Chester, Cheshire

Up to 1834

Chester established a workhouse in 1575 when in a building just outside the Northgate near the quarry in the Gorse Stacks was converted for this purpose. In October 1691, the churchwardens of St. Olave's parish requested the lease of land on which to build 'conveniencys' in order to set the poor to work.

Following the Workhouse Test Act of 1723, several parish workhouses were set up in Chester. St John the Baptist opened one in 1724, and by 1730 there was one at Handbridge, in the parish of St Mary's-on-the Hill. Another existed in St Oswald's parish and, in 1751, Chester Cathedral opened its own poor-house. In 1758-9, a House of Industry for use by all the city's poor was erected on Kitchen Street at the north-west corner of the Roodee.

In 1761, Chester formed an incorporation of parishes (Holy Trinity, St Bridget, St John the Baptist, St Martin, St Mary on the Hill, St Michael, St Olave, St Oswald, and St Peter) under a local Act of Parliament which gave it greater freedom in the management of the city's poor relief. The incorporation was governed by the mayor, recorder, justices of the peace, and seventy-four other guardians. The Act also gave control of the Roodee workhouse for a period of 99 years.

At 2am on 24th February 1767, a disastrous fire broke out at the Roodee workhouse used for spinning cotton. The building, which then housed 200 children in addition to the adults, was totally destroyed. The fatalities included sixty children, twelve men and five women — seventy-seven in all. A report in the London Chronicle recounted the horrifying scenes of inmates running naked from the building, while others jumped from windows and the roof. A party of thirty men was employed to dig out the bones and dead bodies but without success — it was assumed that they had all burnt to ashes.

Chester was the subject of a report by Eden in his 1797 survey of the poor in England:

According to the House of Industry's annual reports, it also took in paupers from parishes outside the city, including Blacon, Hawarden, Higher and Lower Kinnerton, Mold, Puddington and Whitby. The annual numbers of inmates rose from 2,724 in 1810-11 to 5,496 in 1812-13 and then, after a fall, to 7,011 in 1817-18.

The House of Industry was extended in 1819 by the addition of a block for pauper lunatics on the west side of the building. This cost about £700 and averaged around twenty-two inmates. A school for 50 infant paupers was added in 1823 at a cost of £523. In 1821, a warm bath was installed in the main house.

Chester Roodee workhouse site, c.1870

Another contemporary account of the Roodee workhouse (Hemingway, 1831) was fulsome in its praise of the establishment:

After 1834

Chester's Incorporation status exempted it from most of the provisions of the 1834 Act. The Roodee workhouse continued in use, with offices and a boys' school located at 34 Bridge Street.

On 20 September 1869, the Incorporation was reconstituted as Chester Poor Law Union. Its operation was overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 19 in number, representing its 9 constituent parishes: Holy and Undivided Trinity (2 guardians), St Bridget, St John the Baptist (5), St Martin, St Mary-on-the-Hill (3), St Michael, St Olave, St Oswald (4), and St Peter. The parish of Chester Castle joined the union shortly afterwards. Then, in 1871, Chester Union absorbed part of the Great Boughton Union, the remainder continuing under the name of the Tarvin Union. The following parishes were transferred from Great Boughton:

Bache, Backford, Blacon cum Crabwall, Great Boughton, Capenhurst, Caughall, Chorlton by Backford, Christleton, Claverton, Croughton, Dodleston, Durham on the Hill, Eccleston, Elton, Hapsford, Hoole, Ince, Lower Kinnerton, Lea by Backford, Littleton, Marston cum Lache, Mollington, Mollington Banastre, Mollington Tarrant, Moston, Newton by Chester, Picton, Poulton, Pulford, Great Saughall, Little Saughall, Shotwick, Shotwick Park, Stanlow, Great Stanney, Little Stanney, Stoke, Thornton le Moors, Bridge Trafford, Mickle Trafford, Wimbolds Trafford, Upton by Chester, Wervin, Woodbank.

In 1874-8, a new union workhouse was erected on Hoole Lane, Chester, at a cost of about £30,000. The design for the buildings was opened to competition and the winning plans were submitted by William Perkin and Sons. The new workhouse had a large T-shaped main building facing to the east, with a separate infirmary to its west and a school to the south. The site location and layout are shown on the 1911 map below:

Chester workhouse site, 1911

The old Roodee workhouse building was subsequently used as a confectionery works by the Cheshire Preserving Company. It was demolished in the early 1900s.

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. Following a visit to Chester, the commission's report noted that patient in the workhouse infirmary had recently died. A pauper employed as a night attendant had been found guilty of manslaughter due to his rough handling of the patient while unsupervised by the sole nurse who was occupied in another block. The BMJ report criticised Chester's crowded infirmary wards and undue reliance on pauper nurses, especially at night-time. It recommended that more fully trained nurses be engaged, ideally under the supervision of a trained medical superintendent. It was also suggested that telephones or bells be installed to improve communication between the wards, the master's quarters, and the medical officer's home. Further details are available in the full report.

In November 1894, the BMJ also reported that:

After 1930, the workhouse became St James' Hospital. In 1948, following the inauguration of the National Health Service, it was renamed Chester City Hospital.

Chester main building from the north-east, 1990s

The former workhouse buildings have now all been demolished.

The union's offices were later at 161 Foregate Street in Chester.

Cottage Homes

In 1900, the union erected a central children's home on the Wrexham Road together with smaller cottage homes at Upton Heath (Long Lane), Saughall (Hermitage Road), and Dodleston (Main Road). All the buildings still exist.

Chester Central Home, 2013.

©Peter Higginbotham

Chester Upton Heath home, 2013.

©Peter Higginbotham

Chester Upton Heath home foundation stone, 2013.

©Peter Higginbotham

Chester Saughall home, 2013.

©Peter Higginbotham

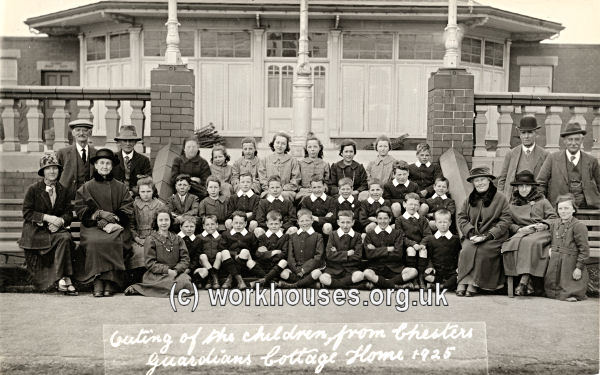

Children at the cottage homes had occasional outings to the countryside and seaside as pictured below in 1925.

Chester Cottage Homes outing, 1925.

©Peter Higginbotham

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Cheshire Archives and Local Studies, Cheshire Record Office, Duke Street, Chester, Cheshire CH1 1RL. Holdings include: Inmates lists (1875-1954); Births (1914-43); Burials and graves in Union cemetery (1882-1900); etc.

Bibliography

- Burne, R.V.H. (1965) The Treatment of the Poor in the Eighteenth Century in Chester (Journal of the Chester and North Wales Architectural and Historic Society, lii, 44-48.)

- Handley, M (2007) Poor Law Administration in the Chester Local Act Incorporation, 1834-71 (in Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol.156).

- Hemingway, J. (1831) History of the City of Chester

- Lewis, C Building Chester's First Workhouse (in Cheshire History, vol 38, 1998-9

- Utting, EJ (1969) The Working of the Poor Law in Chester in Tudor Times (A thesis for the degree of B. Phil. in Local History, presented to Liverpool University)

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.