excellent quality, whilst the cooking was perfect. There were roast and boiled joints, minced meat for the aged and epileptic, several kinds of fish, and custard and other puddings, besides excellent ragouts of Australian mutton, stewed with fresh vegetables of different descriptions. All was cooked in a manner that would not have disgraced the chefs of the Carlton or Reform Clubs.

The dinners were now given out to persons in the corridors to be taken into the wards. To accomplish this the whole kitchen staff of officials was in active operation. I inquired of Mr White, the superintendent, how many cooks were employed. "About thirty," he replied ; "four or five are regular cooks or paid assistants ; the other twenty-six are patients." Yes, reader, these well-cooked dinners were the handiwork of twenty-six idiots (poor creatures, who at home would not have been trusted to put a kettle on the fire), superintended by three or four skilled servants. And the cooking was not only done by complicated gas machinery, but the gas itself had been manufactured on the premises by the patients, superintended by a few skilled artisans.

After quitting the kitchen I was conducted by the superintendent into the store-room of the victualling department. How shall I describe it? It was hardly a shop, and yet it was not a warehouse. It appeared to contain as much provisions as the Civil Service Stores, yet not of such various descriptions. There were chests of tea, piled on one another some eight or ten feet from the ground ; huge quantities of cheese, butter, sugar, and treacle, whole flitches of bacon, and scores of tins of Australian preserved meat. To prove the quality of the latter, a ten lb. tin was opened, and its contents, which presented a solid mass, in form something like brawn, was severed down the middle for my inspection. Certainly meat of finer quality could not be imagined. There were also large tins of ground coffee and cocoa, ready for the next morning's breakfast. I particularly noticed many huge balls hanging from the ceiling, and I was told that each of these — one hundred and eighty in number — was a Christmas plum-pudding for the patients. Nothing could exceed the order, cleanliness, and regularity of the arrangements.

I was now conducted into the bakehouse, which in size corresponded with the kitchen and the store-room. Here, again, I found the labour of the patients utilised as thoroughly as in the kitchen. Nor was it unskilled labour. The machinery employed for kneading the dough, and shaping the loaves, was of a most complicated description ; and yet I was told, the patients were so well used to their work, that an accident had never occurred among them, either from the machines in motion, or from the fire of the ovens. The quality of the bread, I need hardly say, was excellent.

Our next visit was to the laundry, and here my surprise was as great as in the kitchen and bakehouse. No fewer than eighty-six women were employed at the time. Of these, six were professed laundry-maids, the others female patients. Although the place, which is a large, lofty, well-ventilated hall, was a scene of great bustle, yet the most perfect order and regularity prevailed throughout. The heavier portion of the washing was done by machinery. Some of the machines, from their size and the force employed, were not without danger ; and yet because of the excellent training no accident had ever occurred. Of the enormous amount a labour got through in the laundry some idea may be gathered from the following fact. Noticing a heap of linen in the centre of the hall, in size somewhat resembling an overturned hay-load, I inquired whether that was the accumulated linen that had been used during the last week?

"Last week, sir!" said one of the laundry-maids. "Why, that is yesterday's washing alone. We wash every day the used linen of the day before."

"How many articles do you on an average, wash daily?" I inquired.

"Our daily average, sir, is about two thousand pieces."

As to the quality of the washing, it was excellent,— certainly if a snow-white colour is any test, nothing could be better. Noticing some caps very neatly got up, I was told that they belonged to the female patients employed in the laundry, who, profiting by the opportunity afforded them, employed some little portion of their time in this very pardonable love of personal adornment.

The doctor now conducted me to the female wards. The block I first visited consisted of three floors. The ground-floor was used as the day-room of the patients, eighty in number. They were then assembling for dinner, and took their places at the four tables (twenty at each) with the greatest order. A paid official superintended at either end of the table, served the portion to each patient, and carefully watched their behaviour. I inquired whether any difficulty or jealousy arose upon points of precedence or such-like among the female patients.

"Hardly ever, sir" replied the Superintendent. "They are, as a rule, very well behaved."

I next visited the two upper or sleeping wards. The bedding and appointments appeared to be of excellent quality, and a scrupulous cleanliness pervaded the whole. Each ward contained beds for forty inmates. They are under the constant supervision day and night ; two nurses having the care of every forty patients during the day, and these in the evening are relieved by two others.

