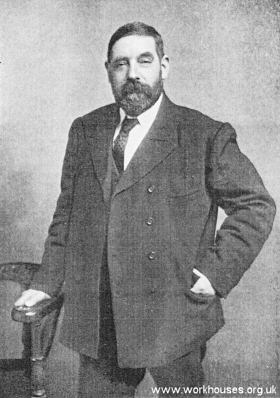

Will Crooks

William Crooks was born on 6th April, 1852, at 2 Shirbutt Street, Poplar. the third of seven children from a poor family in Poplar. His father, George, a former ship's stoker, lost an arm in an accident in 1855, and the family relied on out-relief from the union to survive. When this was withdrawn in 1861, Will's father and the five of the children, including eight-year-old Will, were taken into the Poplar union workhouse.

Three weeks later, the children were transferred to the South Metropolitan District School at Sutton. Crooks later recalled, "every day spent in that school is burnt into my soul." He especially remembered the slow progress of time, especially Sunday afternoons when the children had to sit quietly in the day-room between dinner at noon and tea at six, with only the clock for entertainment.

His mother, Charlotte, managed to find enough money to reunite her family but the experience made a deep impression on him, as did the sight of a bread riot in the winter of 1866 when a lorry delivering bread to the workhouse was stopped and its cargo looted by the starving unemployed.

Will's mother managed to pay the penny a week required for Will to attend the George Green school at the East India docks. He read widely including the works of Dickens, and also the radical campaigning newspapers of the day. As a worker at the East India docks, he began to give Sunday morning lectures at the dock gates on subjects such as trade unions and the co-operative movement, in what became known as "Crooks' College".

Crooks was one of the leaders of the 1889 London Docks Strike where, after five weeks struggle, all the dockers demands were met. In March 1892, he successfully stood as a Progressive Party candidate in elections for newly inaugurated London County Council.

Crooks petitioned the Local government Board to lower the property qualification for election the Board of Guardians from £40 to £10. As a result he was able to stand for election and subsequently became the first working-class member of the Poplar Board of Guardians, the very same board that had forced him and his brothers and sisters into the workhouse. Crooks and his friend George Lansbury were the only two Labour men on a board of twenty-four members. On attempting to visit the Poplar workhouse, Crooks was barred by the Master without whose permission a Guardian could be refused admittance. Crooks and Lansbury raised such a protest about this regulation that it was changed so that a Guardian would have the right to enter a workhouse at any reasonable hour. This small change resulted in an improvement in workhouse conditions across the country.

In 1897 he became its chairman and initiated a programme of reform in the running of the union and its workhouse. This included such things as abolishing uniform and improving the quality of the food.

In 1906, Crooks gave evidence to an official enquiry by the Poor Law Commission about the conditions he found when he first visited the Poplar workhouse:

"Poverty's no crime, but here it's treated like crime," they used to say. Many of them defied the regulations on purpose to be charged before a magistrate, declaring that prison was better than the workhouse.

One day I went into the dining-room and found women sitting on the long forms, some sullen, some crying. In front of each was a basin of what was alleged to be broth. They called it greasy water, and that was exactly what it looked and tasted like. They said they had to go out and wash blankets on that. I appealed to the master to give them something to eat, as they said they would sooner go to prison than commence work on that. Those women, like the men, were continually contriving to get sent to prison in order to escape the workhouse. After a few heated words between the master and me he gave them some food, and none of them went to prison that day.

A few weeks later I was in the workhouse when these same women were creating a fearful uproar.

"Ah, there you are," said the master, meeting me. "Go and look at your angels now! A nice lot they are to stick up for!"

I went to the dining-room. There was a dead silence the moment I entered.

"I am right down ashamed of you," I said. "When you were treated like animals, no wonder you behaved like animals. Now that Mr. Lansbury and I have got you treated like human beings, we expect you to behave like human beings."

They said not a word, and later in the day the ringleaders, without any prompting, came to me and expressed their regret. From that day to this no such scene among the workhouse women has ever been repeated.

The staple diet when I joined the Board was skilly. I have seen the old people, when this stuff was put before them, picking out black specks from the oatmeal. These were caused by rats, which had the undisturbed run of the oatmeal bin. No attempt was made to cleanse the oatmeal before it was prepared for the old people.

Whenever one went into the men's dining-room there were quarrels about the food. I have had to protect old and weak men against stronger men, who would steal what was eatable of their dinners. There was no discipline. The able-bodied men's dining-room on Sundays gave one as near an approach to hell as anything on this earth. It was everybody for himself and the devil take the hindmost. If a fellow could fight lie got as much as lie wanted. If he could not, lie got nothing. Fights, followed by prosecutions at the police courts, were common. The men boasted that prison had no worse terrors than that place. They were absolutely beyond control. They wandered about all over the place, creating all kinds of discord, and even threatening to murder the officers. Two labour masters nearly lost their lives in trying to control them.

The inmates were badly clothed as well as badly fed. Not one of them had a change of clothing. Their under-clothes were worn to rags. If they washed them they had to borrow from each other in the interval. The inmates' clothes were not only scanty, they were filthy. On one occasion the whole of the workhouse linen was returned by the laundry people because it was so over-run with vermin that they would not wash it.

One of the inmates-a woman-who was doing hard work at scrubbing every day, asked me whether she couldn't have a pair of boots.

"Surely," I said, putting her off for the time, "nobody here goes without boots?"

A second and a third time when I came across her scrubbing the floors she pleaded for boots. She raised her skirt from the wet stone floor, and showed two sloppy pieces of canvas on her feet, and that was all she had in the way of boots.

Crooks was also a member of the Poplar Borough Council and, in 1901, became the first Labour mayor of Poplar. He also helped to set up the National Committee on Old Age Pensions, believing that pensions were the only way to keep the elderly poor from entering the workhouse. In 1903, he successfully stood in a parliamentary by-election in Woolwich as the candidate for the Labour Representation Committee.

Will Crooks lived all his life in Poplar and died in London Hospital, Whitechapel, on the 5th June, 1921.

Bibliography

- Haw, G (1907) From Workhouse to Westminster: The Life Story of Will Crooks M.P.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.