A NIGHT IN THE WORKOUSE.

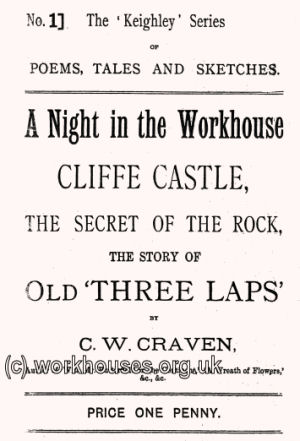

A Night in the Workhouse by Carey Williams Craven was published in around 1887 as No.1 in the The 'Keighley' Series of Poems, Tales and Sketches. Craven, a bookseller and stationer in Keighley was also publisher of the work. His description of a night in the Keighley union tramps' ward was essentially a local re-run of the infamous visit to the Lambeth workhouse by James Greenwood in 1866, whose account bore a virtually identical title.

A Night in the Workhouse by Carey Williams Craven was published in around 1887 as No.1 in the The 'Keighley' Series of Poems, Tales and Sketches. Craven, a bookseller and stationer in Keighley was also publisher of the work. His description of a night in the Keighley union tramps' ward was essentially a local re-run of the infamous visit to the Lambeth workhouse by James Greenwood in 1866, whose account bore a virtually identical title.

HAVING had a desire for a long time to obtain an insight into the vicissitudes of a vagrant's life, I determined to put a plan into execution which should secure to me at least one night's company amongst the guerilla element of modern society. How I succeeded will be found in the following narrative, the accuracy of the incidents of which I am prepared to vouch for.

OBTAINING A TICKET.

This necessary preliminary to a night in the workhouse is very easily accomplished. I found no difficulty in obtaining a suitable rig-out in the shape of an old pair of corduroy trousers, a pair of worn-out shoes, together with a dilapidated coat, specially slashed for the occasion, and a greasy nebbed cap. Thus suitably equipped, I perambulated to the police-station, hung about the door hesitatingly for a moment or two, and then screwed up sufficient courage to enter the office. My appearance was greeted, in cheerful tones, by the officer in charge. "Come forward, young man; do you want a ticket?" To this I answered modestly, " Yes, if you please, sir." In reply to his interrogations I gave him the following information concerning my august self:— Name, Charles Burrell, on the road from Bradford to Burnley; trade, mechanic; age, 28; height, 5ft. 5in. This was written upon a ticket, with which I was duly presented, a duplicate being kept in the officer's book. I thanked him kindly, and betook, myself rapidly up Oakworth Road to the Workhouse.

THE PORTER'S LODGE.

On attempting to enter I was debarred by the stern fixity of the iron gate. After waiting a few moments a window was opened to my right, and a pompous voice exclaimed, "What is it?" I presented my ticket. Again the questions were asked, "Where are you from? Where are you going to? What trade are you?" to all of which I answered as in the first instance. The assistant porter (for I found out afterwards that he wasn't the regular one) then exclaimed in a surly tone, "Pipe and matches!" "What?" replied I. "Pipe and matches!" "Yes, I'll have a pipe and matches." "I want your pipe and matches." "I haven't got any." "Then pass on." I passed on, and after missing my way several times, found myself in

THE OUTER ROOM,

The dimensions of which were about 4½ yards square, Here a regular pauper was in charge, who at once told me to undress myself. Whilst doing this, a piece of dry bread, about 4oz. in weight, was thrown on a board, with the exclamation, "Thear's yer Tommy." On getting my coat, waistcoat and trousers off, and discovering my underclothing, the attendant exclaimed several times, " You don't look as if you hed been on t'road long anyhow." " No! " says I, "this is the first time." He then told me to take my shirt off, and strip myself entirely. "Why take my shirt off?" I asked." Because ther might be sum o' them thear things abaght." he replied. "Are there many of those things round about these quarters?" I further interrogated. "Nay, ah doan't think there'll be so monny, we mostly stove 'em when we find onny." With this answer I was somewhat comforted. When I had undressed myself to a state as naked as when I was born, I was told to tie my clothes up, and place them alongside a series of similar bundles laid against the wall. I was then furnished with a couple of rugs and ordered into

