Wrexham, Denbighshire

Up to 1834

Eden, in his 1797 survey of the poor in England (and parts of Wales), reported of Wrexham that:

After 1834

Wrexham Poor Law Union was formed on 30th March 1837. Its operation was

overseen by an elected Board of Guardians, 61 in number, representing its 56

constituent parishes as listed below (figures in brackets indicate numbers of

Guardians if more than one):

County of Flint: Abenbury Fechan, Bangor, Erbistock, Hope (2), Threapwood, Trydden, Worthenbury.

County of Denbigh: Abenbury Fawr (or Vawr), Acton, Allington, Bersham, Bieston or Boreston, Borras Hovah (or Bovah), Borras Riffre (or Riffrey), Broughton, Brymbo, Burton, Dutton Cacca, Dutton Driffreth, Dutton-y-Bran, Earlas, Eithig, Eyton, Esclusham Above, Esclusham Below, Gourton, Gwersylt, Gresford, Holt, Llay, Minera, Ridley, Merford and Hoseley, Markiviel (or Marchwiel), Pickhill, Royton, Ruabon (3), Sesswick, Stansty, Sutton, Wrexham Abbott (2), Wrexham Regis (2).

County of Chester: Agden, Bradley, Chidlow, Chorlton, Cuddington, Malpas, Newton Juxta Malpas, Oldcastle, Overton, Shocklach Church, Shocklach Oviatt, Stockton, Wichaugh, Wigland.

Later addition: Rhosllanerchrugog.

The population falling within the Union at the 1831 census had been 34,716 with parishes ranging in size from Chidlow (population 15) to Ruabon (8,353). The average annual poor-rate expenditure for the period 1834-36 had been £10,526 or 6s.1d. per head per head of the population.

Wrexham Union workhouse was erected in about 1838 at a site to the west of Wrexham. The Poor Law Commissioners authorised an expenditure of £6,525 on construction of the building which was intended to accommodate 400 inmates. The workhouse site location and layout are shown on the 1909 map below.

Wrexham workhouse site, 1909.

The workhouse design followed the popular cruciform or "square" layout with separate accommodation wings for the different classes of inmate (male/female, infirm/able-bodied etc.) radiating from a central hub.

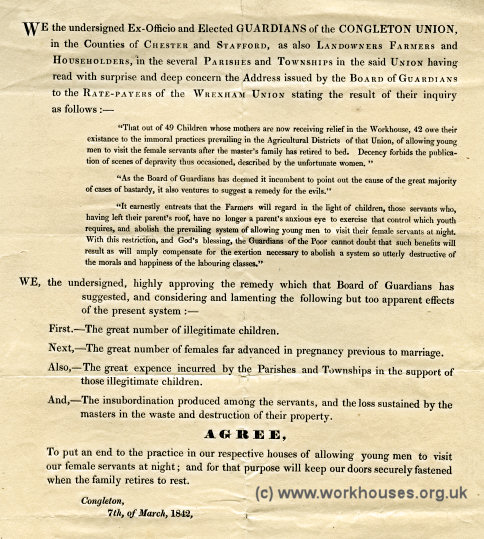

In 1842, it was reported that 42 out of 49 single mothers in the Wrexham workhouse were there because of the prevailing practice of allowing young men to pay night-time visits to female servants in agricultural areas of the union. The news clearly alarmed the board of guardians at nearby Congleton who instigated a campaign to ban such visits within its area, even producing a printed form of agreement to support the scheme.

The form issued in 1842 to ban night-time visits to female servants.

© Peter Higginbotham

From January 1857 until July 1863, the Master of the Wrexham workhouse was William Bragger. Bragger's colourful life and his time at the workhouse have been researched by his great-great-great grandson Andrew Taylor, who has kindly provided the following account.

On his discharge, William and Mary Ann took up residence on the Belle Vue Road, which leads directly to the Workhouse, and William took a job as Superintendent of the Fire Brigade. He also took the post of Sergeant Major in the Denbighshire Yeomanry Cavalry, and received a Chelsea Pension.

In 1856 the Master and Matron of the Workhouse, Daniel and Jessie Kemp, retired after long service and were presented with twenty-five pounds. The job was advertised in the Wrexham press, and 22 applicants sent letters and references; many of them were man-and-wife teams applying jointly. The job description and terms, set out by the clerk Thomas Edgworth (soon to be Mayor of the town) in the Wrexham Advertiser, stated that the Master's salary was to be sixty pounds, the Matron's forty. The Master would be required to enter into a 'Bond' for a hundred pounds, as an insurance that he would faithfully discharge his duties. A porter was also required, on a salary of fifteen pounds p.a.

