Keighley, Yorkshire

Up to 1834

On February 24th, 1767, the Leeds Intelligencer advertised for a master and mistress to manage the workhouse in 'Kighley'. Applicants were invited to contact Mr James Barwick, a grocer in Keighley.

A parliamentary report of 1777 listed local workhouses in operation in Keighley (for up to 40 inmates), Bingley (40), and Haworth (28).

From 1790, Keighley's workhouse was in rented premises at Exley Head, to the south-west of the town on the Oakworth road.

}"

}"

Keighley's Exley Head workhouse site, 1852.

Bingley's workhouse dated from 1726 when a house called the Tavern on Myrtle Place was taken over - the Vestry decreeing that "no house rents shall be paid". The establishment features little in records until, in 1758, the Vestry resolved that "the workhouse shall with all convenient speed be put into proper order" and a master and mistress appointed. In 1776, the Vestry set up a standing committee "to act as guardians and trustees of the Poor" to replace the local overseers - a move which appears to pre-empt Gilbert's Act of 1782. The committee was to meet fortnightly, with absent members being fined sixpence. The workhouse was to be restricted to the aged, the infirm, and children. However, out-relief still predominated, with workhouse residents even being offered to move out in return for a monthly payment of two shillings.

Bingley Myrtle Place workhouse site, 1850.

After 1834

Keighley Poor Law Union was formed on 10th February 1837. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 16 in number, representing its 6 constituent parishes and townships as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of Guardians if more than one):

West Riding of Yorkshire:

Bingley and Micklethwaite (4), Haworth (3), Keighley (6), East and West Morton, Steeton with Eastburn, Sutton.

Later Additions (all from 1894): Oakworth, Oxenhope, Stanbury. [Prior to 1849 these places were subsumed under Howarth.]

The population falling within the union at the 1831 census had been 28,296 with parishes ranging in size from Steeton with Eastburn (population 859) to Keighley itself (11,176).

In common with a number of other West Riding manufacturing towns, Keighley was a centre of resistance against the New Poor Law, introduced in 1834. A major protest demonstration took place in the town on March 22nd, 1837, when Alfred Power, one of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioners from London, was attending a meeting of the Board of Guardians at the Mechanics Institute. As he tried to leave the meeting, to which the public had been admitted, he was manhandled and his overcoat was torn. As he made his way to the Devonshire Arms, he was followed by a great crowd of people shouting and hissing at him. He left the town shortly afterwards and headed for Bradford where he hoped to receive a more welcoming reception.

The Keighley Guardians for many years resisted the construction of a central workhouse, preferring instead to give the "dole" during occasional periods of high unemployment. Instead, the former township workhouses at Bingley and Exley Head were kept in use. An 1851 tithe award records a cottage in Haworth being used as a Vagrants' Office for dealing with passing tramps and vagrants.

The Sagars Affair

At the end of 1857, the Exley Head workhouse became the centre of widespread publicity after the master, John Sagar, was accused of poisoning his wife Barbara who died on December 19th after a week's illness. The coroner's inquest showed that her had appeared to have resulted from arsenic poisoning. It was also alleged that her symptoms during her final days were consistent with arsenic poisoning.

The Sagars had been married for nineteen years and had had nine children, all of whom were dead. At the time of Barbara's demise, the couple had been master and matron of the workhouse for six years, prior to which John had been a painter, a druggist for a short while, and then a publican for two years. John Sagar, described by one newspaper report as 'a short, square-built fellow, of middle age, and with countenance "villainously low"' was said to have once locked his wife in the workhouse mortuary, and had also handcuffed her to a bedstead for mistreating some children in the workhouse. The Sagars were also alleged to have been involved in a bizarre triangle with Ann Bland, the twenty-two-year-old daughter of one of the Board of Guardians. Bland claimed that Mrs Sagar had invited her to share the Sagars' bed where she had lost her virtue.

On 16th March 1858, Sagar went on trial at York Assizes for what the prosecution described as a 'most cowardly and dastardly' murder. Their case was largely based on evidence from the physicians who had conducted the post-mortem on Mrs Sagar's body which detailed the traces of arsenic they had found in her internal organs. There were also a number of allegations concerning Sagar's mistreatment of his wife. For the defence, a number of witnesses testified that he had invariably treated his wife kindly. The most decisive testimony came from Mr John Milligan, surgeon and medical officer to the Keighley workhouse and union, who had attended Mrs Sagar during her final days. He expressed great doubts about her death being caused by arsenic poisoning. The presence of the substance in her body was, he suggested, was readily explicable by its absorption through the skin from various ointments she had previously used. Instead, he attributed her death to severe inflammation of the stomach which had arisen from natural causes. Following Milligan's evidence, the prosecution withdrew their case and Sagar was pronounced not guilty.