I then, in company with Dr. Adam, visited several other of the female wards, in all of which I noticed the same regularity, comfort, and care. It being near Christmas at the time of my visit, the whole of the female wards had been decorated with wreaths and mottoes applicable to the season, and with artificial flowers, all made by the patients under the superintendence of the nurses. Some of the wreaths and groups of flowers were not without artistic taste. Among the mottoes was one of very frequent occurrence — "God bless the Prince of Wales, and may he soon be restored to health;" — another proof that every class of the population sympathised with His Royal Highness in the misfortune which had fallen upon him.

I inquired of Dr. Adam whether any other of the inmates were employed in useful occupation besides those I had seen in the kitchen, bakehouse, and laundry. In reply he told me that by far the greater part of the work, both skilled and unskilled, of the immense establishment was performed by the idiots and lunatics ; the latter being of that class of patients in whose case it is hardly possible to draw the line between imbecility and insanity. As the whole system adopted in the asylum for the amelioration of the patients is carried to such a degree of perfection — the machinery, though complicated, yet acting harmoniously as a whole — a short description of the theory in addition to the practice may not be uninteresting to the reader. As I understood Dr Adam, it appeared to be nearly as follows:

Although the history of the great mass of the patients who are brought into the asylum is generally but little known, they are evidently drafted from the poorest portion of the population. The sources from which idiocy, and idiocy combined with insanity, are derived, are evidently want, intemperance, poverty, irregular living, and in an immense number of cases, habitual drunkenness in the parents. In fact, it may unhesitatingly be stated, that the most prolific cause of idiocy among the poorer of our working classes is drunkenness in the parents. Generally speaking, the case is still further exaggerated by the persecutions and petty annoyances to which many of them have been subjected. To this may be attributed the irascibility and ill-humour they show when first admitted; for the idiot, as proved by the effect of the treatment in the asylum, is not as a rule irritable, or wickedly disposed unless under provocation. The first efforts of the superintendents on the admission of fresh patients is to cure them of this irritability and quarrelsomeness. The method adopted, though simple in the extreme, is exceedingly efficacious. No arguments are used to show the poor creatures the wickedness or folly of their behaviour ; no threats of punishment are held out to them. The only discipline used is that of unremitting kindness, and thus the exciting cause of irritability being removed, their temper gradually smooths down, and in a very few weeks after their admission into the asylum favourable progress is noticeable. And I may add, so efficacious is this gentle treatment, that there is not in the whole establishment a lock-up room for refractory patients, or any other means of punishment or physical restraint whatever.

But the wandering life, the privations, sorrows, and persecutions which these poor creatures have endured, have caused in a majority of cases a great deterioration of their original mental faculties, slight as they were. The system adopted to remedy this is to try to fix the mind on some definite object combined with labour. For example : In one of the female wards, I noticed that some of the windows had netted curtains, and was informed that these had been made by a poor old lady, who, when she entered the asylum was irritable and irascible to a troublesome degree. Nor did she appear capable of fixing her thoughts for five minutes on any one subject. At last, by some chance, she became possessed of netting materials, and it was noticed that when occupied with these she was much quieter. A clue was now discovered to the amelioration of her condition, and the doctor asked her whether she would like to net curtains for the whole of the ward. She willingly agreed to do so, and, a quantity of cotton having been provided, she commenced her apparently interminable labour, working on hour after hour, not only pacified, but much pleased with her occupation. After some days a decided improvement was noticed in her tone of mind, and she soon became as tractable as any patient in the ward.

The reader may possibly imagine that in course of time and by practice the old lady would be able while occupied with her work, to turn her mind to other subjects, and the concentration of thought at first attained would thus be lost. But such is not the case. Although persons in perfect mental health may go mechanically through the operation of netting, their minds occupied during the time on some totally different subject, the weak mind of the idiot is fixed constantly on the work, and a healthier tone is soon developed. The same rule is adopted with all the other patients capable of occupation, whether male or female. Those who are drafted off to the kitchen are employed solely in cooking, whilst in the other departments the same individuals are generally kept to the same labour, and their thoughts being thus concentrated on one occupation, the general tone of the mind becomes healthier.

The reader would hardly believe what perfection in several branches of skilled labour has been reached by these poor creatures, the majority of whom, prior to their entrance into the Asylum, had never done a day's useful labour in their lives. Take one example from among many : Dr. Adam conducted me into the female workroom, where the dresses of the patients were cut out and delivered to the different wards to be made up. It was a long and lofty room, in which were many large tables, covered over with linen and woollen cloth. I forget how many idiots were being employed there at the time, but they were very numerous, and, although superintended by two or three professional dressmakers, the dresses were not only made by themselves, but cut out likewise. The reader may be curious to know the quantity and quality of work done in this co-operative idiot dress establishment. The following items, which I received from the superintendent of the department, will give some idea of the magnitude of the operations carried on in it. During the year 1871 the patients had made no fewer than 1,729 petticoats, 1,816 aprons, 4,537 caps, 1,729 dresses, besides the whole of the linen used in the establishment,— such as sheets, table-cloths, chemises, &c., in all amounting to 18,115 articles.