William's letter of application, along with two others, was printed in the Wrexham Advertiser of Jan 1st 1857. He stated that the statistical paperwork he had been required to prepare in the Army would qualify him to some extent to cope with the paperwork of the Poor Law Board, and said his wife was a good cook who would 'maintain order in her household while being kind in her treatment of the poor'.

The election day for candidates was Jan 15th, and the interview and recruitment processes employed seem today to be rather arcane. First, Edgworth read out all the 22 letters of application and references, to the 39 assembled Guardians, which took an hour and a half. Then, a shortlist was evidently prepared of three candidates, Bragger, Roberts, and Davies. At this stage, individual Guardians who had been impressed by an applicant rose to make a speech of approbation, Mr Challoner rising to propose Bragger as Master. He drew attention to Bragger's Army credentials and his reference from Colonel Yorke, which was based on twenty years' acquaintance. Mr Dashwood Parry seconded the nomination.

Then, Mr Brough rose to propose Mr Davies, a policeman from London, for the job. In adversarial fashion, he criticized his fellow Guardian's recommendation of Bragger, focusing on the fact that nothing had been said of William's wife Mary Ann, which Mr Brough took to be a 'significant omission'. Mr Richardson seconded the nomination.

Then, a third proposal was made, for Mr Roberts, by a Mr Hughes.

Next, the Guardians voted, with Bragger gaining 19, Roberts 17, and Davies 3. The third-placed candidate was knocked out; the voters for Davies fell in behind the other two candidates for a second ballot, which secured Bragger 21 votes for Roberts's 17. William and Mary Ann were duly elected Master and Matron and were called in to hear the verdict.

Thus William and Mary Ann took over at the Workhouse, and a porter, Mr R. Morris, born in Northamptonshire in 1804, was also appointed. On March 7th 1857, the Workhouse housed 223 inmates. Captain Panton RN was currently chairman of the Board, and was none too popular at the time, as he was accustomed to treating the Guardians 'like children'. None the less, in April, he was re-elected and gave a speech, which was met with 'loud cheers'.

The board noted that the Master was allowed 'double rations' and Mr Bragger submitted a diet table for a week totalling five pounds ten shillings, nearly a pound's worth fewer provisions than Kemp had required. It was noted that Bragger preferred 'more coffee and less cheese'. At this stage, Mr Bragger had two children, Eliza and Emma, living in the workhouse with him, according to the rations allowed; his eldest son Charles Harry, born 1841, was probably a tenant somewhere in the area. On June 20th 1857 another child, Albert Green, was christened (he died a year later). At least three other of William and Mary Ann's children had died by this point. William proposed the British Guarantee Society for his bond.

On July 25 of that year, Mr Roberts, auditing the books, criticized William for his book keeping, but William attributed this to the change of staff at the Workhouse. On September 26th, Colonel Tottenham of the Denbighshire Yeomanry requested that Bragger be allowed to take part in eight days of manoeuvres, but the request was 'negatived unanimously'.

The schoolmaster resigned at this time — his job seems to have been a poisoned chalice, with regular changes of employee. A Mr Roberts was one of four applicants chosen to fill the post on November 28th 1857, but he had resigned by April of the next year, to be replaced by a Mr Richardson from Edinburgh. Mr Richardson was sacked in June 1859 for absenting himself without leave and for 'lolling about' in church — initially he had refused to take the children to church services in the first place.

The sanitary and medical conditions of the workhouse seem to have been grim: a doctor's report in December 1857 reported that fever was on the increase. Vagrants were also on the increase and the master was 'at a loss' as to how to deal with them, especially as they seemed to slip in and out, evading the work they were supposed to do in the house. None the less, the provision of a bath 'seemed to please them more than not'. In April 1858 Bragger applied for a silver air tube for a certain Edward Jones who had attempted suicide and cut his throat. In February 1859 an eleven year old girl was found dead in her bed. At least one of the streets leading to the house was described as 'shamefully filthy'. In January 1859 an inmate attempted suicide by throwing himself onto the nearby railway line in front of a train, and 'an engine and twenty carriages' passed over his leg, smashing it 'to atoms'. Mr Bragger wrote in his log book, bizarrely but perhaps appropriately for a hardened Army officer, that 'the man suffered more from shock than from any real injury'!

The Master applied in February 1858 for a rail to fix along the side of the house, next to the adjacent mill race. Mr Dashwood Parry thought that this was a capital idea since he had fallen in the water himself, but the request was refused as a 'mal-appropriation of funds'. Mr Bragger was encouraged to present accounts of profits resulting from the tilling of the workhouse field, and purchased a cow to provide milk.