The Oakworth Road Workhouse

The Poor Law Commissioners eventually got their way and a new union workhouse was erected in 1858 at the north side of Oakworth Road in Keighley. Its construction cost £7,100. The architect is unknown but the layout similar to that of Ripon workhouse built four years earlier. The Keighley workhouse location and layout are shown on the 1908 map below.

Keighley Oakworth Road workhouse site, 1908.

An administrative block stood to the west of the site entrance on Oakworth Road. It contained the board-room, committee rooms, Master's office and receiving wards.

Keighley administration block from the south-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A new porter's lodge and male vagrants' cell-block were erected at the east of the entrance in 1887. The 17 work cells each contained an iron bed and a handle attached to a corn-grinding device which required 8,800 turns to grind 4 bushels (32 gallons) of corn. There were also two association wards, one for 23 men and one for 13. Female casuals were housed on an upper floor of the block.

1

1

Keighley lodge from the south, 1971.

Keighley lodge from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1887, local bookseller C.W. Craven spent a night undercover in the Keighley tramps ward and published an account of his experience in A Night in the Workhouse.

The main building provided male accommodation at the east, and female at the west. The dining hall stood to the rear.

Keighley main building from the south, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Keighley, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

What is thought to be a rainwater-harvesting device was located in the north-west courtyard.

Keighley north-west courtyard, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

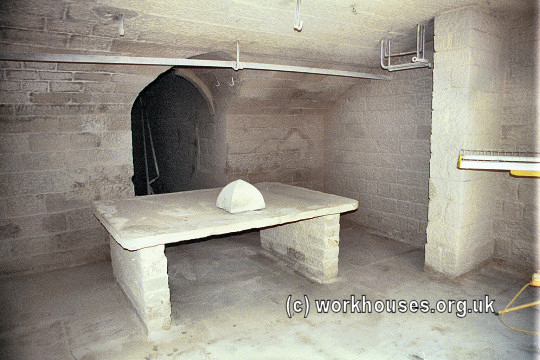

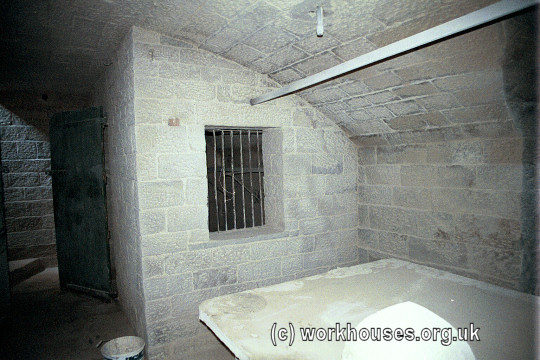

The building had extensive cellars used for storage.

Keighley cellars, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A barred room in the cellars may have been used as a refractory cell where inmates who misbehaved spent a few hours in solitary confinement.

Keighley cellars barred room, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A laundry stood to the north-west of the main building.

Keighley laundry from the north-west, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

The floor of the laundry contained brass rails for drying-racks to move along.

Keighley laundry interior, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

A bakehouse stood at the north side of the main building. A separate male infirm block stood to its north.

Keighley bakehouse (left) and male infirm block from the south-east, 2000.

© Peter Higginbotham.

By the late 1890s, the Keighley Board of Guardians included several female members.

Keighley Board of Guardians, c. late 1890s.

In August, 1900, the Board of Guardians decided that certain workhouse inmates should be sent on holiday to the seaside, a proposal that did not meet with the approval of the Local Government Board. A press report from the period describes the incident:

At the Guardians' meeting on Wednesday it was stated that the inmates in question did work equally as well as paid officers, and were quite content with their lot, and though they were not actually ill they required a change. The ruling that the Guardians must wait till the inmates were actually ill before incurring expenditure was regarded as unwise, and certainly not economical, and, in effect, the meeting decided to disregard the authority of the Local Government Board. and to send four of the women inmates to the seaside for a week. The cheque for the cost was signed ten or a dozen Guardians.

Seaside trips for the elderly inmates became an annual event. In June 1920, a party including one 92-year-old had an outing to Morecambe.

Some of the elderly Keighley inmates who visited Morecambe, June 1920.

© Peter Higginbotham.

In 1930, the Board of Guardians was abolished and the West Riding Council took over the site. An architect's report on the buildings found them in fair repair, although the internal decorations required serious attention. Lighting throughout the establishment was by electricity, and some central heating was installed. There total accommodation provided at that date was for 237 inmates, including 41 infirm men and 6 infirm women, and 56 males and 6 females in the casual wards.

Keighley Workhouse plan, 1930.

From 1930, the site became Keighley Public Assistance Institution, also known as Hillworth Lodge. In 1940, the building was used to accommodate 120 elderly evacuees from the London blitz. After the war, it continued in use as an old people's home and was later occupied by Keighley College. In 2000, the site was redeveloped for residential use.