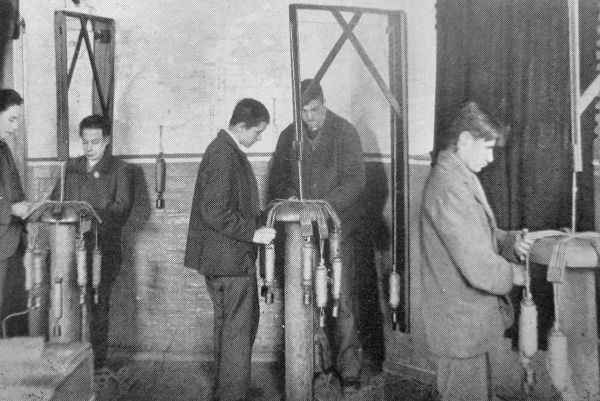

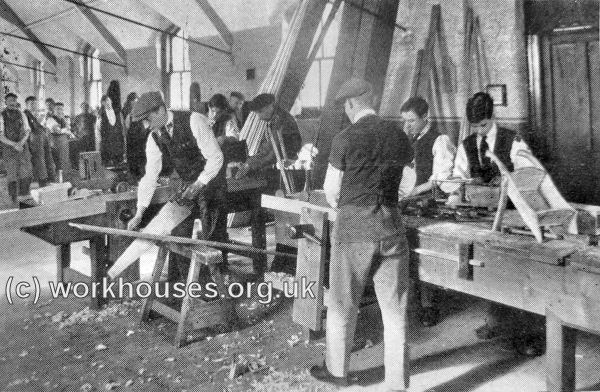

On the male side the same order and regularity prevailed as on the female. In the workshops I noticed several persons employed on labour which, at first sight, it seemed hardly possible that the idiot's mind could be brought to understand, or his hands to perform. Shoemaking and tailoring employed a great number. Noticing in the workshops of the shoemakers some very dangerous looking knives, I inquired whether it was not imprudent to leave such weapons in the hands of those who might use them offensively. I was told, however, that no accident had ever occurred among the workmen, and that the knives and awls had never been used as weapons of offence. Besides those at work in the shoemaker's shop, I found that no fewer than 79 were employed in the cleansing and general economy of the wards, 17 in the upholsterer's shop, 121 in the grounds, besides several others in the gas-house, the engine-house, the engineer's office, and the mess room, amounting altogether to 300 of the male patients. These, added to 452 of the female idiots and lunatics, make a grand total of 752 patients employed in what may be termed skilled and profitable labour. The remaining portion of the inmates are either too old, too infirm, or too young to be made useful, though the labour of many of these is occasionally utilised to the fullest degree consistent with their well-being and health.

I afterwards visited the garden and grounds, and the engine house. Here again I noticed specimens of gardening that might not have disgraced the market-garden grounds of Fulham. Yet by far the largest portion of the labour had been performed by poor creatures, who, till they entered the Asylum, were probably ignorant of the way to handle a spade. I was also shown a piece of ground of about three acres which was being laid out for a cricket-field — the draining and all other work being done by the idiots. In fact, there is no doubt that in the course of a few years the whole of the grounds, about eighty acres, will be brought into very profitable cultivation by the patients, and thus still further carry out the co-operation principle so noticeable in the Caterham Asylum. Nor is this system of co-operation merely a benefit to the health and comfort of the patients themselves ; it is a great advantage — and will shortly be more so — to the metropolitan ratepayer. So admirably does this system work, that, notwithstanding the good food, good cooking, and excellent clothing bestowed on the inmates, the cost of each adult is not more at the present time than 1s.1d. a day ; being less, in point of fact, than the cost of a pauper child in the Union schools at Sydenham or Hanwell.