In spite of the apparently grim conditions at the house, the Guardians perceived by mid-1859 that, far from being a callous master, Bragger was generous and indulgent. Mr Challoner, who had spoken for Bragger at his interview, cited complaints that paupers preferred to reside in the house, rather than take jobs, on account of the fact that they received a better diet and fewer onerous tasks, as well as other 'comforts'. During 1862, the Guardians were surprised that Bragger had not entered 'the nature and length' of punishments to inmates in his log book, only to be told that the former Sergeant-Major avoided inflicting punishments on the poor if he could help it, preferring to govern the house without such sanctions. Furthermore, Bragger ensured that the inmates were dressed differently from each other, rather than in uniform, in order to give them a sense of individuality and to lessen the stigma of being in the house. In the obituary for Bragger in the Wrexham Telegraph of July 1863 it was noted that the master 'seldom' returned from the market without gifts in the form of tobacco and snuff for male inmates, and toys and cakes for the children, and he was in the habit of paying the debts of certain inmates in dire financial straits. On occasion William requested permission to take the youngsters to shows and art exhibitions at the Music Hall.

William's daughter Emma (1855-1915), who was brought up in the workhouse, remembered that the Braggers had squandered a considerable fortune by 'living it up' in the workhouse, and added that there were continual parties. It was noted in January 1860 that the bill for wines and spirits, supplied by Overton and Painter, had escalated dramatically. In March 1863, on the wedding day of the Prince of Wales, the inmates had been gifted free beer; William had given them a pint each early in the day — yet his friend Mr Lester turned up soon after, and promptly bought the beer from the inmates for cash, presumably for himself and William to drink later! Certainly, William often had his Army cronies round and was criticized by the Guardians for entertaining them during working hours; he was told, incidentally, that he was to spend no longer than four hours at a time out of the house with his military friends, and his cavalry activities were curtailed.

It seems that Christmas dinner at the Workhouse was a sumptuous affair, and at the end of 1860 the Wrexham Advertiser noted that the inmates were treated to 'roast beef and plum pudding, which was served out without stint, neither weight nor measure being taken into account'. There was also an allowance of fine ale, and the Master and Matron spared no pains to ensure that 'no Oliver Twist need be afraid of asking for more'.

In spite of the cavils of the Guardians, Inspections by the Poor Law Board were invariably favourable, and in 1860 the Guardians published an open letter in the local press stating that the Wrexham Union 'stands as high as any in Great Britain, in regard to acting legally and yet showing proper kindness to the paupers'. Mr Bragger seems to have repeatedly petitioned the Guardians for various materials to improve the house, which was hardly in good repair, though he was invariably refused any. Additionally, William was in regular touch with the Police, when a woman turned up with a dead child, when an inmate defaulted on maintenance to his wife and child, and, most intriguingly, when a male inmate was charged with 'an offence not fit to be named in print'. Police were pleased by how willingly certain boys in the house had given evidence against the individual.

During the early 1860s, though, the days of good living were to recede in the face of increasing carping criticism from the Guardians, and constant attacks on the Braggers by various employees, notably the crusty porter, Morris, and a sanctimonious Dissenting schoolmistress, Ann Rowley, who had been appointed in December 1862. The porter had complained in July 1862 that Bragger had given certain 'unreliable' inmates various tasks of responsibility, such as keeping the door in the porter's absence: this was viewed as a dereliction of the Master's duty. The Guardians formally read William his obligations at work during their meeting, and Captain Panton tut-tutted, speaking of the 'laxity' in the house. Furthermore, William was criticized for sending some of his inmates out into the fields to make hay, free of charge, for a local man. It transpired this person was Sergeant Lovatt, another Army comrade, who was to bear William's body at his funeral.

The schoolmistress wasted no time in causing trouble on her appointment by writing the Guardians a letter complaining that Mary Ann had required the local barber to give the female inmates a haircut known nowadays as the 'No.1', (i.e., extremely short). The reason for this choice of cut, apparently, was hygiene. In April 1863 the Master and Matron were again called to account by the Guardians, with the schoolmistress as the principal supplier of evidence, regarding the 'industrial training' of the children. An almighty row ensued at the meeting. It seems that the female youngsters in the house were supposed to make their own clothes, and had not been taught any of the requisite needlework; furthermore, William discouraged cookery by the young inmates, owing to wastage of provisions, greed and food-fights! Mary Ann had apparently dismissed her kitchen assistant, Sarah Griffiths, for flirting with the schoolmaster, and she and William regarded the informers against them — especially the schoolmistress, porter, and certain inmates — as a 'clique'.

At the meeting, Mary Ann was furious, popping her cork 'like a bottle of ginger beer', accusing the schoolmistress of informing against her (which had indeed happened). Unfortunately, Mr Edgworth, the Mayor of Wrexham, had paid a visit to the schoolroom and kitchens and seen the evidence for himself. The Braggers were compelled, as a result, to teach cookery and needlework, and the Guardians muttered querulously of the 'want of activity' in the house.