Fell Lane Infirmary

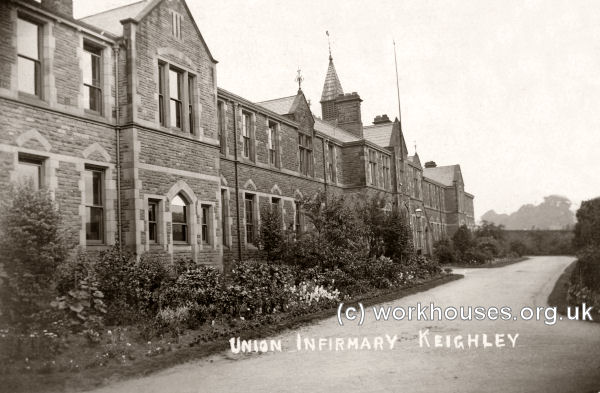

In 1871, Keighley Union erected an infirmary on a separate site on Fell Lane to the west of Keighley.

Keighley Fell Lane site, 1908.

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. On their visit to Keighley's Fell Lane infirmary, the commission found that work was in progress to extend and improve the buildings. They noted, however, that the infirmary was (nominally, at least) under the authority of the workhouse master. As was often the case elsewhere, pauper assistants were used for tasks such as washing, bathing and feeding the patients. The commission urged that the infirmary be made into a separate establishment, under the control of a superintendent nurse. It was also recommended that the nursing staff be increased and that the paupers be less involved in nursing care. A further suggestion was for the hospital to become a place of training for workhouse nurses. Further details are available in the full report.

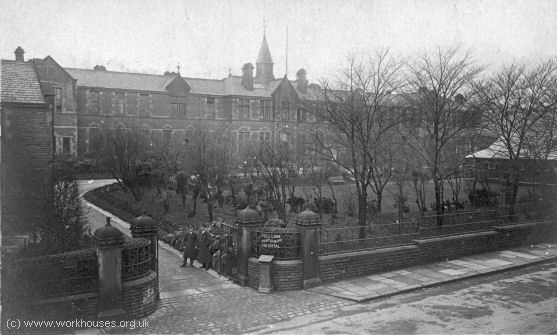

Keighley Fell Lane Infirmary, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

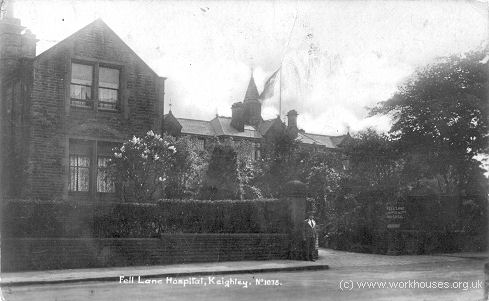

Keighley Fell Lane Infirmary, c.1905.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Keighley Fell Lane Infirmary, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

From 1904, to protect them from disadvantage in later life, the birth certificates for those born in the workhouse infirmary gave its address just as 121 Fell Lane, Keighley.

During the First World War, Fell Lane served as an auxiliary military hospital.

Keighley Fell Lane Infirmary, c.1915.

© Peter Higginbotham.

Like the main workhouse, the Fell Lane infirmary was surveyed by the West Riding County Council when they took over control of the site in 1930. Withe the exception of a recently erected nurses' home, the buildings were judged to be "very unsatisfactory" and required totally rebuilding on the same or on a different site. The atmosphere in the establishment was said to be "dull and depressing". The bulk of the patients were male and female imbeciles, male and female tuberculosis cases, paying maternity cases, and children.

Keighley Fell Lane Infirmary, 1930.

The site subsequently later became St John's Hospital but finally closed in 1970. The buildings have now been demolished.

Children's Homes

By the early 1900s, the Keighley Union was operating a number of children's scattered homes. In 1908, these were located at 18 & 30 Clarendon Street, Keighley; Cliffe Street, Keighley; and 16 Haincliffe Road, Ingrow. Another home was later opened at Hillside House, Haworth. Most of the homes housed around a dozen children in the care of a house-parent.

30 Clarendon Street, Keighley

16 Haincliffe Road, Ingrow

Hillside House, Haworth

In 1905-6, a Central and Receiving Home for 50 children was built on Nashville Road, a little way to the west of the workhouse.

Keighley Nashville Road Home site, 1919.

Keighley Nashville Road Home site.

The home no longer exists.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Keighley Local Studies Library, North Street, Keighley, BD2 1 3SX. Holdings include: Guardians' minutes (1837-1930), Letter books (1837-1910); Ledgers (1884-1923); etc.

Bibliography

- Chadwick, A (1996) Skipton and Keighley Workhouses (Ripon Museum Trust leaflet)

- Dodd, EE (1958) Bingley - A Yorkshire Town Through Nine Centuries (Bingley: Harrison)

Links

- Ripon Workhouse Museum and Garden, Sharow View, Allhallowgate, Ripon HG4 1LE.

- BMJ Report on Keighley Workhouse and Infirmary, 1894

- The union's early correspondence with the central poor-law authorities is online on the TNA website .

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.