Rules and Punishment

One source of insight into life in the workhouse comes from the lists of rules under which workhouse operated. These were often printed and prominently displayed in the workhouse, and also read out aloud each week so that the illiterate could have no excuse for disobeying them. The rules for Aylesbury parish workhouse from 1831 outline the daily regime:

Aylesbury parish workhouse rules, 1831

After 1834, the Poor Law Commissioners issued detailed orders about every aspect of the running of a poor law union and its workhouse. In 1847, 233 separate regulations or 'articles' were brought together as part of the Consolidated General Order which governed workhouse operation and administration for the next sixty years. For example:

ART. 119.—No written or printed paper of an improper tendency, or which may be likely to produce insubordination, shall be allowed to circulate, or be read aloud, among the inmates of the Workhouse.

ART. 120.—No pauper shall play at cards, or at any game of chance, in the Workhouse ; and the Master may take from any pauper, and keep until his departure from the Workhouse, any cards, dice, or other articles applicable to games of chance, which may be in his possession.

ART. 121.—No pauper shall smoke in any room of the Workhouse, except by the special direction of the Medical Officer, or shall have any matches or other articles of a highly combustible nature in his possession, and the Master may take from any person any articles of such a nature.

After 1834, the breaking of workhouse rules fell into two categories: Disorderly conduct, which could be punished by a withdrawal for food "luxuries" such as cheese or tea, or the more serious Refractory conduct, which could result in a period of solitary confinement. The workhouse dining hall was required to display a poster which spelt out these rules:

Toxteth Park rules poster, c.1900

Workhouse punishment books record the severity of punishments meted out to inmates. Some chilling examples of this can be seen in the "Pauper Offence Book" from Beaminster Union in Dorset. Offences against property, for example breaking a window, received particularly harsh punishment:

| Name | Offence | Date | Punishment |

| Elliott, Benjamin | Neglect of work | 31 May 1842 | Dinner withheld, and but bread for supper. |

| Rowe, Sarah | Noisy and swearing | 19 June 1842 | Lock'd up for 24 hours on bread and water. |

| Aplin, John | Disorderly at Prayer-time | 22 July 1842 | Lock'd up for 24 hours on bread and water. |

| Mintern, George | Fighting in school | 26 July 1842 | No cheese for one week. |

| Greenham, Mary and Payne, Priscella | Quarreling and fighting | 14 Dec 1842 | No meat 1 week. |

| Bartlett, Mary | Breaking window | 21 Mar 1843 | Sent to prison for 2 mths. |

| Park, James | Deserted, got over wall | 4 Sep 1843 | To be whipped. |

| Hallett, Isaac | Breaking window | 25 April 1844 | Sent to prison for 2 months hard labour. |

| Staple, John | Refusing to work | 7 Jany. 1856 | Committed to prison for 28 days. |

| Johnson, John | Refusing to work | 19 Oct 1858 | Cheese & tea stop'd for supper. Breakfast stop's altogether. |

| Soaper, Elizabeth | Making use of bad language in bedroom. Trying to excite other inmates to insubordination. Refusing to work. | 17 Jany. 1863 | Taken before the Magistrate & committed to prison for 14 days hard labour. |

| Note by Chairman of the Guardians: "Would not 28 days be better—J.F.?" | |||

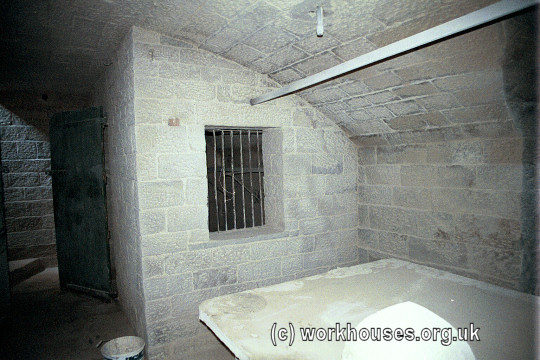

Being "lock'd up" might well mean a spell in the "refractory cell" — this was often underground in one of the workhouse cellars, such as the one at Keighley workhouse:

The subterranean cell at Keighley, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.