In spite of such altercations, workhouse duties carried on as usual, through early 1863, with the Master informing the Guardians of the post-mortem of a man who had died 'in consequence of a kick he had received from a horse'. New clothes were ordered for tramps, made of sacking and of dimensions appropriate for unisex wear. The clerk of the Guardians noted, on this point, that 'the thing required for success in the world was a light heart and a thin pair of trousers'! Mr Roberts thought that the tramps would be better off in 'knickerbockers'!

Concerns were raised , though, on a weekly basis, as to the tide of effluent — referred to in delicate Victorian parlance as a 'nuisance' - which flowed from the Workhouse into the Mill Race. This festering waste was responsible, apparently, for the spread of typhus in the house, and the Guardians' discussions about it seem to have had no practical effect. It seems that they were unwilling, as usual, to put up the cash to improve conditions.

In early July — perhaps as a result of this — William and the porter, Morris, both became ill. Two Guardians, paying a surprise visit to the house, discovered the Master 'in a very dangerous state,', while the porter was 'dying on his legs' and unable to work. Proceeding further into the house, they discovered disorder and misrule of the sort portrayed in an Edgar Allan Poe short story — lunatic inmates running round mutilating themselves, the Matron prostrate with grief, and no work or duty having been done for a week. The schoolmaster was told to take over the running of the house quam celerrime.

William died on July 4th 1863, allegedly of 'disease of the liver accompanied by haemorrhage'. The porter resigned soon after. At the Denbigh archives at Ruthin, the list of extant Guardians' minutes has those for 1863 were missing, possibly removed, though all other years were present during the period. Is it possible that William's death was in any way suspicious, or that the Guardians were covering up their dithering over dealing with the health hazard caused by the effluent in the mill race?

Though the funeral was supposed to pass off quietly, the Army, Fire Brigade and various other bodies in Wrexham insisted that William be buried with full military honours. Thus, on Tuesday 7th July, Bragger's remains were conveyed in the most solemn and grand manner to the New Burial Ground in Wrexham. Wrexham had never seen anything like it, and as the cortège moved through the streets, crowds of hundreds lined the route, some falling into the procession on the way. The bands, with muffled drums festooned in black crepe, alternately played the Dead March in Saul and a military air from Verdi's Il Trovatore. At the burial ground, the Reverend J. C. Roberts read the oration and panegyrics in melodramatic fashion, followed by three volleys of gunfire, as a mark of respect, directed by Sergeant-Major Walsh. Tear-drops of rain, reported the Telegraph, fell as the Master was laid to rest.

Mary Ann stayed at the Workhouse for a little longer, until the Guardians appointed a Mr and Mrs Higginson as Master and Matron. They were not to last in the job, for by 1868, a Luke Ralph had taken the reins.

After William's death, the carping Guardians complained that he had had so many children they had scarcely been able to accommodate the storm-like rush of new babies at the workhouse, and allegedly William had appropriated more than his allotted share of the rooms to act as nurseries. Family legend has it that William had had nineteen children in total (some of whom had died), though extant public records can only firmly suggest eleven, possibly thirteen.

In 1894, the British Medical Journal set up a "commission" to investigate conditions in provincial workhouses and their infirmaries. Following a visit to Wrexham, the commission's report revealed that "the tone and management of this house impressed us very favourably; the officers seemed to regard their charges as human beings to be cared and planned for." Nevertheless, some improvements were recommended. These included an increased staff of nurses for the sick, the employment of a night nurse, and an end to the use of pauper help in the actual nursing. Better separation of the infants from the adults was also suggested, together with the provision of special accommodation for them when sick, and of a paid official to take care of them. Further details are available in the full report.

By 1900, a large infirmary had been erected at the west of the main workhouse building, with a fever hospital to its west. A separate chapel was added at the north-east of the main building.

In 1930s, the site became Plas Maelor Public Assistance Institution and most of the old workhouse buildings were demolished. The site later became Maelor General Hospital, now Wrexham Maelor Hospital.

Children's Homes

The Wrexham Union established children's scattered homes at Little Acton, Box Lane, Wrexham and Coppenhall House, 81 Benjamin Road, Wrexham. In 1924, the homes could accommodate a total of 44 children.

Staff

Inmates

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- North-East Wales Archives (Ruthin), Ruthin Gaol, 46 Clwyd Street, Ruthin, Denbighshire LL15 1HP. Few records survive — holdings include: Register of inmates (1892-1930); Admissions and discharges (1890-1920); Births and deaths register (1886-1914); Maternity register (1912-30); Ledgers and accounts (1837-1929); etc.

Bibliography

- NEW! Workhouses of Wales and the Welsh Borders. The story of the workhouse across the whole of Wales and the border counties of Cheshire, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Shropshire. More...

Links

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.