The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act

In the wake of the 1832 Royal Commission's report on the operation of the poor laws, its recommendations were put into effect throughe the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 — An Act for the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England and Wales (4 & 5 Will IV c. 76) which received Royal Assent on August 14th, 1834.

You can read the full text of the 1834 Act

Title page of the 1834 Poor Law Act

© Peter Higginbotham.

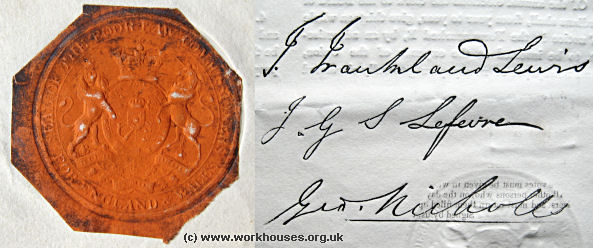

The 1834 Act was largely concerned with setting up the legal and administrative framework for the new poor relief system. At its heart was the new Poor Law Commission which was given responsibility for the detailed policy and administration of the new regime. Three Poor Law Commissioners were appointed (George Nicholls, John Shaw-Lefevre and Thomas Frankland Lewis) with Edwin Chadwick as their Secretary. The Commission was based at Somerset House in London.

The seal and signatures of the Poor Law Commissioners.

© Peter Higginbotham.

One of the Commission's first tasks was to set about dividing the 15,000 or so parishes of England and Wales into new administrative units called Poor Law Unions each run by a locally elected Board of Guardians. (Local Act Incorporations and Gilbert Unions were exempted from the new scheme, something that was to irritate the Commission and its successors for many years.) The funding of each Union and its workhouse continued to come from the local poor rate with each parish contributing in proportion to its poor relief expenditure over the previous three years. Following the principle established by the 1818 Sturges Bourne Act, ratepayers were given votes (up to six) in proportion to the value of their property.

The creation on the new unions was undertaken by a team of Assistant Commissioners visiting each area and conducting meetings with local parish officials and landowners. In some areas, landowners with large estates were able to achieve considerable influence over the groupings of parishes forming each union. Landowners generally preferred to keep their estates within a single union which would allow them the maximum of influence on its Board of Guardians. The new Potterspury union in Northamptonshire, for example, ended up with only eleven member parishes, eight of which were owned entirely or in part by the Duke of Grafton.

The overall working and implementation of the new system was put into practice by means of a large volume of orders and regulations issued by the Commission which specified every aspect of the operation of a Union and its workhouse. The Commission had the power to issue 'General Orders' which would apply to a number of unions, and 'Special Orders' which were specific to one. General Orders required parliamentary approval, while Special Orders did not. The Commission got around this restriction by repeatedly issuing identical 'special' orders to multiple individual unions. It was not until 1841 that the first General Orders were submitted for parliamentary approval. Many of the previous special orders were subsequently revised and reissued an general orders culminating in the issue in 1847 of the Consolidated General Order which became the 'bible' of the system's operation.

.Bibliography

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531-1782, 1990, CUP.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law History, 1927, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

- Webb, Sidney and Beatrice English Poor Law Policy, 1910, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

Unless otherwise indicated, this page () is copyright Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.