Two other subjects remain to be noticed — the care and management of the adult idiots. In one of the courts in the centre of the building stands a large, handsome, well-fitted chapel, in admirable order. Here prayers are said morning and evening by the chaplain, and service is performed twice on Sundays. No patients are requested to attend, it being left entirely to their own inclination. Possibly the reader may be of the opinion that a subject so serious ought not to be left to the unguided discretion of the idiot patient. But even, if without compulsion the idiots were advised to attend service, it would be difficult, to obtain better or better conducted congregations than are to be seen every Sabbath-day in the chapel of the Asylum. Even of those occupied in labour no fewer than three hundred attend, daily, morning and evening prayers. On Sundays the chapel is filled to overflowing, the whole six hundred seats being occupied, and many others would willingly attend were there room. And be it understood that the idiots do not go to chapel with the purpose of obtaining the favourable notice of either the chaplain, physician, or superintendents, but solely from their own love of religion. True, it is possible that they would be unable to explain many of the prayers offered up, and that some do not clearly understand even one ; yet there is a certain quiet, speechless worship among them, exceedingly curious as well as interesting to witness. One portion of the service is performed by the idiots in such a manner as might serve as an admirable example to many of the congregations in our fashionable London churches. The singing is excellent ; and, although the hymns are of a very simple description, the singers keep in good time, and well together. It is a singular fact that, while all taste for other branches of the fine arts seems to be unknown or uncared for by these idiots, their ear for music is as acute as that of any portion of the population. Nothing pleases them more than to hear a song well sung.

It must not be imagined, however, that serious employments alone are found for the idiots and lunatics in the Caterham Asylum. There are, on the contrary, few communities of the poor who have so much amusement provided for them. In one of the wards I noticed a stage, with the proscenium of a theatre, the curtain down. I inquired whether they had any theatrical performance, and who were the performers.

"We have them occasionally," said Dr. Adam, "but not very frequently. The performers, however, are not the patients, but artists engaged for the occasion."

Entertainments such as those given by Mr. and Mrs. German Reed at the Gallery of Illustration, in Regent Street, are much enjoyed by the idiots ; and any portion of the performance which particularly claims their attention is rewarded by loud and uproarious applause. There seems something almost electrical in this lavish applause. Unfortunately, from the plan of the ward, fully one-third of the audience are unable to see or hear, yet this by no means detracts from their enthusiasm. Those who are the worst placed are as well pleased as their more fortunate companions. How little the real merits of the performance are understood and appreciated by the audience may be judged from the fact that the delight they exhibited at the feats of a number of learned dogs and monkeys far exceeded that shown at the more intellectual pastimes provided for them.

Another of their great treats is the weekly ball which takes place on Wednesday evening. Some few of the patients are musicians, but the principal performers are the officials. In all the different wards I passed I noticed books (the Bible invariably), picture books in considerable variety, and newspapers, not always of the latest date, or apparently much cared for unless illustrated. In fact, it would be difficult to suggest anything left undone to promote the happiness of the patients, that is consistent with the rights of the rate-payers by whom they are maintained.

My last visit was to the children's ward. Possibly this department was the most painful of all to witness. It was indeed lamentable to see so many poor children (fully sixty in number) condemned to pass their life within the walls of an asylum. And in the majority of instances this was from no fault of their own, nor from unavoidable misfortune attending their birth, but from the drunkenness of their parents. I inquired of Dr. Adam whether he considered that the immense buildings at Caterham as well as Leavesden were not in excess of the exigencies of the metropolis, especially when so many other asylums, both public and private, were in existence. He replied that this was not the case; and that vast as were the asylums of Hanwell, Colney Hatch, Leavesden, Caterham, Bethlehem, St Luke's, and others, for the reception of the imbecile and insane, they were still too small for the numbers of applicants waiting for admission. At Caterham they were full to overflowing, and he understood that all the other asylums were in the same condition. I have since learned that so great is the number of patients in excess of the provision made — vastly as this has been increased of late years — that the ratepayers of Middlesex will soon be called upon to spend £200,000 for an additional asylum, capable of holding one thousand persons ; and that, should insanity and idiocy increase in the proportion it has been doing for some years past, the new building will hardly be finished before the attention of the magistrates will be called to provide still further house accommodation for the idiots and the insane of the metropolis. Such being the fact, might not the magistrates, while entertaining the question of building fresh asylums for the reception of the victims of drunkenness, do well to take some steps to diminish the number of public-houses?

But to return to the children. Their condition was possibly more to be deplored than that of the adults, because no healthy occupation could be found for them. As it was a cold day on the occasion of my visit, they were all in the wards ; and though playthings and picture-books in abundance had been found for them, they had a listless appearance which was exceedingly depressing. I inquired whether they were generally tractable, and received the same answer as I did when I put a similar question respecting the adults : — When first they come to the asylum they are generally fractious and irritable, but by quiet and kindly treatment their tempers rapidly improve.