THE INNER OR SLEEPING ROOM,

and the lock turned on me. All was dark as pitch. My bare feet slipped on what I afterwards found was the vagrants' spattle on the stone floor, and the sensation was cold and slimy. It made me think of snails, and worms, and other loathsome creeping things. I felt glad when my hand clutched the boarding on which my limbs were to rest for the night. The men in the room were conversing freely with one another, and after a time I ventured to inquire if there was any room for me. The one in the partition nearest the door answered that I could sleep alongside him, but must be careful not to upset the tin of water at his feet. I made my way as best I could to the place indicated by the sound of his voice, and got my foot accidently into the tin of water, but soon extricated it. Then covering my naked body as well as I could with the rugs given to me, I laid myself on the hard slanting boards, with bare wood as my pillow, to experience

TWELVE HOURS' MISERY.

Do as I would I was unable to make the rugs entirely cover me. There was a cold draught, and I was alternately seized with cramp and neuralgic pains. Now and again I could observe the dim naked forms of the vagrants as they passed to the tub where circumstances of necessity were performed. Needless to say the stench arising from this was anything but pleasant. When the night bad progressed somewhat, the noise arising from, snoring and the men talking in their sleep was incessant. One fellow kept calling out " Sixpence." Another said, " You are there, and I am here, and we've another night and day to do," &c. &c.; As the eight o'clock bell rang for the regular inmates to go to rest, there came a sound of sweet music from the outside, as if a batch of church revivalists was indulging just before separating for the night. The vagrants wondered where the singers came from, and one of them exclaimed, "'The Work house Door.' Have you ever heard it sung? I heard a young woman sing it the other night, and liked it very well." The conversation turned on various topics. Two of the vagrants had been in Skipton Workhouse the night previous, and one of them related how his bread had been carried away by a ravenous rat as big as a cat. The leading features of the Skipton Workhouse were the severity of the labour in stone breaking, and what a "clever beggar" the porter of the establishment was. Other topics were the new waterworks at Barrowford and Colne, and the probabilities of getting a job there. Also what sort of task-work would be likely to be given to us the day following. The tramp next to me complained that he was

SUFFERING FROM DIARRHOEA,

And that the agony he was undergoing was most excruciating. He had asked three times that day to see the doctor, but every time the attendant pretended not to be able to make out what he had said, and the only effort made to relieve the pain was by giving him a tin of warm water to drink. He stated he had travelled from Wakefield, where he did manage to obtain a bottle of medicine; but at Keighley he had been treated "worse than a dog." From him I also learnt that he had been where he was all Sunday, without putting his clothes on, and that he preferred being inside to outside on that day, because people stared so much, and shunned a tramp, particularly if he was badly dressed. He had passed many a Sunday without even breaking his fast. He intended making his way towards Burnley, where, he stated, there was no vagrants' ward, but that tickets were given for a lodging-house.

I DID NOT SLEEP A WINK ALL NIGHT,

And kept fancying "some o' them thear things" were creeping over me. By the time the welcome streaks of morning dawn appeared through the window, my bones felt terribly sore, and I was half starved to death. At about a quarter to seven the key turned in the door, and the order was given for us to "get dressed and bring your rugs in here." Seven naked forms then flitted about in search of their clothes, and commenced to dress. I found the piece of dry bread I had left untouched the night before still remaining. I was asked by one of the vagrants if I wasn't going to take it, and replied in the negative, saying he could have it if he cared to do so. He appeared exceedingly grateful, and at once commenced to devour it. The feet of my fellow-lodgers were of all sizes and shapes, and I had never seen such a collection of corns and bunions before. I found in my pocket a small paper of tobacco, which I shared out as best I could. After getting dressed we carefully folded up the rugs we had slept in, and piled them up in a corner of the room. A few then produced small pieces of soap, which they had secreted about their persons, and endeavoured to wash themselves at the bath, into which at different times I had observed several spit and blow their noses. Whilst

WAITING FOR BREAKFAST

I had a good opportunity of noting the appearance of the room we had slept in. I judged it to be about 8 yards long by nearly 5 yards wide, and at one end was a passage, in which was placed a slipper-bath, a long towel on a roller, and the cess-tub. The boarding on which we had laid was divided into three partitions, each of which was supposed to provide accommodation for three vagrants. Two or three windows, strongly barred on the outside, gave a moderate light to the place. The walls were newly whitewashed, and I noticed several inscriptions written thereon in a legible hand, including the following:-

"Dirty days hath September,

April, June, and November;

From January up to May,

The rain it raineth every day;

From May again until July,

There's not a dry cloud in the sky;

All the rest have thirty-one,

Without a blessed ray of sun;

And if any of them had two-and-thirty,

They'd be just as wet and quite as dirty."