In these wards I met with two cases of that fortunately rare malformation of the skull known as microcephalis — human beings born with so slight a portion of brain, that they have scarcely more perceptible brow than is to be found in the superior species of the canine race. Of the two children so afflicted in the Caterham Asylum, one was a boy between four and five years old, the other a girl about nine, both children of the same mother. As the latter was asleep at the time of my visit, I did not disturb her ; but the boy, when he saw me, appeared somewhat alarmed, and gazed in a terrified manner around him till he saw the head attendant of the ward, who, noticing the poor little fellow's frightened look, advanced towards him. As the warder took up the child, the latter placed one of his arms round the man's neck, and the frightened expression vanished, one of perfect security taking its place. He looked at me now without the slightest fear, and even smiled.

With the best willingness to detect any objectionable feature in the Caterham Asylum and its management, I could find but one — its distance from London. Many friends of the patients, all of whom were poor, might on this account be deterred from visiting them as often as they would otherwise do. This objection was readily admitted by Mr. White, the superintendent ; but at the same time he told me that it had been greatly modified by the charity and kind feeling of the Board of Directors of the South-Eastern Railway Company. When brought under their notice that the railway fare deprived many of the poor patients of their greatest treat — a visit from their friends — the Directors, with a liberality worthy of all praise, made a reduction of forty per cent in the third class tickets to all persons visiting their relatives in the Asylum. The result is that the number of visitors has increased threefold since the reduction was made.

And now, with thanks to Dr. Cortis, the Chairman of the Caterham Committee, to Dr. Adam, to Mr, White, and to all the officials, and last, not least, to the Directors of the South-Eastern Railway Company for their liberality and humanity, I take my leave of the idiot colony at Caterham.

WILLIAM GILBERT.

At first, both adults and children were admitted to Caterham and Leavesden. However, within a year or two, the medical superintendents had persuaded the MAB that they should be separated. From 1873, children were housed in the temporary smallpox and fever hospital at Hampstead and teachers appointed in an experiment to try educating "idiot" children. This arrangement ended when the Hampstead accommodation was needed to deal with a new smallpox outbreak in 1876. In 1878, after a temporary move to a disused orphanage at Clapton (later the Salvation Army Congress Hall) they were moved to a newly erected children's institution at Darenth in Kent. However, when Caterham and Leavesden became filled to capacity, adult patients were also placed at Darenth.

By 1900, Caterham, Darenth and Leavesden were housing almost 6,000 patients. In the three decades since their opening they had dealt with nearly 24,000 cases of which around 6,000 were discharged — about 1,400 of these were described as 'recovered', 1,500 as 'relieved', and 1,500 as 'not improved'. Most of the remainder were moved to county asylums.

Caterham Asylum 'crippled' children's ward, c.1923.

© Peter Higginbotham

Caterham Asylum workshop, c.1923.

© Peter Higginbotham

Caterham Asylum carpentry class, c.1923.

© Peter Higginbotham

Caterham Asylum children's training centre, c.1923.

© Peter Higginbotham

From 1920 to 1941, the asylum was known as Caterham Mental Hospital. In 1930, administration of the hospital passed to the London County Council. It then had 323 beds plus a nursery unit. In 1941, it became St Lawrence's Hospital and continued to provide care for the mentally handicapped. In 1974, the hospital came to public attention with the publication of the book Tongue Tied by Joseph ('Joey') John Deacon who had been a patient at the hospital since the age of eight in 1928. This was followed by the TV documentary Silent Minority in which the hospital featured in an unfavourable light.

The site has now been redeveloped for housing and all the asylum buildings demolished with the exception of a single block at the south-east corner.

Former Caterham surviving block, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham

Some idea of the appearance of the other Caterham buildings can be gained from the surviving entrance and chapel buildings at Leavesden.

Leavesden administration block from the south, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham

Leavesden chapel from the south, 2004

© Peter Higginbotham

Staff

Inmates

Records

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Has virtually all the surviving records for the Metropolitan Asylums Board and its instititutions. Search their catalogue at https://search.lma.gov.uk/.

Bibliography

- Ayers, Gwendoline, M. (1971) England's First State Hospitals and the Metropolitan Asylums Board (Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, London).

- Deacon, Joseph John (1974) Tongue Tied (National Society for Mentally Handicapped Children)

- Powell, Sir Allan (1930) The Metropolitan Asylums Board and its Work, 1867-1930. (MAB, London)

- Gilbert, W (1872) The Idiot Colony at Caterham (in Good Words, 13, 271-277)

Links

- Malster, Robert (1994) St Lawrence's: the Story of a hospital (Caterham: Lifecare NHS Trust)

- Andrew Roberts' asylums website.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.