Also,

" If I could stretch from pole to pole,

And grasp its icy span,

Although this is but a dirty hole,

'Tis better than dry scan."

"Dry scran," I was informed, meant dry bread. Amongst my campanions were a tailor, aged 67, decently dressed, a compositor, also respectably attired, and a band-maker, while the remainder could scarcely be classified, except as labourers. Several of them had worked in the town on previous occasions, and on explaining myself as a native of Keighley, I was led into conversations which were remarkably interesting. Breakfast was brought in by a pauper attendant, and consisted of seven pieces of dry bread on a board, each piece weighing 8oz., one for beach vagrant. These wore placed upon the stone floor, while in a surly tone the man who brought them exclaimed,

"THEAR'S YER TOMMY."

Talk about the haughty pomposity of parish beadles! It was nothing in, comparison with the attitude of the pauper as he deposited Our breakfasts upon the ground. A rusty can was then brought in, containing about two quarts of cold water, which was to serve as a drink for all of us. A strong feeling of indignation rose within me as I observed the Miserable fare, and the contemptuous manner in which it was served out. Although I was told I should need it before the day was finished, I gave my share away, whilst the others seized upon their portions eagerly and devoured them with apparent relish, more than one, though, complaining that in England vagrants were treated worse than criminals were in any other country. After a sufficient time had been allowed for breakfast, we were ordered out to

PERFORM OUR TASK WORK.

Two were relegated to some lighter labour, whilst five, amongst whom was myself, were set to corn-grinding. We were placed in a room, consisting of but two narrow passages at right angles. Here protruding, from the wall were six wheels with handles attached, and nothing else but the dead wall was discernible. After being ordered to grind away at these, we were locked in. Some of the machines were dreadfully hard to turn, whilst others were not so bad. Fortunately mine was one of the latter, and I was very much envied by the others, when they observed how easily my wheel went round. One of the vagrants, who had been at the game before, had made the calculation that to grind the requisite four bushels of corn, it was necessary to make 8,800 turns at the wheel. He adopted the process of counting the revolutions, and every time he reached 100 he made a note of it on the wall with a pencil, and then rested himself on the wheel handle before commencing the next century. The old tailor performed his work very methodically, if rather slowly; but all were agreed they would not kill themselves with the job. The "comp," who performed next to me, was very weak, and could scarcely work his machine. The most aggravating part of the affair was that none of us could observe how much work had been accomplished.

THE ATMOSPHERE WAS VERY WARM,

And in midsummer must have been nearly stifling. Being in want of something to drink, we thrust a tin through an aperture in the window, with a request to one of the paupers to fill it with water. The tin was taken away, but no water appeared, and nearly an hour elapsed before our wants were supplied in this respect, and then only because of repeated knocks and shoutings. Drearily the hours passed until twelve o'clock, when we were liberated for dinner, consisting of thick soup, which I could not bring myself to taste. From one to five o'clock corn-grinding was again our portion; after which the night was spent much similar to the last one. I was greatly pleased: when my time expired and I was again a free man. I quickly travelled down Oakworth Road, and immediately on reaching home cast off cast off my tramp's garb for ordinary attire.

MY IMPRESSION

Of the general treatment of vagrants is that the system is much too severe. Making every allowance for the shortcomings of the class constituting them, I am of opinion that the lowest of mankind deserve better treatment than that accorded to pigs, dogs, and other animals of creation. The food furnished was scarcely fit for these last mentioned, whilst about the harsh treatment the less said the better. It is a disgrace to, any civilised country. The only redeeming feature I observed was the general cleanliness of the place. Where, I noticed anything dirty it arose from the habits of the vagrants themselves. I would not again for a substantial sum, be placed in a similar position, if I had any choice in the matter, nor shall I forget for a long time to come, my experience in the Vagrants' Ward of the Keighley Union as an "Amateur Casual."

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.